|

The image above presents a ‘before treatment’ (left) and ‘after treatment’ (right) brain scan image from a recent research report of a clinical study that looked at the use of Acetylcysteine (also known as N-acetylcysteine or simply NAC) in Parkinson’s disease. DaTscan brain imaging technique allows us to look at the level of dopamine processing in an individual’s brain. Red areas representing a lot; blue areas – not so much. The image above represents a rather remarkable result and it certainly grabbed our attention here at the SoPD HQ (I have never seen anything like it!). In today’s post, we will review the science behind this NAC and discuss what is happening with ongoing clinical trials. |

Source: The Register

Let me ask you a personal question:

Have you ever overdosed on Paracetamol?

Regardless of your answer to that question, one of the main treatments for Paracetamol overdose is administration of a drug called ‘Acetylcysteine’.

Why are you telling me this?

Because acetylcysteine is currently being assessed as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

Oh I see. Tell me more. What is acetylcysteine?

Acetylcysteine. Source: Wikimedia

Acetylcysteine. Source: Wikimedia

Acetylcysteine (N-acetylcysteine or NAC – commercially named Mucomyst) is a prodrug – that is a compound that undergoes a transformation when ingested by the body and then begins exhibiting pharmacological effects. Acetylcysteine serves as a prodrug to a protein called L-cysteine, and – just as L-dopa is an intermediate in the production of dopamine – L-cysteine is an intermediate in the production of another protein called glutathione.

Take home message: Acetylcysteine allows for increased production of Glutathione.

What is glutathione?

Glutathione. Source: Wikipedia

Glutathione (pronounced “gloota-thigh-own”) is a tripeptide (a string of three amino acids connected by peptide bonds) containing the amino acids glycine, glutamic acid, and cysteine. It is produced naturally in nearly all cells. In the brain, glutathione is concentrated in the helper cells (called astrocytes) and also in the branches of neurons, but not in the actual cell body of the neuron.

It functions as a potent antioxidant.

We have previously discussed antioxidants (click here to read that post). An antioxidant is simply a molecule that prevents the oxidation of other molecules. Which begs the question:

What is oxidation?

Oxidation is the loss of electrons from a molecule, which in turn destabilises the molecule. Think of iron rusting. Rust is the oxidation of iron – in the presence of oxygen and water, iron molecules will lose electrons over time. Given enough time, this results in the complete break down of objects made of iron.

Rusting iron. Source: Thoughtco

The exact same thing happens in biology. Molecules in your body go through a similar process of oxidation – losing electrons and becoming unstable. This chemical reaction leads to the production of what we call free radicals, which can then go on to damage cells.

What is a free radical?

A free radical is an unstable molecule – unstable because they are missing electrons. They react quickly with other molecules, trying to capture the needed electron to re-gain stability. Free radicals will literally attack the nearest stable molecule, stealing an electron. This leads to the “attacked” molecule becoming a free radical itself, and thus a chain reaction is started. Inside a living cell this can cause terrible damage, ultimately killing the cell.

Antioxidants are thus the good guys in this situation. They are molecules that neutralize free radicals by donating one of their own electrons. The antioxidant don’t become free radicals by donating an electron because by their very nature they are stable with or without that extra electron.

How free radicals and antioxidants work. Source: h2miraclewater

When the brain is affected by free radicals or any other toxic agent, astrocytes can release their store of glutathione into the space outside of neurons to help defend those them from any attack, and glutathione within the branches of the neurons deals with anything that actually manages to enter the cell.

Thus, glutathione plays an important in removing free radicals.

Do we know anything about glutathione with regards to Parkinson’s disease?

Yes we do.

First, glutathione appears to be reduced in many important areas of the Parkinsonian brain:

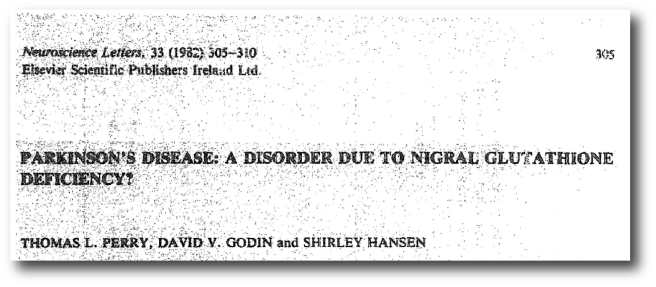

Title: Parkinson’s disease: a disorder due to nigral glutathione deficiency?

Authors: Perry TL, Godin DV, Hansen S.

Journal: Neurosci Lett. 1982 Dec 13;33(3):305-10.

PMID: 7162692

The investigator who conducted this study began by analysing levels of glutathione in autopsied human brain. They found that in general glutathione content is significantly lower in the substantia nigra (the region where the dopamine neurons live) than in other brain regions. But when they looked at glutathione levels in the substantia nigra of people who died with Parkinson’s disease, they barely detected any glutathione at all.

This result has been subsequently repeated by several other independent groups (Click here, here and here to see some of those reports). The initial discovery, though, led the investigators to excitedly question whether the Parkinson’s disease was partly the result of a glutathione deficiency.

Unfortunately for those excited investigators, glutathione deficiency is not specific to Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Nigral glutathione deficiency is not specific for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Fitzmaurice PS, Ang L, Guttman M, Rajput AH, Furukawa Y, Kish SJ.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2003 Sep;18(9):969-76.

PMID: 14502663

In this study, the researchers found that decreased levels of glutathione in the substantia nigra is a common feature across several neurodegenerative conditions, including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

Interestingly they also saw a trend towards decreased levels of uric acid (another antioxidant that we have previously discussed – Click here to read that post) in the substantia nigra of all the neurodegenerative groups analysed (a decrease of -19 to -30%). In addition, previous reports have indicated that glutathione levels in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease are significantly reduced (click here for more on this). Thus, reduced levels of glutathione appears to be a common feature of neurodegenerative conditions.

Researchers have subsequently found that decreased levels of glutathione does not directly result in dopamine cell loss (Click here to read more about this), but it does make the cells more vulnerable to damaging agents (such as neurotoxins, etc – Click here and here to read more about this). This has lead investigators to ask whether administering glutathione to people with Parkinson’s disease would slow done the condition.

Has glutathione ever been tested in clinical studies for Parkinson’s disease?

Yes it has. At least four times in fact!

Title: Reduced intravenous glutathione in the treatment of early Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Sechi G, Deledda MG, Bua G, Satta WM, Deiana GA, Pes GM, Rosati G.

Journal: Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1996 Oct;20(7):1159-70.

PMID: 8938817

In the first clinical trial to test glutathione in Parkinson’s disease, the investigators recruited nine people with recently diagnosed (and untreated) Parkinson’s disease. Glutathione was administered intravenous twice per day (600 mg each time) for 30 days. The drug was then discontinued and the participants were followed up for 4 months.

All of the participants in this study improved significantly after glutathione treatment (an average of 42% decline in disability) and the beneficial effects lasted for 2-4 months after the treatment was stopped at the end of the study. Particularly, interesting was the change in resting tremor intensity:

Intensity of the resting tremor of a subject with PD at baseline (A), after 30 day of glutathione treatment (B), 60 days after stopping glutathione treatment (C), and 30 days after returning to L-dopa (D). Source: Sciencedirect

Following this study, a series of videos were placed online which caused a lot of excitement within the Parkinson’s community:

A second video demonstrated some beneficial effects in three other people with Parkinson’s disease:

One cautionary note regarding the first glutathione study and these subsequent videos, however, is that in all of these cases, the investigators and the subjects were not blind – they all knew who was getting the treatment and what the treatment was. Thus, investigator bias and the placebo effect could have been at work.

To deal with this possibility a randomised, double blind clinical study was organised by Dr David Perlmutter (one of the investigators who first posted the videos online):

Title: Randomized, double-blind, pilot evaluation of intravenous glutathione in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Hauser RA, Lyons KE, McClain T, Carter S, Perlmutter D.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2009 May 15;24(7):979-83.

PMID: 19230029

The investigators of this study randomly assigned 20 subjects with Parkinson’s disease to receive intravenous glutathione (1,400 mg) or a placebo treatment (10 people in each group). Both were administered three times a week for 4 weeks. The investigators found that glutathione was well tolerated and there were no withdrawals due to any adverse events of the treatment.

Importantly, there were no significant differences in changes in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores. The UPDRS is a universally utilised method of scoring the severity of Parkinson’s disease features/symptoms. Over the 4 weeks of study, the glutathione group exhibited only a mild improvement when compared to the control. That trend did continue, however, over a subsequent 8 week follow up period, which saw the control group worsened by an average of 3.5 points more than the glutathione-treated group. The researchers concluded by suggesting that further evaluation was required in a larger, longer study.

Intravenous delivery of glutathione is not an ideal treatment approach for a community that has movement issues, and this was taken into consideration when the next clinical trial of glutathione was conducted:

Title: A randomized, double-blind phase I/IIa study of intranasal glutathione in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Mischley LK, Leverenz JB, Lau RC, Polissar NL, Neradilek MB, Samii A, Standish LJ.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2015 Oct;30(12):1696-701. doi: 10.1002/mds.26351. Epub 2015 Jul 31.

PMID: 26230671 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers utilised a nasal spray approach to get glutathione into the body. The goal of the study was to test the safety and tolerability of intranasal delivery of glutathione in people with Parkinson’s disease. The investigators recruited 30 individuals with Parkinson’s disease, who were randomly assigned to either a placebo/control group (saline) or to a treatment group (two doses were tested on the treatment group – 300 mg/day or 600 mg/day of intranasal glutathione). The study was conducted over 3 months and found little difference between the groups with regards to the clinical features of Parkinson’s disease, but did find that intranasal glutathione was well tolerated by all of those involved in the study.

This first trial has subsequently led to a phase II study to look more carefully at the effectiveness of intranasal delivery of glutathione.

Title: Phase IIb Study of Intranasal Glutathione in Parkinson’s Disease

Authors: Mischley LK, Lau RC, Shankland EG, Wilbur TK, Padowski JM.

Journal: J Parkinsons Dis. 2017 Apr 20. doi: 10.3233/JPD-161040.

PMID: 28436395 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

Curiously in this double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, all of the 45 individuals (averaging 3.5 years since diagnosis) involved in the study improved during the study (including the control group), suggesting that there was some kind of placebo effect at play within the cohort. The subjects were divided into three groups: a control group, a low dose treatment group, and a high dose treatment group for the intranasal glutathione treatment.

The high-dose group demonstrated improvement in total UPDRS score over their baseline scores, but neither treatment group improved more than the placebo control group (who also improved). It was therefore difficult for the researchers to conclude that glutathione is superior to placebo after a three month intervention (although obviously there may have been a placebo effect occurring in the control).

So glutathione treatment doesn’t work?

I would not interpret the results that way.

Firstly, none of these clinical studies have recruited enough participants for major conclusions to be made of their results, except that collectively they indicate that glutathione appears to be safe for use in folks with Parkinson’s disease.

In addition, they have all been rather short studies (conducted over a matter of weeks or months) which makes determining changes in UPDRS scores or simply disease progression rather difficult. Parkinson’s is a slow progressive condition. Therapies that slow or halt the disease require longer periods to demonstrate efficacy.

Are there any clinical trials being conducted at the moment for glutathione in Parkinson’s disease?

There have been quite a few clinical trials involving glutathione, but currently there is only one that is recruiting, and that study is only a brain imaging study that will be investigating glutathione levels using magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging, to determine if quantitative measures can be made. The hope is that glutathione can be used as a biomarker – allowing for measurements of disease progression.

So there are no clinical trials for glutathione at the moment?

Not that I’m aware of (and happy to be corrected on this). And this is a shame. It would be good to have a proper, large, double-blind clinical trial to evaluate the potential of glutathione, ideally over 6-12 months.

There are, however, other ongoing clinical studies that are investigating drugs that indirectly influence this glutathione pathway:

Edison Pharmaceuticals is a biotech company taking a drug (EPI-589) to the clinic for Parkinson’s disease. EPI-589 (also known as Troloxamide quinone) is a redox (meaning reduction–oxidation reaction) active molecule, that has significant effects on increasing glutathione levels.

Exactly what EPI-589 does is a bit of a mystery (there is very little preclinical data available regarding it – even on the company’s own website). It is described online as an “NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone) modulator” (which basically translates to: an antioxidant.

In this phase IIa clinical trial, investigators are recruiting 40 individuals who have recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s (and are currently not being treated with any drugs such as L-dopa), and they are also recruiting subjects with genetic forms of Parkinson’s (such as mutations in genes such as PARKIN, PINK, and LRRK2).

The trial will run for 5 months and all of the participants will be taking the drug EPI-589 (it will be an open-label study – Click here for more information regarding this trial). You can also find more information on the CureParkinson’s Trust website.

Ok, and what about the clinical study of NAC in Parkinson’s disease you mentioned at the start of the post?

Ah yes. I almost forgot.

So in addition to treating paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose (as discussed above), acetylcysteine is also used to loosen up thick mucus in conditions such as cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It can be taken intravenously, by mouth (in pill form), or inhaled as a mist.

One of the big issues with using glutathione as a treatment is that glutathione can not be taken up by neurons. It is generally made inside the cell. NAC, on the other hand is readily taken up by neurons and it can help to boost neuronal GSH levels. NAC has been shown to be neuroprotective in animal models of Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more on this), which has led researchers to investigate its use as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease:

Title: N-Acetyl Cysteine May Support Dopamine Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease: Preliminary Clinical and Cell Line Data.

Authors: Monti DA, Zabrecky G, Kremens D, Liang TW, Wintering NA, Cai J, Wei X, Bazzan AJ, Zhong L, Bowen B, Intenzo CM, Iacovitti L, Newberg AB.

Journal: PLoS One. 2016 Jun 16;11(6):e0157602.

PMID: 27309537 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers in this study began their investigation by looking at the effect of NAC on the survival of dopamine neurons (made from human embryonic stem cells) in culture after exposure to a neurotoxin (rotenone; which is a pesticide/insecticide that has been associated with Parkinson’s disease – click here to read more on this).

They found that NAC treatment resulted in significantly more dopamine neurons surviving the exposure to rotenone when compared to cultures that received no NAC. Armed with this result, the investigators boldly moved straight into the clinic and started a clinical study (click here for the details of that trial). They took 23 people with Parkinson’s disease (average time since diagnosis was approx. 3 years) and randomly assigned them to either the NAC group (12 subjects) or the control group (11 subjects). The study was not blinded, so both the investigators and the participants knew which treatment they were being administered. And the NAC was administered intravenously and orally.

At the start of the study, all of the subjects were assessed using the UPDRS scoring system and imaging of the brain was conducted using DaTscan. During the study, both groups continued their normal treatment for their Parkinson’s symptoms, with the experimental group also receiving NAC (50mg/kg) once per week. After approximately 90 days of NAC treatment, all of the subjects underwent a follow up evaluation, which included another UPDRS assessment and DaTscan brain image.

After the study, the UPDRS score of the NAC treated group dropped from an average of 25.6 to 22.3, while the control group increased from 20.2 to 22.2. The UPDRS has a list of 55 items that are graded 0-4 depending on level of severity. A lower score indicates a more normal level of activity. Thus, any decrease in UPDRS score can be seen as a positive outcome – in this case the treated group improved by 12.9% on average.

Importantly, the brain imaging also showed a significantly increase in DAT binding in the caudate and putamen in the brain. The investigators wrote that the increase ranged from 4.4% to 7.8%….

…which does bring into question the image at the top of this post….

That would be this image here:

Now,…. call me me crazy, but the increase in the level of red between the left (before NAC treatment) and right (after NAC treatment) brain scans strikes me as sliiiightly more than an 8% increase! No?

Either way, the investigators saw beneficial effects from using NAC in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Yes, the study was not blinded, but it is intriguing that the benefits were observed in brain imaging assessments as well as clinical scores – it is harder to suggest any placebo effect is occurring when brain imaging suggests improvements.

Two clinical trials following up these results. One study is being conducted at Thomas Jefferson University by the researchers who conducted the study reviewed above. This study is recruiting participants by invitation only – click here to read more about this. The second study is being conducted by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (Click here for more information about this).

Is this the first time NAC has been tested in people with Parkinson’s disease?

Actually, no.

In one previous clinical study, intravenously administered NAC was shown to boost brain glutathione concentrations in people with Parkinson’s disease (Click here and here to read more on this study).

Wow, this sounds good. Where can I get me some of this NAC stuff?

NAC is widely available as a dietary supplement.

But… there is just one slight problem with it: NAC is poorly absorbed when taken orally. Only about 6–10% of it passes through to the blood stream, and this can vary between individuals (Click here and here to read more on this).

But NAC is an interesting molecule that warrants further research. Some investigators have suggested that NAC may have a direct role in neuroprotection as a scavenger of oxygen radicals by itself (Click here for more on this). And it has been shown to be a modulator of the immune system and mitochondrial processing (Click here and here for more on this).

Thus I think it deserves more attention.

What does it all mean?

A recent clinical study has suggested some positive benefits to using acetylcysteine (or NAC) – a supplement that stimulates the production of an antioxidant called glutathione. This study and other previous clinical studies investigating glutathione production, indicate that NAC is worthy of further investigation (both in the lab and the clinic).

For those folks who are interested in learning more about NAC, you should definitely read a recent post on Prof Frank Church’s blog Journey with Parkinson’s.

Hope you liked it Don.

ADDENDUM:

This additional section has been added following a question asked by a reader in the comments section below. The question was:

“If PD patients ONLY take the NAC pills (no intravenous, due to the problems associated with intravenous administration), and 1) only 6-10% of oral NAC makes it to the blood stream, and 2) the experiment did not specifically test for oral only NAC;

we do not know if NAC pill only patients would that see the same positive results?

your thoughts?”

It’s a good question, addressing an issue I basically avoided in the post to save space (the post was getting long and unwieldy). Plus, I’m not sure that we really know the answer.

A couple of years ago this research report was published:

Title: Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of N-acetylcysteine after oral administration in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Katz M, Won SJ, Park Y, Orr A, Jones DP, Swanson RA, Glass GA.

Journal: Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015 May;21(5):500-3.

PMID: 25765302 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators recruited 12 people with Parkinson’s disease and gave them oral NAC twice daily for 2 days. Three different doses of NAC were compared (7 mg/kg, 35 mg/kg, and 70 mg/kg), and cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid that your brain sits in) was collected before the start of the study and then again at 90 min after the last dose of NAC, to analyse levels of NAC reaching the brain and the amount of glutathione subsequently produced.

The results showed that the lowest dose (7mg/kg) had little effect, but the highest dose (70mg/kg) significantly increased NAC levels in the cerebrospinal fluid. This means that NAC is getting into the brain after oral treatment. One issue arising from this study however, was that this increase in NAC levels had little/no effect on the levels of glutathione circulating in the spinal fluid (see image below).

No change in glutathione (GSH) levels. Source: rxlist

No change in glutathione (GSH) levels. Source: rxlist

Now, this lack of glutathione increase could simply be due to the short time frame of the study (just 2 days). Or it could be that glutathione is principally produced and housed inside neurons and helper cells (like astrocytes) in the brain, and not much of it is floating around for investigators to detect.

What was really missing from this study was an analysis of some actual brain tissue, and it would appear that the participants were not too willing to have samples taken (understandable I guess).

Luckily for us, these same scientists followed up that first study and published a report recently about a study addressing exactly how much NAC in cerebrospinal fluid was required to affect glutathione levels in neurons:

Title: Neuronal Glutathione Content and Antioxidant Capacity can be Normalized In Situ by N-acetyl Cysteine Concentrations Attained in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid.

Authors: Reyes RC, Cittolin-Santos GF, Kim JE, Won SJ, Brennan-Minnella AM, Katz M, Glass GA, Swanson RA.

Journal: Neurotherapeutics. 2016 Jan;13(1):217-25.

PMID: 26572666 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, healthy mice were treated with NAC over a range of doses, and then the researchers measured neuronal glutathione levels and neuronal antioxidant capacity in pieces of brain tissue. Glutathione levels (and the antioxidant capacity) was augmented by NAC at doses that produced peak cerebrospinal fluid NAC concentrations of ≥50 nM. This is far below the 10mM levels achieved using 70mg/kg of NAC in the first study, suggesting that “oral NAC administration can surpass the levels required for biological activity in brain”. In other words, not much oral NAC is required for beneficial levels to be achieved.

Re-reading through this now, I guess this last section would have rounded off the post quite nicely and maybe I should have added it (Blame my poor judgement on limited ability and writing this stuff in the wee small hours). But one important question remains: does this last finding in the mice apply in a situation like Parkinson’s disease where there is already a reduction in glutathione levels in the brain? (see top of the post) Further research is required looking that NAC and Parkinson’s disease.

So my answer is we simply don’t know.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Under absolutely no circumstances should anyone reading this material consider it medical advice. The material provided here is for educational purposes only. Before considering or attempting any change in your treatment regime, PLEASE consult with your doctor or neurologist. While some of the drugs discussed on this website are clinically available, they may have serious side effects. We therefore urge caution and professional consultation before any attempt to alter a treatment regime. SoPD can not be held responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided here.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from PLOSONE

Yes I liked it. I am sure your other hundred plus and growing readers liked it too. What a hook and then accurate thorough info. Where can I get me some nasal NAC spray – or even the placebo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I felt my comment above didn’t do justice. Graphs, videos, multicolored brains, very clear and readable and seems very important. A+

LikeLike

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – these SoPD posts are brilliant. They make complex studies very clear and simple for the general reader, and the style is excellent. I honestly look forward to receiving SoPD posts – please keep up the good work Simon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Ken,

Thanks for the comment, especially given the flattering words. Pleased you liked the post, it was a long time in preparation this one!

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I agree wholeheartedly with the comments already made – Simon is a master at getting to grips with technical data and deciphering it for ordinary mortals to read and understand. It was a lucky day for me when I was introduced to his blog by a friend.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Lionel,

Thanks for the comment and the kind words – much appreciated. Glad you liked the post. Have a good weekend,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon, Great post, as usual.

My understanding of the results of the NAC clinical trial is that it showed positive results for PD.

But unfortunately, since the NAC was given both intravenously and orally to the same patients -> we do not know if it was the intravenous NAC and/or the oral NAC that impacted the results?

Thus, if PD patients ONLY take the NAC pills (no intravenous, due to the problems associated with intravenous administration), and

1) only 6-10% of oral NAC makes it to the blood stream, and

2) the experiment did not specifically test for oral only NAC;

we do not know if NAC pill only patients would that see the same positive results?

your thoughts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi KJJ,

Thanks for your comment and interesting question. Yes, the water is a bit murky given the strange combo treatment in the study. I have added an addendum to the bottom of the post trying to address this issue. There is no clear answer to the question, but I hope this helps.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Hi! New to your marvellous site! As a researcher/writer and carer for Parkinson’s, it may be of some help to know my PD-hubby’s history with IV glutathione pushes. DX in 2001, he had a two-year course of this, followed by a a course from a PhD in Philly that claimed she could cure anything from PD, ALS, severe Autrism etc. with her Phosphatidylcholine plus Glutathione IVs. We did this 2- 3 years into his dx. 17 years later; his progression remains ‘on track’.

Like with so much else, there is validity in you post – actually you’re gonna be my BFF! But, the merit due here may be down to the application of intranasal introduction, although it has been said to increase the chance of cancer.

The bid problem is ‘translation’ through the BBB, which simply defies entry without morphing.

In my thoughts, like brain-tissues transplants, therein lies the rub: one has to cross that infernal barrier that only let VIRUS in…curious.

Love your concepts and research – keep it up!

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

Thanks for your comment and information provided. Very interesting. Sorry to hear that your husband didn’t respond to NAC treatment. I agree that it is very curious how viruses manage to cross the blood-brain-barrier and I am looking to investigate this in the lab in the not so distant future.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Please excuse me but I am confused by your reply. Why did you say there was a lack of response by her husband to NAC treatment? It seemed as though her husband was given glutathione treatments, correct? I realize that NAC can be a precursor to glutathione but the dynamics of production and activity of various compounds in vivo seems to be impacted by factors governed by dynamic equilibrium as well as biological activity. That is to say in many other instances the body maintains particular levels of compounds by using enzymes and other factors that shift their activity according to levels of these compounds in the body at any given time. This typically allows the body to adjust levels according to demand and conclusion of demand for compounds. Clearly, it is only a guess, but the impact of higher amounts of glutathione per se, could possibly influence other enzymatic or biological activities when given systemically that might not be the same as raising the intracellular level of glutathione by increasing levels of NAC. Is this not possible, or did the treatment Lisa referred to entail something I am not understanding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Simon, it is great that you are willing to spend time answering questions from “the general public”. A friend of mine has PD and asked me to help him understand the scientific literature since at one time I did research in the biosciences. Question: a visit to clinicaltrials.gov revealed 2 NAC trials targeting Parkinson’s Disease where Primary Data Collection (PDC) was completed but study results were not yet posted: NCT01470027 (PDC apparently completed Aug 2016) and NCT02212678 (PDC apparently completed Sept 2015). Why does it take so long to post the results? What is a reasonable delay? At what point. If any, should one suspect the data was discouraging? I also used Safari on my iPad to “google” these trials but found no publication of results. (If I copied the trial numbers incorrectly the following will help ID the trials: NCT01470027 done by Weill Medical College Cornell Univ. NCT02212678 by Univ. of Minnesota. Thanks! Allan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Allan,

Thanks for your comment. Sorry to hear about your friend, but you effort to help them is admirable. The issue of delayed/no clinical trial results has been a major topic of discussion recently within the research community (see: http://www.bmj.com/content/352/bmj.i637 – 44% of clinical trials have not been published up to seven years after study completion!). The World Health Organisation has made a lot of noise about this issue (http://www.alltrials.net/news/who-calls-for-all-clinical-trial-results-to-be-published/). As for why the delay exists, some of these large studies (think 300+ people enrolled) will require a lot of time to collect and analyse the results from multiple research centres. And then after the study report has been written up, it has to go through the peer-review process which can easily take 6 months of back-and-further communications between reviewers and investigators. And yes, all the while the affected community is waiting. This is the system we have created.

As for why some results are never published, there could be many reasons not necessarily discouraging (eg. drug company has a bad result and is shut down. Ex-employees can not be bothered publishing the results, which also has a cost attached $1-2K).

There are certainly efforts being made to repair this situation. Of particular interest is the All Trials effort (http://www.alltrials.net/). In addition, if there is a particular trial you are interested in you can always find the Principal Investigator on the clinicaltrials.gov webpage and email them to find out what happened.

I hope this helps.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLiked by 1 person

It appears that the NAC clinical trial (NCT01470027) has posted results and my reading of the results are that NAC tablets do not raise glutathione levels any more than placebo. And it also appears that while UPDRS scores improved somewhat – they also improved no more than placebo. So basically the NAC tablets did nothing. Is my data interpretation correct?

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01470027?term=nac&cond=parkinson%27s&rank=1§=X01256#all

LikeLike

KJJ_me: If I’m reading the posted results correctly, it fully supports the benefits of NAC for Parkinson’s. Ignoring the glutathione numbers for a moment, just look at the UPDRS values. In just four weeks at 1800mg of NAC per day, they changed from a baseline of 35.286 to a reduced value of 23.857. That is a reduction of over 32 percent!

It seems that the reduction of UPDRS for 3600mg per day was less – from 31.5 to 24.249, which is a 23 percent reduction. One might infer from this that 1800mg per day is closer to an ideal dosing level.

The placebo effect, by contrast, is 17.1 percent. So, there’s almost twice the effect when taking 1800mg per day. The placebo group seems to have gotten a healthier group at baseline, presumably because of the random selection…? Not sure what the significance of that is, but there certainly does appear to be a much greater effect than placebo, when dosing is at a good level.

I’m not sure why you thought that the results were no better than placebo; have I perhaps mis-read the data myself?

LikeLike

KJJ_me: In addition, the study *does* seem to show that, since glutathione levels did *not* change appreciably, that the *benefits* the study shows as being conferred by NAC treatment on UPDRS did not *depend* upon the NAC treatment increasing glutathione levels.

LikeLike

Thanks for linking to the alltrials site; first I had heard of it. Seems like an excellent initiative, and much needed.

LikeLike

Simon,

I appreciated the detailed response to my questions about the delay in reporting clinical trials.

Your article starts with the striking DaTscan images of a patient before and after NAC treatment. Later, when discussing the Monti et al. article that reported the image, you expressed (well-justified) disbelief that the image could be explained by an 8 % increase in the color level. Eight percent being the maximum increase that the text of the article would lead one to expect. Looking into the article further, I think I can see the gap between the image and the text.

Towards the end of the article (which, I could access on the internet) there is a section, “Supporting Information”. If one goes there and clicks on “S1 Dataset”, you find DaTscan and UPDRS data on each of the 23 patients in the study. Patient 2 had the most striking DaTscan results: Rcaud was 1.64 before NAC treatment and 2.62 after NAC treatment. That is a 60% increase. For Lcaud, the increase was about 53%. And if all 4 regions are considered, the average increase as 36 percent. Numbers like that did not make it into the text of the article. What the upper limit of an 8% increase means is still unclear, but it certainly does not refer to the upper limit of what was observed.

The above numbers would be only slightly changed if the control patient values were taken into account.

Looking at the S1 DataSet, and comparing the DaTscan values with the UPDRS values, it is also interesting because it gives a clearer idea of why it would be hard to use changes in DaTscan values to predict changes in the UPDRS values.

Allan

LikeLike

Good observation Allan – thanks for sharing! That clears things up a bit.

Much appreciated.

Simon

LikeLike

Regarding delayed posting of clinical trial data, that phenomenon cost us some serious money about a decade ago.

Back in 2007, there was a University of South Florida study of IV glutathione in which Dr. David Perlmutter was involved, that ultimately showed its complete lack of efficacy for PD. It was co-sponsored by a supplements company named Wellness.

The study started in September of 2003 and was completed in March of 2007. But results have not been posted on the clinical trial site even now, in 2018. Here is the clinical trials page for that study:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01177319

There was, however, a study report, which was published over two years after study completion, in 2009. Here is that published study. It shows that the glutathione cohorts improved for a short time, then declined much faster than controls, and ended up slightly worse than the placebo group.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/19230029/

In the interval between study completion and learning the results of the study, my partner and I had purchased a number of bottles of an expensive liposomal glutathione product from the company that co-sponsored the study (Wellness), which we would never have purchased had the study results been promptly available. That study was known to us, and we were actively looking for results from that study during the time that we were using this product.

In response to our repeated inquiries, Wellness said that they were also anxious to see the study results, and followed up with those involved with the study to obtain them. A sympathetic employee there copied me on their request, and on the response to it from a member of the study team, in April of 2008:

From the request by Wellness for the data to members of the study team:

“Several times I have requested the data from the glutathione study on

Parkinson’s, and have not received a response. I understand from a

brief conversation with ____, that the results were less than

favorable. Nevertheless, please send me a copy of all applicable

results and statistical analysis, so that we can review them. After

we do so we may want to discuss the situation to see if there should

be another study.”

And, from the reply to that request:

“In the initial data set there was not a statistically significant

change in favor of glutathione…”

Although, in our case as least, Wellness did sell some additional product as a result of this delay, it is not clear that they had anything to do with the delay in releasing the study’s results. Some of those on the study team had been outspoken in promoting the benefits of IV glutathione for PD, and so might also have had a motive for sitting on the study results. And, then again, it may have been simply slow processing of results, which appears in this case to have benefited a number of parties connected with the study in various ways, although perhaps that benefit was not the cause of the delay.

I have no way of knowing what the reasons for the slow posting were, but I have searched in vain for any sign of anyone involved with it stating “well, I guess we made a mistake in promoting IV glutathione for Parkinson’s…”

LikeLike

Thanks Allan – good insight.

I have a dumber but more practical question that maybe people can weigh in on. If one is already taking 2 grams of resveratrol each day and 4 grams / day of olive leaf, should one also be taking grams of NAC and turmeric? Uncharted territory I think.

Maybe go by the side effects if any? There is a complimentary medicine doc I could go see – but insurance doesn’t cover him. Not sure he would know either. My MDS Doc says “I have no idea”

Thanks for any advice

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dkdc,

I have to admit that I also fall into the “I have no idea” basket on this one.

For these sorts of questions, I usually refer folks to Dr Laurie Mischley – a nutritional guru who co-ordinated several of the Glutothione/NAC clinical study mentioned above. She will probably be best placed to answer your question ( http://bastyr.edu/people/alumni-researcher/laurie-mischley-nd-mph-phdc).

I hope this helps.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

dkdc: The problem with most clinical trials is that they are typically for monotherapies. It’s understandable, because you want to isolate the effects of a particular substance, but it’s also probably the case that a multi-pronged approach will ultimately turn out to be most effective for PD. Even if a substance fails to show benefit as a monotherapy, it might still have benefits when combined with other approaches.

So, while we can’t entirely *reject* a substance based on its failure as a monotherapy, when a substance *does* turn out to have clear benefits as a monotherapy in a trial, that provides some definite basis for interest. For example, ubiquinol and NAC both have trials that indicate benefit for PD as monotherapies, so for me, at least, those two will be “keepers.”

Now, regarding your question, my personal belief is that Parkinson’s progression occurs in large part due to an autoimmune feedback loop, and so you want to interfere with that loop in as many ways as possible, to reduce its effects, and ideally to stop it altogether. NAC is an antioxidant, and as such, probably interferes with the cascade of processes involved in apoptosis (cell death) of neurons, which is one part of the autoimmune loop. Turmeric contains curcumin, which has the capacity to block receptors on microglia that would otherwise be triggered by alpha synuclein and neuromelanin from damaged neurons, causing those microglia to attack and injure non-damaged “bystander” neurons in the process.

So, both substances could be helpful, in different ways, and so it seems reasonable to me that you might do both at once. Although, instead of turmeric, you might consider the Longvida brand of curcumin, which stays active in the body much longer, and reaches higher levels, than mere turmeric can.

As for olive leaf, I’m not aware of any proven PD benefits for that, unless you happen to have a candida overgrowth in your gut that is driving autoimmune activity generally, which could affect autommune activity in the brain. Because olive leaf can be used as part of a treatment plan to help get rid of candida. But I’m not aware of anything that it does specifically for PD.

However, if you suspect olive leaf extract might possibly have some benefit, then the question to ask would be whether it might work compatibly with other substances you are using, and whether it might affect the autoimmune feedback loop in ways that those other substances do not (so that it is not doing the same thing redundantly). And, of course, first and foremost, whether it has a proven safety record.

LikeLike

Hi Simon

In your blog on broccoli you reference Dr Rhonda Patrick and one of her videos. Check out the one on cryotherapy. She says “You know all that liposomal gluthione you’ve been dosing well it will do nothing without the enzyme to make it work” or something like that. So she is suggesting combining with cryotherapy/cold water immersion to get some kind of enhanced antioxidant effect. Any thoughts?

Chris

LikeLike

It seems oral glutathione may in fact work? One of the researchers mentioned above recommends it. Here is more info – not sure of what quality, https://www.clinicaleducation.org/resources/reviews/oral-glutathione-equivalent-to-iv-therapy/

acetyl glutathione only

LikeLike

I found the NAC NINDS study here: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Clinical-Trials/Does-N-Acetylcysteine-NAC-Produce-Anti-Oxidant-Effect-Parkinson’s-Disease

LikeLike

Simon, I love your blog, and in general this article contains a lot of important information, but I fear you may have made an error regarding one important fact reported by the University of South Florida study.

Your article states that:

“Over the 4 weeks of study, the glutathione group exhibited only a mild improvement when compared to the control. That trend did continue, however, over a subsequent 8 week follow up period, which saw the control group worsened by an average of 3.5 points more than the glutathione-treated group.”

However, the study abstract actually says that:

“Over the 4 weeks of study medication administration, UPDRS ADL + motor scores improved by a mean of 2.8 units more in the glutathione group (P = 0.32), and over the subsequent 8 weeks worsened by a mean of 3.5 units more in the glutathione group (P = 0.54).”

So, the study seems to be saying that while the glutathione group did better than the control group for the first four weeks, that effect was temporary, and was more than *reversed* over the subsequent 8 weeks, so that, at the end of the 12 weeks, the glutathione group was actually slightly worse off than the control group.

LikeLike

I would add to the above comment that the pattern shown in the University of South Florida study, of improvement for four weeks, followed by regression back to (or below) the level of the placebo group, might possibly explain why the videos shared by Dr. Perlmutter seemed so encouraging. In the *short run*, there was improvement, but it was not lasting improvement, and ultimately amounted to zero or negative improvement.

Also, the 1996 study that you cite lasted for only 30 days (just over four weeks), and so it may be that the initial benefits shown for tremor by that point were due to this same temporary effect (of approximately four weeks’ duration). If there were in fact longer term improvements, then it seems *possible* that *stopping* the glutathione therapy after one month was the key to that more lasting success. If so, then perhaps a pulsatile therapy of one month one, three months off, would attain better results…? Of course, that’s all highly speculative, but it shows that there are other possible interpretations of their results. In other words, it may not be valid to extrapolate that benefits would continue if glutathione treatments were controls after the first four weeks.

If this four week duration of benefit turns out to be a real thing, then it would certainly be interesting to investigate the mechanism of action that might lead to such a result. But in the meantime, we have NAC, which now two studies say does benefit PD, and according to the most recent of the two, *without* raising glutathione levels in the process. Here is the clinical trial data (linked by KJJ_me above, although I think his reading of it was incorrect). I haven’t seen an actual article about this study thus far:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01470027?view=results

LikeLike

One thing I’m a little confused about is whether the measured changes in glutathione in NAC clinical trial results such as this one:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01470027?term=nac&cond=parkinson%27s&rank=1§=X01256&view=results#all

in any way reflect the effects of the NAC’s *reducing* glutathione by donating electrons to it.

The study linked above (which appears to have posted its data very recently) shows significant benefits of NAC for UPDRS, but almost no change in glutathione levels as a result of NAC supplementation.

It seems possible to me that NAC, as an electron donor, could be *reducing* oxidized glutathione back to a reduced state in the brain, from which state the GSH can again function as an antioxidant. Perhaps that is occurring without the measured *amount* of glutathione changing very much? And perhaps that is in part responsible for the UPDRS benefits, while not changing the measured levels of glutathione?

My understanding is that NAC is capable of performing that kind of “recharging” service via a number of antioxidants – not just glutathione, but also for vitamin C and others. So, given that NAC can cross the blood-brain barrier, perhaps it is getting into the brain and then reviving/recharging the antioxidant capacities of glutathione, vitamin C, etc., some of which (glutathione in particular) may not readily cross the blood-brain barrier themselves.

That could explain why there is no convincing evidence of glutathione supplementation benefiting PD, but there is good evidence that NAC provides such benefits. Glutathione may still play a role in transferring antioxidant capacity from NAC to other molecules within the brain, and yet not work as an exogenous supplement because of an inability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Does any of that make sense to you?

LikeLike

To correct my own comment above: as the article states, glutathione *can* cross the blood-brain barrier. So the issue is really glutathione’s inability to pass through the neuronal cell membrane, while NAC *can* pass into the cytoplasm of neurons.

LikeLike

It’s been years now since this article was written, but I just wanted to add that I suspect that glutathione deficiency is probably not a *cause* of Parkinson’s, but is rather one of its effects.

Specifically, the cytokines released by microglia in their attacks upon neurons act upon neurons through oxidative processing, which could consume endogenous glutathione, rendering it in short supply.

So adding NAC, by increasing glutathione within neurons, allows the further quelling of the oxidative processes incited by the cytokines that are part of the autoimmune feedback loop that drives PD.

LikeLike

Hi Simon, can you comment on the study results from this topic below

https://healthunlocked.com/cure-parkinsons/posts/148793751/epi-589-ptc-589-r-troloxamide-quinone-phase-2-study-results-2022

LikeLike

Hi Hnedim,

Thanks for the interesting question. I haven’t seen any results beyond what is posted on the clinicaltrials.gov website, so it is difficult to say much. This was a Phase 2A trial assessed the safety of EPI-589 in 40 individuals with “mitochondrial subtype” PD (they carry a PARKIN or PINK1 genetic variant) or idiopathic PD. EPI-589 is an agent that helps to improve mitochondrial function in cells. Think: powerful anti-oxidant. It was open-label & involved all of the 40 participants taking the drug for 30 days with many biomarkers (in blood, CSF, & urine) being assessed. And the primary endpoint (the main measure of this short study) was safety & tolerability. It was too small & short for any really measure of clinical efficacy. Of the 41 participants in the study, 29 experienced an adverse event. None were considered as serious and most only affected 1 or 2 individuals which raises the question of whether they were drug specific or related to something else. The most common were nausea (in 7 cases) and headache (8 cases), both of which usually appear in most studies. So the drug looks pretty safe. As I said above, the study was too small & short for any measures of clinical efficacy. A much larger & longer properly statistically powered study is required for that. The results of this study have not been published in a journal & it is not clear from the results presented on the clinicaltrials.gov website (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/history/NCT02462603?V_16=View#StudyPageTop) what the plans for EPI-589 are. As far as I know only 1 study has been published on this agent (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35988057/). The biotech firm that was developing the drug (Edison Pharmaceuticals Inc; aka BioElectron Technology Corporation) has been purchased by a larger company PTC Therapeutics, & EPI-589 does not appear on their pipeline (https://ptcbio.com/our-pipeline/portfolio-pipeline/), but a related agent does: EPI-743. We’ll have to wait & see what the company does next with EPI-589. A manuscript on EPI-589 provides some encouraging preclinical data (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.03.13.484182v1.full).

I hope this helps,

Simon

LikeLike