|

People with high socioeconomic status jobs are believed to be better off in life. New research published last week by the Centre for Disease Control, however, suggests that this may not be the case with regards to one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. In today’s post we will review the research and discuss what it means for our understanding of Parkinson’s disease. |

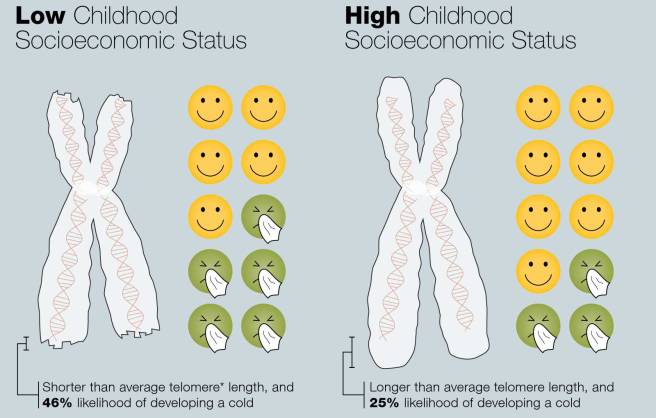

The impact of socioeconomic status. Source: Medicalxpress

In 2013, a group of researchers at Carnegie Mellon University found a rather astonishing but very interesting association:

Children from lower socioeconomic status have shorter telomeres as adults.

Strange, right?

Yeah, wow, strange… sorry, but what are telomeres?

Do you remember how all of your DNA is wound up tightly into 23 pairs of chromosomes? Well, telomeres are at the very ends of each of those chromosomes. They are literally the cap on each end. The name is derived from the Greek words ‘telos‘ meaning “end”, and ‘merοs‘ meaning “part”.

Telomeres are regions of repetitive nucleotide sequences (think the As, Gs, Ts, & Cs that make up your DNA) at each end of a chromosome. Their purpose seems to involve protecting the end of each chromosome from deteriorating or fusing with neighbouring chromosomes. Researchers also use their length is a marker of ageing because every time a cell divides, the telomeres on each chromosome gradually get shorter.

Telomeres. Source: Telomereinformation

Ok, so poor kids have shorter telomeres. So what?

Well, having shorter telomeres is associated with the early onset of illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and cancer (Click here to read more about this). But the Carnegie Mellon researchers noticed something else:

Having shorter telomeres predicts one’s susceptibility to infectious disease in adulthood

In other words, they found that low socioeconomic status during childhood increased one’s susceptibility to the common cold.

Here is the research report:

Title: Childhood socioeconomic status, telomere length, and susceptibility to upper respiratory infection.

Authors: Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB, Marsland AL, Casselbrant ML, Li-Korotky HS, Epel ES, Doyle WJ.

Journal: Brain Behav Immun. 2013 Nov;34:31-8.

PMID: 23845919 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The investigators measured the telomere lengths of white blood cells from 152 healthy individuals (aged of 18 and 55). As a measure of their childhood and current socioeconomic status, the participants were asked whether they currently own their house and whether their parents owned the family home that they grew up in (between the age of 1 to 18 years).

The investigators next exposed the participants to a rhinovirus – which causes a common cold – and they then waited five days to see if the participant went on to develop an infection (I would really love to know how this project proposal passed the ethics board).

Source: NCBI

The results showed that participants from lower childhood socioeconomic status had both shorter than average telomere length (see graph above) and were more likely to become infected by the cold virus. In fact, for each year that their parents did not own a home during their childhood, the participants’ odds of developing a cold increased by 9 percent. This report was a replication and extension on this research group’s previous findings that had a very similar result (Click here to see that previous report)

Wow. That actually is really interesting. Are telomere lengths shorter in Parkinson’s disease?

No, shorter telomere length is not associated with Parkinson’s disease. A recent study showed that “there is no consistent evidence of shorter telomeres” in people with Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more about this).

Ok, so why are you telling me about telomeres and socioeconomic status?

Because last week the Centre for Disease Control published the results of a study that suggested that socioeconomic status may actually influence one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease).

But rather than being associated with a low socioeconomic status, the report found a positive association between high socioeconomic status jobs and both Parkinson’s disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

Here is the report:

Title: Mortality from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Parkinson’s Disease Among Different Occupation Groups – United States, 1985-2011.

Authors: Beard JD, Steege AL, Ju J, Lu J, Luckhaupt SE, Schubauer-Berigan MK.

Journal: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Jul 14;66(27):718-722.

PMID: 28704346 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers used data from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) database called the National Occupational Mortality Surveillance (NOMS). NOMS is a US-based program that monitors work-related acute and chronic disease mortality among workers in 30 U.S. states. The database contains information associated with approximately 12.1 million deaths.

In total, there were 26,917 deaths associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and 115,262 deaths associated with Parkinson’s disease. The occupations of the deceased were then grouped into 26 categories based on similarities of job duties and ordered roughly from high socioeconomic status (e.g., legal, finance, management) to lower socioeconomic roles (e.g., construction, transportation and material moving).

After accounting for age, sex, and race, the investigators found that occupations associated with higher socioeconomic status particularly elevated in people that died with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

There is a bit of devil in the detail about this study though…

For Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 14 occupations were significantly associated with the disease and 4 categories were particularly strong in their association (computer and mathematical; architecture and engineering; legal; and education, training, and library).

In the Parkinson’s disease analysis, 13 occupation categories were significantly associated with the condition. These included:

- Education, training, and library

- Community and social services

- Legal

- Life, physical, and social sciences (Eeek!)

- Computer and mathematical

But (unlike, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) none of the occupations were particularly high in their association with Parkinson’s (Click here to see the full list). So the occupation risk effect appears to be stronger for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

And curiously, the occupation category of ‘Farming, fishing, and forestry’ did not have a strong association with Parkinson’s disease, which is strange given the strong association between farming and Parkinson’s in past studies (Click here for more on this). The researchers acknowledged this, but could not explain the difference with previous studies.

Also curious, 11 occupation categories were significantly not associated with Parkinson’s disease. These included:

- Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance

- Protective service

- Food preparation and serving

- Transportation and material moving

- Installation, maintenance, and repair

And one in particular – called ‘extraction‘ [involving mining or oil and gas drilling] – was particularly not associated with Parkinson’s disease. I now know what I’ll be encouraging my daughter to do for a living.

Has this occupation/socioeconomic thing ever been investigated before?

Yes, a few times. One recent example is:

Title: Occupational complexity and risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Valdés EG, Andel R, Sieurin J, Feldman AL, Edwards JD, Långström N, Gatz M, Wirdefeldt K.

Journal: PLoS One. 2014 Sep 8;9(9):e106676.

PMID: 25198429 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators used the Swedish Twin Registry that included 28,778 twins (born between 1886 and 1950). They identified 433 cases of Parkinson’s disease. When they assessed occupations, they found that high occupational complexity (with data and people) was associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, particularly in men.

And there are previous research reports supporting the idea of more complex occupations being associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s (Click here and here to see two examples).

Has this kind of analysis ever been done for other types of neurodegenerative conditions, like Alzheimer’s disease?

Yes, and strangely with regards to Alzheimer’s disease, the data suggests the opposite effect:

Title: Relation of education and occupation-based socioeconomic status to incident Alzheimer’s disease.

Authors: Karp A, Kåreholt I, Qiu C, Bellander T, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L.

Journal: Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Jan 15;159(2):175-83.

PMID: 14718220

In this study, the investigators recruited a group of 931 non-demented people (aged older that 75 years) from the Kungsholmen Project in Stockholm (Sweden). They followed these subjects for 3 years (between 1987 and 1993). A total of 101 incident cases of dementia were detected during this time. Interestingly, the results suggested that subjects with less formal education were almost 3.5 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than those with more education. In addition, subjects with a lower socioeconomic status were 1.6 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

So the high socioeconomic status effect is specific to Parkinson’s and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

Well, maybe for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, but I am not so convinced with the Parkinson’s disease data. There could be another way of interpreting the data. The highest categories of association (in order) for Parkinson’s disease were:

- Education, training, and library

- Community and social services

- Legal

- Life, physical, and social sciences (Eeek again!)

- Computer and mathematical

Call me crazy, but there could be a theme here. For example, all of these jobs require attention to detail. And they all require an element of commitment/endeavour about them. Perhaps all of these jobs would be best conducted by people with specific personality traits.

What are you suggesting?

In 1913, Dr Carl Camp, a neurologist at the University of Michigan, wrote in ‘Modern Treatment of Nervous and Mental Diseases’:

“It would seem that paralysis agitans (the old name for Parkinson’s) affected mostly those persons whose lives had been devoted to hard work… The people who take their work to bed with them and who never come under the inhibiting influences of tobacco or alcohol are the kind that are most frequently affected. In this respect, the disease may be almost regarded as a badge of respectable endeavor”

Cited from Menza M. (2000).

Dr Carl Camp. Source: OldNews

Dr Carl Camp. Source: OldNews

This was the first time anyone had proposed that certain personality traits may be associated with Parkinson’s disease. And since Dr Camp’s comment, over 100 years ago now, a lot of studies have been conducted on this topic and many of them agree that certain personality traits that are associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. These traits include:

- Industriousness

- Punctuality

- Inflexibility

- Cautiousness

- Lack of novelty seeking

And the evidence suggests that these traits persist long after the onset of the illness – that is to say, they are not affected by the disease. I have previously written about the idea of a Parkinson’s personality (Click here to read that post).

The question has to be asked: do people at risk of developing Parkinson’s disease gravitate towards the sort of occupations that are described in the CDC study as ‘high socioeconomic status’? In other words, are the high socioeconomic status jobs simply favourable to the Parkinson’s personality traits?

So rather than being a warning about high socioeconomic status jobs, is the CDC report merely further evidence supporting the idea of a ‘Parkinson’s disease personality type’?

I don’t have the answer. I just thought that this was an alternative way of looking at the results.

What does it all mean?

Recently a group of researchers at the Centre for Disease Control in the USA published an interesting report about occupation and risk of developing either Parkinson’s disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Their results found that people in high socioeconomic status jobs had a higher risk of developing the two diseases.

While this effect is more prominent in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, I personally think that the interpretation could be incorrect in the case of Parkinson’s disease. Rather than providing a public health warning to anyone seeking to enter the ‘high socioeconomic status jobs’, the findings of the study may simply be pointing towards the personality traits that have been previously associated with Parkinson’s disease.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from the Huffington Post

Interesting – PD = a badge of honor. “These traits include: Industriousness Punctuality Inflexibility Cautiousness Lack of novelty seeking”

Perhaps someone will have a relevant question – I have one that is mostly not related – I have heard that people with PD are more prone to the placebo effect than others. True? Is it cause we mess around with dopamine – the feel good neurotransmitter?

“The Science Behind the Placebo Effect

It is important to note that the placebo effect is not a figment of the participant’s imagination. There are biochemical changes occurring in the brain. We think the placebo effect may be so prominent in Parkinson’s clinical trials because of the neurotransmitter called dopamine — the same neurotransmitter that is reduced

or lost in Parkinson’s. It turns out that dopamine also underlies the placebo effect. When a person is motivated to participate in a trial and anticipates a possible reward — for example, the easing of symptoms — these all boost dopamine activation in the brain.”

http://www.pdf.org/summer12_placebo

Maybe this will tempt Simon into another post

thanks

LikeLike

Maybe Simon has already posted about the placebo effect.

LikeLike

Indeed he has: https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2016/01/03/the-placebo-effect-and-parkinsons-disease/

But it needs to be re-addressed. I think this is one of the big problems we have in the PD research world. Clinical trials may be failing because the placebo effect is so rife in PD. I have a few other pots on the boil at the moment, but I will be coming back to the placebo effect soon.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Excellent again. Extremely interesting especially since the previous post was about Helicobacter pylori which is more associated with developing countries………..

I am in agreement with dkdc (?Don) that more on the placebo effect would be welcome.

Simon I love the way that you bring all avenues of research to the table, personality, environment, physical effects etc. This gives so much greater understanding of the complexity of this disease but does give me brainache. Thank you for presenting it all in a palatable manner. Look forward to the next post.

LikeLike

Sorry I didn’t check before posting. The placebo post was pretty good -Don

LikeLike

Hi Hilary,

Thanks for the comment – glad you liked the post. And I will get started on that placebo post ASAP.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

So this is exactly the kind of data i am looking for. Our work with flies suggests that the PD mimics do “better” than the controls. The nervous systems of the mimics respond faster and more strongly than the controls, suggesting they have more neural processing capacity. Thus, we predicted that, in young life, people who later developed PD would be more neurally capable (“more intelligent?, able to escape difficult situations, able to react faster) and have an advantage.

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

Thanks for the really interesting comment. It raises a bunch of fascinating possibilities. I recently gave a talk to some folks with young-onset PD and an interesting comment made to me in the Q&A session was that they generally felt they were all of better than average intelligence. And, all joking about such a comment aside, perhaps there could be something to it (there could also be a sampling bias – those proactive enough to go to such a support group – but we’ll ignore that for the moment). It got me thinking though: most of the genetically engineered mice that have been generated for the various genetic variants associated with PD have been thoroughly assessed for any motor deficit (and largely been found wanting), but I wonder how many of them have been placed in a operant chamber or equivalent learning test? It could be interesting to assess the general intelligence levels of those mice. Intriguing thought.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Yes, i don’t think the mice people have really looked hard at the ‘prodromal’ phase; there are a few pointers though: (Longo, Russo, Shimshek, Greggio, & Morari, 2014; Matikainen-Ankney et al., 2016; Ponzo et al., 2017; Sloan et al., 2016)

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

Thanks for the suggested papers. While it’s great that two of these papers are open access – the Longo paper (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4194318/) and Sloan paper (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4754049/) – it is disappointing that only one of them actually did anything cognitive (and that was just a T-maze!). It could be interesting to reach out to the Wade-Martin group in Oxford and ask if they are following up their rats with some more cognitive tests.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

For ‘mice’ read ‘rodent’ as some of the papers are with rats – can you edit the comment please

LikeLike