|

The title of today’s post is written in jest – my job as a researcher scientist is to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease…which will ultimately make my job redundant! But all joking aside, today was a REALLY good day for the Parkinson’s community. Last night (3rd August) at 23:30, a research report outlining the results of the Exenatide Phase II clinical trial for Parkinson’s disease was published on the Lancet website. And the results of the study are good:while the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease subject taking the placebo drug proceeded to get worse over the study, the Exenatide treated individuals did not. The study represents an important step forward for Parkinson’s disease research. In today’s post we will discuss what Exenatide is, what the results of the trial actually say, and where things go from here. |

Last night, the results of the Phase II clinical trial of Exenatide in Parkinson’s disease were published on the Lancet website. In the study, 62 people with Parkinson’s disease (average time since diagnosis was approximately 6 years) were randomly assigned to one of two groups, Exenatide or placebo (32 and 30 people, respectively). The participants were given their treatment once per week for 48 weeks (in addition to their usual medication) and then followed for another 12-weeks without Exenatide (or placebo) in what is called a ‘washout period’. Neither the participants nor the researchers knew who was receiving which treatment.

At the trial was completed (60 weeks post baseline), the off-medication motor scores (as measured by MDS-UPDRS) had improved by 1·0 points in the Exenatide group and worsened by 2·1 points in the placebo group, providing a statistically significant result (p=0·0318). As you can see in the graph below, placebo group increased their UPDRS motor score over time (indicating a worsening of motor symptoms), while Exenatide group (the blue bar) demonstrated improvements (or a lowering of motor score).

Reduction in motor scores in Exenatide group. Source: Lancet

This is a tremendous result for Prof Thomas Foltynie and his team at University College London Institute of Neurology, and for the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research who funded the trial. Not only do the results lay down the foundations for a novel range of future treatments for Parkinson’s disease, but they also validate the repurposing of clinically available drug for this condition.

In this post we will review what we know thus far. And to do that, let’s start at the very beginning with the obvious question:

So what is Exenatide?

In 2012, the Golden Goose Award was awarded to Dr John Eng, an endocrinologist from the Bronx VA Hospital.

Dr John Eng. Source: Health.USnews

The Award was created in 2012 to celebrate researchers whose seemingly odd or obscure federally funded research turned out to have a significant and positive impact on society. And despite the name, it is a very serious award – past Nobel prize winners (such as Roger Tsien, David H. Hubel, and Torsten N. Wiesel) are among the awardees.

What did Dr Eng do?

In the 1980’s, Dr Eng became really interested in some studies (such as this one) that described the effects of certain types of venom had on cells in the pancreas. The pancreas is the organ that produces the chemical insulin which is critical for maintaining normal glucose levels in our bodies. Having worked with diabetic people who do not produce enough insulin, Dr Eng started wondering if venom may contain chemicals that could help people with diabetes. But rather than injecting diabetic people with venom, he started looking at all the chemicals that make up the venom from different poisonous creatures.

Venom looks like great fun. Source: Cen

What did he find?

This delightful creature is a Gila monster.

The Gila monster. Source: Californiaherps

Cute huh?

Named after the Gila River Basin of New Mexico and Arizona (where these lizards are found and protected by State law), these venomous, but sluggish creatures spend 95 percent of their time underground in burrows.

In 1992, Dr Eng identified the two proteins that he had isolated from the venom of the Gila monster. One of them was called exendin-4 and it bore a striking similarity -structurally and functionally – to a human protein, called glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1).

What is GLP-1?

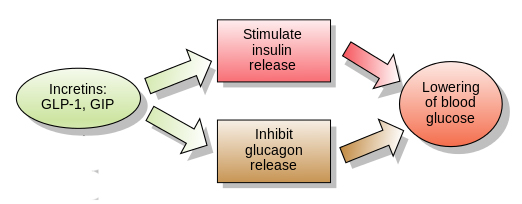

Insulin instructs cells to take in and use glucose from the blood. This has the effect of lowering blood sugar. The hormone Glucagon has the opposite effect – it tells the body to release glucose into the blood to raise sugar levels. GLP-1 is a hormone that stimulates insulin production while blocking glucagon release.

The function of GLP-1. Source: Wikipedia

Unfortunately, naturally produced GLP-1 in your body is rapidly deactivated by a circulating enzyme called dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Exendin-4, however, was found to be resistant to this deactivation, meaning that could last longer in the body stimulating insulin production and blocking glucagon release. Dr Eng quickly realised that there was enormous medicinal potential for exendin-4 as a drug for people with diabetes. He patented the idea and soon afterwards a biotech company called Amylin Pharmaceuticals to begin the work of turning exendin-4 into a drug for diabetes.

That drug was eventually called Exenatide.

In April 2005, Byetta (the commercial name for Exenatide) was approved by the FDA for clinical use in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. On the 27th January 2012, the FDA gave approval for a new formulation of Exenatide called Bydureon, as the first weekly treatment for Type 2 diabetes. In July of 2012, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced it would acquire Amylin Pharmaceuticals for $5.3 billion, and one year later AstraZeneca purchased the Bristol-Myers Squibb share of the diabetes joint venture.

So Exenatide or Exendin-4 has been tested in models of Parkinson’s disease?

A lot of preclinical research was conducted on Exendin-4 before Exenatide was taken to the clinic. It all started with this study published in 2008:

Title: Peptide hormone exendin-4 stimulates subventricular zone neurogenesis in the adult rodent brain and induces recovery in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Bertilsson G, Patrone C, Zachrisson O, Andersson A, Dannaeus K, Heidrich J, Kortesmaa J, Mercer A, Nielsen E, Rönnholm H, Wikström L.

Journal: J Neurosci Res. 2008 Feb 1;86(2):326-38.

PMID: 17803225

In this study, Exendin-4 was tested in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Five weeks after giving the neurotoxin (6-hydroxydopamine) to the rats, the investigators began treating the animals with exendin-4 over a 3 week period. Despite the delay in starting the treatment, the researchers found behavioural improvements and a reduction in the number of dying dopamine neurons.

And this first result was followed a couple of months later by a similar report with a very similar set of results:

Title: Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor stimulation reverses key deficits in distinct rodent models of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Harkavyi A, Abuirmeileh A, Lever R, Kingsbury AE, Biggs CS, Whitton PS.

Journal: J Neuroinflammation. 2008 May 21;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-19.

PMID: 18492290 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The scientists in this study tested exendin-4 on two different rodent models of Parkinson’s disease (6-hydroxydopamine and lipopolysaccaride), and they found similar results to the previous study. The drug was given 1 week after the animals developed the motor features, but the investigators still reported positive effects on both motor performance and the survival of dopamine neurons.

And the following year, in 2009, two more research reports were published suggesting that exendin-4 was having positive effects in models of Parkinson’s disease (Click here and here to read those reports). This was a lot of positive results for this little protein.

How is Exendin-4/Exenatide having this positive effect?

Exendin-4 is a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

What does that mean?

In cells, receptors act as switches for certain biological processes to be initiated. Receptors will wait for a protein to come along and activate them or alternatively block them. The activators are called agonists, while the blockers are antagonists.

Agonist vs antagonist. Source: Psychonautwiki

Exendin-4 and Exenatide are agonists, so they activate the GLP-1 receptor.

Activation of the GLP-1 receptor by a GLP-1 receptor agonist like Exendin-4 or Exenatide results in the activation of many different biological pathways within a cell:

The GLP-1 signalling pathway. Source: Sciencedirect

Of particular importance is that GLP-1 receptor activation inhibits cell death pathways, reduces inflammation, reduces oxidative stress, and increases neurotransmitter release. All pretty positive stuff really. For a recent and very good OPEN ACCESS review of the GLP-1-related Parkinson’s disease research field, click here.

And all of these research reports led to and supported the idea of clinically testing Exenatide in people with Parkinson’s disease.

What happened in the first clinical trial?

The first clinical trial of Exenatide in Parkinson’s disease was a phase I trial to determine if the drug was safe to use in people with Parkinson’s disease. The results of the trial were published in 2013:

Title: Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Aviles-Olmos I, Dickson J, Kefalopoulou Z, Djamshidian A, Ell P, Soderlund T, Whitton P, Wyse R, Isaacs T, Lees A, Limousin P, Foltynie T.

Journal: J Clin Invest. 2013 Jun;123(6):2730-6.

PMID: 23728174 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers gave Exenatide (the Byetta formulation) to a group of 21 people with moderate Parkinson’s disease and evaluated their progress over a 14 month period. They compared those participants to 24 additional subjects with Parkinson’s disease who acted as control (they received no treatment). Exenatide was well tolerated by the participants, although there was some weight loss reported amongst many of the subjects (one subject could not complete the study due to weight loss).

Importantly, the Exenatide-treated subjects demonstrated improvements in their Parkinson’s disease movement symptoms (as measured by the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (or MDS-UPDRS)), while the control patients continued to decline.

Interestingly, in a two year follow up study – which was conducted 12 months after the subjects stopped receiving Exenatide – the researchers found that participants previously exposed to Exenatide demonstrated a significant improvement (based on a blind assessment) in their motor features when compared to the control subjects involved in the study.

It is important to remember, however, that this trial was an open-label study – that is to say, the participants knew that they were receiving the Exenatide treatment so there is the possibility of a placebo effect explaining the improvements. And this necessitated the testing of the efficacy of Exenatide in a phase II double blind clinical trial.

And it is the results of that trial that were published in this report last night:

Title: Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

Authors: Athauda D, Maclagan K, Skene SS, Bajwa-Joseph M, Letchford D, Chowdhury K, Hibbert S, Budnik N, Zampedri L, Dickson J, Li Y, Aviles-Olmos I, Warner TT, Limousin P, Lees AJ, Greig NH, Tebbs S, Foltynie T

Journal: Lancet 2017 Aug 3. pii: S0140-6736(17)31585-4.

PMID: 28781108

In the study, the investigators recruited 62 people with Parkinson’s disease (average time since diagnosis was approximately 6 years) and they randomly assigned them to one of two groups, Exenatide (the Bydureon formulation) or placebo (32 and 30 people, respectively). One of the interesting aspects of this study is that the participants were given their treatment just once per week (as opposed to twice per day in the phase I clinical trial – though that was a different formulation of Exenatide) and this was enough to see a positive result. The treatment was given for 48 weeks (in addition to their usual medication) and then the participants were followed for another 12-weeks without Exenatide (or placebo) in a ‘washout period’.

It is important to remember that in this trial everyone was blind. Both the investigators and the participants. This is referred to as a double-blind clinical trial and is considered the gold standard for testing the efficacy of a new drug.

As I mentioned at the top of this post, the researchers found a statistically significant difference in the motor scores of the Exenatide group verses the placebo grouo (p=0·0318). As the placebo group continued to have an increasing (worsening) motor score over time, the Exenatide group demonstrated improvements, which remarkably remained after the treatment had been stopped for 3 months.

Reduction in motor scores in Exenatide group. Source: Lancet

Brain imaging (DaTscan) also suggested a reduced rate of decline in the Exenatide group when compared with the placebo group. Interestingly, the researchers found no significant differences between the Exenatide and placebo groups in scores of cognitive ability or depression – suggesting that the positive effect of Exenatide may be specific to the dopamine or motor regions of the brain. Claire Bale (Head of Research Communications & Engagement) at Parkinson’s UK has written a very good report on the study and in that write up she questions whether enough Exenatide was actually reaching the brain in this current study, when compared to the phase I trial. In the phase I trial, Exenatide improved performance on both movement and cognitive tests, so why the difference in this study?

Similar to the phase one study, there was some weight loss in the Exenatide group. At 48 weeks, the Exenatide group had lost an average of 2·6 kg, while the control group had lost only 0·6 kg. This reduction in weight may need to well monitored if GLP-1 agonists are to be considered a treatment option for Parkinson’s disease in the future.

While the results are very exciting, the researchers note that they also raise a lot of questions, such as “Whether Exenatide affects the underlying pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease or simply induces long-lasting symptomatic effects remains uncertain”.

They concluded the report by writing that the “results represent a major new avenue for investigation in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.”

What happens now?

That’s the question on everyones lips.

The investigators discussed this in their report. They start by suggesting that longer follow up trials will be necessary to determine the consequences of long-term use of Exenatide treatment on daytime function in Parkinson’s disease. Particularly they are curious to see whether Exenatide displays any delaying of the development of Levodopa-induced complications (such as dyskinesias).

They also asked the question ‘if Exenatide works for Parkinson’s, then why not other neurodegenerative disorders (such as, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis) or other neurological diseases (including cerebrovascular disorders, traumatic brain injury).

These are interesting questions, but the elephant in the room is the owner of Exenatide. As I mentioned above, Exenatide is controlled by the pharmaceutical company Astrazeneca.

And this drug is heavily protected patent-wise (there are one hundred and forty-three patent family members in twenty-one different countries for Exenatide! Three of these patents expire this year, four more in 2018 and 2020). Astrazeneca (who kindly provide the drugs used in this current trial) will have control over where things go from here with regards to Exenatide.

And then there is also this patent which deals with the use of different versions of GLP-1 and exendin-4 in neurodegenerative conditions.

Curiously this patent belongs entirely to the US Government.

One of the investigators in the Exenatide clinical trial research report we have reviewed in this post is Dr Nigel H Greig of the NIH Translational Gerontology Branch of the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore. Dr Greig is a named inventor on the patent describing the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in neurodegenerative disorders. All rights to this patent belong solely to the US Government.

So I guess… that Mr Trump gets a say in what happens next?

Moving on before we get too political, there are ways of getting around such a patent.

Rather than simply using GLP-1 receptor agonists, there are alternative methods to achieving the same goal. For example, orally administered drugs have recently been developed that block the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase IV from deactivating GLP-1. This class of drugs allow naturally occurring levels of GLP-1 to rise (as much as twofold). These drugs are currently used in the treatment of diabetes and some of them have demonstrated beneficial neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more about this).

So what does it all mean?

It means that Dr Eng is probably on his way to winning another Golden goose award! Not only has he provided a treatment for diabetes, but perhaps also one for neurodegenerative conditions.

This phase II trial result indicating that the diabetes drug Exenatide can have beneficial effects on Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms is very exciting. And there will be a lot of temptation for many in the Parkinson’s disease community to get excited and demand Exenatide from their doctors. But caution must be taken as we move forward, as there is still a lot we do not know. For example, as the investigators themselves admit, we do not know the long term consequences of using this drug in the context of Parkinson’s disease. Or how often the drug can be used (once per week may be beneficial, but daily could be toxic). We simply do not know yet.

I can not help but feel happy and excited by this result though. It represents so many positive things:

- Validation that we are heading in the right direction.

- Proof that the idea of repurposing drugs for this condition will work.

- Motivation to continue the work that is still to be done in other areas.

Tonight I’ll certainly toast Dr Eng, Prof Tom Foltynie and his team, and everyone at the MJFF.

(Not to forget the Cure Parkinson’s trust to helped fund the early Exenatide clinical work – Tom would have been very please with this result).

And my apologies for the dramatics, but I often think the best analogy of Parkinson’s disease is that of a war. And up until 60 years ago, we were losing that war – no doubt about it. Then we established a small beach landing in the bay of Levodopa, and since then we have never looked back. Yes, there have been casualties (in the last 18 months we have lost of two of our most prominent generals) and there have been many failures (think Cogane or Neurturin). But importantly there has always been progress: that little beach landing 60 years ago has now opened up, creating a war on many, many fronts, and new weapons are being added to the arsenal at an ever increasing rate.

The news last night alerted us to the fact that a small victory has been gained – a break in the enemy’s line if you will. One that we are now going to fully exploit, at the same time as we also seek victories elsewhere. As I said at the post of this post, today is a REALLY good day for the Parkinson’s community.

And in keeping with the war, I’ll finish with Sir Winston Churchill who said it best:

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts”.

EDITORIAL NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. Please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Diatribe

Perhaps an ignorant question – it seems the effects over a year are small. Certainly everyone will be happy with getting slowly better rather than worse. I suppose give it five years of maybe daily doses and we could have an even more dramatic effect?

Simon reporting from the front….

LikeLike

Hi Don,

Not an ignorant question. It’s actually a very good one. As Claire Bale from Parkinson’s UK suggested in her blog post about this study (https://medium.com/parkinsons-uk/exenatide-latest-trial-results-explained-ef72fbee3c44), one of the differences between this current study and the first (phase I) clinical trial is a change in the formulation and administration of Exenatide. In the first study, Exenatide was given twice per day (20micrograms), while in this study it was only given once per week (2milligrams). It may be that not enough drug was getting to the brain in order to see a bigger effect in this current study. It is difficult to say though, and we are simply speculating here. A bunch of follow up trials will address this, but the important message from this first double-blind trial is that there was an effect! And if in the long run all Exenatide does is slow down the condition, it still represents a major step forward in the war effort.

Currently under heavy fire, please send in air support,

Simon

LikeLike

Hi Richard,

Thanks for your message. It is all currently in the public domain on the website. Please let me know if you want the contents edited to a shorter statement regarding Tom, or if you are happy for it to all be public I can leave it.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Hi Richard,

Thanks for the comment. I replied earlier, but was not sure if you received the response due to poor coverage where I currently am. By sending your comment via the comment section of the website, it was immediately placed in the public domain. I have removed it for now in case you didn’t want any of the contents of the comment to be public. I will wait for your response before making it public again.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

It is interesting that those on Exenatide appeared to improve over the first 12 weeks and then plateaued. I hope that future research will closely monitor different doses over the first 3 months. I think there is also a need to undertake more accurate and consistent measurements to quantify changes in motor symptoms.

LikeLike

Hi Jim,

It is an interesting observation that you have made. The trial results do not allow us to determine if the effect is neuroprotective or simply addressing symptoms (particularly as the motor features are the only responsive component of the analysis – no between group differences in cognition for example). It would be curious to replicate the follow up study of the phase I study where they retested all of the subjects 12 months after the trial and found the Exenatide group were still better off. Carefully design follow up experiments will soon be underway looking at all of this. It is amazing, however, that this effect is possible with just one treatment per week.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I noticed that same phenomenon; the decline vs. control that was present at the very first reading after starting treatment was still responsible for the entire difference between the exenatide group and the control group, even at the end of 60 weeks. So, the clock was set back on a one-time basis for the illness, but then progression continued as usual.

It seems almost as if the dopamine neurons that were still alive started performing more optimally when exenatide treatment created more favorable conditions for them, but continued nonetheless to decline and die after that point, and at about the same rate as before.

To me, that suggests that maybe the factors ameliorated by exenatide were causing sub-optimal neuronal performance, but that some other factor that was *not* affected by exenatide was responsible for the death of neurons, and so the neurons continued to die.

Patrik Brundin and Richard Wyse seem to suggest in this article:

http://www.sciencemagazinedigital.org/sciencemagazine/02_november_2018/MobilePagedReplica.action?pm=2&folio=521#pg25

that exenatide’s mechanism of action involves its suppression of microglial activation. So I wonder if the attacks of microglia on neurons tend not to control actual neuronal fatality, while the PARP-based mechanisms (described in that article as separate from the microglial ones) that are not affected by microglia / innate immunity are the determining factors so far as the actual deaths of neurons are concerned.

Some of the therapies my partner (who has PD) has been using are aimed at microglial activation; none of them are aimed directly at PARP. So if this shaky hypothesis of mine is correct, then that could be kind of bad news for us.

However, we are also using ubiquinol, which helps mitochondria to perform better, and thus might interfere somewhat with PARP-based neuronal death. And we are also using NAC, whose antioxidant capabilities might reduce the contribution that oxidative stress makes toward PARP overactivation.

So that very shaky hypothesis would seem to be somewhat consistent with the overall slow rate of progression that we have experienced. Maybe the missing ingredient for us to stop progression (as least in the substantia nigra area) would be a PARP inhibitor. Although that has problems of its own, including the possibility that it might cause cancer. But it might nonetheless be what we are lacking in our attempt to completely halt progression (even if it is not really what we *need*, given its potential toxicity).

LikeLike

Lou – I think you have previously acknowledged elsewhere that the positive slower rate of decline you are experiencing may just be your partner’s natural path – due to the form of PD or the underlying DNA or whatever he/she has. Just wanted to clarify that it may or may not be the supplements your partner takes, but it seems like they help

LikeLike

It’s true we can’t know from any one person’s experience whether a slower rate of decline is due to heredity, exercise, diet, supplements, or whatever. I have no reason to believe that my partner is, or is not, genetically better equipped to resist the ravages of the illness. But so far as I can determine through a crude comparison with other patients, as reported in the largest study of PD progression I’ve found, she’s doing better than more than 70 percent of patients at her number of years from diagnosis. I personally believe that the supplements she is taking are significantly responsible for that better than average progression.

LikeLike

In my comment above, I overlooked the fact that the last 12 weeks was a washout period during which no exenatide was administered. It appears, then, that exenatide had an initial, one-time, *improvement* in MDS-UPDRS, and was then able to *maintain* that improvement without further decline of the patient’s motor abilities, so long as the drug was being administered. During the washout period, however, the (erstwhile) exenatide group actually *gained* on the still-monotonically-increasing control group, closing the gap by a full point from week 48 until week 60.

That behavior seems more consistent with the exenatide rescuing some neurons that were in an intermediate stage of decline during the first 12-week interval, restoring the ability of these ailing neurons to produce dopamine, and from that point forward, preventing further deaths of the entire population of dopamine neurons, so long as the substance was being administered.

It’s a little concerning that there might have been some kind of rebound effect indicated by the faster progression measured once the drug had been discontinued. But one answer, I suppose, would be that patients can just keep taking it.

Now that I understand the study a little better, I can see why there would be some significant excitement regarding the repurposing of exenatide for the treatment of PD patients.

I do wonder whether there might be similar results would be recorded from a combination of non-patented substances such as ubiquinol, EGCg, baicalin and NAC. The combination of these substances will probably never receive the kinds of clinical testing that exenatide (with its multi-modal action combined in a single drug) has received in this study. So it may be that we’ll never know the answer to that question.

LikeLike

I’m wondering if that accelerated (i.e., faster than controls) increase in MDS-UPDRS during the final 12-week washout period could be read as a sign that progression was continuing and only symptoms were being suppressed. If the washout interval were to be extended, and it kept increasing faster than controls at that rate of one point per 12 weeks, it would catch up with the control group in another 36 weeks.

Of course, it is possible that *some* of the benefit was due to symptom suppression, and some was due to slower progression.

It would be interesting to see a follow-up after treatment was discontinued, to see if it the exenatide group ended up retaining some lasting benefit vs. the control group from its 48 weeks of active treatment, after that treatment was halted, just as happened in the two-year follow-up from the earlier, non-blinded, study.

LikeLike

HUGE thanks to you for this thorough summary, especially valuable for those of us who don’t have access to a Lancet subscription and so can’t read the original report in full without stumping up $32. Thanks too for all the references to earlier work.

Do you know of any longer-term trials that are already in (or soon to be in) progress? Given that the researchers involved have known for many months that the results were extremely promising, you might hope that there would be strong motivation to begin setting up further work without waiting for publication of this report. Seems to me there’s also a very strong case for these researchers to continue to follow up their trial cohort to see how things progress now that neither group is receiving Exenatide.

Thanks again and, as you say, it’s exciting news for the community.

Jonathan

LikeLike

Hi Jonathan,

Thanks for the comment.

I have to say that I found it unbelievable when this report was released that it was not OPEN ACCESS. I have tried to keep my thoughts on this quiet, but SERIOUSLY this is possibly one of the biggest publications in Parkinson’s disease research for decades, and the vast proportion of the affected community can’t access it?!?!? Could somebody please walk me through the logic of that decision. I’d better stop here before I go too far.

There is a clinical trial that is currently recruiting for another GLP-1 agonist called Liraglutide (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02953665), and there are plans underway for phase II/III studies from the current results (I believe there will be more on this announced soon).

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Looks like someone heard you, because it seems now to be freely available online:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5831666/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Simon,

Great review! I fully agree that it’s crazy that the actual report isn’t available for PWP for free given the importance of this research. I will be happy to email a copy to anyone with PD who contacts me.

I’m not as concerned as others about the relatively small difference, which was statistically significant, between the groups. Exenatide is believed to slow PD progression more so than reverse it. One year is not that much time in the normal progression of PD symptoms. I think the mild improvement in the test group compared to the mild deterioration in the placebo group is about all you could have hoped for over the course of one year. I also think that difference, along with the DatScan results, is “indicative” of the drug effect being neuroprotective rather than just symptomatic. I would imagine that the Phase 3 trial, which will happen sometime in the future, will be longer term. It will probably be in the range of three years, like the design of the current ongoing Isradipine. Unfortunately, that’s the time that is needed to see meaningful differences in progression compared to a placebo.

Best,

Gary

LikeLike

Sorry, but I left out the word “trial” after Isradipine in m y next to last sentence above.

LikeLike

Hi Simon,

In Athauda paper you posted on GLP there is assumption that Insulin resistance initiating PD. Two huge holes in that hypothesis:

1. In previous studies you pointed out that fat people less PD and thin or average build higher risk. Of course fat people are the people with insulin resistance. (fat people with insulin resistance much higher risk of AD)

2. More important:

Beta cells in pancreas (like melanocytes that give rise to melanoma) arise from Neural crest and have autonomic innervation. Therefore, insulin resistance in PD, the pancreas can be seen as just one more structure hit by prion like progression of a-syn.

LikeLike

I take another medicine, vitozia, fir my Type 2 diabetes. Will it have the sane effect on my Parkinsins than Exanatide?

LikeLike

This is one of the most encouraging and important Parkinson’s Disease related studies in decades yet four years have elapsed and PwP continue to deteriorate while we wait for a definitive determination of exenatide’s efficacy. Is anyone else frustrated?

LikeLike

Does anyone think it’s odd that there are about 5 years between the readout of the Phase 2 exenetide study in 2017 and the start of the Phase 3 Exenetide-PD3 study (started in 2022)? Why was that? Also, not sure why AstraZeneca is not executing the phase 3 study. If they thought it was a promising treatment for PD, they would as it would bring in sales for exenetide. As it is, this does not appear to be a label-enabling study (i.e, the drug would not get approval to be used in PD based on the UCL phase 3 study). Not sure why AZ is not doing more to get this on the label. Any insight on the delay between studies or AZ’s lack of interest?

LikeLike