|

Dopamine agonist treatments are associated with approximately 90% of hyper-sexuality and compulsive gambling cases that occur in people with Parkinson’s disease. This issue does not affect everyone being treated with this class of drugs, but it is a problem that keeps popping up, with extremely damaging consequences for the affected people who gamble away their life’s saving or ruin their marriages/family life. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is yet to issue proper warning for this well recognised side-effect of dopamine agonists, and yet last week they gave clearance for the clinical testing of a new implantable device that will offer continuous delivery of dopamine agonist medication. In today’s post, we will discuss what dopamine agonists are, the research regarding the impulsive behaviour associated with them, and why the healthcare regulators should acknowledge that there is a problem. |

Dopamine. Source: Wikimedia

Before we start talking about dopamine agonists, let’s start at the very beginning:

What is dopamine?

By the time a person is sitting in front of a neurologist and being told that they ‘have Parkinson’s disease’, they will have lost half the dopamine producing cells in an area of the brain called the midbrain.

Dopamine is a chemical is the brain that plays a role in many basic functions of the brain, such as motor co-ordination, reward, and memory. It works as a signalling molecule (or a neurotransmitter) – a way for brain cells to communicate with each other. Dopamine is released from brain cells that produce this chemical (not all brain cells do this), and it binds to target cells, initiating biological processes within those cells.

Dopamine being released by one cell and binding to receptors on another. Source: Truelibido

Dopamine binds to target cells via five different receptors – that is to say, dopamine is released from one cell and can bind to one of five different receptors on the target cell (depending on which receptor is present). The receptor is analogous to a lock and dopamine is the key. When dopamine binds to a particular receptor it will allow something to happen in that cell. And this is how information from a dopamine neuron is passed or transmitted on to another cell.

Dopamine acts like a key. Source: JourneywithParkinsons

The five different dopamine receptors can be grouped into two populations, based on the action initiated by the binding of dopamine. Dopamine receptors 1 and 5 are considered D1-like receptors, while Dopamine receptors 2,3 and 4 are considered D2-like receptors. Through these various receptors, dopamine is influential in many different activities of the brain, especially motor co-ordination.

It is reasonable to say that the bulk of the dopamine in the brain is involved with the regulation of movement.

How is dopamine involved with movement?

When you are planning to move your arm or leg, the process required for actually initiating that action begins in an area of the brain called the prefrontal cortex (it is the green area in the image below). The prefrontal cortex is where we do most of our actual ‘thinking’. It is the part of the brain that makes decisions with regards to many of our actions, particularly voluntary movement. It is involved in what we call ‘executive functions’ – pulling together all the available information from other parts of the brain, and deciding what to do and when to do it.

Areas of the cortex. Source: Rasmussenanders

Now, the prefrontal cortex might come up with an idea: ‘the left hand should start to play the piano’. The prefrontal cortex will communicate this idea with the premotor cortex (the orange area behind the prefrontal cortex in the image above) and together they will send a very excited signal down into the an area in the brain called the basal ganglia. In this scenario it might help to think of the cortex as hyperactive, completely out of control toddlers, and the basal ganglia as the no-nonsense parental figure. All of the toddlers are making demands/proposals and sending mixed messages, and it is for the inhibiting basal ganglia to gain control and decide which message is the best to send on to another important participant in the regulation of movement: the thalamus.

A brain scan illustrating the location of the thalamus in the human brain. Source: Wikipedia

The thalamus is a structure deep inside the brain that acts like the central control unit of the brain. Everything coming into the brain from the spinal cord, passes through the thalamus. And everything leaving the brain, passes through the thalamus. It is aware of most everything that is going on and it plays an important role in the regulation of movement. If the cortex is the toddler and the basal ganglia is the parent, then the thalamus is the ultimate policeman.

But where does dopamine come into the picture?

I’m getting to it.

In Parkinson’s disease, we often talk about the loss of the dopamine neurons in the midbrain as a cardinal feature of the disease. When people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, they have usually lost approximately 50-60% of the dopamine neurons in an area of the brain called the substantia nigra.

The dark pigmented dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source:Memorangapp

The midbrain is – as the label suggests – in the middle of the brain, just above the brainstem (see image below). The substantia nigra dopamine neurons reside there.

Location of the substantia nigra in the midbrain. Source: Memorylossonline

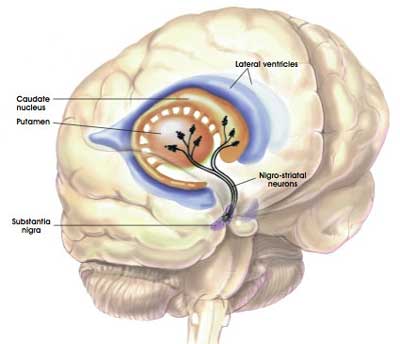

The dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra generate dopamine and release that chemical in different areas of the brain. The primary region of that release is the basal ganglia, particularly two areas of that structure called the putamen and the Caudate nucleus. The dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra have long projections (or axons) that extend a long way across the brain to the putamen and caudate nucleus, so that dopamine can be released there.

The projections of the substantia nigra dopamine neurons. Source: MyBrainNotes

In Parkinson’s disease, these ‘axon’ extensions that project to the putamen and caudate nucleus gradually disappear as the dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra are lost. When one looks at brain sections of the putamen after the axons have been labelled with a dark staining technique, this reduction in axons is very apparent over time, especially when compared to a healthy control brain.

The putamen in Parkinson’s disease (across time). Source: Brain

Under normal circumstances the dopamine neurons release dopamine in the basal ganglia which helps to calm down the excited signal coming from the cortex and also make the basal ganglia less inhibited. This acts as a kind of lubricant for movement.

With the loss of dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s disease, however, there is an increased amount of inhibitory activity in the basal ganglia. And as a result, the motor system is unable to work properly. And this is the reason why people with Parkinson’s disease have trouble initiating movement.

So that is why we treat people with Parkinson’s disease with dopamine-based treatments?

Exactly.

One of the primary treatments for Parkinson’s disease – Levodopa – is an ingredient in the production of dopamine.

How does Levodopa work?

When you take an Levodopa (or L-dopa) tablet, the pill will be broken down in your stomach and the Levodopa chemical will enter your blood through the intestinal wall. Via your bloodstream, it arrives in the brain where it will be absorbed by cells. Inside the cells, another chemical (called DOPA decarboxylase) then changes it into dopamine. And that dopamine is released, and that helps to alleviate the motor features of Parkinson’s disease.

The production of dopamine, using L-dopa. Source: Watcut

Outside the brain, there is a lot of DOPA decarboxylase in other organs of the body, and if this is not blocked then the effect of Levodopa is reduced in the brain, as less Levodopa actually reaches the brain. To this end, people with Parkinson’s disease are also given Carbidopa which inhibits DOPA decarboxylase outside of the brain (Carbidopa does not cross the blood-brain-barrier, or the BBB in the image above which is a protective film covering the entire brain).

Why don’t we just use dopamine?

We can not use dopamine directly because:

- It can not cross the blood brain barrier, and

- It is broken down very quickly in the body. There are lots of enzymes floating around that can break dopamine down so that it doesn’t do anything it’s not supposed to.

Couldn’t we just design drugs that act like dopamine, but don’t have these problems?

We can, and we have.

They are called dopamine agonists.

What is an agonist?

On the surface of a cell, there are receptors which act as switches for certain biological processes to be initiated. Receptors will wait for a protein to come along and activate them or alternatively block them. The activators are called agonists, while the blockers are antagonists.

Agonist vs antagonist. Source: Psychonautwiki

Dopamine agonists are drugs that activate one or more of the five dopamine receptors. In effect, this class of drugs acts just like dopamine.

So why don’t we just use them instead of Levodopa?

You would think that is it just that simple: Dopamine agonist are drugs that act like dopamine, so let’s just use them.

And dopamine agonists have offer some major benefits over other Parkinson’s disease associated medications (especially Levodopa) in that they:

- Stimulate dopamine receptors directly rather than require further processing inside the brain, which uses up essential dietary molecules.

Source: Wearingoff

- Have a longer half life (meaning that they last longer in you body) than Levodopa and some of the other treatments

- Have a reduced risk of dyskinesias

These are all good reasons for shifting everyone to dopamine agonists right?

But the thing is: dopamine agonists have a dark side.

How bad is their dark side?

In 2003, this research report was published:

Title: Pathological gambling associated with dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Driver-Dunckley E, Samanta J, Stacy M.

Journal: Neurology. 2003 Aug 12;61(3):422-3.

PMID: 12913220

In this study, researchers from the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Research Center (Phoenix, Arizona) collected data relating to all of the people with Parkinson’s disease that had attended their clinic between May 1st, 1999, to April 30th, 2000. A total of 1,884 people with Parkinson’s were seen during that 12-month period. 1,281 of these individuals were being treated with dopamine agonists. Nine of these people (7 men and 2 women) were found to have developed gambling behaviour severe enough to cause financial hardship (two reported losses greater than $60,000). None of the subjects on levodopa therapy alone or on any other DA-based treatment were found to have symptoms of obsessive or excessive gambling.

This report was quickly followed by more, including this one:

Title: Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease.

Authors: Dodd ML, Klos KJ, Bower JH, Geda YE, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE.

Journal: Arch Neurol. 2005 Sep;62(9):1377-81. Epub 2005 Jul 11.

PMID: 16009751 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, researchers from the Mayo Clinic (Minnesota, USA) describe 11 cases of people with idiopathic PD who had recently developed pathological gambling (between 2002 and 2004). And some of these cases were extreme: Case #6 begun to gamble “uncontrollably” and lost more than $100 000. In addition, he began compulsive eating (gaining significant weight) and developed an obsession with sex (engaging in extramarital affairs) and pornography.

All 11 cases were taking therapeutic doses of a dopamine agonist. For 7 of the cases, pathological gambling developed within 3 months of starting the agonist. The gambling problem was resolved after the agonist treatment was discontinued. The investigators noted that disproportionate stimulation of dopamine receptor 3 by the agonists may be underlying the problems.

Subsequent literature suggests that compulsive behaviours affect between 6 -23% of people taking dopamine agonists (Click here and here to read more about this). One report proposes that impulse control problems may be unrecognised in more than 50% of cases (Click here for more on this).

And if you think that this problem is only an issue for the Parkinson’s disease community, you would be wrong. There are also numerous reports of people developing pathological gambling problems while taking dopamine agonists for other conditions, such as this report dealing with restless legs syndrome:

Title: Pathologic gambling in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopaminergic agonists.

Authors: Tippmann-Peikert M, Park JG, Boeve BF, Shepard JW, Silber MH.

Journal: Neurology. 2007 Jan 23;68(4):301-3.

PMID: 17242339

In this study, the investigators report on three patients who were being treated at their clinic. All three developed pathologic gambling behaviour while receiving dopamine agonists treatment for restless legs syndrome.

How is the problem developing? What causes it?

We don’t really know. Over stimulation of dopamine receptor 3 by the agonists does appear to be an issue and this may relate to the location of dopamine receptor 3 within the brain. They are particularly abundant in an area called the limbic system which is involved with our sense of emotion and motivation. Over stimulation of this region could explain the increase in impulsive behaviour.

And it is important to realise that this impulsive behaviour generally disappears as soon as the dopamine agonist treatment is reduced or halted.

But back to our story:

More and more report were published until eventually, this report was appeared:

Title: Reports of pathological gambling, hypersexuality, and compulsive shopping associated withdopamine receptor agonist drugs.

Authors: Moore TJ, Glenmullen J, Mattison DR.

Journal: JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec;174(12):1930-3.

PMID: 25329919 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators analysed 10 years’ worth of public submissions to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. The researchers were specifically looking for reports of impulse control disorders, and they then looked at which prescription medications were associated with them.

The FDA data identifies 1,580 cases of “behaviors associated with impulse control disorders”. When they analysed their results, guess what they found?

Taking into account all of the drugs currently available on the market, it is rather disturbing that just under half (or 710 of the 1580) of the reported cases were associated with dopamine receptor agonists. So of all the thousands of different types of drugs available, just one class is responsible for almost 50% of the “behaviors associated with impulse control disorders”.

The researchers concluded their study by writing: “At present, none of the dopamine receptor agonist drugs approved by the FDA have boxed warnings as part of their prescribing information. Our data, and data from prior studies, show the need for more prominent warnings“.

At this point even the Michael J Fox foundation were suggesting that a ‘Black box’ warning label on this class of medication was needed (Click here to read their thoughts on the matter – dated October 24th, 2014)

So what has the FDA done about this?

That’s a really interesting question (and this is where we come to the heart of the matter).

The FDA. Source: Vaporb2b

In 2012, the FDA published a comment about dopamine agonists and the risk of heart problems (Click here to read that comment). According to their clinical study data, 12 out of 4157 individuals taking a particular dopamine agonist suffered an incidence of newly diagnosed heart failure (compared 4 out of 2820 control subjects – that is 8 in 4000 if made comparable to the treatment group).

The FDA decided that that problem warranted a comment, which is “in keeping with FDA’s commitment to inform the public about its ongoing safety review of drugs” (Source).

There has never been an FDA statement/comment (that I am aware of – happy to be proven wrong!) regarding compulsive behaviour though.

Que? Has no one done anything about this???

In June of 2016, an advocacy group – Public Citizen’s Health Research Group – submitted a petition (Click here to read that petition) to the FDA demanding that place ‘Black Box’ warnings be manditory for “for all dopamine agonist drugs currently approved in the U.S. (apomorphine, bromocriptine, cabergoline, pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine)”

The FDA politely responded to the petition on the 20th December 2016.

Their letter in full reads:

Dear Petitioners,

I am writing to inform you that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet resolved the issues raised in your citizen petition received on June 29, 2016. Your petition requests that the Agency immediately require a boxed warning and risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for dopamine agonist drug products due to an alleged risk of developing certain impulse-control problems and compulsive behaviors.

FDA has been unable to reach a decision on your petition because it raises complex issues requiring extensive review and analysis by Agency officials. This interim response is provided in accordance with FDA regulations on citizen petitions (21 CFR 10.30(e)(2)). We will respond to your petition as soon as we have reached a decision on your request.

Carol J Bennett

Deputy Director Office of Regulatory Policy

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

That was December of last year, and the FDA is yet to reach a decision on the petition (for an excellent STATnews article on the saga surrounding this petition – Click here).

So what happened last week?

The FDA gave clearance for the clinical testing of a new implantable device that will offer continuous delivery of dopamine agonist medication. The application for testing this new implantable device was submitted in December 2015, and it was given the green light last week.

Now, call me cynical, but that’s a rather quick turn around when you consider that 14 years after the first reports of issues with this class of drug (and countless reports since then), and the FDA suggests that they still need more time to think about whether a black box warning label is required on the pill version.

While I appreciate that they have a very difficult task and limited resources, I still struggle to understand their logic here.

And the FDA is not alone here.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe has recommended having warning labels on dopamine agonists, but this is in relation to the risk of fibrosis (the formation of fibrous tissue in some body structures, particularly the heart – Click here to read more about this). They have made no mention of the possibility of impulse control issues developing with inappropriate use of dopamine agonists.

So what does it all mean?

You do not need to hang around a Parkinson’s disease clinic before you start to hear stories of people gambling all of their life savings away after being put on dopamine agonists.

As I said above, this problem does not affect everyone on this class of drugs. But the very least we could do is put big warning labels on the medication to make people aware and attentive to the signs of problematic behaviour. This is the job of the health regulators, and given that this issue has been discussed for 14 years now and peoples lives have been irreparably damaged during that time, it is safe to say that the regulators have taken too long to address this matter.

I do not think that this case of drug should be removed from the clinic; It would be wrong to throw the baby out with the bath water. But I do wonder whether it would be more prudent to better understand why the impulsive behaviour problems exist before developing further products around them.

The banner for todays’s post was sourced from Youtube

Government….At least we have good posts like this to educate us :). For me at least, the community quickly informed me of the risks associated with these. And it seems like most docs I’ve talked to are savvy.

Also inersting how doctors will knowingly prescribe a dopamine agonist despite the risks(label or not), but prescribing isradipine, for example, in the hopes of disease modification is taboo even with the decades of safety data.

LikeLike

Hi Double,

I suspect physicians approach the problem like a numbers game: if 1 in every 10 people have issues with these drugs let’s give everyone the drug and when something goes wrong we can simply take that particular person off the drug or simply lower the dose. Problem solved, right? The issue with this approach, however, is the damage done while waiting for acknowledgement that something has gone wrong.

It is good that the community is aware and cautioning fellow sufferers about the dangers. Shame the regulators aren’t following the example.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Excellent article Simon! I have long been alarmed at newly dx PD being put on agonists first for as long as possible. As you know, this is to extend the time before L-Dopa is introduced because of its relatively short life before the backlash of dyskinesias.

Certainly in YOPD, agonists seem to have other knock-on effects that are not seen in elder-onset that are worrying. Ultimately, if one is dx with Pd aged [say] 24 and are on agonists, the outcome seems to be more fierce in damaging side effects; I hear of mood swings, parasomnias starting too early (although agonists are helpful for RLS), allergies. Love to know how and why agonists behave differently in YOPD?

Ultimately, is the choice of agonist v levodopa the lesser of two evils?

Many thanks!

LikeLike

Amen sister

LikeLike

Ditto Maulebach!

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

Thanks for the comment – glad you liked the post.

A lot more research is needed on this issue before we will be able to answer some of your questions. The thing about dopamine agonists is that they work really well for a lot of people, and my biggest worry is that by not acting and providing better guidance the health regulators are going to let this class of useful drugs become completely stigmatised to the point that no one wants to use them. The prudent thing to do is warn newly diagnosed people to keep an eye out for anything that looks like impulsive behaviour, at which point dose could be lowered (halting can result in withdrawal-like symptoms) or other medication could be considered. The regulators need to act before we reach that point… if we are not there already.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I have heard from one person who lost everything…except her marriage (and that was in jeopardy) because of this. Many others have posted about the problem. Why wouldn’t that warning be the FIRST thing listed as side effects? If educated about it, PwP and the care partners would be able to watch for signals of issues in order to avoid disastrous activity!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sherry,

You make a good point – especially as PwPS can often control any uncommon compulsiveness if they’re aware it could happen. Me & hubby are lucky: I watch for odd behavior & bring it to him. He ruminates and adjusts. But too many are living this unaware or worse, solo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sherryl,

Matt Eagles shares a very personal experience with dopamine agonists on the Parkinson’s Life website:

http://parkinsonslife.eu/matt-eagles-parkinsons-impulse-control-disorders/

It is ridiculous though that reading these sorts of articles is how many newly diagnosed individuals find out about these sorts of issues. A warning label would surely help.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

My experience has been that in the UK I have been warned repeatedly about the possibility of compulsive behaviour and the PIL covers these dangers. Keith W.

LikeLike

Hi Keith,

Thanks for your comment. It seems that everyone’s experience with this class of drugs is different (both the effect and the advice provided). The community is certainly becoming more aware of the potential dangers.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike