|

In this post, I will address a question that I get asked a lot: What would you do if you were diagnosed with Parkinson’s today? Before we start, please understand that there is no secret magical silver bullet to be discussed in the following text. Such a thing does not exist, and anyone offering such should be treated with caution. Rather, in this post I will spell out some ideas (or a plan of attack) of what I would consider doing if I was confronted with a diagnosis today and how I would approach the situation.

|

Source: Fifteendesign

Source: Fifteendesign

An email I received this week:

Hi Simon,

Love the website. I think you are amazing and I love your dreamy eyes and perfect hair.

[ok, I may be exaggerating just a little bit here]

Given everything that you have read about Parkinson’s, what would you do if you were diagnosed with Parkinson’s today?

Kind regards,

John/Jane Doe

I get this kind of correspondence a lot, and you will hopefully understand that I am very reluctant to give advice on this matter, primarily for two important reasons:

- I am not a clinician. I am a former research scientist who worked on Parkinson’s for 15 years (and now help co-ordinate the research at the Cure Parkinson’s Trust). But I am not in a position to be giving medical/life advice.

- Even if I was a clinician, it would be rather unethical for me to offer any advice over the internet, not being unaware of the personal medical history/circumstances in each case.

While I understand that the question being asked in the email is a very human question to ask – particularly when one is initially faced with the daunting diagnosis of a condition like Parkinson’s – this is not an email that I like to receive.

I am by nature a person who is keen to help others, but in this particular situation I simply can’t.

Why not?

I am very much in the “Parkinson’s is a syndrome” camp, which makes any kind of blanket advice rather redundant.

What do you mean by the statement “Parkinson’s is a syndrome”?

You will often hear the phrase: “If you meet one person with Parkinson’s, you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s“.

The statement is correct as it captures the wide variety of symptoms and clinical features that members of the Parkinson’s community share. Some folks are tremor dominant, while others suffer rigidity. Some have very rapid progression, while others have the condition for decades. Some have genetic risk factors that make them more vulnerable to developing Parkinson’s, while others have never been sick a day in their lives until suddenly the neurologist says “I think you have…”

Source: Assessment

Source: Assessment

But what do you mean by “Parkinson’s is a syndrome”?

Some medical definitions for you:

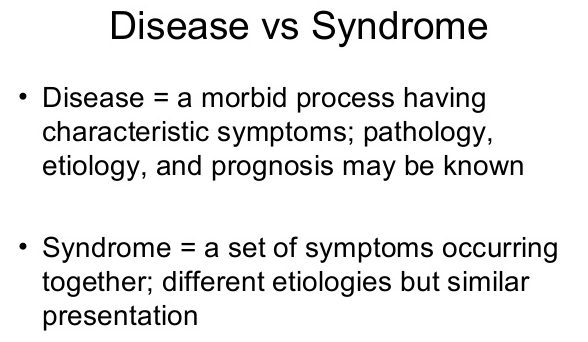

A disease is a definitive pathophysiological response in the body due to specific internal or external factors, which has a set characteristic of signs and symptoms. Key to the label of ‘disease’ is the definitive influencing factor (e.g., virus, bacteria). For example, Poliomyelitis (or simply ‘polio’) is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus.

A disorder is a disruption of regular bodily function or structure. Disorders are generally due to an internal/intrinsic abnormality (for example, a birth defect or a genetic malfunction).

A syndrome is a collection of conditions that share similar features and symptoms, but without an identifiable cause.

Source: Slideshare

Source: Slideshare

There is a lot of overlaps between these definitions, and the situation is not helped by the labelling of some conditions which have very specific causes as ‘syndromes’ (Down syndrome, for example, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21).

But you hopefully get the idea – we do not know what causes ‘Parkinson’s disease’, but my personal opionion is that we are dealing with a combination of conditions that share similar features. And thus, when someone writes to me and says that they have Parkinson’s, I am always left wondering ‘what type of Parkinson’s?’. Do they have young onset Parkinson’s? A particular genetic risk factor? Are they tremor dominant? Etc.

So you can’t give advice because you are not a clinician and you don’t know what type of Parkinson’s each person has?

Exactly.

In addition, there is something extremely obscene about writing this kind of a post. While I am fascinated by the research/science of Parkinson’s, I certainly do not feel I am in any kind of position to be dishing out advice.

So you are not going to offer any advice?

I do not like to leave people with no information.

And as I was proof reading the recent ‘Outlook for Parkinson’s in 2019‘ post (Click here to read that post), I was really struck by how bewildering it would be to be a butcher/baker/candlestick maker, suddenly diagnosed with Parkinson’s and faced with the decision of which clinical trial to apply for.

Even with a background in science, it would be very difficult to judge which path to take.

Source: Englishlessons-houston

Source: Englishlessons-houston

So I thought I would write this post, not so much as advice or a set of instructions, but rather as a brain storming of ideas that readers could explore further. And then ideally, perhaps readers could also share their own thoughts/advice on what they have tried/experienced. And maybe something useful could grow from there.

Thus, all of that said, if I was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s today (I am under 50 years of age, but much of what follows is applicable to older onset as well), I would do several things as part of dealing with the situation:

1. Know thyself

By this I mean, I would try to learn as much as I can about myself from the standpoint of Parkinson’s. And on the individual level, if Parkinson’s is a syndrome knowing thyself is more important than actually knowing thy enemy.

Socrates taught that: The unexamined life is not worth living. Perhaps he was right, but for me an exploration of life after a diagnosis of Parkinson’s would start with having my DNA sequenced.

Source: Futurism

Having one’s DNA analysed is a very personal choice, and no one should feel that they are being forced into doing it. But if I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s today, one of the first things I would personally want to know is whether there are any genetic risk factors present in my DNA.

There are many small regions of DNA that are called genes. Genes are sections of DNA that provide the instructions for making particular proteins. Small variations or errors exist in some of our genes, and some of those variations can make us vulnerable to developing particular conditions. These variations are referred to as genetic risk factors, and there are genetic risk factors associated with increased risk of developing Parkinson’s (Click here and here to read more about the genetics of Parkinson’s).

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

And having one’s DNA sequenced is not a decision I would take lightly. I would do it knowing full well that there is the potential for me to discover other nasty things about my genetic make up that I may not want to know (Click here for some things to consider before getting your DNA sequenced).

I would do this using both my doctor and a genetic counsellor (who could better help me with understanding what the gained information could mean).

It is important to understand that carrying a particular Parkinson’s genetic risk factor does not necessarily mean that you are going to develop Parkinson’s. Nor does it mean that one’s Parkinson’s can necessarily be attributed to carrying a particular Parkinson’s genetic risk factor.

But this would be my starting point.

Why?

Because this is where the resesarch behind many of the clinical trials is focused, and if I have a particular genetic risk factor, I would be focusing on the clinical trials that relate to that genetic variation.

And where would you get your DNA sequenced?

I would seek a full DNA sequence – most of the current direct-to-consumer DNA sequencing companies only sequence small fractions of your DNA. But there are some companies now offering much deeper sequencing (Click here to read a recent SoPD post on one such company). And would I do this knowing that most of the information that I will receive back will be useless, but rather than simply learning genetic status regarding the common risk factors (such as GBA or LRRK2), I would be able to have a look at a wider variety of the possible genetic variants.

And if I was a carrier of a more common genetic variant (such as GBA or LRRK2), I would then get my DNA sequenced at several of the direct-to-consumer DNA sequencing companies.

Why?

It would be an expensive process, but given that the world appears to being divided up genetically, it would seem sensible to have knowledge of my status in several places.

What do you mean?

Recently the Pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and the direct-to-consumer DNA sequencing company, 23andMe signed a $300M equity investment and a four-year research collaboration (Click here to read the press release from GSK).

Source: Medium

Source: Medium

GSK views this deal as a means of speeding up their clinical trial programme for the development of LRRK2 inhibitors for Parkinson’s – they say as much in some of their recent presentations (Click here to read more about this). And because some of these genetic variants are extremely rare – even within the Parkinson’s community – they need all the help they can get for recruiting people to take part in their clinical trial. A clinical study of people with LRRK2-G2019S associated Parkinson’s will need to genotype (or DNA sequence) approximately 100 people with Parkinson’s to identify just one individual with a LRRK2-G2019S genetic mutation – that is how rare some of these genetic variants are.

23andMe, however, has more than 10,000 ‘re-contactable’ individuals with Parkinson’s in their database, approximately 3,000 of those ‘re-contactable’ individuals have LRRK2 G2019S carriers. By paying 23andMe for access, GSK can skip a a lengthy recruitment process. Thus, speeding up the clinical trial process.

And GSK/23andMe are not the only companies taking part in such deals. Denali Therapeutics and Centogene recently signed a similar sort of deal (Click here to read the press release).

Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

If I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s I would probably seek to take part in a clinical trial, and knowledge of my genetic status would heavily influence which kinds of clinical trials I would be focusing on. For example, if I carried a LRRK2 variant, I would actively seek out LRRK2-based trials, and if I have an alpha synuclein variant I would look towards the alpha synuclein targetting immunotherapy tirals. By having my DNA status on multiple databases, I would increase my chances of being contacted by the companies running the trials.

You would take part in a clinical trial?

My current thinking is ‘Yes I would’. But that would be my personal choice.

And please understand, that this is all hypothetical. Taking part in a clinical trial is a very personal decision, and it is one that should not be taken lightly. These experimental approaches that are being tested in the clinic could make things better, or make things worse. One should not leap in without weighing all of the options/possible outcomes.

I see. What else can I do with my genetic data?

Research.

Even if I chose not to take part in a clinical trial, once I knew my genetic status, I would approach several research lab working on any particular genetic variants that I might have and ask how I could possibly help their efforts.

And I would make sure that biological samples of myself are made available in biorepository resources, such as the BioFIND study:

Launched in 2012, by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and NINDS, this study collected both clinical data and biological samples (DNA, etc) from 119 people with Parkinson’s and 96 healthy control subjects. Recruitment began in 2012 and closed in March 2015 (for more information, you can click here). The idea of this study was to “produce the most comprehensive and long-ranging dataset available for biomarker discovery work throughout the PD community”

Launched in 2012, by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and NINDS, this study collected both clinical data and biological samples (DNA, etc) from 119 people with Parkinson’s and 96 healthy control subjects. Recruitment began in 2012 and closed in March 2015 (for more information, you can click here). The idea of this study was to “produce the most comprehensive and long-ranging dataset available for biomarker discovery work throughout the PD community”

Another example is the The Oxford Parkinson’s Disease Centre here in the UK:

This is a large longitudinal study, involving more than 1000 people with Parkinson’s who have had DNA and various bodily fluids collected (this project is supported by Parkinson’s UK). Here is a video of Prof Michelle Hu discussing the study in 2015:

This is a large longitudinal study, involving more than 1000 people with Parkinson’s who have had DNA and various bodily fluids collected (this project is supported by Parkinson’s UK). Here is a video of Prof Michelle Hu discussing the study in 2015:

I would make sure that various pieces of me are available to help the overall process of the research focused on Parkinson’s.

What if I don’t want to do the genetic test or give myself to research?

Perfectly understandable.

Whether I got a genetic test conducted or not, the next step in ‘knowing thyself’ process for me would be a full body check up.

A full body what?

We live in amazing times – Human Longevity Inc. offers a daylong series of scans, tests, and genomic analysis called Health Nucleus. It is a full body check up.

This company foundered by genetics pioneer Dr Craig Venter offers individuals a combination of whole genome sequencing, a full-body MRI, metabolic and microbiome analysis, as well as cognitive testing.

(This is not an advertisement or endorsement of the product, I am simply mentioning it here as part of this exercise)

The problem is: it is rather expensive (US$25,000 at the time of writing) so I would probably not take this particular route.

But I would ask my doctor to do a lot of tests (bloods, cholesterol, urate, etc) and I would do this on a regular basis (every 3-6 months or so).

These tests would include:

- Complete blood and urine analysis

- Cardiac assessment (eg. resting electrocardiogram, etc)

- Cholesterol (for example, total cholesterol; HDL cholesterol; LDL cholesterol; triglycerides)

- BMI (Body mass index)

- Diabetes test

- Electrolytes (these are minerals found in the body, such as sodium, potassium and chloride)

- C-reactive protein (CRP) test (a test of inflammation in the body)

Basically anything that could be measured and potentially relevant to Parkinson’s.

But why??? What would be the point of doing this AFTER a diagnosis of Parkinson’s?

It’s all part of ‘knowing thyself’.

Many folks (including clinicians and researchers) will scoff at this perhaps and suggest that it is ‘over kill’, pointless tests; collecting data simply for the sake of collecting data.

But I would be seeking a ‘baseline’ measure on all of the tests that could be monitored over time – hence the regular testing. By collecting as much information about myself, we (my doctor and I) would be in a better position to decide what to do next. And these baseline measures would inlcude some basic measures of Parkinson’s – crude and imperfect as they may seem – such as sleep monitoring using a Fitbit like device (I currently use a Huawei Band 2 Pro, and I have found that I have poor deep sleep continuity and not enough sleep – I doubt the accuracy of the former and am focusing on improving the latter, but failing miserably).

Source: Huawei

Source: Huawei

On the SoPD website, we like to regularly discuss new technology that could improve the way monitoring Parkinson’s could be done (Click here, here, here, here and here to read examples of this).

Sounds like a lot of work. Is it?

Ideally it shouldn’t be.

Here at the SoPD, we are not fans of any tech that requires effort from the individual being monitored (such as smart phone apps or diaries) or that is too intrusive (eg. multiple sensors all over the body). In a perfect world, the systems of measurement would be continuous, quantitative and I would be able to go about my day completely unaware of them. We will be exploring this theme further in future posts.

It is important to appreciate the psychology of monitoring oneself.

As we all age, we will see ourselves slowly fall from grace, and with a progressive condition like Parkinson’s this situation could be amplified in some of the data collected. I would almost be inclined to be monitored blindly (that is, my doctor would be aware of the results but I would be blind). This is partly based on my own experience of monitoring my sleep – I have found that self monitoring of steps and sleep can be stressful (I need to go sleep, but I can’t because I am aware that I am being monitored! The clock ticks on and I get more anxious that I won’t get my hours of sleep) which affects results.

Need to sleep. Source: Trainright

Need to sleep. Source: Trainright

Moving on.

All of this information being collected would influence how I would seek to try and treat the condition. For example, if the full body tests highlighted inflammatory markers in the blood over time, I would seek out clinical trials targetting neuroinflammation (Click here to read a SoPD post about this).

2. Diet and exercise

I would definitely change my diet and exercise regime.

That is not to say that my diet is terrible at the moment, but I would remove some of the foods that have been associated with faster rates of disease progression, such as:

- Canned fruit

- Diet soda (carbonated drinks)

- Canned vegetables

- Fried food

- Beef

- Soda (carbonated drinks)

And I would increase levels of foods that are associated with a slower rate of Parkinson’s progression, such as:

- fresh vegetables

- fresh fruit

- nuts and seeds

- fish

- olive oil

- wine

- coconut oil

- fresh herbs

- the use of spices

We have previously discussed food and Parkinson’s – click here to read that post or watch this video of Dr Laurie Mischley – a guru when it comes to nutrition and Parkinson’s:

Would you try any supplements?

Whether I were to add any supplements to my diet would rely largely on what I discover about myself from the whole ‘Know thyself’ process. If I discovered that I have an alpha synuclein variant in my DNA, perhaps I would increase my intake of Epigallocatechin Gallate (or EGCG – click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic). If I lost my sense of smell, perhaps I would try Mannitol (Click here to read more about this).

As I have suggested, the answer to this question would depend entirely on what kind of Parkinson’s I would have, and what I would learn from the ‘know thyself’ process.

And what about exercise?

I would definitely change my exercise regime.

This change would basically involve shifting my exercise regime from its current status (nothing) to something more dynamic (regular gym/pool sessions).

And while I appreciate that the high impact exercise regime may be suggested to be beneficial for some individuals with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this), I would focus initially on low/mild cardio (cycling 3 – 4 times per week for 30 minutes) and lots of stretching (20-30 minutes each session). And again, this programme would be influenced by my observations I make while monitoring myself. Over time, if I see no change in levels of inflammation, I might increase activity to a more high impact exercise regime.

Regardless, any kind of exercise would be an improvement on my current situaiton (#noexcuses).

3. Focus

The third and final part of what I would do involves where I would focus.

I would focus my attention solely on what I can do, rather than what I can’t. This is borrowed from the mantra of Mike Lloyd.

Mike is one of my heroes. He just finished his 10th New York marathon!

Mike is one of my heroes. He just finished his 10th New York marathon!

Diagnosed with Parkinson’s 6 years ago AND being blind has not stopped him from doing what he feels he can do (http://www.theblindsportpodcast.com/). He does not waste time worrying about the things he has no control over. And he claims that he will keep doing the marathon gig, until he can’t and then he will simply focus his attention on something else. A powerful message – not just for people affected by a progressive condition. And he’s a kiwi – which helps!

I would focus on meditation/relaxation – something I don’t do enough of at the moment.

I would focus more on my family and friends – something I don’t do enough of at the moment.

I would focus on advocating for Parkinson’s – I would try to follow in the footsteps of the Tom Isaacs, Emma Lawtons, Sara Riggares, David Sangsters and Soania Mathurs of this world:

And a major part of any advocacy effort I would undertake would involve getting orphan disease status for some of the rarer forms of Parkinson’s.

Orphan disease status has many benefits, from tax advantages for biotech firms to short/smaller clinical trial programmes (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this). And getting orphan disease status designations for some of the rarer forms of Parkinson’s may have benefits for the wider Parkinson’s community as some of the therapies developed for one form of Parkinson’s, may also work for others. For those interested, Spotlight YOPD is active in this area of trying to have different forms of Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease (YOPD) designated as rare diseases.

And that is about it with regards to the whole “What would you do?” question.

And that is about it with regards to the whole “What would you do?” question.

Perhaps in the future I’ll come back and edit this post, adding in new things. But this is how I would currently deal with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s if I was confronted with such a situation.

Any thoughts on this post would be greatly appreciated. Back to the normal research format in the next post.

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR:

One of the books I gift the most is “How we die” by Dr Sherwin Nuland.

And as I say to the receiver of the gift: “You should never judge a book by its cover” (As a rule, I am selective as to who I gift this to; and never for Christmas or birthdays).

And as I say to the receiver of the gift: “You should never judge a book by its cover” (As a rule, I am selective as to who I gift this to; and never for Christmas or birthdays).

This book is a poetic set of reflections from a medical doctor who has sent his entire career watching ‘life’s final chapter’. There is science, wisdom and beauty on every single page. Nuland has a wonderful way with words, and I find myself constantly going back to this book.

Sherwin Nuland (1930 – 2014). Source: Theparisreview

Sherwin Nuland (1930 – 2014). Source: Theparisreview

My favourite part of the entire book is chapter 11.

Throughout the book, Nuland pushes the argument for returning some dignity to our last days of life. Rather than prolonging suffering in a futile effort to extend life a few short months, he implores the reader to let nature simply take its course.

But all of this changes in chapter 11, where he describes the moment he found out that his brother Harvey had cancer.

In an instant everything changed, and instead of “let nature simply take its course”, Nuland recalls how his thinking immediately became “we have to do whatever it takes to keep my brother alive” (And I’m not ruining the book by sharing this spoiler – there is so much more in this book. It should be required reading for first year medical students).

And this ‘situation-changing-the-thinking’ situation is an important part of this entire discussion. Context changes everything. Until you have faced down the beast, you really can’t be sure how you will react.

I can sit here writing about how I would be proactive and what I would do if faced with a diagnosis, but we both know that it all means zip until push comes to shove. No one can really be sure how they would react and what they would do until they are actually faced with the situation.

Thus, I fully appreciate the hypocrisy of writing this post and if I have offended/upset anyone by making it, I wholehearted apologise. I am sharing this post (after long consideration) in an attempt to stimulate discussion and share idea about what one could possibly consider when faced with a diagnosis (my personal approach you may note has all the hallmarks of a researcher). It will also serve as a place to send folks who contact me and ask the question “What would you do?“.

If you have any thoughts/criticisms/ideas on any aspect of this post (ideally based on personal experience), please feel free to share them in the comments section below or by contacting me directly.

I would really like to hear people’s thoughts on this.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from steemit

Thank you,Simon, for another thoughtful and inspiring post. I AM facing PD, and happily almost everything you mentioned is something I have personally incorporated. I am grateful for the things that I can do, and don’t waist much time or thought on what I can’t. I’m proactive in learning about PD, and participating in a clinical trial. I have strong, supportive relationships, and projects that keep me busy. I’m proactive in getting involved in PD advocacy. Finally, as I’ve already mentioned, I’m optimistic that improvements are near, and strengthened and grateful for all the research and efforts being expended toward such, as well as the efforts of people (especially you) who help me to understand the disease and the science. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

Thanks for your inspiring comment – that is a proactive attitude which I have a lot of respect for.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I’m guessing that you’ve already asked yourself the following question. Interested in your answer…

If you would take the above actions, and make those changes to diet, exercise, etc, upon a diagnosis of Parkinson’s, and if you currently have a non-zero chance of someday developing Parkinson’s, then why wait?

LikeLike

Hi David,

It is an interesting question. The sensible answer is: I really should make some of those changes myself. My honest answer however is: I currently live with the attitude that I am not going to live forever, so I will do as much as I can with what I have of today. This silly attitude results in me spending less time sleeping and exercising, and it will probably change immediately if something goes wrong health-wise. That said, I have in the last year become more mindful (which is rather popular I know, but appreciation and gratitude for what one has is important). And I do eat fairly healthy (largely thanks to my wife).

On the PD advocacy side of things, I have been to meetings with Spotlight YOPD, trying to get orphan status for different types of early Parkinsonisms, and I am keen to see that progress. That really needs the community to jump on the band wagon though and make some noise I suspect.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Thanks, Simon.

LikeLike

I would take a very long at exactly what Parkinson’s is I would keep my research contained to reliable resources like the MJF Foundation or research done in some of the larger Universities. There is a lot of information on the web that is not worth reading. Best I would change my diet to ensure that I only eat what is best for my body so would be ready for the long fight ahead. Lastly, I would join a good gym hire a trainer and get in the best shape in my life.

Sorry, I already have Parkinson’s going on 15 years now and that is what I would do. The better your health going in the longer it will remain so.

LikeLike

Hi Dale,

Thanks for your thoughtful comment – very much appreciated. I fully agree with the ‘better your health is’/’best shape in my life’ sentiment. That does seem like the best place to start the process.

A number of readers have asked about the idea of ‘knowing thy enemy’ and asking for advice as to which research/data to trust. This is going to have to be a separate post all together as it is a perennial problem for researchers in the field. I will try and have a crack at outlining something on this in a later post.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Hi Simon,

Thank you for the thought provoking post. I’m learning just how complex a phenomenon Parkinson’s is, and I think you’ve outlined the beginnings of a patient centred ‘contingency model’ here (with yourself as a hypothetical example). I understand, as you’ve noted, that different people have different values, capabilities and attitudes to risk – to me, these seem like more situational factors that can be taken into account, in deciding which approaches to use.

One of the ironies with Parkinson’s is that it saps one’s motivation and decision making capability – the very things that are most needed when navigating a complex situation. Anything that helps in this area is a scaffold that those with Parkinson’s can stand on.

Regards,

Paula

LikeLike

Hi Paula,

Thanks for your interesting comment. I actually suspect you may be on to something with the decision making/apathy aspect of Parkinson’s. I will look into this – it is a component of the process that I had not considered. Much appreciated insight.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I left a comment here yesterday, but it never appeared, perhaps because I apparently had a PD-related double keystrike typo in email address! It was a fabulous email, beautifully expressed, destined to change PD communication as we know it, but it’s gone now! Anyway, What would I do? Same stuff I did when DX age 61 back in 2007: try my best to figure out what I can do to understand my own form of PD & to improve my chances. I’ve done many of the things you mention. As a former technical librarian, I know a thing or two about literature research, which has led me to take certain steps. Fortunately, there’s more & better info available now (like your excellent site), so my quest would be easier. I’m obviously some type of sub-type PD, unusual in 2 ways: I had a huge tremor (eliminated with STN DBS 2 years ago) but not many other obvious symptoms, and Sinemet & other meds did little to nothing to improve my tremor or other symptoms (though bad side effects from meds). Yet I didn’t have a PD+ condition that made me do worse than others. In fact, I did better: slow progression, good cognition, independent, active, no dyskinesia. DBS fixed tremor, but gave me serious new symptoms. Areas of interest that I wish would be further explored: identify different types of PD & preferred treatments for each type; hormones: would hormonal treatments help some types of PD? (more men than women get PD & tend to fare worse; per my own observation, do more women get PD who have had no children and/or had infertility hormonal treatments or hysterectomy?); stress & trauma effect, esp. in early childhood; gut problems; why DBS improves some symptoms but causes others & how to prevent this. I won’t go into why I wonder about these things, but they are all based on something. Thanks again for your excellent post. Years ago I stood up in a PD meeting & suggested that perhaps PD should be considered a collection of syndromes not a disease, but was summarily dismissed by the neurologist speaker & audience.

LikeLike

Hi Pauline,

Thank you for your comment – there is a lot of food for thought here and it will take me a while to sort through it. There are certainly some topics there for future posts (particularly hormones). I am shocked by the response you got from the neurologist speaker at the PD meeting, particularly now as there is a growing consensus that we are dealing with a syndrome. I’m sorry your previous comment did not appear. I have looked in the backroom of the website and not found any quarantined comments there, so I’m not sure what happened there. Sorry.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Looking forward to your post on hormones. Estrogen patch was one of those steps I took. Perhaps a clue about the clueless neurologist was that this happened years ago before “syndrome” was popular. I was apparently way ahead of my time!

Pauline

LikeLike

Simon,

Yet another excellent article.

I would add just three points:

I would learn as much as possible about existing therapies. So much depends on having the right drug regimen. Seeing your doctor once every 6 months, which is typical in UK, is unlikely to lead to an optimal regimen. You need to work on this yourself.

I would take a punt on a therapy that was safe and that had good research findings, but had not been through a full clinical trial. Not only might this have efficacy, it would also have a placebo effect. I call this a “therebo” (THERapy or placEBO).

PD is slowly progressing, but not slowly enough. This allows you to build up a large amount of knowledge about the disease.

John

LikeLike

Hi John,

Thanks for the comment – I hope all is well.

What you say is very true: learning as much as one can about the available therapies is key. I guess I overlooked that. A slight blind spot on my part. And I also agree regarding the need to be proactive (I wonder how much Parkinson’s-associated apathy is at play here in some cases).

As for taking a punt, that would depend entirely on what one learns about oneself. For example, if I discovered that I have a PARKIN mutation, I would certainly not focus on immunotherapies against alpha synuclein. It has to be an educated punt, and that is where knowing thyself comes before knowing thy enemy.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon

A reallly thought provoking article. Thank you. Keith

LikeLike

Thanks Keith – you are very welcome

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon,

As you know, NAC has some interesting evidence of efficacy including a couple small double-blind trials and some intriguing imaging results. I would (and do) incorporate NAC. Thanks so much for SoPD. My go-to source.

Bill

LikeLiked by 1 person

What do I do? – I read and read….the science. From that I doubt there will ever be a single intervention for idiopathic PD, too many pathogenic feedbacks for that. And I am fortunate in being able to avoid raising dopamine with drugs, the tremor is tolerable. My DIY approach involves a cocktail of endogenous agents. One success, now in its third year, was combining vitamin D3 with NAC and resveratrol and abolisihng leg and foot cramping, ( NAC and Resv now discontinued as most of their function is covered by D3). A new addition to the cocktail is ergothioneine., a mito-targeted anti-oxidant Its a personal experiment, with of course a huge placebo effect.

Peter

LikeLike

Fantastic article Simon.

Question: why do you not give greater importance to the exercise study that showed de novo patients stopping their progression by running on a treadmill?

The complimentary research unrelated to Parkinson’s makes that finding almost expected. To me it is the single most important change someone with a neurological disorder can make, although I realize that a great many patients are simply beyond the point where such a regimen is possible.

LikeLike

Hi Joe,

Thanks for the comment – I hope all is well.

While I think some sort of exercise (and stretching) should be a foundation block of any treatment effort, I am reluctant to encourage folks to go the whole hog. And my concern is the inflammatory issue that could be potentially at work in the younger onset/genetic variant cases. I discuss this in the last post I wrote on exercise research (https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2018/09/20/exercise/). Until we have more information, I think folks should simply do what their bodies are telling them feels good/right.

Does this answer the question?

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLiked by 1 person