|

Today saw the publication of one of my favourite stories of Parkinson’s research. It is a tale of courage, serendipity, hard work, and (most importantly) an idea for a research project that came from the Parkinson’s community, but has now opened new doors for researchers and could have important implications for everyone. In 2012, former nurse Joy Milne was attending a Parkinson’s support group meeting in Edinburgh (Scotland) when she bravely asked the scientist presenting research that day, “Do people with Parkinson’s smell different?” What happened next is likely to become that stuff of legend. In today’s post, we will discuss the back story, review a new research report investigating the smell of Parkinson’s, and consider what the results could mean for the Parkinson’s community.

|

Erasto Mpemba & Denis Osborne. Source: Rekordata

Erasto Mpemba & Denis Osborne. Source: Rekordata

In 1963, Dr. Denis G. Osborne – from the University College in Dar es Salaam – was invited to give a lecture on physics to the students at Magamba Secondary School (Tanganyika, Tanzania). At the end of his lecture, a 13 year old student, named Erasto Mpemba, stood up and asked Dr Osbrone:

“If you take two similar containers with equal volumes of water, one at 35 °C (95 °F) and the other at 100 °C (212 °F), and put them into a freezer, the one that started at 100 °C (212 °F) freezes first. Why?”

The question was met by ridicule from his fellow classmates.

But to his credit, Dr Osborne went back to his lab and conducted some experiments based on the question, confirming Mpemba’s observation. Together they published the results in 1969, and the phenomenon (the process in which hot water can freeze faster than cold water) is now referred to as the Mpemba effect.

Mpemba effect. Source: Wikipedia

Mpemba effect. Source: Wikipedia

The point is: All scientific discoveries start with an observation, followed by an experiment.

And scientists do not have a monopoly on this.

There have been many cases of ‘laypeople’ – like Erasto Mpemba – making important observations. And recently the Parkinson’s world had a perfect example of this. It’s very own Erasto Mpemba moment.

What are you talking about?

Dr Les Milne. Source: BBC

Dr Les Milne. Source: BBC

Dr Les Milne was a consultant anaesthesiologist at Macclesfield in Cheshire for 25 years. He was one of the first medical directors in the Mersey region, at one point having five departments under his management. He was instrumental in changing the training of theatre operating assistants in the hospital, even giving up his own time to provide extra training in maths and English to trainees to help them get the qualification required. His was an impressive career.

In the mid 1980s, Les’s wife, Joy Milne, began noticing a change in his body smell. It was a “sort of woody, musky odour” Joy suggested, and she “started suggesting tactfully to him that he wasn’t showering enough or cleaning his teeth. He clearly didn’t smell it and was quite adamant that he was washing properly.” (Source).

Joy Milne. Source: Telegraph

Joy Milne. Source: Telegraph

Joy, a former nurse, let the matter go, but as you shall see this simple observation was to have important ramification later on in this story.

In 1996, at 45 years of age, Les was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s. And five years later, he retired and the couple decided to move back to Scotland, and they settled in Perth. They dealt with the condition for the next decade, and it wasn’t until Joy attended a Parkinson’s UK awareness lecture in 2012 that the observation about the body odour really hit home.

The event was held on the 19th April, and a young Parkinson’s UK Senior Research Fellow named Dr Tilo Kunath was presenting his research (Dr Kunath has made a previous appearance on the SoPD – click here to read that post).

Dr Tilo Kunath. Source: MRC

Dr Tilo Kunath. Source: MRC

At the end of his presentation – in a scene reminiscent of Erasto Mpemba’s case – Joy asked “why do people with Parkinson’s smell different”

Tilo assumed that the question had been mis-worded and referred to the loss of one’s sense of smell, so he pointed out that “Parkinson’s sufferers often lose their sense of smell“.

But Joy clarified that she was actually asking about body odour, which took Tilo by complete surprise.

And similar to the case of Erasto Mpemba – to his credit, Dr Kunath decided to investigate the matter. He tracked down Joy and proposed to do a test. They recruited six people with Parkinson’s and six people without the condition, and asked them to wear a t-shirt for 24 hours (sleeping in them as well). The scientists then collected the t-shirts, bagged them and coded them, noting down who was who. They then asked Joy to blindly smell each shirt and tell them who had Parkinson’s and who didn’t. Joy was unaware before hand who wore which shirt.

Dr Kunath bagging t-shirts. Source: BBC

Dr Kunath bagging t-shirts. Source: BBC

The shirts were divided into two and each piece was given its own bag – hence the reason for some many samples in the image below). The smell test session lasted 2 hours according to Dr Kunath, and Joy’s nose became sore and inflammed.

But the outcome was worth it.

Joy correctly guessed 11 out of the 12 participants. That is to say, she correctly identified all of the six people with Parkinson’s as having Parkinson’s, and she got 5/6 correct for the control group – a rather impressive feat I think you will agree!

Joy was also adamant that the one ‘control’ subject that she got wrong, also had Parkinson’s. But according to the individual in question and the doctors running the test, the subject did not have Parkinson’s.

But then, eight months later, that same subject (highlighted in yellow in the table above) informed the scientists that he had just been diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

This small experiment got the attention of Parkinson’s UK and the Michael J Fox Foundation and researchers began designing a study that would help to identify exactly what Joy was smelling.

The follow up study was conducted by Professor Perdita Barran and colleagues at the University of Manchester.

Joy & Professor Barran. Source: Manchester

And the results of that study were published today:

Title: Discovery of Volatile Biomarkers of Parkinson’s Disease from Sebum

Title: Discovery of Volatile Biomarkers of Parkinson’s Disease from Sebum

Authors: Trivedi DK, Sinclair E, Xu Y, Sarkar D, Walton-Doyle C, Liscio C, Banks P, Milne J, Silverdale M, Kunath T, Goodacre R, Barran P

Journal: ACS Cent. Sci., Article ASAP

PMID: N/A (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

This study was divided into three stages. The first two stages (discovery and validation) involved samples from 61 people – this group involved a mix of control subjects, people with Parkinson’s on medication, and people with Parkinson’s not on medication (drug naïve). The first stage (involving 30 participants) focused on for volatilome discovery, and the second stage (involving 31 participants) was used to validate the results of the first stage.

Hang on a second. What does volatilome discovery mean?

The chemical compounds that the study was focused on are called “Volatile Organic Compounds” (or VOCs).

Source: Rabbitair

Source: Rabbitair

These are organic (meaning derived from living matter) chemicals that have a high vapour pressure at ordinary room temperature. They are numerous (there are thousands of them), varied, and ubiquitous (they are all around you).

Most scents and odours you smell are VOCs.

Volatilome discovery involves determining all of the VOCs (and also inorganic compounds) that originate from a sample being analysed.

The third cohort that the researcher used included three drug naïve people with Parkinson’s. They were used for smell analysis from Joy. Thus, in all 64 individuals were recruited to the study (21 controls and 43 people with Parkinson’s).

Each sampling from all of the individuals involves in the study involved swabbing the upper back with a medical gauze.

Why the upper back?

The early test with T-shirts indicated the odour was present in areas of high sebum production – the upper back and forehead, but not the armpits.

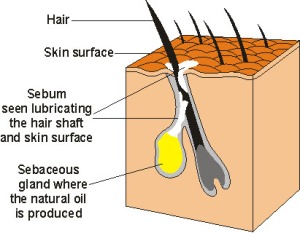

What is Sebum?

Sebum is an oily/waxy matter that our skins secretes. It lubricates and waterproofs the skin and hair of mammals.

Sebum excretion in the skin. Source: Hair Articles

The researchers suspected that sebum may be the source of the “Parkinson’s odour”.

Why did they think that?

The idea relates to a common feature of Parkinson’s that doesn’t get much attention today.

When the original results of Joy Milne’s experiment were anounced, Prof Anthony Lang (at the University of Toronto) pointed out that “one feature of Parkinson’s that we don’t see much of in the era of levodopa treatment is seborrhea. This feature might be related to some metabolite secreted by the glands in the skin” (Source).

What is seborrhea?

Seborrhea is a common inflammatory skin problem, characterised by the accumulation of scales and greasy skin. It causes a red, itchy rash and white scales.

Seborrhea. Source: Beautypedia

Seborrhea has been associated with Parkinson’s, occurring in as many as 50-60% cases (Click here to read more about this). It was also a feature of the condition that noted very early in the research of Parkinson’s:

Title: The seborrhoeic facies as a manifestation of post-encephalitic Parkinsonism and allied disorders.

Title: The seborrhoeic facies as a manifestation of post-encephalitic Parkinsonism and allied disorders.

Author: Krestin D.

Journal: QJM. 1927; 21(81):177–186.

PMID: N/A

More recently, researchers have proposed that Seborrhea (or seborrheic dermatitis) may represent an early premotor feature of Parkinson’s (resulting from autonomic nervous system dysregulation), and it could be used as an early biomarker of the condition (Click here to read more about this).

Sebum secretion is increased in individuals affected by Parkinson’s, and as – Prof Lang noted above – treatment with L-dopa has been shown to reduce sebum secretion (Click here to read more about this).

Interesting. So what did the researchers find in their new study?

The researchers identified 17 candidate compounds, 9 of which were present in both the discovery and validation cohorts, and 4 of which differential present in specific directions between the Parkinson’s and control samples. This provided the researchers with a very distinct combination of VOCs-associated with Parkinson’s, including significantly altered levels of perillic aldehyde (reduced levels) and eicosane (increased levels). This ‘signature’ provided a smell that Joy described as being highly similar to the smell of Parkinson’s. Joy was able to detect a whole range of concentrations offered to her of these compounds.

Interestingly, there were no significant differences found between people with Parkinson’s on medication and those who were drug naïve (indicating that treatment byproducts are not being picked up in the sebum).

The investigators acknowledge that the study was limited by small sample size, but the results are still very interesting and provide support for justifying larger studies that could assess longitudinal changes in odour. It would also be critical for future studies to include some individuals with other neurodegenerative conditions (such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s) to be sure that the smell is specific to Parkinson’s. Does Alzheimer’s have a smell?

How could this change in smell be occuring?

The simple answer at the moment is we have no idea.

But recently, there have been a series of reports that suggest that particular forms of alpha synuclein – the protein associated with Parkinson’s – are present in the nerves lining the skin in people with Parkinson’s (Click here, here, here, & here to read more about that). It may be that disrupted activity in these nerves could be affecting the secretion of sebum.

Another possibility is that gradual reductions in proteins in the brain (such as norepinephrine) could be affecting levels of other proteins that influence skin regulation. In the absence of norepinephrine, for example, levels of another protein called α–Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (or just α-MSH) increase significantly. Norepinephrine keeps α-MSH levels under control, but in Parkinson’s – where norepinephrine is reduced – α-MSH levels begin to increase, which in turn increase sebum secretion (Click here to read more about this).

This image provided by Adrian Wilder-Smith & Dr Kunath demonstrates possible mechanisms underlying the increase in sebum secretion.

Source: Adrian Wilder-Smith & Tilo Kunath

Source: Adrian Wilder-Smith & Tilo Kunath

But how is this new research actually useful?

The findings open doors to a number of new possibilities.

For example, there are efforts underway to teach dogs to smell Parkinson’s. Manchester University and the research charity Medical Detection Dogs are working on this:

In addition, it would be very interesting to start including smell detection tests in research surrounding early “prodromal” cohorts. These are individuals who do not have Parkinson’s, but are displaying some of the early warning signals of the condition (such as REM sleep behaviour disorder, loss of a sense of smell, constipation, etc). Could an odour test provide a better indication as to which individuals will go on to develop Parkinson’s?

But what is the point of early detection if we do not have any therapies to help people who may go on to develop Parkinson’s?

It is a hard question to answer, but the idea of early detection and beginning clinical trials of experimental disease modifying therapies before individuals have been diagnosed is very appealling. Such an approach will hopefully lead to better quality of life for the individuals in question, and less of a need for health services.

In addition, as Dr Beckie Port from Parkinson’s UK points out in the video above, better diagnostic methods/tests would help to remove some of the pre-diagnosis stress and anxiety that people go through as they wonder what is wrong.

But what about individuals who already have Parkinson’s?

This new odour research could also lead to a new method of monitoring the condition over time. Larger, longitudinal studies will be required before we will have any clarity on this, but it is an interesting possibility.

So what does it all mean?

A lady in the community had the courage to ask an odd question (odd for the rest of us at least) – does Parkinson’s have a specific odour? A researcher had the couriousity to follow up the question with a small, basic pilot study. And then others in the community – both researchers and people with the condition – engaged all the way through to the publication of this new report today. It is just such an inspiring tale.

I really love this story.

Without the intial insight from a member of the community, researchers may never have considered what Parkinson’s smells like? (it kinda beg the question what other aspects of Parkinson’s are we missing/not considering? For example, what does Parkinson’s sound like?). It represents a fantastic example of engagement by everyone involved.

One that I’d love to see replicated on other features of the condition.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The author of this post would like to extend special thanks to Dr Tilo Kunath for providing material and information used to generate the post.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Telegraph

This smell as Non-precise and inaccurate (with many variables) method. and “Unnecessary Stress” for the public even when used as prescreening

LikeLike

Hi iscatmen,

Thanks for your comment. You are that any smell test (or any early biomarker) will need to be 100% accurate before it can be utilised in any effective way. And even then, how? Who has that right? In a hypothetical world, such discussions are just hypothetical. But in a world with Joy Milne and Parkinson’s smelling dogs, not so hypothetical. Perhaps we should start a discussion with a genetic counsellor who deals with Huntington’s disease to outline how such situations can be handled.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

For a year or two before my diagnosis of Parkinson’s I also noticed that I smelled different, disturbingly so. Yes, a musky smell. I can’t smell it now, but that could be my anosmia. I’m a 67 year old woman, tremor predominant Parkinson’s Disease for 4 years.

LikeLike

Hi Mary,

Thanks for your comment and for sharing. In Parkinson’s clinics, after the initial story of Joy came out, I remember many partners coming forward and saying that they smelt something different in their spouse before or soon after diagnosis. I have to be honest and say that the vast majority of the partners were women. That – and your statement here – made me wonder if women have a better sense of smell – and there is actually research to suggest it ( https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0111733 ). It would be interesting to find out if any other females with Parkinson’s smelt a difference about themselves before diagnosis.

Thanks again for the interesting comment.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Thanks Simon for another interesting article.

I went through a pre-diagnosis stage of my wife telling me that I had a fungal smell and fungal skin. The feel of Parkinson’s?

You mention the sound of Parkinson’s, Max Little et al. at the Parkinson’s Voice Initiative have done a lot of work on this:

http://www.parkinsonsvoice.org/team.php

Given that PD affects the whole body, I would expect it to leave a lot of signs in its wake. New techniques of detecting signs should come thick and fast on the back of improved electronic sensors and machine learning apps. The challenge, as I see it, is to speed up the clinical trial process required to validate these tests.

John

LikeLike

Hi,

I would like to comment on the above question “But what is the point of early detection if we do not have any therapies to help people who may go on to develop Parkinson’s?”

I understand that researchers are very interested in developing tests that allow Parkinson’s to be diagnosed as early as possible. There is a lot of research in this area and sometimes there is some vague talking about possible benefits that an early diagnosis could have for those affected.

In my opinion, however, the possible disadvantages of an early diagnosis for PwPs are discussed far too little. If I had received my diagnosis not in my mid-forties, but in my mid-twenties, as it might have been possible with today’s or tomorrow’s knowledge, then in my opinion the disadvantages for me would have far outweighed the advantages of an early diagnosis. Most likely, I would not have got the job that I (still) have now, nor the health insurance, nor the disability insurance, nor the long-term care insurance. Problems with finding a partner could also have been possible. I do not see any therapies within reach that could possibly compensate for such disadvantages from the point of view of a PwP.

zz

LikeLike

Hi Simon,

Thank you for this lovely article.

Not only an interesting story, this would also make a good teaching tool – an accessible example of a controlled study. A basic knowledge of statistics suddenly becomes important if you want to learn about Parkinson’s, and I sometimes feel when reading (even patient focussed) research articles that there is a lot of assumed knowledge in statistics, and, well, we are not born knowing these things. (In my case, no excuse – I did stats 101 at uni and wish I’d listened harder). For anyone who needed to learn like I did, I found Nathan Green’s ‘S-series’ in the Guardian very helpful. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/dec/02/statistics-series

Regards,

Paula

LikeLike

Great post! And props to Tilo for tracking Joy down.

I’d pay this lady to smell every person in the waiting room of the neurology department for a year… would be curious what she keyed off with respect to age of offset, subtype, known genetic markers, etc! Give her a notebook, look for the patterns, then validate with the test equipment.

Also, I’m super jealous of the individual 12 years in who’s still drug naive. They should be studied also.

LikeLike

In response to what other aspects of Parkinson’s are we missing / not considering, here is my “Mpemba moment” – amalgam fillings, which are around 50% composed of the highly neuro toxic element mercury.

According to sources, Ingestion of elemental mercury causes a wide variety of cognitive, personality, sensory, and motor disturbances. The most prominent symptoms include tremors (initially affecting the hands and sometimes spreading to other parts of the body), irritability, insomnia, memory loss, neuromuscular changes (weakness, muscle atrophy, muscle twitching), headaches, polyneuropathy, hyperactive tendon reflexes, slowed sensory and motor nerve conduction velocities), and performance deficits in tests of cognitive function.

Sound familiar?

Controversy over the mercury component of dental amalgam dates back to its inception.

Scientists agree that dental fillings leach mercury into the mouth on a 24x7x365 basis, yet the use of mercury in dental fillings is approved in most countries. Norway, Denmark, and Sweden have since banned the use of mercury in dental amalgams following a 2002 report by the 1991 Chair of the World Health Organization Task Group on Environmental Health Criteria for Inorganic Mercury.

The report concluded: “With reference to the fact that mercury is a multipotent toxin with effects on several levels of the biochemical dynamics of the cell, amalgam must be considered to be an unsuitable material for dental restoration”

Is further study, including a comprehensive epidemiological investigation, long overdue?

LikeLike

Thank you for another great post – I look forward to each and every one and see each as another sliver of hope.

My question is – is there a SHAPE to Parkinsons? Based on your previous post about evolution and brain size are people with big heads predisposed to Parkinsons?

LikeLike