Did you know that human saliva is 99.5% water?

But a recent set of studies have suggested that the remaining 0.5% holds some interesting insights into Parkinson’s disease.

Interesting fact about saliva – while there is a lot of debate as to how much saliva we produce on a daily basis (anywhere between 0.75 to 1.5 litres per day), it is generally accepted that during sleep the amount of saliva produced drops to almost nothing. Why? Big shrug.

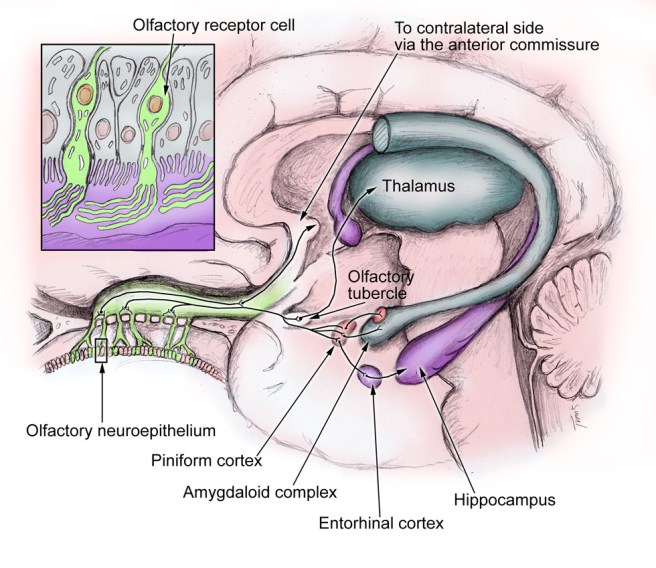

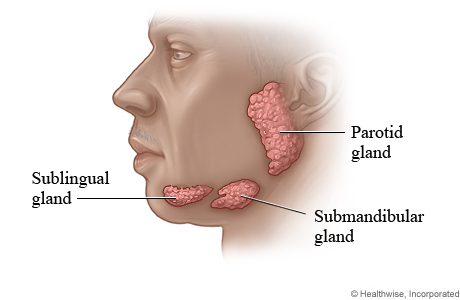

Saliva is a solution produced by three main sets of glands in our mouth: the parotid, Sublingual, and Submandibular glands:

The human salivary glands. Source: WebMD

The solution produced serves several important functions, namely:

- beginning the process of digestion by breaking down food particles.

- protecting teeth from bacterial decay.

- Moisturising food to aid in the initiation of swallowing.

As we mentioned above, 99.5% of saliva is water. The remaining 0.5% is made up of enzymes and antimicrobial agents. There is also a number of cells in each millilitre of saliva (as many as 8 million human and 500 million bacterial cells per millilitre).

By analysing those human cells, scientists can learn a lot about a person. For example, they can conduct genetic analysis and determine if a person has a particular mutation.

So what has this got to do with Parkinson’s disease?

Well, recently several research groups have been looking at saliva with the hope that biomarkers – chemicals that may allow for early detection or better monitoring of Parkinson’s disease – could be found.

And recently, some of that research has seemingly paid big dividends:

Title: Prevalence of Submandibular Gland Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s Disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies and other Lewy Body Disorders.

Authors: Beach TG, Adler CH, Serrano G, Sue LI, Walker DG, Dugger BN, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Caviness JN, Intorcia A, Filon J, Scott S, Garcia A, Hoffman B, Belden CM, Davis KJ, Sabbagh MN.

Journal: J Parkinsons Dis. 2016 [Epub ahead of print]

PMID: 26756744

In this study, published in January of this year, the researchers collected small biopsies of the submandibular gland (one of the three primary producers of saliva) from the bodies of people who died with various conditions (including Parkinson’s disease). They analysed the biopsies for alpha synuclein – the chemical in the brain associated with Parkinson’s disease. We have previously written about alpha synuclein, a chemical in the brain that is associated with Parkinson’s disease (for a primer on alpha synuclein, click here). They found that alpha synuclein was present in the saliva gland of 89% of the subjects who died with Parkinson’s disease, but none of the 110 control samples.

This result led the same research groups to attempt a similar study on live subjects and they published the results of that study in February of this year:

Title: Peripheral Synucleinopathy in Early Parkinson’s Disease: Submandibular Gland Needle Biopsy Findings.

Authors: Adler CH, Dugger BN, Hentz JG, Hinni ML, Lott DG, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta S, Serrano G, Sue LI, Duffy A, Intorcia A, Filon J, Pullen J, Walker DG, Beach TG.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2016 Feb;31(2):250-6.

PMID: 26799362

The researchers enrolled 25 people with early-stage Parkinson’s disease (less than 5 years since diagnosis) and 10 control subjects. All of these subjects underwent a small biopsy of the submandibular gland. Those biopsies were then analysed for alpha synuclein and the researchers found that 74% of the Parkinsonian biopsies and 22% control biopsies had alpha synuclein present in the submandibular gland.

And remarkably, this report was followed up this last week by a group in Italy, who published some very interesting data:

Title: Abnormal Salivary Total and Oligomeric Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease.

Authors: Vivacqua G, Latorre A, Suppa A, Nardi M, Pietracupa S, Mancinelli R, Fabbrini G, Colosimo C, Gaudio E, Berardelli A.

Journal: PLoS One. 2016 Mar 24;11(3):e0151156.

PMID: 27011009 (this report is OPEN-ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers collected salivary samples – actual spit – from 60 people with Parkinson’s disease and 40 age/sex matched control subjects. They then measured the saliva for different types of alpha synuclein. In this study, the researchers measured both the total amount of alpha synuclein in the saliva and also special forms of alpha synuclein.

Alpha synuclein initially starts out in the brain in a monomeric form – as a single version of alpha synuclein. This form of alpha synuclein is believed to be safe. A more mature form of alpha synuclein, called oligomeric, is believed to be the seed of the aggregations found in the Parkinsonian brain, Lewy bodies.

Curiously, in this study the researchers found that the total amount of alpha synuclein in the salivary of people with Parkinson’s disease was lower than that of the control subjects. But – and it’s a big ‘but’ – the amount of alpha synuclein oligomers was higher in the people with Parkinson’s disease than normal healthy controls.

The researchers proposed that the decreased concentration of total alpha-synuclein may reflect the formation of lewy bodies in the brain, and that this test might help the early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease.

Here at the Science of Parkinson’s we are approaching this research cautiously. Previous attempts at measuring saliva in Parkinson’s disease have not had such significant results when comparing people with Parkinson’s disease and controls (click here for more about that study). The need for better biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease provides the reasons for this research, but the variability between the results different groups are getting leaves one wondering about the viability of the approach. It would indeed make for a very easy, non-invasive testing platform for Parkinson’s disease (‘Please spit into this tube for me’), but more research is needed before it can be applied on the large scale.

We’ll keep watching and hoping.