Donating blood helps to save lives. And an awful lot of blood is needed on a daily basis: In the England alone, over 6,000 blood donations are required every day to treat patients.

There has been concerns over the years about what can be transmitted via blood donation (from donor to recipient). The good news is that we now know that Parkinson’s disease is not.

Today’s post looks at recent research investigating this issue and discusses the implications of the findings.

Blood transfusions save lifes. Source: New York Times

The average adult human carries approx. 10 pints (about 6 litres) of blood in his body. So much blood, that we actually have an excess – we can survive with a little less. And this allows us to donate blood to blood banks on a regular basis (approx. every 8 weeks). Roughly 1 pint can be given during each blood donation and our bodies will have no trouble replacing it all.

These donations can be used in blood transfusions, replacing blood that has been lost via accident or during surgical procedures. It may surprise you that blood transfusion (from human to human) has been practised for some time. The very first blood transfusion was performed by an obstetrician named Dr. James Blundell in the late 1820’s.

Dr. James Blundell. Source: Wikpedia

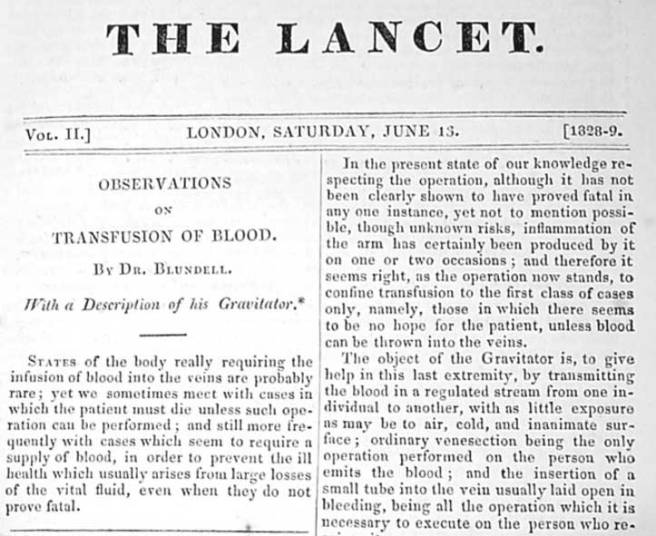

The exact date of that first procedure is the subject of debate, but Blundell wrote up his experience in the journal Lancet in 1829:

Blundell’s article in the journal Lancet. Source: Wikipedia

Since that time, blood transfusions have gradually become an everyday occurrence at hospitals all over the world. And as we suggested above a lot of blood is used on a daily basis, keeping people alive. Determining whether each donation of blood is safe to use is obviously a critical step in this process, and all donated blood is tested for HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis and other infectious diseases before it is released to hospitals. But for a long time there has been a lingering concern that not everything is being detected and filtered out.

In fact there has been a serious concern that some neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease may be transmissible. If these diseases are being caused by ‘prion-like behaviour’ from the particular proteins involved with these conditions (eg. beta amyloid and alpha synuclein, respectively), then there is a very real possibility that such rogue proteins could be transferred via blood transfusions.

This was a concern (note the past tense) until July of this year when this research report was published (with a rather mis-leading title):

Title: Transmission of neurodegenerative disorders through blood transfusion. A cohort study

Authors: Edgren G, Hjalgrim H, Rostgaard K, Lambert P, Wikman A, Norda R, Titlestad KE, Erikstrup C, Ullum H, Melbye M, Busch MP, Nyrén O.

Journal: Ann Intern Med. 2016 Sep 6;165(5):316-24.

PMID: 27368068

The researchers in this study took all of the data from the enormous nationwide registers of blood transfusions in Sweden and Denmark – collectively almost 1.5 million people have received transfusions in these two countries between 1968 and 2012 – and compared the medical records of the recipients to those of the donors (you have to love the Scandinavians for the medical databases!). Approximately 3% of the recipients received a blood transfusion from a donor who was diagnosed with one of the neurodegenerative diseases included in this study (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Motor neurone disease (or Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – ALS). There was absolutely no evidence of transmission of any of these diseases.

For the statistic lovers amongst you, the hazard ratio for dementia in recipients of blood from donors with dementia versus recipients of blood from healthy donors was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.99 to 1.09). Estimates for individual diseases, Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease were 0.99 (CI, 0.85 to 1.15) and 0.94 (CI, 0.78 to 1.14), respectively.

These statistics mean that if Parkinson’s disease is being transmitted via a blood transfusion, it is an extremely rare event.

So what does this mean for our understanding of Parkinson’s disease?

Well, we already know that you can’t catch Parkinson’s disease from your spouse (Click here to read more on this) and there is a lot of other evidence to suggest that Parkinson’s disease is not contagious (Click here to read more on this). So this is one less thing for carers, family members and friends to worry about.

But if Parkinson’s disease is not caused by some contagious agent, this knowledge has major implications for our understanding of the disease. Previous lab-based research has pointed toward a ‘Prion’-like nature to alpha synuclein (the protein most associated with Parkinson’s disease. Prions being small infectious agents made up entirely of protein material, that can lead to disease that is similar to viral infection. And researchers actually found that if you inject specific types of alpha synuclein into the muscles of mice, those animals would start to develop cell loss in the brain (Click here to read more about this).

If Parkinson’s disease is a ‘prion’ condition, then we have to ask one important question: why isn’t it being transmitted via blood transfusion? Alpha synuclein is certainly found in the blood of people with Parkinson’s disease.

It could be that an infectious agent initiated the condition many years ago and it has very slowly been developing (similar to chronic infections resulting from Hepatitis – click here to read more on this).

Research like we have reviewed today may result in a serious re-think of our theory of Parkinson’s disease.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from CampusCluj