Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease is actually hard work, and mistakes can be made (click here for more on this). A new criteria has been proposed by a group of experts. In today’s post we will have a look at what is included (and excluded) from this new criteria for Parkinson’s disease.

Brain imaging of a normal brain (left) and two Parkinsonian brains. Source: the Lancet

In the United Kingdom, the most commonly used criteria for Parkinson’s disease is the UK Brain bank criteria. It is a three step criteria that clinicians can use in their assessments of individuals suspected of having Parkinson’s disease.

The UK Brain bank criteria. Source: Scielo

In the USA, many physicians use the United Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) for diagnosing Parkinson’s disease. UPDRS is a rating scale of Parkinson’s features. There is also a growing trend towards the use of a brain imaging technique called a DAT-Scan, which is an FDA-approved approach for differentiating Parkinson’s disease from essential tremor (but it cannot distinguish between PD and parkinsonian subtypes).

DAT-Scan. Source: GEHealthcare

Ok, so why do we need a new criteria from Parkinson’s disease?

There have been major advances made since Dr James Parkinson first described Parkinson’s disease in 1817 (200 year anniversary coming up!!!). All that progress is changing in the way we look at the condition, for example only in the last two decades has our understanding of the genetics underlying Parkinson’s really started to blossom.

Scientific advances have also complicated our view of Parkinson’s disease. To date, a definitive diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease can only be made at the postmortem stage, with an analysis of the brain itself. That examination involves looking for clusters of proteins in the brain, called Lewy bodies. Recently, however, it has been observed that many people with Parkinson’s disease that have a mutation in the Lrrk2 gene do not have Lewy bodies. Why this is? We do not know. It is one of many complicating factors in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease.

Given this state of affairs, it was decided that an updated definition/criteria for Parkinson’s disease was required.

Who decides what is Parkinson’s disease?

In 2014, the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) organised a task force with the goal of providing an updated definition/criteria for Parkinson’s disease.

That group of experts held two ‘brainstorming’ teleconferences and then a physical meeting that all attended. From those meetings a first draft document was produced. Over the next 6 months a revision process was undertaken. The final version of the new criteria was ratified in San Diego (California) in June 2015.

What is the new criteria?

If you would like to read the new criteria in full – you can find it by clicking here.

Below we present a layman summary of the criteria. Central to the new criteria is firstly establishing that an individual has Parkinsonism, and then determining if Parkinson’s disease is the cause of that Parkinsonism.

Now that sounds a bit weird, but it does make sense. Here is how it works: Parkinsonism embodies a set of conditions that are characterized by tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. Parkinson’s disease is the most common type of parkinsonism. Another form of Parkinsonism is vascular parkinsonism, in which blood vessel issues cause the tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity features. Approximately 7% of people who are diagnosed with parkinsonism have developed their features after using (or treatment with) particular medications (such as neuroleptic antipsychotics). Thus, it is important to determine that a person’s parkinsonism is caused by Parkinson’s disease itself.

How do you establish Parkinsonism?

Ever since Dr James Parkinson’s first description of Parkinson’s disease, the clinical criteria for the parkinsonism have centred around the motor features. The new criteria continues this tradition, defining of Parkinsonism being based on the three cardinal motor features. These are:

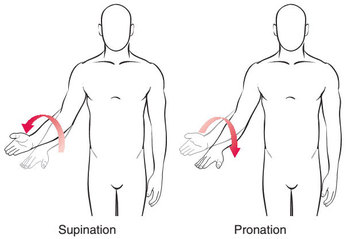

Bradykinesia, which is defined as slowness of movement AND decrement in amplitude or speed as movements are continued (eg. progressive hesitations/halts). Bradykinesia can be evaluated by using finger tapping, hand movements, pronation-supination movements (for example, twisting the forearm so that the palm is facing up and then down), toe tapping, and foot tapping.

Pronation-supination movements. Source: YogiDoc

Importantly: Although bradykinesia can also occur in the voice, the face, and axial or gait domains, limb bradykinesia must be documented to establish a diagnosis of Parkinsonism.

Rigidity – Rigidity is determined on the “slow passive movement of major joints with the patient in a relaxed position and the examiner manipulating the limbs and neck.”

Rigidity deals with resistance and is referred to as ‘Lead-pipe rigidity’. This occurs when an increase in muscle tone causes a sustained resistance to passive movement (without fluctuations) through an entire range of motion.

Cogwheel rigidity is a combination of lead-pipe rigidity and tremor, presenting as a jerky resistance to passive movement – caused by muscles tensing and relaxing. Cogwheel rigidity is often present in Parkinson’s disease, but without lead-pipe rigidity Cogwheeling does not fulfill minimum requirements for rigidity.

Resting Tremor – this involves the shaking of 4 to 6-Hz in a fully resting limb. Importantly, for diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, the tremor must be suppressed during movement initiation. The assessment of resting tremor can be made during the entire period of examination. And although postural instability is a feature of Parkinson’s disease, alone it does not qualify for a diagnosis of the condition.

Once it has been determined that the person has parkinsonism, the examiner will then determine whether the patient meets criteria for Parkinson’s disease as the cause of this parkinsonism. This determination is based on three requirements:

- Absence of absolute exclusion criteria

- At least two supportive criteria

- No red flags

1. Absolute Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria is a list of clinical aspects that indicate alternative possible causes of Parkinsonism. The presence of any of the following features will result in Parkinson’s disease being ruled out as the cause of the Parkinsonism:

– Indications of cerebellar abnormalities, such as cerebellar gait, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor abnormalities.

– Downward vertical supranuclear gaze palsy (difficulty looking down), or selective slowing of downward vertical eye movements

– Diagnosis of probable behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (BvFTD) or primary progressive aphasia (a rare neurological syndrome in which language capabilities become slowly and progressively impaired, while other mental functions remain preserved)

– The Parkinsonian motor features restricted to only the lower limbs for more than 3 years

– Treatment with any dopamine receptor blockers or dopamine-depleting agents in doses and a time-course consistent with drug-induced parkinsonism

– The absence of any observable response to a high-dose of levodopa

– Unequivocal cortical sensory loss (eg., graphesthesia or the ability to recognize writing on the skin purely by the sensation of touch), clear limb ideomotor apraxia, or progressive aphasia

– Normal functional neuroimaging of the presynaptic dopaminergic system (this could be the DATScan mentioned above)

– Documentation of an alternative condition known to produce parkinsonism and plausibly connected to the patient’s symptoms

2. Supportive Criteria

The Supportive criteria is a list of clinical findings that support the indication that the Parkinsonism is caused by Parkinson’s disease. These include:

- An obvious beneficial response (return to normal or near-normal level of functioning) in response to dopaminergic therapy (L-dopa treatment)

- The presence of levodopa-induced dyskinesias

- Resting tremor of a limb, documented on clinical examination

- Positive results from at least one ancillary diagnostic test. Currently available tests that meet this criterion include:

- Olfactory loss (adjusted for age and sex)

- Metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy (say that three times really fast!)

3. Red Flags

Red flags are indications of an alternative explanation for the Parkinsonism. While the presence of red flags can be counterbalanced by supportive criteria items, if there are more than two red flags, clinically probable PD cannot be diagnosed. The red fags include:

- Rapid progression of gait impairment requiring regular use of wheelchair within 5 years of onset of features

- A complete absence of progression of motor symptoms or signs over 5 or more years unless stability is related to treatment

- Early bulbar dysfunction, defined as one of severe dysphonia, dysarthria (speech unintelligible most of the time), or severe dysphagia (requiring soft food, NG tube, or gastrostomy feeding) within the first 5 years of disease.

- Inspiratory respiratory dysfunction defined as either diurnal or nocturnal inspiratory stridor or frequent inspiratory sighs

- Severe autonomic failure in the first 5 y of disease. This can include Orthostatic hypotension or severe urinary incontinence or urinary retention in the first 5 years of disease.

- Recurrent (>1/y) falls because of impaired balance within 3 years of onset.

- The presence of disproportionate anterocollis (dystonic in nature) or contractures of hand or feet within the first 10 years.

- Absence of any of the common nonmotor features of disease despite 5 years disease duration. These include sleep dysfunction, constipation, daytime urinary urgency, Hyposmia, Psychiatric dysfunction (depression, anxiety, or hallucinations)

- Otherwise unexplained pyramidal tract signs, defined as pyramidal weakness or clear pathologic hyperreflexia (excluding mild reflex asymmetry in the more affected limb, and isolated extensor plantar response).

- Bilateral symmetric parkinsonism throughout the disease course. The patient or caregiver reports bilateral symptom onset with no side predominance, and no side predominance is observed on objective examination.

This new criteria for Parkinson’s disease will now be through a period of clinical evaluation and may be adjusted based on that assessment process.

It is interesting to see the condition becoming more defined and specified.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Help to buy SES