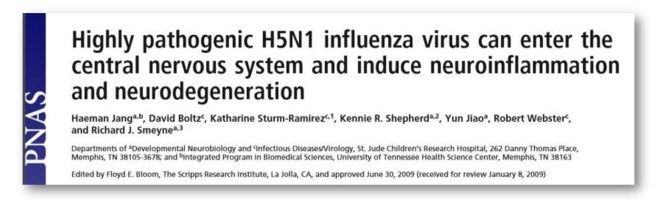

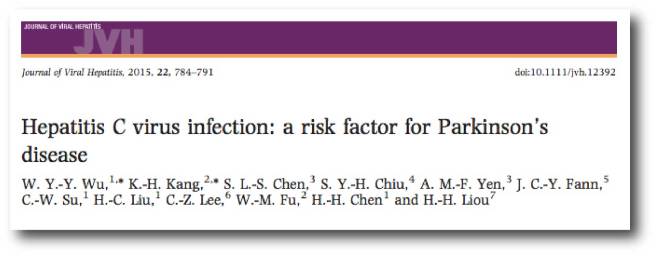

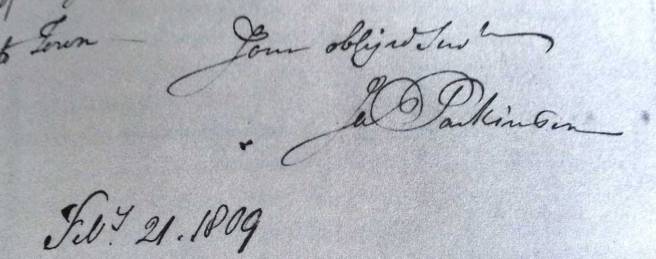

Last week scientists in Sweden published research demonstrating a method by which the supportive cells of the brain (called astrocytes) can be re-programmed into dopamine neurons… in the brain of a live animal!

It was a really impressive trick and it could have major implications for Parkinson’s disease.

In today’s post is a long read, but in it we will review the research leading up to the study, explain the science behind the impressive feat, and discuss where things go from here.

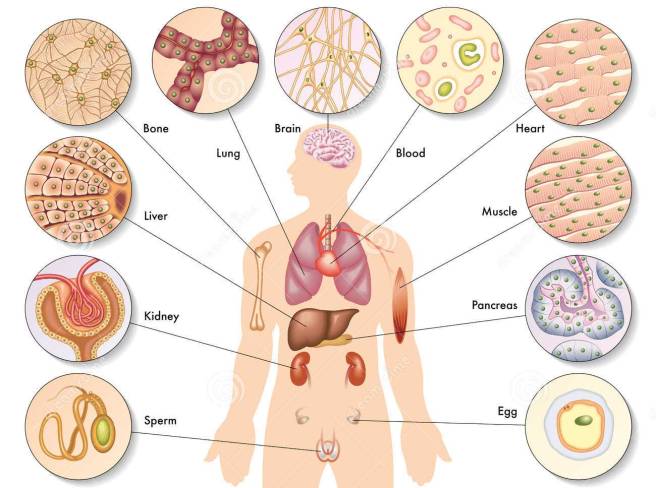

Different types of cells in the body. Source: Dreamstime

In your body at this present moment in time, there is approximately 40 trillion cells (Source).

The vast majority of those cells have developed into mature types of cell and they are undertaking very specific functions. Muscle cells, heart cells, brain cells – all working together in order to keep you vertical and ticking.

Now, once upon a time we believed that the maturation (or the more technical term: differentiation) of a cell was a one-way street. That is to say, once a cell became what it was destined to become, there was no going back. This was biological dogma.

Then a guy in Japan did something rather amazing.

Who is he and what did he do?

This is Prof Shinya Yamanaka:

Prof Shinya Yamanaka. Source: Glastone Institute

He’s a rockstar in the scientific research community.

Prof Yamanaka is the director of Center for induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Research and Application (CiRA); and a professor at the Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences at Kyoto University.

But more importantly, in 2006 he published a research report demonstrating how someone could take a skin cell and re-program it so that was now a stem cell – capable of becoming any kind of cell in the body.

Here’s the study:

Title: Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors.

Authors: Takahashi K, Yamanaka S.

Journal: Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):663-76.

PMID: 16904174 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

Shinya Yamanaka‘s team started with the hypothesis that genes which are important to the maintenance of embryonic stem cells (the cells that give rise to all cells in the body) might also be able to cause an embryonic state in mature adult cells. They selected twenty-four genes that had been previously identified as important in embryonic stem cells to test this idea. They used re-engineered retroviruses to deliver these genes to mouse skin cells. The retroviruses were emptied of all their disease causing properties, and could thus function as very efficient biological delivery systems.

The skin cells were engineered so that only cells in which reactivation of the embryonic stem cells-associated gene, Fbx15, would survive the testing process. If Fbx15 was not turned on in the cells, they would die. When the researchers infected the cells with all twenty-four embryonic stem cells genes, remarkably some of the cells survived and began to divide like stem cells.

In order to identify the genes necessary for the reprogramming, the researchers began removing one gene at a time from the pool of twenty-four. Through this process, they were able to narrow down the most effective genes to just four: Oct4, Sox2, cMyc, and Klf4, which became known as the Yamanaka factors.

This new type of cell is called an induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cell – ‘pluripotent’ meaning capable of any fate.

The discovery of IPS cells turned biological dogma on it’s head.

And in acknowledgement of this amazing bit of research, in 2012 Prof Yamanaka and Prof John Gurdon (University of Cambridge) were awarded the Nobel prize for Physiology and Medicine for the discovery that mature cells can be converted back to stem cells.

Prof Yamanaka and Prof Gurdon. Source: UCSF

Prof Gurdon achieved the feat in 1962 when he removed the nucleus of a fertilised frog egg cell and replaced it with the nucleus of a cell taken from a tadpole’s intestine. The modified egg cell then grew into an adult frog! This fascinating research proved that the mature cell still contained the genetic information needed to form all types of cells.

EDITOR’S NOTE: We do not want to be accused of taking anything away from Prof Gurdon’s contribution to this field (which was great!) by not mentioning his efforts here. For the sake of saving time and space, we are focusing on Prof Yamanaka’s research as it is more directly related to today’s post.

Making IPS cells. Source: learn.genetics

This amazing discovery has opened new doors for biological research and provided us with incredible opportunities for therapeutic treatments. For example, we can now take skins cells from a person with Parkinson’s disease and turn those cells into dopamine neurons which can then be tested with various drugs to see which treatment is most effective for that particular person (personalised medicine in it’s purest form).

Some of the option available to Parkinson’s disease. Source: Nature

Imagination is literally the only limiting factor with regards to the possible uses of IPS cell technology.

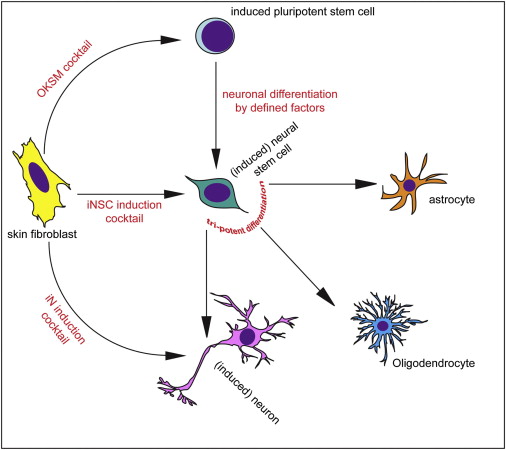

Shortly after Yamanaka’s research was published in 2006, however, the question was asked ‘rather than going back to a primitive state, can we simply change the fate of a mature cell directly?’ For example, turn a skin cell into a neuron.

This question was raised mainly to address the issue of ‘age’ in the modelling disease using IPS cells. Researchers questioned whether an aged mature cell reprogrammed into an immature IPS cell still carried the characteristics of an aged cell (and can be used to model diseases of the aged), or would we have to wait for the new cell to age before we can run experiments on it. Skin biopsies taken from aged people with neurodegenerative conditions may lose the ‘age’ element of the cell and thus an important part of the personalised medicine concept would be lost.

So researchers began trying to ‘re-program’ mature cells. Taking a skin cell and turning it directly into a heart cell or a brain cell.

And this is probably the craziest part of this whole post because they actually did it!

Different methods of inducing skin cells to become something else. Source: Neuron

In 2010, scientists from Stanford University published this report:

Title: Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors

Authors: Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M.

Journal: Nature. 2010 Feb 25;463(7284):1035-41.

PMID: 20107439

In this study, the researchers demonstrated that the activation of three genes (Ascl1, Brn2 and Myt1l) was sufficient to rapidly and efficiently convert skin cells into functional neurons in cell culture. They called them ‘iN’ cells’ or induced neuron cells. The ‘re-programmed’ skin cells made neurons that produced many neuron-specific proteins, generated action potentials (the electrical signal that transmits a signal across a neuron), and formed functional connection (or synapses) with neighbouring cells. It was a pretty impressive achievement, which they beat one year later by converting mature liver cells into neurons – Click here to read more on this – Wow!

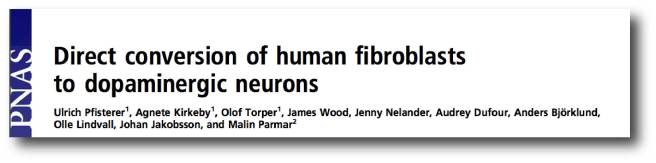

The next step – with regards to our Parkinson’s-related interests – was to convert skin cells directly into dopamine neurons (the cells most severely affected in the condition).

And guess what:

Title: Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to dopaminergic neurons.

Authors: Pfisterer U, Kirkeby A, Torper O, Wood J, Nelander J, Dufour A, Björklund A, Lindvall O, Jakobsson J, Parmar M

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108:10343-10348.

PMID: 21646515 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, Swedish researchers confirmed that activation of Ascl1, Brn2, and Myt1l re-programmed human skin cells directly into functional neurons. But then if they added the activation of two additional genes, Lmx1a andFoxA2 (which are both involved in dopamine neuron generation), they could convert skin cells directly into dopamine neurons. And those dopamine neurons displayed all of the correct features of normal dopamine neurons.

With the publication of this research, it suddenly seemed like anything was possible and people began make all kinds of cell types out of skin cells. For a good review on making neurons out of skin cells – Click here.

Given that all of this was possible in a cell culture dish, some researchers started wondering if direct reprogramming was possible in the body. So they tried.

And again, guess what:

Title: In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells.

Authors: Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA.

Journal: Nature. 2008 Oct 2;455(7213):627-32.

PMID: 18754011

Using the activation of three genes (Ngn3, Pdx1 and Mafa), the investigators behind this study re-programmed differentiated pancreatic exocrine cells in adult mice into cells that closely resemble b-cells. And all of this occurred inside the animals, while the animals were wandering around & doing their thing!

Now naturally, researchers in the Parkinson’s disease community began wondering if this could also be achieved in the brain, with dopamine neurons being produced from re-programmed cells.

And (yet again) guess what:

Title: Generation of induced neurons via direct conversion in vivo

Authors: Torper O, Pfisterer U, Wolf DA, Pereira M, Lau S, Jakobsson J, Björklund A, Grealish S, Parmar M.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 23;110(17):7038-43.

PMID: 23530235 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the Swedish scientists (behind the previous direct re-programming of skin cells into dopamine neurons) wanted to determine if they could re-program cells inside the brain. Firstly, they engineered skin cells with the three genes (Ascl1, Brn2a, & Myt1l) under the control of a special chemical – only in the presence of the chemical, the genes would be activated. They next transplanted these skin cells into the brains of mice and began adding the chemical to the drinking water of the mice. At 1 & 3 months after transplantation, the investigators found re-programmed cells inside the brains of the mice.

Next, the researchers improved on their recipe for producing dopamine neurons by adding the activation of two further genes: Otx2 and Lmx1b (also important in the development of dopamine neurons). So they were now activating a lot of genes: Ascl1, Brn2a, Myt1l, Lmx1a, FoxA2, Otx2 and Lmx1b. Unfortunately, when these reprogrammed cells were transplanted into the brain, few of them survived to become mature dopamine neurons.

The investigators then ask themselves ‘do we really need to transplant cells? Can’t we just reprogram cells inside the brain?’ And this is exactly what they did! They injected the viruses that allow for reprogramming directly into the brains of mice. The experiment was designed so that the cargo of the viruses would only become active in the astrocyte cells, not neurons. And when the researchers looked in the brains of these mice 6 weeks later, they found numerous re-programmed neurons, indicating that direct reprogramming is possible in the intact brain.

So what was so special about the research published last week about? Why the media hype?

The research published last week, by another Swedish group, took this whole process one step further: Not only did they re-program astrocytes in the brain to become dopamine neurons, but they also did this on a large enough scale to correct the motor issues in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Induction of functional dopamine neurons from human astrocytes in vitro and mouse astrocytes in a Parkinson’s disease model

Authors: di Val Cervo PR, Romanov RA, Spigolon G, Masini D, Martín-Montañez E, Toledo EM, La Manno G, Feyder M, Pifl C, Ng YH, Sánchez SP, Linnarsson S, Wernig M, Harkany T, Fisone G, Arenas E.

Journal: Nature Biotechnology (2017) doi:10.1038/nbt.3835

PMID: 28398344

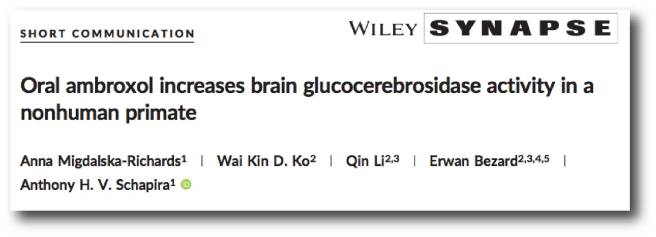

These researchers began this project 6 years ago with a new cocktail of genes for reprogramming cells to become dopamine neurons. They used the activation of NEUROD1, ASCL1 and LMX1A, and a microRNA miR218 (microRNAs are genes that produce RNA, but not protein – click here for more on this). These genes improved the reprogramming efficiency of human astrocytes to 16% (that is the percentage of astrocytes that were infected with the viruses and went on to became dopamine neurons). The researchers then added some chemicals to the reprogramming process that helps dopamine neurons to develop in normal conditions, and they observed an increase in the level of reprogramming to approx. 30%. And these reprogrammed cells display many of the correct properties of dopamine neurons.

Next the investigators decided to try this conversion inside the brains of mice that had Parkinson’s disease modelled in them (using a neurotoxin). The delivery of the viruses into the brains of these mice resulted in reprogrammed dopamine neurons beginning to appear, and 13 weeks after the viruses were delivered, the researchers observed improvements in the Parkinson’s disease related motor symptoms of the mice. The scientists concluded that with further optimisation, this reprogramming approach may enable clinical therapies for Parkinson’s disease, by the delivery of genes rather than transplanted cells.

How does this reprogramming work?

As we have indicated above, the re-programming utilises re-engineered viruses. They have been emptied of their disease causing elements, allowing us to use them as very efficient biological delivery systems. Importantly, retroviruses infect dividing cells and integrate their ‘cargo’ into the host cell’s DNA.

Retroviral infection and intergration into DNA. Source: Evolution-Biology

The ‘cargo’ in the case of IPS cells, is a copy of the genes that allow reprogramming (such as the Yamanaka genes), which the cell will then start to activate, resulting in the production of protein for those genes. These proteins subsequently go on to activate a variety of genes required for the maintenance of embryonic stem cells (and re-programming of mature cells).

And viruses were also used for the re-programming work in the brain as well.

There is the possibility that one day we will be able to do this without viruses – in 2013, researchers made IPS cells using a specific combination of chemicals (Click here to read more about this) – but at the moment, viruses are the most efficient biological targeting tool we have.

So what does it all mean?

Last week researchers is Sweden published research explaining how they reprogrammed some of the helper cells in the brains of Parkinsonian mice so that they turned into dopamine neurons and helped to alleviate the symptoms the mice were feeling.

This result and the trail of additional results outlined above may one day be looked back upon as the starting point for a whole new way of treating disease and injury to particular organs in the body. Suddenly we have the possibility of re-programming cells in our body to under take a new functions to help combat many of the conditions we suffer.

It is important to appreciate, however, that the application of this technology is still a long way from entering the clinic (a great deal of optimisation is required). But the fact that it is possible and that we can do it, raises hope of more powerful medical therapies for future generations.

As the researchers themselves admit, this technology is still a long way from the clinic. Improving the efficiency of the technique (both the infection of the cells and the reprogramming) will be required as we move down this new road. In addition, we will need to evaluate the long-term consequences of removing support cells (astrocytes) from the carefully balanced system that is the brain. Future innovations, however, may allow us to re-program stronger, more disease-resistant dopamine neurons which could correct the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease without being affected by the disease itself (as may be the case in transplanted cells – click here to read more about this).

Watch for a lot more research coming from this topic.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Greg Dunn (we love his work!)

For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the

For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the