In her best selling book, ‘Gut’, author Giulia Enders wrote the following:

‘Although doctors had known since the 1960s that patients with Parkinson’s disease have an increased incidence of stomach problems they did not know the nature of the connection between sore stomachs and trembling hands. It took a study of different population groups on the Pacific island of Guam to throw light on the subject. In some parts of the island, there was an astonishingly high incidence of Parkinson-like symptoms among the population. Those affected suffered from trembling hands, facial paralysis and motor problems. Researchers realised that the symptoms were most common in areas where people’s diets included cycad seeds. These seeds contain neurotoxins – substances that damage the nerves. Helicobacter pylori can produce an almost identical substance. When laboratory mice were fed with an extract of the bacteria without being infected with the living bacterium itself, the displayed very similar symptoms to the cycad eating Guamanians.’

While finding her book a very interesting read, we here at the Science of Parkinson’s were a little worried as to how the general audience would interpret this passage (“So Helico… whatever causes Parkinson’s disease?!?”).

But then this week a new study was published regarding Helicobacter pylori and Parkinson’s disease. And so we thought we’d do a post on it.

In 1982, two Australian scientists – Robin Warren and Barry Marshall – made an interesting discovery.

Barry Marshall (left) and Robin Warren. Source: AustraliaUnlimited

They were studying the association between bacterial infection and peptic ulcers. Their research was ridiculed by the establishment who did not believe that bacteria could even live in the harsh acidic environment of the gut let alone influence or affect it. The general consensus was that stomach ulcers were caused by stress, fatigue, and too much acid.

After some unsuccessful initial experiments, Marshall took the rather bold step of making himself a guinea pig in his own study: he drank a petri dish containing cultured Helicobacter pylori.

A petri dish of Helicobacter pylori. Yummy! Source: Liofilchem

Yes, I know how crazy that sounds, but that is what happened. And the resulting events changed the way we look at the intestinal system forever.

Marshall had expected the bacteria to take months (if not years) to embed and start to grow, so it came as a bit of a surprise when several days later he began feeling nausea and his mother commented about his bad breath. After a week, Marshall had a biopsy, which demonstrated severe inflammation and the growing of Helicobacter pylori bacteria in his gut. Warren and Marshall were awarded the Nobel prize in Medicine in 2005 for this work.

Since their discovery, we have discovered a small universe of microbes living in our intestinal system (and most of it is still waiting to be discovered). Importantly – as Miss Elders’ book emphasises – we are learning more and more about how the biological system living in our gut is influencing our bodies, both our normal and abnormal states of being.

There are even theories of Parkinson’s disease arising from our growing knowledge of the ‘microbiota’ (what scientists called the eco-system in our guts) and how it could be playing a role in the disease. And many of those theories involve Helicobacter pylori.

What is Helicobacter pylori?

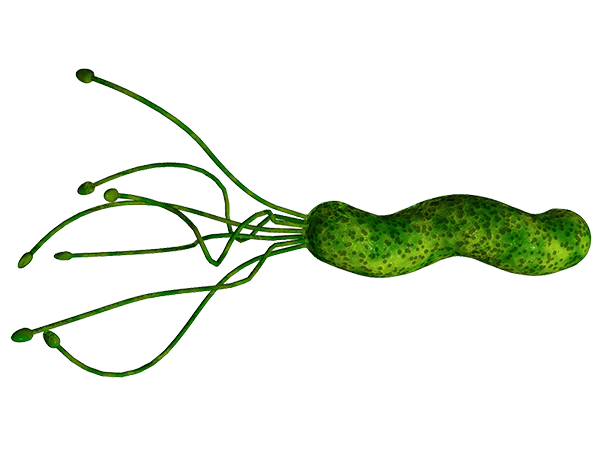

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral shaped bacterium that lives in the stomach and duodenum (that is the section of intestine just below stomach). Don’t be disturbed by that, the population of all microbes outnumber the cells in our body by approximately 10 to 1, and without them we wouldn’t last very long. And Helicobacter pylori are present in the gut of at least 50% of us (though 85% of people never display the symptoms of an infection).

Helicobacter pylori. Source: Helico

So are Helicobacter pylori involved in Parkinson’s disease?

There have been numerous studies that have assessed the Helicobacter pylori populations in the guts of people with Parkinson’s disease (for a very good open access review on this, please click here). These studies are difficult to judge, however, as the rate of Helicobacter pylori is very high and varies somewhat around the world. Different strains of Helicobacter pylori may be having different effects, but this is yet to be determined.

Helicobacter pylori does appear to have an effect, however, with regards to the standard treatment of Parkinson’s disease: L-dopa.

In 2001, Italian researchers noticed fluctuations in the absorption of L-dopa in six Helicobacter pylori infected people with Parkinson’s disease, but not in Helicobacter pylori-negative people with Parkinson’s disease. This was interesting, but even more interesting was that the ratings of these subjects (their UPDRS scores) decreased when they were treated with medication to eradicate Helicobacter pylori.

Title: Reduced L-dopa absorption and increased clinical fluctuations in Helicobacter pylori-infected Parkinson’s disease patients.

Authors: Pierantozzi M, Pietroiusti A, Sancesario G, Lunardi G, Fedele E, Giacomini P, Frasca S, Galante A, Marciani MG, Stanzione P.

Journal: Neurol Sci. 2001 Feb;22(1):89-91.

PMID: 11487216

Other studies have reported similar observations, including this study:

Title: Helicobacter pylori infection and motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Lee WY, Yoon WT, Shin HY, Jeon SH, Rhee PL.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2008 Sep 15;23(12):1696-700.

PMID: 18649391

The researchers in this study found that the onset time of L-dopa was longer, and the duration of the effect was shorter in people with Parkinson’s disease who also have an Helicobacter pylori infection (compared to people with Parkinson’s disease who are Helicobacter pylori negative). This data supports the idea that Helicobacter pylori may be disrupting the absorption of L-dopa. And again, after administering antibiotic treatment to people with Parkinson’s disease to eradicate Helicobacter pylori, the ‘onset’ time decreased and the duration of the L-dopa effect increased when compared to the pretreatment measures.

So there appears to be some indication that Helicobacter pylori may be affecting the situation in Parkinson’s disease.

But is there any evidence that Helicobacter pylori causes Parkinson’s disease?

To our knowledge, there has been one study that has suggested any kind of causative role for Helicobacter pylori in Parkinson’s disease. That study was presented at the Annual general meeting of the American Society for Microbiology at New Orleans in 2011:

Title: Helicobacter pylori Infection Induces Parkinson’s Disease Symptoms in Aged Mice.

Authors: Block: M. F. Salvatore, S. L. Spann, D. J. Mcgee, O. A. Senkovich, T. L. Testerman;

University: Louisiana State Univ. Hlth.Sci. Ctr.- Shreveport, Shreveport, LA.

Poster Presentation Number: 136

Poster Abstract:

Background: H. pylori has long been known to cause gastritis and ulcers, but mounting evidence suggests that this organism contributes to several extragastric diseases, including idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. It has been hypothesized that cholesteryl glucosides produced by H. pylori are the cause of neurotoxicity; however chronic inflammation may also cause neurological damage. We have recently developed a mouse model of H. pylori-mediated Parkinson’s disease which approximates many features of human disease, including locomotor dysfunction, decreased dopamine in certain brain regions, and increased susceptibility of older animals to Parkinsonian symptoms. Our experiments also revealed that a mutant strain causes more severe disease than the isogenic wild-type strain. AlpA and AlpB have previously been identified as adhesins.

Methods: We measured five locomotor activity parameters in aged mice persistently colonized with H. pylori SS1 AlpAB and in mice fed whole, killed H. pylori. Following euthanasia, we measured dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase content in the substantia nigra and dorsal striatum. We also measured effects of the AlpAB mutation on H. pylori adherence and pathogenesis.

Results: Long-term administration of food containing killed H. pylori causes locomotor deficits similar to those seen in H. pylori-infected animals. We found that AlpA and AlpB bind host laminin. Contrary to expectations, the AlpAB mutant causes severe inflammation in gerbils.

Conclusions: The finding that feeding killed H. pylori causes locomotor deficits similar to those seen with active infection supports the hypothesis that products produced by H. pylori are neurotoxic. Our results also suggest alterations in laminin binding by the AlpAB strain could impact interactions with the host. This new mouse model offers an unprecedented opportunity to examine the mechanisms through which H. pylori contributes to Parkinson’s disease in humans.

(Click here for the original abstract)

Unfortunately this research has not been formally published (in a peer-reviewed fashion or otherwise), so many of the details regarding the study are unknown to us. The implications, however, are very interesting and exciting. It would be a worthwhile endeavour for the study to be independently replicated.

But there was a study published last week that raised some interesting possibilities regarding a role for Helicobacter pylori in the onset of Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Augmentation of Autoantibodies by Helicobacter pylori in Parkinson’s Disease Patients May Be Linked to Greater Severity.

Authors: Suwarnalata G, Tan AH, Isa H, Gudimella R, Anwar A, Loke MF, Mahadeva S, Lim SY, Vadivelu J.

Journal: PLoS One. 2016 Apr 21;11(4):e0153725.

PMID: 27100827 (this research article is OPEN ACCESS if you want to read it)

The researchers in this study took blood from 30 Helicobacter pylori-positive people with Parkinson’s disease and 30 age- and gender-matched Helicobacter pylori-negative people with Parkinson’s disease. They then analysed the blood for autoantibodies (we’ve discussed these before in a previous post). Interestingly, some of the autoantibodies that were found to be elevated in Helicobacter pylori-positive group included antibodies that recognize proteins essential for normal brain function (such as Nuclear factor I subtype A (NFIA), Platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB) and Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A3 (eIFA3)). This suggests that Helicobacter pylori may be causing the immune system to attack proteins that are required, thus making people with Parkinson’s more vulnerable.

Finally, back to Miss Elder’s passage in her book ‘Gut’:

In the passage at the start of this post, we would suggest that Miss Elders may have been referring to ‘Lytico-bodig’ (also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia complex (ALS-PDC) – coined by Hirano and colleagues in 1961). ALS-PDC is a neurodegenerative disease of unknown causes that exists in the United States territory of Guam. In fact, during 1950s, it was one of the leading causes of death for the Chamorros people of of Guam.

As the name suggests the disease has elements of several neurodegenerative conditions, and it is considered a separate condition to Parkinson’s disease. There is no treatment for ALS-PDC. The Parkinsonian drug L-DOPA alleviates only some of the symptoms of ALS-PDC, and window of efficacy is a lot shorter (only 1-2 hours) than that of Parkinson’s disease. ALS-PDC occurs within families, but no genetic connection has been found yet, so most scientists believe it is predominantly environment-based.

β-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), is a neurotoxin produced by a bacteria called cyanobacteria and it has long been considered the culprit behind ALS-PDC. Miss Elders is correct that cycad seeds contain high levels of BMAA, and so too do animals that like eating the fleshy covering of the cycad seeds, such as flying foxes. Flying foxes were a popular dinner in Guam, but little did those consuming the meat realise that their meal probably contained high levels of BMAA. One theory of ALS-PDC causation is basically ‘Eat enough of those dinners across a lifetime and…’. But this theory is not supported by the evidence – flying foxes have been hunted to near extinction in Guam, but the rates of ALS-PDC have disappeared in parallel.

It is also interesting to note that high concentrations of BMAA are present in shark fins. Ignore any comments about the ‘libido enhancing properties’ and avoid shark fin soup.

While we here are very excited by the largely unexplored depths the gastrointestinal system and of the role that it could be playing in Parkinson’s disease, we think that Miss (soon to be Dr) Giulia Enders’ suggestion that Helicobacter pylori and Parkinson’s disease are intimately connected is a bit flimsy. Certainly unproven.

It is dangerous to write definitely about medically related research as it will often result in some individuals going off and self-testing all manner of different treatments in a desperate attempt to ‘cure themselves’.Sometimes this ‘definitive style’ is the suggestion of the editorial staff, hoping to cause something sensational and sell more books.

We are of the mind that more research is required in order to determine the role of bacteria (not just Helicobacter pylori) in Parkinson’s disease.

Having said all this, we still think that soon-to-be-Dr Enders’ book is a good read!

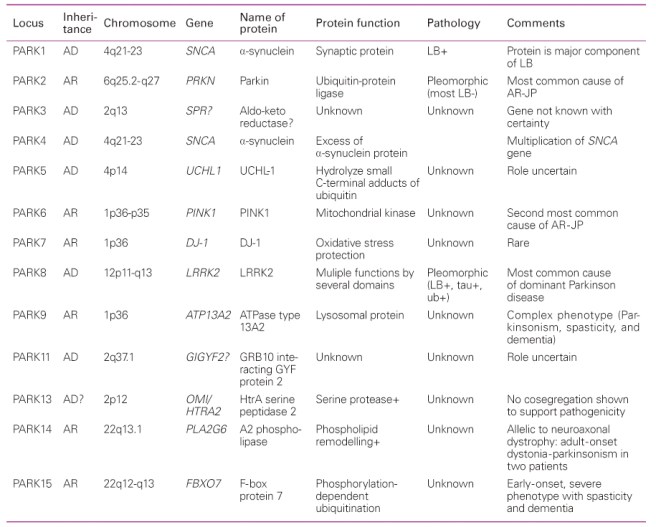

A schematic demonstrating the arrangement of DNA- Genes-Chromosomes. Source:

A schematic demonstrating the arrangement of DNA- Genes-Chromosomes. Source: