In 1991, Leu-Fen Lin and Frank Collins – both research scientists at a small biotech company in Boulder, Colorado – isolated a protein that was going to have an enormous impact on experimental therapeutic approaches for Parkinson’s disease over the next two decades. The company was called Synergen, and the protein they discovered was glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, or GDNF.

The structure of GDNF. Source: Wikipedia

A great deal has been written about GDNF and Parkinson’s disease (there are some very good books on the story of the development of GDNF as a drug), here we will provide an overview and look at what is currently happening.

So what is GDNF?

Glial cells are the support cells in the brain. From the Greek γλία and γλοία meaning “glue”, glial cells make up more than 50% percentage of the total number of cells in the brain – though this ratio can vary across different regions.

Large neurons supported by smaller glial cells. Source: Scientific Brains

Glials cells look after the ‘work horses’ – the neurons – by maintaining the environment surrounding the neurons and supplying them with supportive chemicals, called neurotrophic factors (neurotrophic = Greek: neuron – nerve; trophikós – pertaining to food/to feed). There are many types of neurotrophic factors, some having more beneficial effects on certain types of neurons and not other. GDNF is one of these neurotrophic factors. It was isolated from a cell culture of rat glial cells (hence the name: glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor), and what became clear very quickly after it’s discovery was that it dramatically revived dying dopamine neurons (the cells classically affected in Parkinson’s disease). Leu-Fen Lin and Frank Collins’s initial results were astounding and they were published in 1993. Many studies in animal models of Parkinson’s disease followed and in almost all of those studies the results were amazing (here is a good review of the early literature).

GDNF is a member of a larger family of neurotrophic factors and three other members of that family (called neurturin, persephin, and artemin – sounds like the Three Musketeers!) have also demonstrated positive effects on dying dopamine neurons. The positive/neuroprotective effect works via a series of receptors on the surface of cells. There a receptors that are specific for each of the GDNF family members discussed above:

The GDNF family. Source: Nature

And they each exert their positive affect in combination with a protein called ret proto-oncogene (RET). RET is a receptor tyrosine kinase, which is a cell-surface molecule that initiates signals inside the cell resulting in cell growth and survival. Dopamine neurons have most of these receptors and a lot of RET.

What has happened with GDNF in the clinic?

Given the results of the initial studies with GDNF (and its family members), clinical studies/trials were set up to test if similar effects would be seen in humans.

The very first clinical trial pumped GDNF into the fluid surrounding the brain, but the drug did not penetrate very deep into the brain and had limited effect. One side effect of the treatment was a hyper-sensitivity to pain (called hyperalgesia) – patients literally couldn’t tolerate the clothes touching their bodies.

This initial failure gave rise to another clinical study at the Frenchay Hospital in Bristol (UK) in which GDNF was released inside the brain, in an area called the striatum. Tiny plastic tubes were implanted in the brain allowing for the GDNF to be pumped in.

GDNF was pumped into the striatum (green area). Source: Bankiewicz lab

Although the number of subjects in the study was very small (only 5 people with Parkinson’s), the results of that particular study were simply amazing.

Title: Direct brain infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson disease.

Authors: Gill SS, Patel NK, Hotton GR, O’Sullivan K, McCarter R, Bunnage M, Brooks DJ, Svendsen CN, Heywood P.

Journal: Nat Med. 2003 May;9(5):589-95.

PMID: 12669033

The researchers reported that after just one year of GDNF treatment, there was:

- a 39% improvement in the off-medication motor ability (according to the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS))

- a 61% improvement in how subjects perceived their ability to go about daily activities.

- a 64% reduction in medication-induced dyskinesias (and they were not observed off medication)

- no serious clinical side effects

Importantly, the researchers conducted brain imaging studies on the subjects and a 28% increase in striatum dopamine storage after 18 months.

And that study was followed up by an outcome report two years later, which had similar results.

Title: Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in PD: a two-year outcome study.

Authors: Patel NK, Bunnage M, Plaha P, Svendsen CN, Heywood P, Gill SS.

Journal: Ann Neurol. 2005 Feb;57(2):298-302.

PMID: 15668979

And then the researchers published a case study of one patient, suggesting that the positive effects of GDNF were still having an impact 3 years after the drug had stopped being delivered:

Title: Benefits of putaminal GDNF infusion in Parkinson disease are maintained after GDNF cessation.

Authors: Patel NK, Pavese N, Javed S, Hotton GR, Brooks DJ, Gill SS.

Journal: Neurology. 2013 Sep 24;81(13):1176-8.

PMID: 23946313

There were two issues with this initial GDNF pump study however:

- The trial was open label. Both the subjects taking part and the physicians running the study knew who was getting the drug. The study was not blind.

- A larger double blind study did not find the same results.

The Amgen “Double-Blind” Trial

In 2003, based on the Bristol study results, the pharmaceutical company Amgen (which owned GDNF) initiated a double blind clinical trial for GDNF with 34 patients. Being double blind, both the researchers and the participants did not know who was getting GDNF or a control treatment. The procedure used to pump the GDNF into the brain was slightly different to that used in the Bristol study, and some have suggested that this may have contributed to the outcome of this study.

On 1st July 2004, Amgen announced that its clinical trial testing the efficacy of GDNF in treating advanced Parkinson’s had failed to demonstrate any clinical improvement after six months of use. Later that year (in September), Amgen halted the study completely citing two reasons:

- Pre-clinical data from non-human primates that had been treated in the highest dosage group for six months (followed by a three-month washout period) indicated a significant loss of neurons in an area of the brain called the cerebellum (which is involved in coordinating movement)

- They had detected “neutralizing antibodies” in two of the study participants.

The former was strange as it had never been detected in any other animal models previously reported, but the detection of antibodies was a more serious issue. Antibodies are made by cells to defend the body against foreign material. If the body begins to produce antibodies against GDNF, the immune system would clear the body of the GDNF drug, but also the body’s own natural supply of GDNF. The consequences of this are unknown, so Amgen decided to pull the plug on the trial.

What followed was a ugly chapter in the story of GDNF. Amgen refused to allow their study participants to continue to use GDNF when they requested it on compassion reasons. Lawyers then got involved (two lawsuits in 2005), but the judges decided in favour of Amgen.

There are many researchers around the world who still believe that GDNF represents an important treatment for Parkinson’s disease, and this has given rise to further clinical trials.

What is happening at the moment?

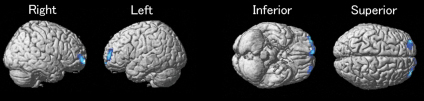

Currently there are several GDNF-based clinical trials being conducted. These trials have focused on three methods of delivery into the brain (specifically the striatum, which is the area of the brain where the most dopamine is released):

- Gene Therapy (GT)

- Encapsulated genetically modified cells (ECB)

- Pump delivery

A section of human brain demonstrating the different methods

for the delivery of GDNF to the striatum. Source: EPFL

The gene therapy (GT) trials have used genetically modified viruses to deliver the GDNF family members. One of the main GT trials involved a virus that was modified so that it produced large amounts of neurturin. Subjects were injected in the brain (specifically the striatum) and then the study participants were followed for 15 months. Unfortunately, this study failed to demonstrate any meaningful improvement in subjects with Parkinson’s disease.

The Encapsulated genetically modified cells (ECB) approach for the delivery of GDNF has been developed by company called NSgene and the trial currently on-going and we are waiting to hear the results of this study.

And finally, a new pump clinical trial for GDNF trial being run in Bristol (UK). The trial is being run by a company called MedGenesis (and funded by ParkinsonsUK and the CurePDTrust). The research team in Bristol have recruited 36 people with Parkinson’s disease to take part in their 9-month trial.

Dr Stephen Gill – Professor in Neurosurgery at University of Bristol – who conducting the current GDNF-pump study

This new trial should definitively tell us if there is a future for GDNF in Parkinson’s disease. The results of the study are expected at the end of 2016.

Reasons why GDNF may not work

While we do not want to dampen any optimism regarding GDNF, we believe that it is important to supply all points of view and as much information as possible. That said, in 2012, researchers in Sweden discovered that the GDNF neuroprotective effect is blocked in cells over-expressing alpha-synuclein – the protein that clumps together in Parkinson’s disease. In agreement with this, they found that RET was also reduced in dopamine neurons in people with Parkinson’s disease. Thus, it may be that people with Parkinson’s disease have a reduced ability to respond to GDNF.

Title: α-Synuclein-induced down-regulation of Nurr1 disrupts GDNF signaling in nigral dopamine neurons.

Authors: Decressac M, Kadkhodaei B, Mattsson B, Laguna A, Perlmann T, Björklund A.

Journal: Sci Transl Med. 2012 Dec 5;4(163):163ra156.

PMID: 23220632

Luckily, the Swedish researchers also found that another protein, called Nurr1, could rescue this reduction in GDNF response. And there is now a lot of research being conducted to investigate the positive effects of GDNF and Nurr1 in combination.

We will continue to follow this area and report any new findings as they come to hand.