We have previously written about the benefits of drinking coffee in reducing one’s chances of developing Parkinson’s disease (Click here for that post). Today, however, we shift our attention to another popular beverage: Tea.

Green tea in particular. Why? Because of a secret ingredient called Epigallocatechin Gallate (or EGCG).

Today’s post will discuss why EGCG may be of great importance to Parkinson’s disease.

Anyone fancy a cuppa? Source: Expertrain

INTERESTING FACT: after water, tea is the most widely consumed drink in the world.

In the United Kingdom only, over 165 million cups of tea were drunk per day in 2014 – that’s a staggering 62 billion cups per year. Globally 70 per cent of the world’s population (over the age of 10) drank a cup of tea yesterday.

Tea is derived from cured leaves of the Camellia sinensis, an evergreen shrub native to Asia.

The leaves of Camellia sinensis. Source: Wikipedia

There are two major varieties of Camellia sinensis: sinensis (which is used for Chinese teas) and assamica (used in Indian Assam teas). All versions of tea (White tea, yellow tea, green tea, etc) can be made from either variety, the difference is in the processing of the leaves.

The processing of different teas. Source: Wikipedia

There are at least six different types of tea based on the way the leaves are processed:

- White: wilted and unoxidized;

- Yellow: unwilted and unoxidized but allowed to yellow;

- Green: unwilted and unoxidized;

- Oolong: wilted, bruised, and partially oxidized;

- Black: wilted, sometimes crushed, and fully oxidized; (called “red tea” in Chinese culture);

- Post-fermented: green tea that has been allowed to ferment/compost (“black tea” in Chinese culture).

(Source: Wikipedia)

More than 75% of all tea produced in this world is considered black tea, 20% is green tea, and the rest is made up of white, Oolong and yellow tea.

What is the difference between Green tea and Black tea?

Green tea is made from Camellia sinensis leaves that are largely unwilted and heated through steaming (Japanese style) or pan-firing (Chinese style), which halts oxidation so the leaves retain their color and fresh flavor. Black tea leaves, on the other hand, are harvested, wilted and allowed to oxidize before being dried. The oxidation process causes the leaves to turn progressively darker.

So what does green tea have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

In 2006,this research paper was published:

Title: Small molecule inhibitors of alpha-synuclein filament assembly

Authors: Masuda M, Suzuki N, Taniguchi S, Oikawa T, Nonaka T, Iwatsubo T, Hisanaga S, Goedert M, Hasegawa M.

Journal: Biochemistry. 2006 May 16;45(19):6085-94.

PMID:16681381

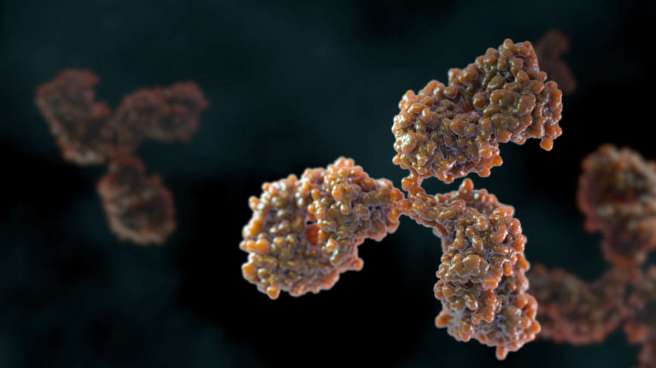

In this study, the researchers tested 79 different chemical compounds for their ability to inhibit the assembly of alpha-synuclein into fibrils. They found several compounds of interest, but one of them in particular stood out: Epigallocatechin Gallate or EGCG

The chemical structure of EGCG. Source: GooglePatents

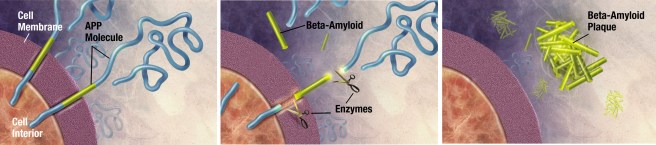

Now, before we delve into what exactly EGCG is, let’s take a step back and look at what is meant by the “assembly of alpha-synuclein into fibrils” (???).

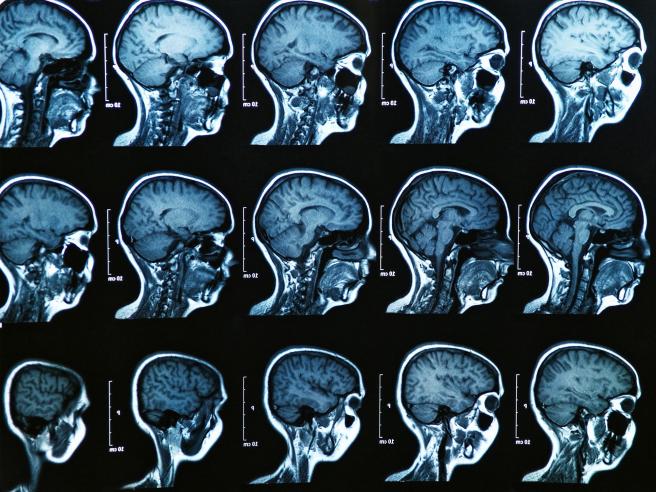

Alpha Synuclein

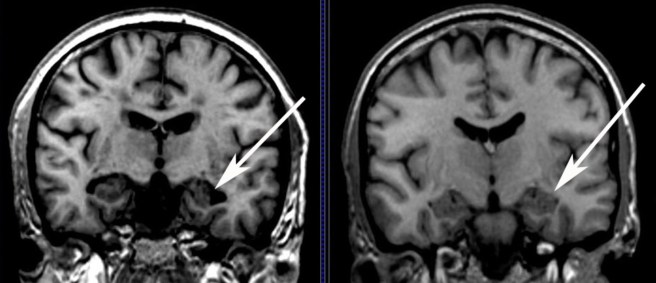

We have previously written a lot about alpha synuclein (click here for our primer page). It is a protein that has been closely associated with Parkinson’s disease for some time now. People with mutations in the alpha synuclein gene are more vulnerable to developing Parkinson’s disease, and the alpha synuclein protein is found in the dense circular clumps called Lewy bodies that are found in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease.

A lewy body (brown with a black arrow) inside a cell. Source: Cure Dementia

What role alpha synuclein plays in Parkinson’s disease and how it ends up in Lewy bodies is the subject of much research and debate. Many researchers, however, believe that it all depends on how alpha synuclein ‘folds’.

The misfolding of alpha synuclein

When a protein is produced (by stringing together amino acids in a specific order set out by RNA), it will then be folded into a functional shape that do a particular job.

Alpha synuclein is slightly different in this respect. It is normally referred as a ‘natively unfolded protein’, in that is does not have a defined structure. Alone, it will look like this:

Alpha synuclein. Source: Wikipedia

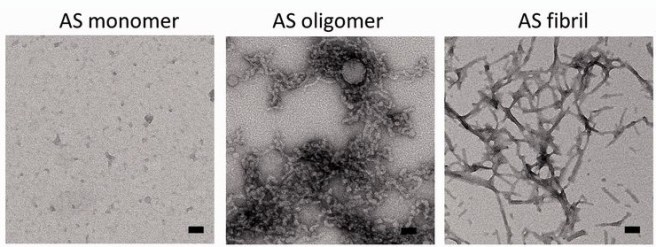

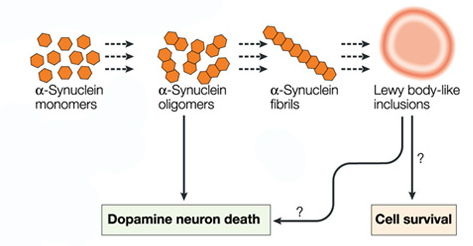

By itself, alpha synuclein is considered a monomer, or a single molecule that will bind to other molecules to form an oligomer (a collection of a certain number of monomers in a specific structure). In Parkinson’s disease, alpha-synuclein also aggregates to form what are called ‘fibrils’.

Microscopic images of Monomers, oligomers and fibrils. Source: Brain

Oligomer versions of alpha-synuclein are emerging as having a key role in Parkinson’s disease. They lead to the generation of fibrils and may cause damage by themselves.

Source: Nature

It is believed that the oligomer versions of alpha-synuclein is being passed between cells – and this is how the disease may be progressing – and forming Lewy bodies in each cells as the condition spreads.

For this reason, researchers have been looking for agents that can block the production of alpha synuclein fibrils and stabilize monomers of alpha synuclein.

And now we can return to EGCG.

What is EGCG?

Epigallocatechin Gallate is a powerful antioxidant. It has been associated with positive effects in the treatment of cancers (Click here for more on that).

And as the study mentioned near the top of this blog suggested, EGCG is also remarkably good at blocking the production of alpha synuclein fibrils and stabilizing monomers of alpha synuclein. If the alpha synuclein theory of Parkinson’s disease is correct, then EGCG could be the perfect treatment.

EGCG blocks the formation of oligomers. Source: Essays in Biochemistry

And there have been many studies replicating this effect:

Title: EGCG remodels mature alpha-synuclein and amyloid-beta fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity

Authors: Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Apr 27;107(17):7710-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107.

PMID: 20385841 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this particular study, the researchers found that EGCG has the ability to not only block the formation of of alpha synuclein fibrils and stabilize monomers of alpha synuclein, but it can also bind to alpha synuclein fibrils and restructure them into the safe form of aggregated monomers.

And again, what has Green tea got to do with Parkinson’s disease?

Green tea is FULL of EGCG.

In the production of Green tea, the picked leaves are not fermented, and as a result they do not go through the process of oxidation that black tea undergoes. This leaves green tea extremely rich in the EGCG, and black tea almost completely void of EGCG. Green tea is also superior to black tea in the quality and quantity of other antioxidants.

What clinical studies have been done on EGCG and Parkinson’s disease?

Two large studies have looked at whether tea drinking can lower the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Both studies found that black tea is associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease, but one of the studies found that drinking green tea had no effect (Click here and here for more on this). Now the positive effect of black tea is believed to be associated with the high level of caffeine, which is a confounding variable in these studies. Even Green tea has some caffeine in it – approximately half the levels of caffeine compared to black tea.

The levels of EGCG in these studies were not determined and we are yet to see a proper clinical trial of EGCG in Parkinson’s disease. EGCG has been clinically tested in humans (Click here for more on that), so it seems to be safe. And there is an uncompleted clinical trial of EGCG in Huntington’s disease (Click here for more) which we will be curious to see the results of.

So what does it all mean?

Number 1.

It means that if the alpha-synuclein theory of Parkinson’s disease is correct, then more research should be done on EGCG. Specifically a double-blind clinical trial looking at the efficacy of this antioxidant in slowing down the condition.

Number 2.

It means that I now drink a lot of green tea.

Usually mint flavoured (either Teapigs or Twinnings – please note: SoPD is not a paid sponsor of these products, though some free samples would be appreciated!).

It’s very nice. Have a try.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from WeightLossExperts