Imagine discovering a protein that could make the power supply of your cells healthier AND perhaps provide a new therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease.

That would be a pretty big deal right?

Well, this week, researchers may have found just such a protein. In today’s post we will review their finding and discuss what it means for Parkinson’s disease.

This is Dr Miguel Martins:

Source: Tox.mrc.ac.uk

He’s a dude.

Dr Martins is a group leader at the MRC toxicology unit in Leicester – a city in the East Midlands of England.

Leicester. Source: Keithvazmp

Leicester. Source: Keithvazmp

You may have heard of Leicester. Last year their football team had a dream season, miraculously winning the Premier league title despite starting with odds of 5000:1.

Last season’s winners. Source: Goal.com

This season, however,….well, uh…

Let’s move on, shall we.

Recently we reviewed Dr Martins research group’s work on ‘Pink flies’ and how they survive longer on Niacin rich diets (Click here for that post). He and his group were again publishing research this week, involving new a new study highlighting a protein that may help with keeping mitochondria healthy.

What are mitochondria?

Good question.

Mitochondria are the power house of each cell. They keep the lights on. Without them, the lights go out and the cell dies.

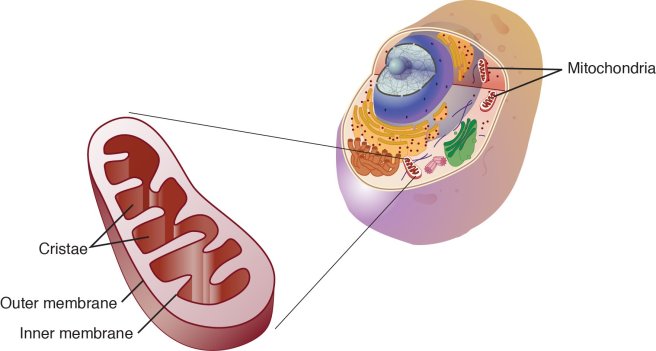

Mitochondria and their location in the cell. Source: NCBI

You may remember from high school biology class that mitochondria are bean-shaped objects within the cell. They convert energy from food into Adenosine Triphosphate (or ATP). ATP is the fuel which cells run on. Given their critical role in energy supply, mitochondria are plentiful and highly organised within the cell, being moved around to wherever they are needed.

So what has Dr Martins group found?

This week they published this study:

Title: dATF4 regulation of mitochondrial folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism is neuroprotective.

Authors: Celardo I, Lehmann S, Costa AC, Loh SH, Miguel Martins L.

Journal: Cell Death Differ. 2017 Feb 17. [Epub ahead of print]

PMID: 28211874 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In the study, the researchers were interested in determining what changes occur in the flies that are missing the Parkinson’s disease associated genes PINK1 or PARKIN, particularly which transcription factors are affected.

What is a transcription factor?

Another good question.

Ok, so you remember your high school science class when the adult at the front of the class was explaining biology 101? And they were saying that DNA gives rise to RNA, RNA gives rise to protein? The central dogma of biology. Remember this?

The basic of biology. Source: Youtube

Ultimately this DNA-RNA-Protein mechanism is a circular cycle, because the protein that is produced using RNA is required at all levels of this process. Some of the protein is required for making RNA from DNA, while other proteins are required for making protein from the RNA instructions.

A transcription factor is a protein that is involved in the process of converting (or transcribing) DNA into RNA.

Importantly, a transcription factor can be an ‘activator’ of transcription – that is initiating or helping the process of generating RNA from DNA.

An example of a transcriptional activator. Source: Khan Academy

Or it can be a repressor of transcription – blocking the machinery (required for generating RNA) from doing it’s work.

An example of a transcriptional repressor. Source: Khan Academy

In their study, Dr Martins and colleagues were looking for changes in the levels of proteins that either initiate or repress transcription, as these are the proteins that are ultimately at the start of the process of making things happen.

And what do Parkin and Pink1 actually do?

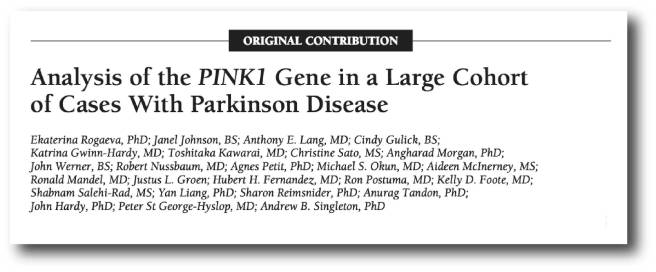

About 10% of cases of Parkinson’s disease can be attributed to genetic mutations in particular genes. PINK1 and PARKIN are two of those genes.

People with particular mutations in the PINK1 or PARKIN gene are vulnerable to developing an early onset form of Parkinson’s disease.

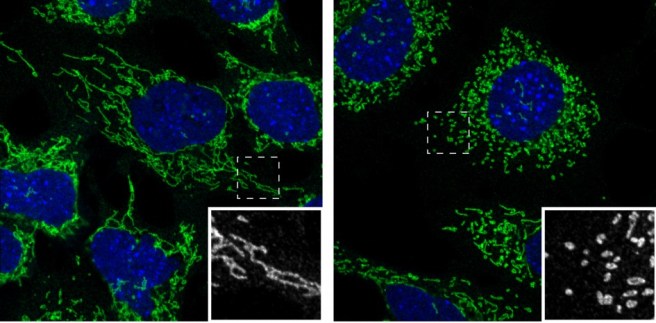

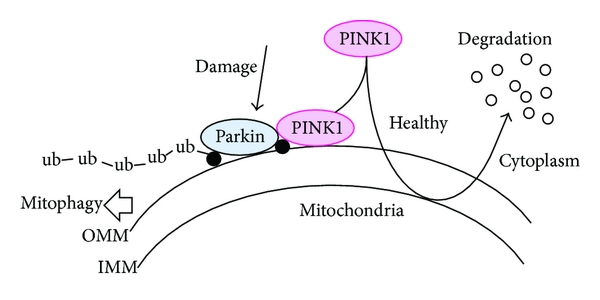

As to what the protein that is generated from PINK1 or PARKIN DNA & RNA, well in normal, healthy cells, the PINK1 protein is absorbed by mitochondria and eventually degraded. In unhealthy cells, however, this process is inhibited and PINK1 starts to accumulate on the outer surface of the mitochondria. There, it starts grabbing the PARKIN protein. This pairing is a signal to the cell that this particular mitochondria is not healthy and needs to be removed.

Pink1 and Parkin in normal (right) and unhealthy (left) situations. Source: Hindawi

The process by which mitochondria are removed is called autophagy. Autophagy is an absolutely essential function in a cell. Without it, old proteins will pile up making the cell sick and eventually it dies. Through the process of autophagy, the cell can break down the old protein, clearing the way for fresh new proteins to do their job.

Think of autophagy as the waste disposal process of the cell.

In the absence of PINK1 and PARKIN – as is the case in some people with Parkinson’s disease who have genetic mutations in these genes – we believe that sick/damaged mitochondria start to pile up and are not disposed of appropriately. This results in the cell dying.

Ok, so the researchers were looking for transcription factors that change in the absence of PINK1 and PARKIN. How did they do this experiment?

They used flies.

PINK flies. Source: Wallpapersinhq

The researchers took the heads (yes, I know, delightful stuff) of ‘young’ 3-day-old Pink1 and Parkin mutant flies and compared them to ‘aged’ heads from 21- and 30-day-old Parkin and Pink1 mutant flies, respectively. The comparison was specifically looking at transcription factors that change over time.

This analysis revealed a protein called activating transcription factor 4 (or ATF4).

The researchers found that ATF4 levels were higher in both Pink1 and Parkin mutants than levels in control flies. Importantly, the researchers next looked at the genes that this transcription factor (ATF4) was regulating, and they found that ATF4 was encouraging the production of proteins that protect mitochondria. The researchers noticed that when they reduced ATF4 in flies, the levels of these critical mitochondrial proteins dropped as well.

When the researchers reduced the levels of each of these critical mitochondrial proteins in flies, it resulted in impaired climbing ability (suggesting a locomotor deficit) and decreased lifespan. Interestingly, these protective mitochondrial proteins are increased in the Pink1 and Parkin flies, suggesting that efforts to keep the mitochondria healthy are active inside the cells.

Finally, the researchers increased the levels of these protective mitochondrial proteins in the Pink1 and Parkin mutants and they found that the mitochondrial function was improved, and neuronal cell loss was avoided. They concluded that their findings demonstrate a central role for ATF4 signalling in Parkinson’s disease and that this protein may represent a target for new therapeutic strategy.

So what does it all mean?

The researchers behind this study were looking for biological pathways that are altered in genetic forms of Parkinson’s disease and they have identified a protein that is involved with keeping mitochondria healthy. This pathway could represent a new therapeutic target for future treatments, and also opens a new door in our understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

ATF4 is currently not directly targeted by any medications (that we are aware of), but there are drugs in clinical trials that target proteins that subsequently activate ATF4. For example, Oncoceutics Inc. have a drug candidate called ONC201 (currently in phase II trials for brain cancer) which kills solid tumor cells by triggering an stress response which is dependent on ATF4 activation.

Source: Oncoceutics Inc

We are not for a second suggesting that this is a viable drug for Parkinson’s disease (so PLEASE DON’T rush out and besiege the company for all of their stocks!) – ATF4 should be considered a very experimental target until these results are replicated by independent research groups. We are mentioning ONC201 here simply to indicate that there is a field of research surrounding this potential target (ATF4) and it may be worthwhile for the Parkinson’s community to follow up this line of investigation.

We are assuming that while Leicester football club is struggling, the Martins lab are currently investigating compounds that activate ATF4 (and the other critical mitochondrial proteins), and we will report any follow up work as it comes to hand.

Watch this space.

And if nothing we’ve written here makes any sense, the good folks at Leicester University have kindly provided a short video explaining the research:

Postscript (March 2017):

The Martins lab have done it again!

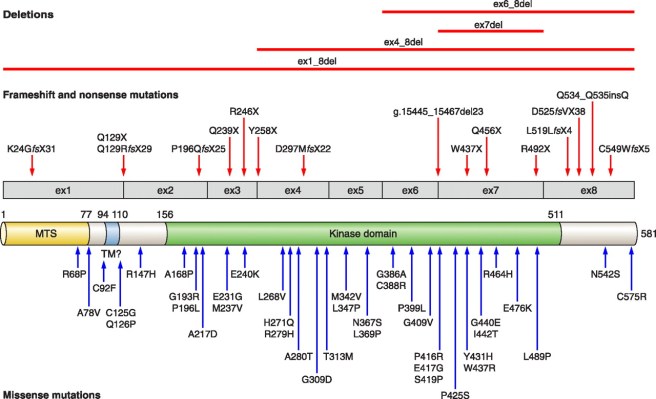

This time in the OPEN ACCESS online journal Science Matters, they have published this article:

Title: Folinic acid is neuroprotective in a fly model of Parkinson’s disease associated with pink1 mutations

Authors: Lehmann S , Jardine J, Garrido – Maraver J, Loh SH, & Martins LM

Journal: Science Matters

In this study, the researchers demonstrated that a folinic acid-enriched diet might delay or prevent the neuronal loss in people with PINK1 associated Parkinson’s disease. They present data suggesting that beginning an intake of Folinic acid in early to middle stages of adulthood prevents the degeneration of dopamine neurons in pink1 mutant flies.

Folinic acid (also known as leucovorin) is a medication used to decrease the toxic effects of chemotherapy drugs. The pharmacokinetics of leucovorin suggests that it readily crosses the blood-brain-barrier (Source), so it would be possible for a clinical trial to be set up in human. Before taking that path, however, more testing is required (ideally in a mammalian model of Parkinson’s disease).

Amazing that all these results are coming from silly old flies though, huh?

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Tox.mrc.ac.uk