We have been contacted by some readers asking about a new stem cell transplantation clinical trial for Parkinson’s disease about to start in China (see the Nature journal editorial regarding this new trial by clicking here).

While this is an exciting development, there have been some concerns raised in the research community regarding this trial.

In today’s post, we will discuss what is planned and what it will mean for stem cell transplantation research.

Brain surgery. Source Bionews-tx

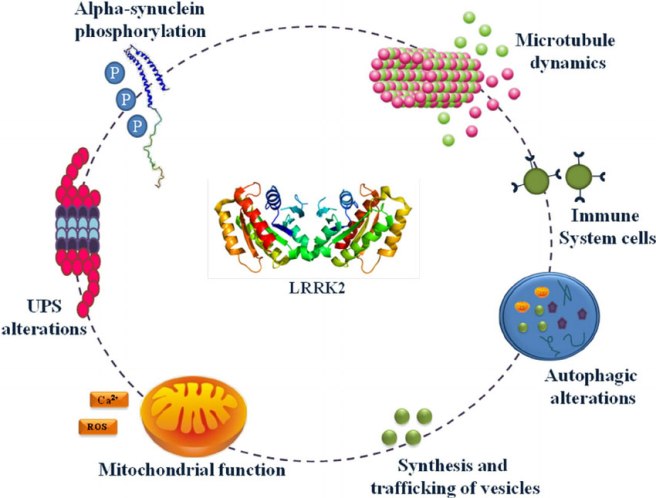

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition.

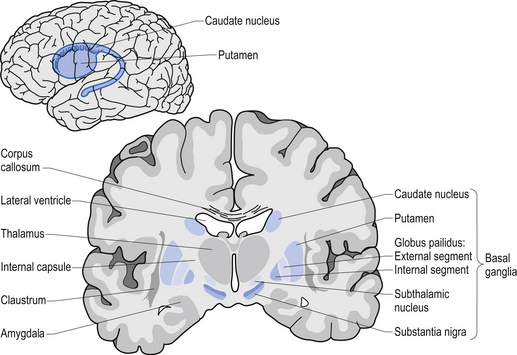

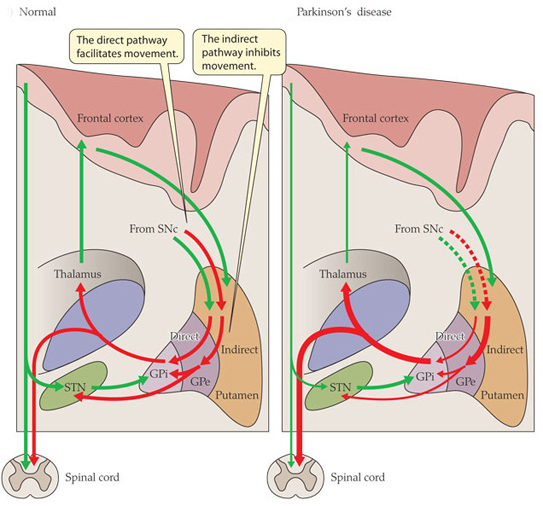

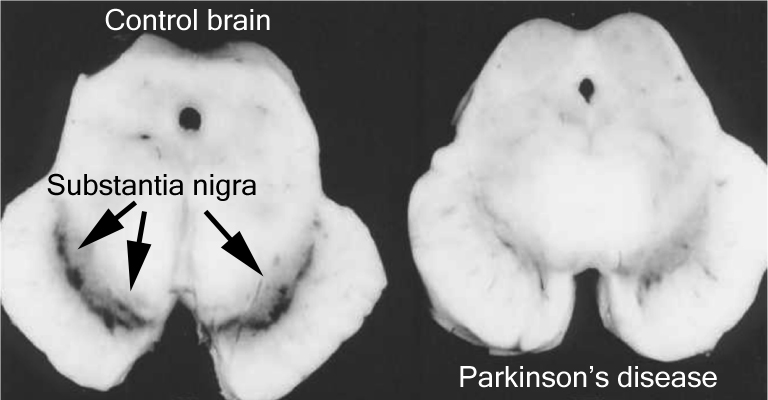

This means that cells in the brain are slowly being lost over time. What makes the condition particularly interesting is that certain types of brain cells are more affected than others. The classic example of this is the dopamine neurons in an area of the brain called the substantia nigra, which resides in the midbrain.

The number of dark pigmented dopamine cells in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source: Adapted from Memorangapp

Approximately 50% of the dopamine neurons in the midbrain have been lost by the time a person is diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (note the lack of dark colouration in the substantia nigra of the Parkinsonian brain in the image above), and as the condition progresses the motor features – associated with the loss of dopamine neurons – gradually get worse. This is why dopamine replacement treatments (like L-dopa) are used for controlling the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

A lot of research effort is being spent on finding disease slowing/halting treatments, but these will leave many people who have already been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease still dealing with the condition. What those individuals will require is a therapy that will be able to replace the lost cells (particularly the dopamine neurons). And researchers are also spending a great deal of time and effort on findings ways to do this. One of the most viable approaches at present is cell transplantation therapy. This approach involves actually injecting cells back into the brain to adopt the functions of the lost cells.

How does cell transplantation work?

We have discussed the history of cell transplantation in a previous post (Click here to read that post), and today we are simply going to focus on the ways this experimental treatment is being taken forward in the clinic.

Many different types of cells have been tested in cell transplantation experiments for Parkinson’s disease (Click here for a review of this topic), but to date the cells that have given the best results have been those dissected from the developing midbrain of aborted embryos.

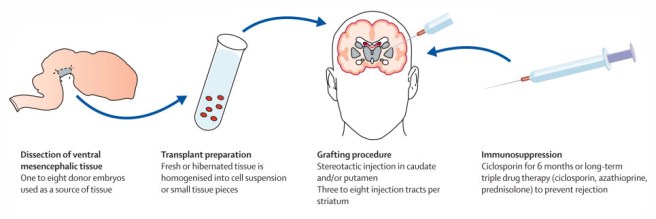

This now old fashioned approach to cell transplantation involved dissecting out the region of the developing dopamine neurons from a donor embryo, breaking up the tissue into small pieces that could be passed through a tiny syringe, and then injecting those cells into the brain of a person with Parkinson’s disease.

The old cell transplantation process for Parkinson’s disease. Source: The Lancet

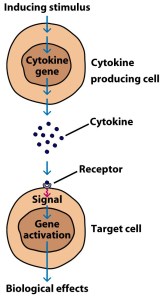

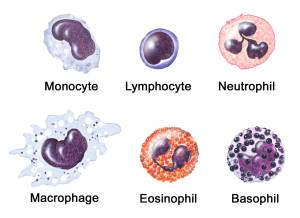

Critically, the people receiving this sort of transplant would require ‘immunosuppression treatment’ for long periods of time after the surgery. This additional treatment involves taking drugs that suppress the immune system’s ability to defend the body from foreign agents. This step is necessary, however, in order to stop the body’s immune system from attacking the transplanted cells (which would not be considered ‘self’ by the immune system), allowing those cells to have time to mature, integrate into the brain and produce dopamine.

The transplanted cells are injected into an area of the brain called the putamen. This is one of the main regions of the brain where the dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra release their dopamine. The image below demonstrates the loss of dopamine (the dark staining) over time as a result of Parkinson’s disease (PD):

The loss of dopamine in the putamen as Parkinson’s disease progresses. Source: Brain

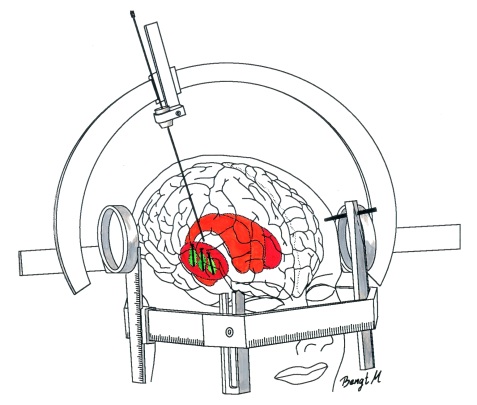

In cell transplant procedures for Parkinson’s disease, multiple injections are usually made in the putamen, allowing for deposits in different areas of the structure. These multiple sites allow for the transplanted cells to produce dopamine in the entire extent of the putamen. And ideally, the cells should remain localised to the putamen, so that they are not producing dopamine in areas of the brain where it is not desired (possibly leading to side effects).

Targeting transplants into the putamen. Source: Intechopen

Postmortem analysis – of the brains of individuals who have previously received transplants of dopamine neurons and then subsequently died from natural causes – has revealed that the transplanted cells can survive the surgical procedure and integrate into the host brain. In the image below, you can see rich brown areas of the putamen in panel A. These brown areas are the dopamine producing cells (stained in brown). A magnified image of individual dopamine producing neurons can be seen in panel B:

Transplanted dopamine neurons. Source: Sciencedirect

The transplanted cells take several years to develop into mature neurons after the transplantation surgery, and the benefits of the transplantation technique may not be apparent for some time (2-3 years on average). Once mature, however, it has also been demonstrated (using brain imaging techniques) that these transplanted cells can produce dopamine. As you can see in the images below, there is less dopamine being processed (indicated in red) in the putamen of the Parkinsonian brain on the left than the brain on the right (several years after bi-lateral – both sides of the brain – transplants):

Brain imaging of dopamine processing before and after transplantation. Source: NIH

Sounds like a great therapy for Parkinson’s disease right?

So why aren’t we doing it???

Two reasons:

1. The tissue used in the old approach for cell transplantation in Parkinson’s disease was dissected from embryonic brains. Obviously there are serious ethical and moral problems with using this kind of tissue. There is also a difficult problem of supply: tissue from at least 3 embryos is required for transplanting each side of the brain (6 embryos in total). Given these issues, researchers have focused their attention on a less controversial and more abundant supply of cells: brain cells derived from embryonic stem cells (the new approach to cell transplantation).

Human embryonic stem cells. Source: Wikipedia

2. The second reason why cell transplantation is not more widely available is that in the mid 1990’s, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided funding for the two placebo-controlled, double blind studies to be conducted to test the efficacy of the approach. Unfortunately, both studies failed to demonstrate any beneficial effects on Parkinson’s disease features.

In addition, many (15% – 50%) of transplanted subjects developed what are called ‘graft-induced dyskinesias’. This involves the subjects display uncontrollable/erratic movement (or dyskinesias) as a result of the transplanted cells. Interestingly, patients under 60 years of age did show signs of improvement on when assessed both clinically (using the UPDRS-III) and when assessed using brain imaging techniques (increased F-dopa uptake on PET).

Both of the NIH trials have been criticised by experts in the field for various procedural failings that could have contributed to the failures. But the overall negative results left a dark shadow over the technique for the better part of a decade. Researchers struggled to get funding for their research.

And this is the reason why many researchers are now urging caution with any new attempts at cell transplantation clinical trials in Parkinson’s disease – any further failures will really harm the field, if not kill if off completely.

Are there any clinical trials for cell transplantation in Parkinson’s disease currently being conducted?

Yes, there are currently two:

Firstly there is the Transeuro being conducted in Europe.

The Transeuro trial. Source: Transeuro

The Transeuro trial is an open label study, involving 40 subjects, transplanted in different sites across Europe. They will receive immunosuppression for at least 12 months post surgery, and the end point of the study will be 3 years post surgery, with success being based on brain imaging of dopamine release from the transplanted cells (PET scans). Based on the results of the previous NIH funding double blind clinical studies discussed above, only subject under 65 years of age have been enrolled in the study.

The European consortium behind the Transeuro trial. Source: Transeuro

In addition to testing the efficacy of the cell transplantation approach for Parkinson’s disease, another goal of the Transeuro trial is to optimise the surgical procedures with the aim of ultimately shifting over to an embryonic stem cells oriented technique in the near future with the proposed G-Force embryonic stem cell trials planned for 2018 (the Transeuro is testing the old approach to cell transplantation).

The second clinical study of cell transplantation for Parkinson’s disease is being conducted in Melbourne (Australia), by an American company called International Stem Cell Corporation.

This study is taking the new approach to cell transplantation, but the company is using a different type of stem cell to produce dopamine neurons in the Parkinsonian brain.

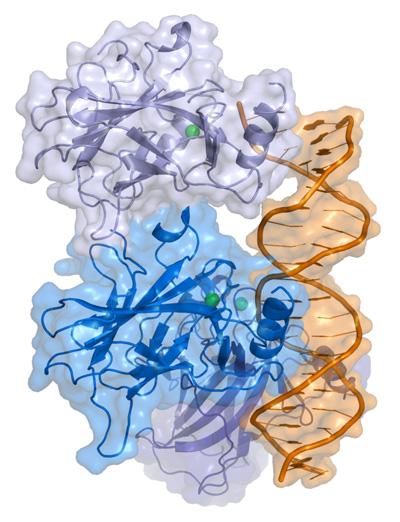

Specifically, the researchers will be transplanting human parthenogenetic stem cells-derived neural stem cells (hpNSC). These hpNSCs come from an unfertilized egg – that is to say, no sperm cell is involved. The female egg cell is chemically encouraged to start dividing and then it becoming a collection of cells that is called a blastocyst, which ultimately go on to contain embryonic stem cell-like cells.

The process of attaining embryonic stem cells. Source: Howstuffworks

This process is called ‘Parthenogenesis’, and it’s not actually as crazy as it sounds as it occurs naturally in some plants and animals (Click here to read more about this). Proponents of the parthenogenic approach suggest that this is a more ethical way of generating ES cells as it does not result in the destruction of a viable organism.

Regular readers of this blog will be aware that we are extremely concerned about this particular trial (Click here and here to read previous posts about this). Specifically, we worry that there is limited preclinical data from the company supporting the efficacy of these hpNSC cells being used in the clinical study (for example, researchers from the company report that the hpNSC cells they inject spread well beyond the region of interest in the company’s own published preclinical research – not an appropriate property for any cells being taken to the clinic). We have also expressed concerns regarding the researchers leading the study making completely inappropriate disclosures about the study while the study is ongoing (Click here to read more about this). Such comments only serve the interests of the company behind the study. And this last concern has been raised again with a quote in the Nature editorial about the Chinese trial:

“Russell Kern, chief scientific officer of the International Stem Cell Corporation in Carlsbad, California, which is providing the cells for and managing the Australian trial, says that in preclinical work, 97% of them became dopamine-releasing cells” (Source)

We are unaware of any preclinical data produced by Dr Kern and International Stem Cell Corporation…or ANY other research lab in the world that has achieved 97% dopamine-releasing cells. We (and others) would be interested in learning more about Dr Kerns amazing claim.

The International Stem Cell Corporation clinical trial is ongoing. For more details about this second ongoing clinical trial, please click here.

So what do we know about the new clinical study?

The clinical trial (Titled: A Phase I/II, Open-Label Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of Striatum Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells-derived Neural Precursor Cells in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease) will take place at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University in Henan province.

The researchers are planning to inject neuronal-precursor cells derived from embryonic stem cell into the brains of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. They have 10 subjects that they have found to be well matched to the cells that they will be injecting, which will help to limit the chance of the cells being rejected by the body.

- Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events, as assessed by brain imaging and blood examination at 6 months post transplant.

-

Number of subjects with adverse events (such as the evidence of transplant failure or rejection)

In addition to these, there will also be a series of secondary outcome measures, which will include:

- Change in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) score at 12 months post surgery, when compared to baseline scores. Each subject was independently rated by two observers at each study visit and a mean score was calculated for analysis.

- Change in DATscan brain imaging at 12 months when compared to a baseline brain scan taken before surgery. DATscan imaging provides an indication of dopamine processing.

- Change in Hoehn and Yahr Stage at 12 months, compared to baseline scores. The Hoehn and Yahr scale is a commonly used system for Parkinson’s disease.

The trial will be a single group, non-randomized analysis of the safety and efficacy of the cells. The estimated date of completion is December 2020.

Why are some researchers concerned about the study?

Professor Qi Zhou, a stem-cell specialist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Zoology will be leading the study and he has a REALLY impressive track record in the field of stem cell biology. His team undertaking this study have a great deal of experience working with embryonic stem cells, having published some extremely impressive research on this topic. But, (and it’s a big but) they have published a limited amount of research in peer-reviewed journals on cell transplantation in models of Parkinson’s disease. Lorenz Studer is one of the leading scientists in this field, was quoted in an editorial in the journal Nature this week:

“Lorenz Studer, a stem-cell biologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City who has spent years characterizing such neurons ahead of his own planned clinical trials, says that “support is not very strong” for the use of precursor cells. “I am somewhat surprised and concerned, as I have not seen any peer-reviewed preclinical data on this approach,” he says.” (Source)

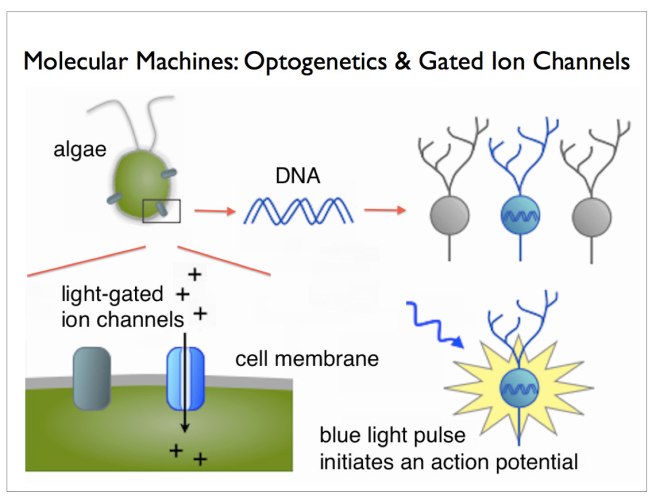

In addition to the lack of published research by the team undertaking the trial, the research community is also worried about the type of cells that are going to be transplanted in this clinical trial. Most of the research groups heading towards clinical trials in this area are all pushing embryonic stem cells towards a semi-differentiated state. That is, they are working on recipes that help the embryonic stem cells grow to the point that they have almost become dopamine neurons. Prof Zhou and his colleagues, however, are planning to transplant a much less differentiated type of cell called a neural-precursor cell in their transplants.

Neuronal-precursor cells. Source: Wired

Neuronal-precursors are very early stage brain cells. They are most likely being used in the study because they will survive the transplantation procedure better than a more mature neurons which would be more sensitive to the process – thus hopefully increasing the yield of surviving cells. But we are not sure how the investigators are planning to orient the cells towards becoming dopamine neurons at such an early stage of their development. Neuronal-precursors could basically become any kind of brain cell. How are the researchers committing them to become dopamine neurons?

Are these concerns justified?

We feel that there are justified reasons for concern.

While Prof Zhou and his colleagues have a great deal of experience with embryonic stem cells and have published very impressive research on that topic, the preclinical data for this trial is limited. In 2015, the research group published this report:

Title: Lmx1a enhances the effect of iNSCs in a PD model

Authors: Wu J, Sheng C, Liu Z, Jia W, Wang B, Li M, Fu L, Ren Z, An J, Sang L, Song G, Wu Y, Xu Y, Wang S, Chen Z, Zhou Q, Zhang YA.

Journal: Stem Cell Res. 2015 Jan;14(1):1-9.

PMID: 25460246 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers engineered embryonic stem cells to over-produce a protein called LMX1A to help produce dopamine neurons. LMX1A is required for the development of dopamine neurons (Click here to read more about this). The investigators then grew these cells in cell culture and compared their ability to develop into dopamine neurons against embryonic stem cells with normal levels of LMX1A. After 14 days in cell culture, 16% of the LMX1A cells were dopamine neurons, compared to only 5% of the control cells.

When the investigators transplanted these cells into a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease, they found that the behavioural recovery in the mice did not differ from the control injected mice, and when they looked at the brains of the mice 11 weeks after transplantation “very few engrafted cells had survived”.

In addition to this previously published work, the Chinese team do have unpublished research on 15 monkeys that have undergone the neuronal-precursor cell transplantation procedure having had Parkinson’s disease induced using a neurotoxin. The researchers have admitted that they initially did not see any improvements in movement (which is expected given the slow maturation of the cells). At the end of the first year, however, they examined the brains of some of the monkeys and they found that the transplanted stem cells had turned into dopamine-releasing cells (exactly what percentage of the cells were dopamine neurons is yet to be announced). The monkey study has been running for several years now and they have seen a 50% improvement in the motor ability of the remaining monkeys, supported by brain imaging data. The publication of this research is in preparation, but it probably won’t be available until after the trial has started.

So yes, there is a limited amount of preclinical research supporting the clinical trial.

As for concerns regarding the type of cells that are going to be transplanted:

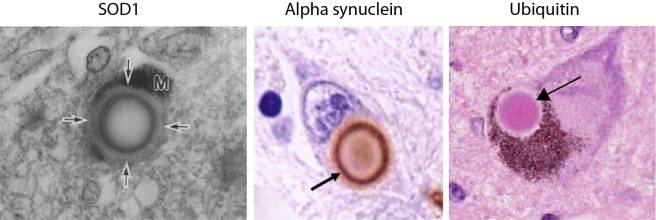

Embryonic stem cells have robust tumour forming potential. If you inject them into the brain of mice, there is the potential for them to develop into dopamine neurons, but also tumours:

Title: Embryonic stem cells develop into functional dopaminergic neurons after transplantation in a Parkinson rat model

Authors: Bjorklund LM, Sánchez-Pernaute R, Chung S, Andersson T, Chen IY, McNaught KS, Brownell AL, Jenkins BG, Wahlestedt C, Kim KS, Isacson O.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Feb 19;99(4):2344-9.

PMID: 11782534 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you want to read it)

In this study, the researchers found that of the twenty-five rats that received embryonic stem cell injections into their brains to correct the modelled Parkinson’s disease, five rats died before completed behavioural assessment and the investigators found teratoma-like tumours in their brains – less than 16 weeks after the cells had been transplanted.

A teratoma (white spot) inside a human brain. Source: Radiopaedia

Given this risk of tumour formation, research groups in the cell transplantation field have been trying to push the embryonic stem cells as far away from their original pluripotent state and as close to a dopamine fate as possible without producing mature dopamine neurons which will not survive the transplantation procedure very well.

Prof Zhou’s less mature neuronal-precursor cells are closer to embryonic stem cells than dopamine neurons on this spectrum than the kinds of cells other research groups are testing in cell transplantation experiments. As a result, we are curious to know what precautions the investigators are taking to limit the possibility of an undifferentiated, still pluripotent embryonic stem cell from slipping into this study (the consequences could be disastrous). And given their results from the LMX1A study described above, we are wondering how they are planning to push the cells towards a dopamine fate. If they do not have answers to this issues, they should not be rushing to the clinic with these cells.

So yes, there are reasons for concern regarding the cells that the researchers plan to use in this clinical trial.

And, as with the International Stem Cell Corporation stem cell trial in Australia, we also worry that the follow up-period (or endpoint in the study) of 12 months is not long enough to determine the efficacy of these cells in improving Parkinson’s rating scores and brain imaging results. All of the previous clinical research in this field indicates that the transplanted cells require years of maturation before their dopamine production has an observable impact on the participant. Using 12 months as an end point for this study is tempting a negative result when the long term outcome could be positive.

As we mentioned above, any negative outcomes for these studies could have dire consequences for the field as a whole.

So what does it all mean?

Embryonic stem cells hold huge potential in the field of regenerative medicine. Their ability to become any cell type in the body means that if we can learn how to control them correctly, these cells could represent a fantastic new tool for future cell replacement therapies in conditions like Parkinson’s disease.

Strong demand for such therapies from groups like the Parkinsonian community, has resulted in research groups rushing to the clinic with different approaches using these cells. Concerns as to whether such approaches are ready for the clinic are warranted, if only because mistakes by individual research groups/consortiums in the past have caused delays for everyone in the field.

While China is very keen (and should be encouraged) to take bold steps in its ambition to be a world leader in this field, open and transparent access to extensive preclinical research would help assuage concerns within the research community that prudent care is being taken heading forward.

We’ll keep you aware of developments in this clinical trial.

EDITORIAL NOTE No.1 – It is important for all readers of this post to appreciate that cell transplantation for Parkinson’s disease is still experimental. Anyone declaring otherwise (or selling a procedure based on this approach) should not be trusted. While we appreciate the desperate desire of the Parkinson’s community to treat the disease ‘by any means possible’, bad or poor outcomes at the clinical trial stage for this technology could have serious consequences for the individuals receiving the procedure and negative ramifications for all future research in the stem cell transplantation area.

EDITORIAL NOTE No.2 – the author of this blog is associated with research groups conducting the current Transeuro transplantation trials and the proposed G-Force embryonic stem cell trials planned for 2018. He has endeavoured to present an unbiased coverage of the news surrounding the current clinical trials, though he shares the concerns of the Parkinson’s scientific community that the research supporting the current Australian trial is lacking in its thoroughness and will potentially jeopardise future work in this area. He is also concerned by the lack of peer-reviewed published research on cell transplantation in models of Parkinson’s disease for the proposed clinical studies in China.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Ozy