The general population are wrong to look up to scientists as the holders of the keys to some kind of secret knowledge that allows them to render magic on a semi-irregular basis.

All too often, the great discoveries are made by accident.

A while back, some researchers from Germany and Brazil made an interesting discovery that could have important implications for Parkinson’s disease. But they only made this discovery because their mice were feed the wrong food.

Today we’ll review their research and discuss what it could mean for Parkinson’s disease.

Sir Alexander Fleming. Source: Biography

Sir Alexander Fleming is credited with discovering the antibiotic properties of penicillin.

But, as it is often pointed out, that the discovery was a purely chance event – an accident, if you like.

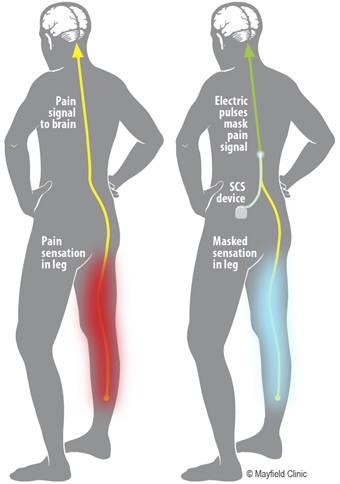

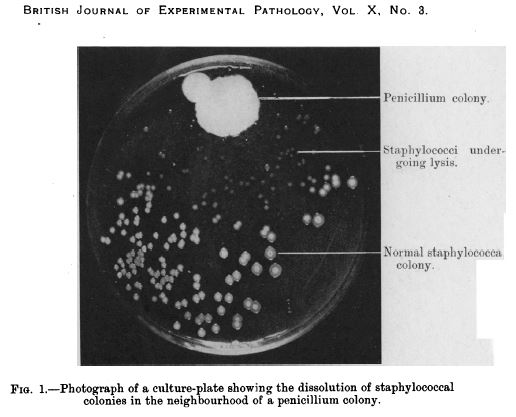

After returning from a two week holiday, Sir Fleming noticed that many of his culture dishes were contaminated with fungus, because he had not stored them properly before leaving. One mould in particular caught his attention, however, as it was growing on a culture plate with the bacteria staphylococcus. Upon closer examination, Fleming noticed that the contaminating fungus prevented the growth of staphylococci.

In an article that Fleming subsequently published in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology in 1929, he wrote, “The staphylococcus colonies became transparent and were obviously undergoing lysis … the broth in which the mould had been grown at room temperature for one to two weeks had acquired marked inhibitory, bactericidal and bacteriolytic properties to many of the more common pathogenic bacteria.”

Penicillin in a culture dish of staphylococci. Source: NCBI

Fleming isolated the organism responsible for prohibiting the growth of the staphylococcus, and identified it as being from the penicillium genus.

He named it penicillin and the rest is history.

Fleming himself appreciated the serendipity of the finding:

“When I woke up just after dawn on Sept. 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionise all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I guess that was exactly what I did.” (Source)

And this gave rise to his famous quote:

“One sometimes finds what one is not looking for” (Source)

While Fleming’s discovery of the antibiotic properties of penicillin was made as he was working on a completely different research problem, the important thing to note is that the discovery was made because the evidence came to a prepared mind.

Pasteur knew the importance of a prepared mind. Source: Thequotes

And this is the purpose of all the training in scientific research – not acquiring ‘the keys to some secret knowledge’, but preparing the investigator to notice the curious deviation.

That’s all really interesting. But what does any of this have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

Three things:

- Serendipity

- Prepared minds

- Antibiotics.

Huh?

Five years ago, a group of Brazilian and German Parkinson’s disease researchers made a serendipitous discovery:

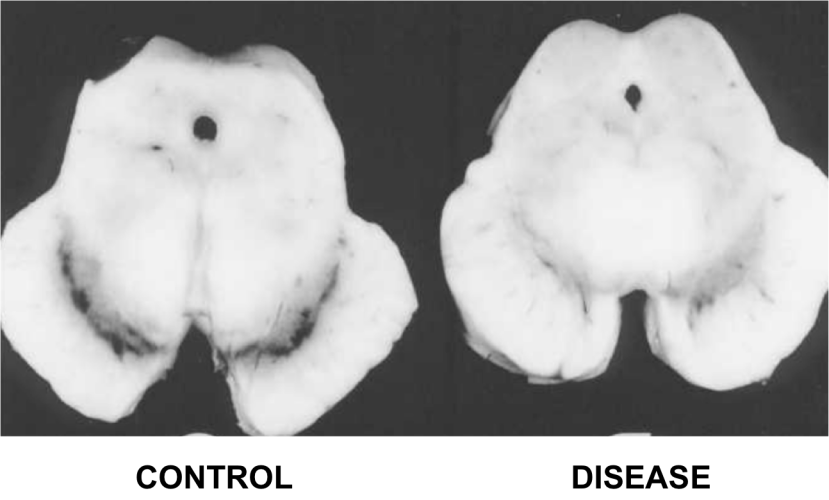

While modelling Parkinson’s disease in some mice, they noticed that only two of the 40 mice that were given a neurotoxic chemical (6-OHDA) developed the motor features of Parkinson’s disease, while the rest remained healthy. This result left them scratching their heads and trying to determine what had gone wrong.

Then it clicked:

“A lab technician realised the mice had mistakenly been fed chow containing doxycycline, so we decided to investigate the hypothesis that it might have protected the neurons.” (from the press release).

The researchers had noted the ‘curious deviation’ and decided to investigate it further.

They repeated the experiment, but this time they added another group of animals which were given doxycycline in low doses (via injection) and fed on normal food (not containing the doxycycline).

And guess what: both group demonstrated neuroprotection!

Hang on a second. Two questions: 1. What exactly is 6-OHDA?

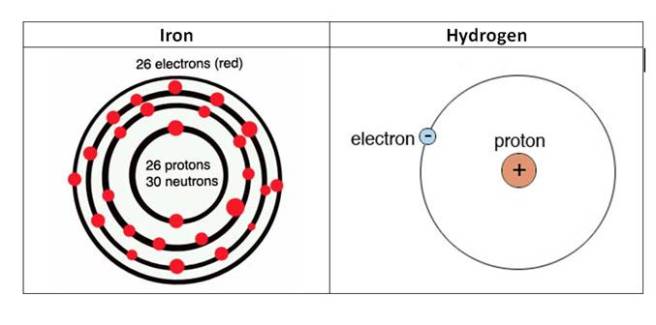

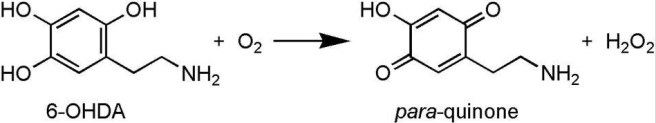

6-hydroxydopamine (or 6-OHDA) is one of several chemicals that researchers use to cause dopamine cells to die in an effort to model the cell death seen in Parkinson’s disease. It shares many structural similarities with the chemical dopamine (which is so severely affected in the Parkinson’s disease brain), and as such it is readily absorbed by dopamine cells who unwittingly assume that they are re-absorbing excess dopamine.

Once inside the cell, 6-OHDA rapidly transforms (via oxidisation) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 – the stuff folk bleach their hair with) and para-quinone (AKA 1,4-Benzoquinone). Neither of which the dopamine neurons like very much. Hydrogen peroxide in particular quickly causes massive levels of ‘oxidative stress’, resulting in the cell dying.

Transformation of the neurotoxin 6-OHDA. Source: NCBI

Think of 6-OHDA as a trojan horse, being absorbed by the cell because it looks like dopamine, only for the cell to work out (too late) that it’s not.

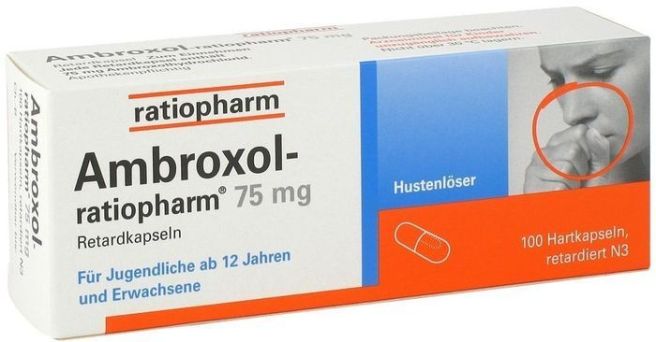

Ok, and question 2. What is doxycycline?

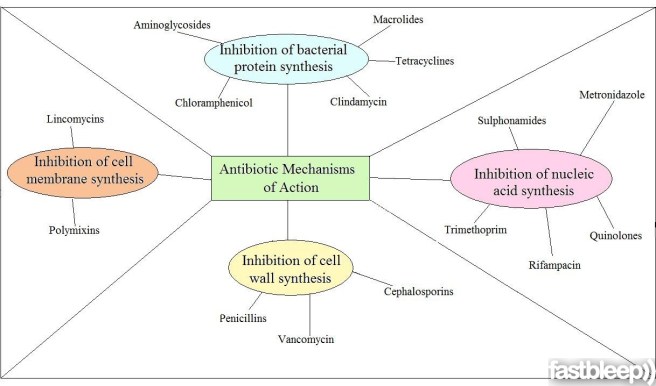

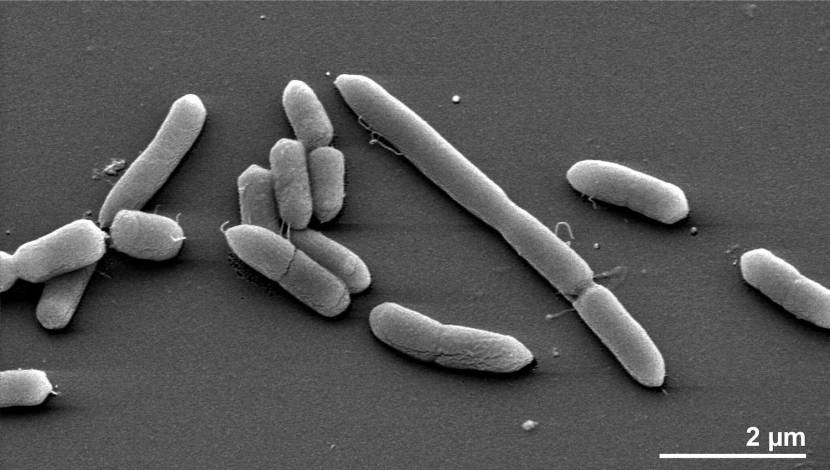

Doxycycline is an antibiotic that is used in the treatment of a number of types of infections caused by bacteria.

Remind me again, what is an antibiotic?

Antibiotics are a class of drugs that either kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria. They function in one of several ways, either blocking the production of bacterial proteins, inhibiting the replication of bacterial DNA (nuclei acid in the image below), or by rupturing/inhibiting the repair of the bacteria’s outer membrane/wall.

The ways antibiotics function. Source: FastBleep

So the researchers accidentally discovered that the a bacteria-killing drug called doxycycline prevented a trojan horse called 6-OHDA from killing dopamine cells?

Basically, yeah.

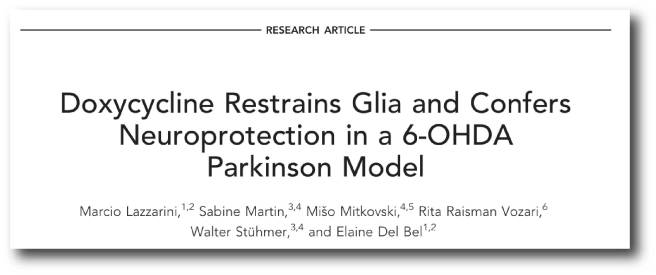

And then these prepared minds followed up this serendipitous discovery with a series of experiments to investigate the phenomenon further, and they published the results recently in the journal ‘Glial’:

Title: Doxycycline restrains glia and confers neuroprotection in a 6-OHDA Parkinson model.

Authors: Lazzarini M, Martin S, Mitkovski M, Vozari RR, Stühmer W, Bel ED.

Journal: Glia. 2013 Jul;61(7):1084-100. doi: 10.1002/glia.22496. Epub 2013 Apr 17.

PMID: 23595698

In the report of their research, the investigators noted that doxycycline significantly protected the dopamine neurons and their nerve branches (called axons) in the striatum – an area of the brain where dopamine is released – when 6-OHDA was given to mice. Both oral administration and peripheral injections of doxycycline were able to have this effect.

They also reported that doxycycline inhibited the activation of astrocytes and microglial cells in the brains of the 6-OHDA treated mice. Astrocytes and microglial cells are usually the helper cells in the brain, but in the context of disease or injury these cells can quickly take on the role of judge and executioner – no longer supporting the neurons, but encouraging them to die. The researchers found that doxycycline reduced the activity of the astrocytes and microglial cells in this alternative role, allowing the dopamine cells to recuperate and survive.

The researchers concluded that the “neuroprotective effect of doxycycline may be useful in preventing or slowing the progression of Parkinson’s disease”.

Wow, was this the first time this neuroprotective effect of doxycycline has been observed?

Curiously, No.

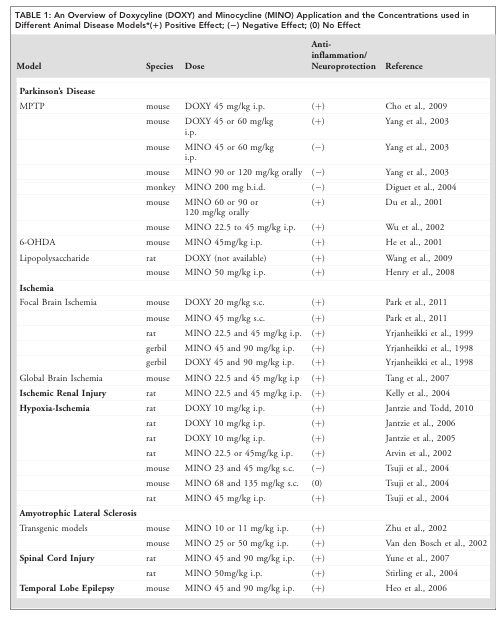

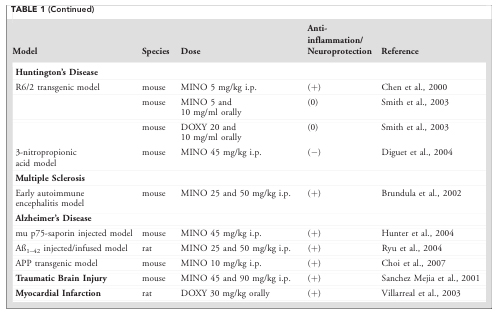

We have known of doxycycline’s neuroprotective effects in different models of brain injury since the 1990s (Click here, here and here for more on this). In fact, in their research report, the German and Brazilian researchers kindly presented a table of all the previous neuroprotective research involving doxycycline:

And there was so much of it that the table carried on to a second page:

Source: Glia

And as you can see from the table, the majority of these reports found that doxycycline treatment had positive neuroprotective effects.

Is doxycycline the only antibiotic that exhibits neuroprotective properties?

No.

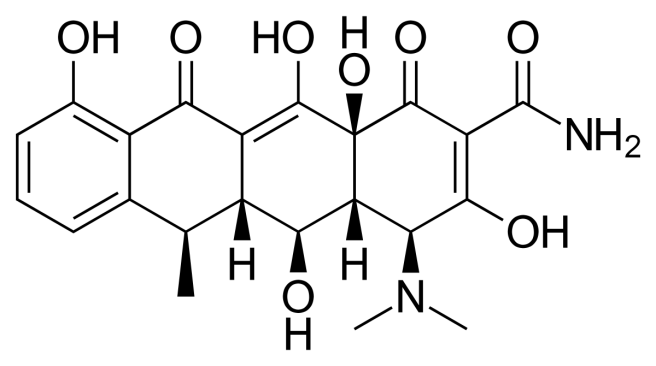

Doxycycline belongs to a family of antibiotics called ‘tetracyclines‘ (named for their four (“tetra-“) hydrocarbon rings (“-cycl-“) derivation (“-ine”)), and other members of this family have also been shown to display neuroprotection in models of Parkinson’s disease:

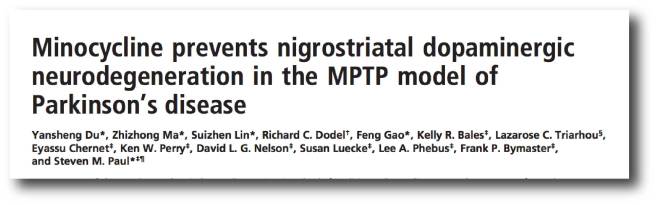

Title: Minocycline prevents nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model ofParkinson’s disease.

Authors: Du Y, Ma Z, Lin S, Dodel RC, Gao F, Bales KR, Triarhou LC, Chernet E, Perry KW, Nelson DL, Luecke S, Phebus LA, Bymaster FP, Paul SM.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Dec 4;98(25):14669-74.

PMID: 11724929 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers treated mice with an antibiotic called minocycline and it protected dopamine cells from the damaging effects of a toxic chemical called MPTP (or 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine). MPTP is also used in models of Parkinson’s disease, as it specifically affects the dopamine cells, while leaving other cells unaffected.

The researchers found that the neuroprotective effect of minocycline is associated a reduction in the activity of proteins that initiate cell death (for example, Caspace 1). This left the investigators concluding that ‘tetracyclines may be effective in preventing or slowing the progression of Parkinson’s disease’.

Importantly, this result was quickly followed by two other research papers with very similar results (Click here and here to read more about this). Thus, it would appear that some members of the tetracycline class of antibiotics share some neuroprotective properties.

So what did the Brazilian and German researchers do next with doxycycline?

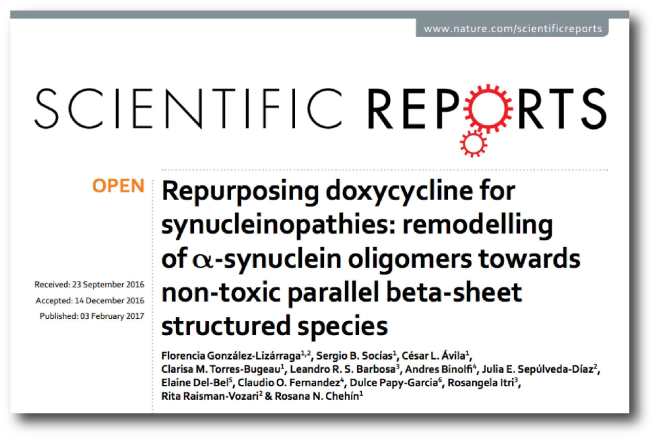

They continued to investigate the neuroprotective effect of doxycycline in different models of Parkinson’s disease. They also got some Argentinians and Frenchies involved in the studies. And these lines of research led to their recent research report in the journal Scientific Reports:

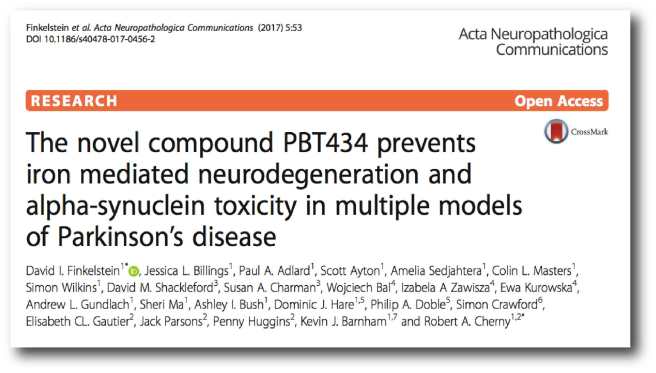

Title: Repurposing doxycycline for synucleinopathies: remodelling of α-synuclein oligomers towards non-toxic parallel beta-sheet structured species.

Authors: González-Lizárraga F, Socías SB, Ávila CL, Torres-Bugeau CM, Barbosa LR, Binolfi A, Sepúlveda-Díaz JE, Del-Bel E, Fernandez CO, Papy-Garcia D, Itri R, Raisman-Vozari R, Chehín RN.

Journal: Sci Rep. 2017 Feb 3;7:41755.

PMID: 28155912 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers wanted to test doxycycline in a more disease-relevant model of Parkinson’s disease. 6-OHDA is great for screening and testing neuroprotective drugs. But given that 6-OHDA is not involved with the underlying pathology of Parkinson’s disease, it does not provide a great measure of how well a drug will do against the disease itself. So, the researchers turned their attention to our old friend, alpha synuclein – the protein which forms the clusters of protein (called Lewy bodies) in the Parkinsonian brain.

What the researchers found was fascinating: Doxycycline was able to inhibit the disease related clustering of alpha synuclein. In fact, by reshaping alpha synuclein into a less toxic version of the protein, doxycycline was able to enhance cell survival. The investigators also conducted a ‘dosing’ experiment to determine the most effect dose and they found that taking doxycycline in sub-antibiotic doses (20–40 mg/day) would be enough to exert neuroprotection. They concluded their study by suggesting that these novel effects of doxycycline could be exploited in Parkinson’s disease by “repurposing an old safe drug”.

Wow, has doxycycline ever been used in clinical trials for brain-related conditions before?

Yes.

From 2005-12,there was a clinical study to determine the safety and efficacy of doxycycline (in combination with Interferon-B-1a) in treating Multiple Sclerosis (Click here for more on this trial). The results of that study were positive and can be found here.

More importantly, the other antibiotic to demonstrate neuroprotection in models of Parkinson’s disease, minocycline (which we mentioned above), has been clinically tested in Parkinson’s disease:

Title: A pilot clinical trial of creatine and minocycline in early Parkinson disease: 18-month results.

Authors: NINDS NET-PD Investigators..

Journal: Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008 May-Jun;31(3):141-50.

PMID: 18520981 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

This research report was the follow up of a 12 month clinical study that can be found by clicking here. The researchers had taken two hundred subjects with Parkinson’s disease and randomly sorted them into the three groups: creatine (an over-the-counter nutritional supplement), minocycline, and placebo (control). All of the participants were diagnosed less than 5 years before the start of the study. At 12 months, both creatine and minocycline were noted as not interfering with the beneficial effects of symptomatic therapy (such as L-dopa), but a worrying trend began with subjects dropping out of the minocycline arm of the study.

At the 18 month time point, approximately 61% creatine-treated subjects had begun to take additional treatments (such as L-dopa) for their symptoms, compared with 62% of the minocycline-treated subjects and 60% placebo-treated subjects. This result suggested that there was no beneficial effect from using either creatine or minocycline in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, as neither exhibited any greater effect than the placebo. In addition, the investigators suggested that the decreased tolerability of minocycline was a concern.

Ok, so where do I sign up for the next doxy clinical trial?

Well, the researchers behind the Scientific reports research (discussed above) are hoping to begin planning clinical trials soon.

But theoretically speaking, there shouldn’t be a trial.

Huh?!?

There’s a good reason why not.

In fact, if you look at the comments section under the research article, a cautionary message has been left by Prof Paul M. Tulkens of the Louvain Drug Research Institute in Belgium. He points out that:

“…using antibiotics at sub-therapeutic doses is the best way to trigger the emergence of resistance (supported by many in vitro and in vivo studies). Using an antibiotic for other indications than an infection caused by a susceptible bacteria is something that should be discouraged”

And he is correct.

We recklessly over use antibiotics all over the world at the moment and they are one of the few lines of defence that we have against the bacterial world. Long term use (which Parkinson’s disease would probably require) of an antibiotic at sub-therapeutic levels will only encourage the rise of antibiotic resistant bacteria (possibly within individuals).

The resistance of bacteria to antibiotics can occur spontaneously via several means (for example, through random genetic mutations during cell division). With the right mutation (inferring antibiotic resistance), an individual bacteria would then have a natural advantage over their friends and it would survive our attempts to kill it with antibiotics. Being resistant to antibiotic would leave that bacteria to wreak havoc upon us.

Its the purest form of natural selection.

How bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. Source: Reactgroup

And antibiotic resistant bacteria are fast becoming a major health issue for us, with the number of species of bacteria developing resistance increasing every year (Click here for a good review on factors contributing to the emergence of resistance, and click here for a review of the antibiotic resistant bacteria ‘crisis’).

But don’t be upset on the Parkinson’s disease side of things. Prof Tulken adds that:

“If doxycycline really acts as the authors propose, the molecular targets are probably very different from those causing antibacterial activity. it should therefore be possible to dissociate these effect from the antibacterial effects and to get active compounds devoid of antibacterial activity This is where research must go to rather than in trying to use doxycycline itself.”

And he is correct again.

Rather than tempting disaster, we need to take the more prudent approach.

Independent researchers must now attempt to replicate the neuroprotective results in carefully controlled conditions. At the same time, chemists should conduct an analysis of the structure of doxycycline to determine which parts of it are having this neuroprotective effect.

The structure of doxycycline. Source: Wikipedia

If researchers can isolate those neuroprotective elements and those same parts are separate from the antibiotic properties, then we may well have another experimental drug for treating Parkinson’s disease.

And the good news is that researchers are already reasonably sure that the mechanisms of the neuroprotective effect of doxycycline are distinct from its antimicrobial action.

So what does it all mean?

Researchers have once again identified an old drug that can perform a new trick.

The bacteria killing antibiotic, doxycycline, has a long history of providing neuroprotection in models of brain disease, but recently researchers have demonstrated that doxycycline may have beneficial effects on particular aspects of Parkinson’s disease.

Given that doxycycline is an antibiotic, we must be cautious in our use of it. It will be interesting to determine which components of doxycycline are neuroprotective, and whether other antibiotics share these components. Given the number of researchers now working in this area, it should not take too long.

We’ll let you know when we hear something.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Under absolutely no circumstances should anyone reading this material consider it medical advice. The material provided here is for educational purposes only. Before considering or attempting any change in your treatment regime, PLEASE consult with your doctor or neurologist. While some of the drugs discussed on this website are clinically available, they may have serious side effects. We therefore urge caution and professional consultation before any attempt to alter a treatment regime. SoPD can not be held responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided here.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Youtube

Hello, this is me – Eirwen Malin. I’m not prepared to own up to quite how many years I worked in the

Hello, this is me – Eirwen Malin. I’m not prepared to own up to quite how many years I worked in the