Recently it has been announced that the Parkinson’s disease-associated gene PARK2 was found to be mutated in 1/3 of all types of tumours analysed in a particular study.

For people with PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease this news has come as a disturbing shock and we have been contacted by several frightened readers asking for clarification.

In today’s post, we put the new research finding into context and discuss what it means for the people with PARK2-associated Parkinson’s disease.

The As, the Gs, the Ts, and the Cs. Source: Cavitt

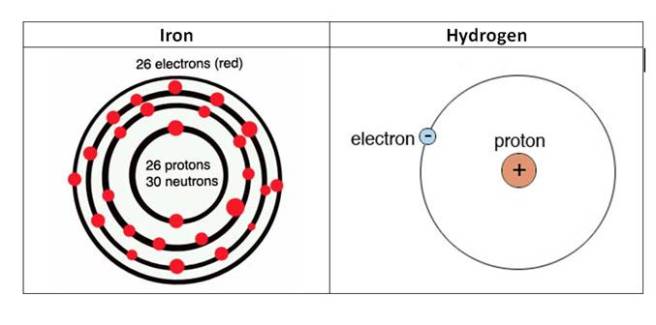

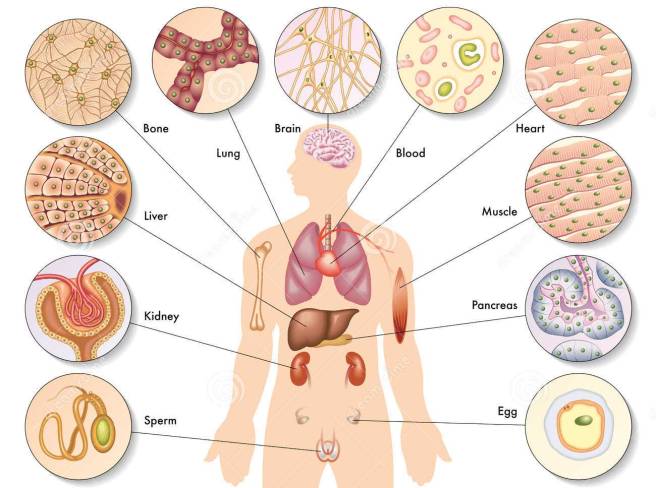

The DNA in almost every cell of your body provides the template for making a human being.

All the necessary information is encoded in that amazing molecule. The basic foundations of that blueprint are the ‘nucleotides’ – which include the familiar A, C, T & Gs – that form pairs (called ‘base pairs’) and which then join together in long strings of DNA that we call ‘chromosomes’.

The basics of genetics. Source: CompoundChem

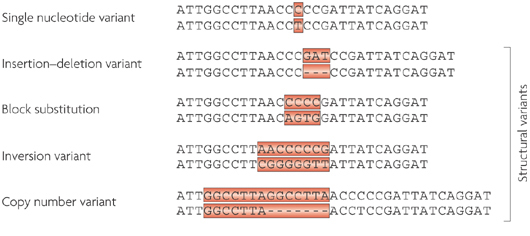

If DNA provides the template for making a human being, however, it is the small variations (or ‘mutations’) in our individual DNA that ultimately makes each of us unique. And these variations come in different flavours: some can simply be a single mismatched base pair (also called a point-mutation or single nucleotide variant), while others are more complicated such as repeating copies of multiple base pairs.

Lots of different types of genetic variations. Source: Nature

Most of the genetic variants that define who we are, we have had since conception, passed down to us from our parents. These are called ‘germ line’ mutations. Other mutations, which we pick up during life and are usually specific to a particular tissue or organ in the body (such as the liver or blood), are called ‘somatic’ mutations.

Somatic vs germ line mutations. Source: AutismScienceFoundation

In the case of germ line mutations, there are several sorts. A variant that has to be provided by both the parents for a condition to develop, is called an ‘autosomal recessive‘ variant; while in other cases only one copy of the variant – provided by just one of the parents – is needed for a condition to appear. This is called an ‘autosomal dominant’ condition.

Autosomal dominant vs recessive. Source: Wikipedia

Many of these tiny genetic changes infer benefits, while other variants can result in changes that are of a more serious nature.

What does genetics have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

Approximately 15% of people with Parkinson disease have a family history of the condition – a grandfather, an aunt or cousin. For a long time researchers have noted this familial trend and suspected that genetics may play a role in the condition.

About 10-20% of Parkinson’s disease cases can be accounted for by genetic variations that infer a higher risk of developing the condition. In people with ‘juvenile-onset’ (diagnosed under the age 20) or ‘early-onset’ Parkinson’s disease (diagnosed under the age 40), genetic variations can account for the majority of cases, while in later onset cases (>40 years of age) the frequency of genetic variations is more variable.

For a very good review of the genetics of Parkinson’s disease – click here.

There are definitely regions of DNA in which genetic variations can increase one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. These regions are referred to as ‘PARK genes’.

What are PARK genes?

We currently know of 23 regions of DNA that contain mutations associated with increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. As a result, these areas of the DNA have been given the name of ‘PARK genes’.

The region does not always refer to a particular gene, for example in the case of our old friend alpha synuclein, there are two PARK gene regions within the stretch of DNA that encodes alpha synuclein – that is to say, two PARK genes within the alpha synuclein gene. So please don’t think of each PARK genes as one particular gene.

There can also be multiple genetic variations within a PARK gene that can increase the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The increased risk is not always the result of one particular mutation within a PARK gene region (Note: this is important to remember when considering the research report we will review below).

In addition, some of the mutations within a PARK gene can be associated with increased risk of other conditions in addition to Parkinson’s disease.

And this brings us to the research report that today’s post is focused on.

One of the PARK genes (PARK2) has recently been in the news because it was reported that mutations within PARK2 were found in 2/3 of the cancer tumours analysed in the study.

Here is the research report:

Title: PARK2 Depletion Connects Energy and Oxidative Stress to PI3K/Akt Activation via PTEN S-Nitrosylation

Authors: Gupta A, Anjomani-Virmouni S, Koundouros N, Dimitriadi M, Choo-Wing R, Valle A, Zheng Y, Chiu YH, Agnihotri S, Zadeh G, Asara JM, Anastasiou D, Arends MJ, Cantley LC, Poulogiannis G

Journal: Molecular Cell, (2017) 65, 6, 999–1013

PMID: 28306514 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

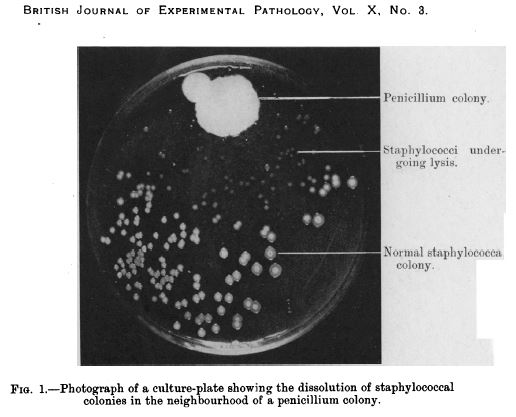

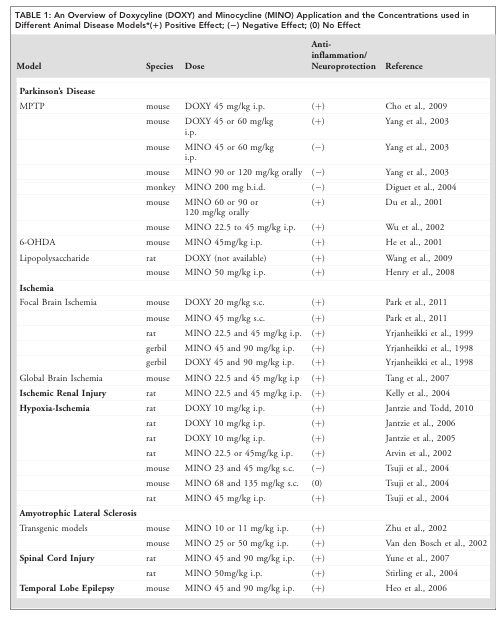

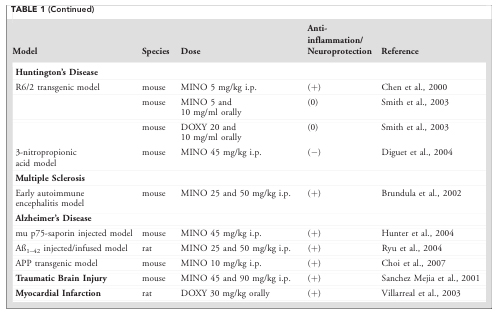

The investigators who conducted this study had previously found that mutations in the PARK2 gene could cause cancer in mice (Click here to read that report). To follow up this research, they decided to screen the DNA from a large number of tumours (more than 20,000 individual samples from at least 28 different types of tumours) for mutations within the PARK2 region.

Remarkably, they found that approximately 30% of the samples had PARK2 mutations!

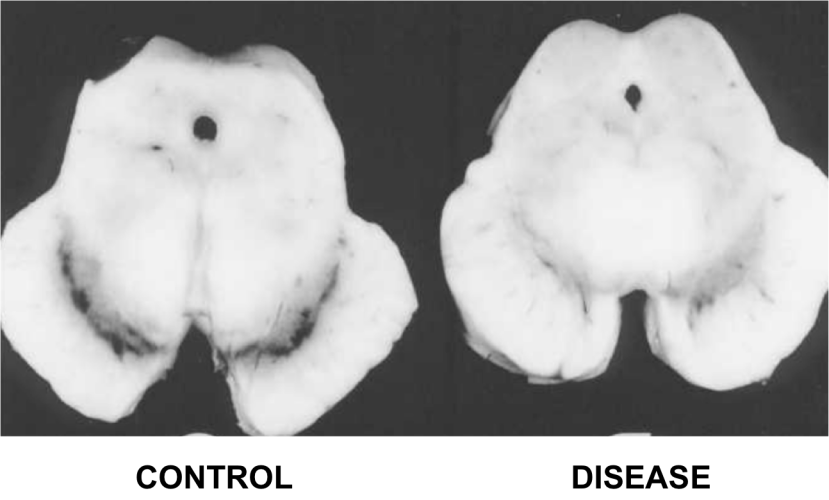

In the case of lung adenocarcinomas, melanomas, bladder, ovarian, and pancreatic, more than 40% of the samples exhibited genetic variations related to PARK2. And other tumour samples had significantly reduced levels of PARK2 RNA. For example, two-thirds of glioma tumours had significantly reduced levels of PARK2 RNA.

Hang on a second, what is PARK2?

PARK2 is a region of DNA that has been associated with Parkinson’s disease. It lies on chromosome 6. You may recall from high school science class that a chromosomes is a section of our DNA, tightly wound up to make storage in cells a lot easier. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes.

Several genes fall within the PARK2 region, but most of them are none-protein-coding genes (meaning that they do not give rise to proteins). The PARK2 region does produce a protein, which is called Parkin.

The location of PARK2. Source: Atlasgeneticsoncology

Particular genetic variants within the PARK2 regions result in an autosomal recessive early-onset form of Parkinson disease (diagnosed before 40 years of age). One recent study suggested that as many as half of the people with early-onset Parkinson’s disease have a PARK2 variation.

Click here for a good review of PARK2-related Parkinson’s disease.

Ok, so if PARK2 was about Parkinson’s disease, what is it doing in cancer?

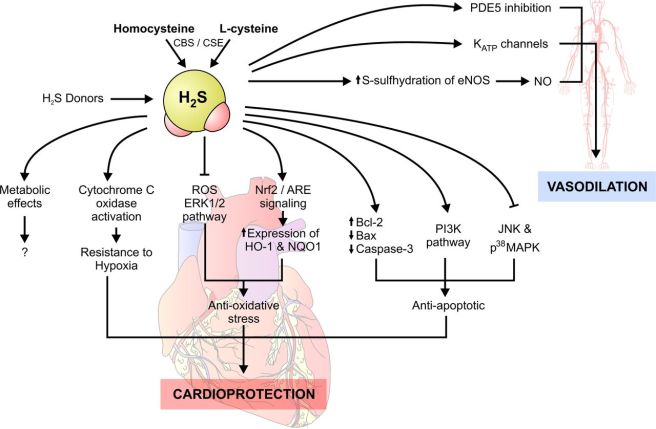

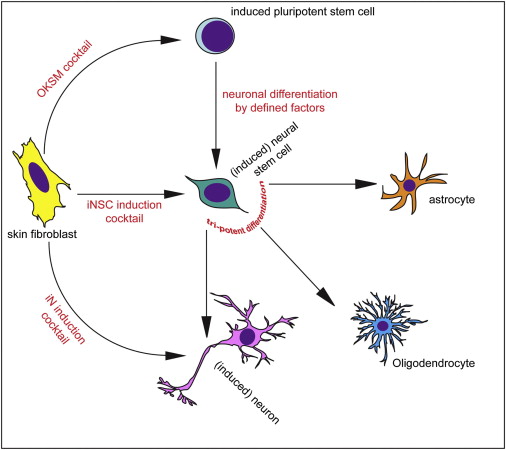

In Parkinson’s disease, Parkin – the protein of PARK2 – is involved with the removal/recycling of rubbish from the cell. But Parkin has also been found to have other functions. Of particular interest is the ability of Parkin to encourage dividing cells to…well, stop dividing. We do not see this function in neurons, because neurons do not divide. In rapidly dividing cells, however, Parkin can apparently stop the cells from dividing:

Title: Parkin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in TNF-α-treated HeLa cells

Authors: Lee MH, Cho Y, Jung BC, Kim SH, Kang YW, Pan CH, Rhee KJ, Kim YS.

Journal: Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Aug 14;464(1):63-9.

PMID: 26036576

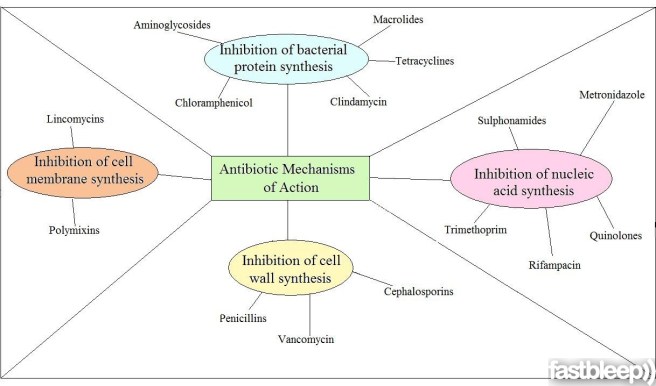

This discovery made researchers re-designate PARK2 as a ‘tumour suppressor‘ – a gene that encodes a protein which can block the development of tumours. Now, if there is a genetic variant within a tumour suppressor – such as PARK2 – that blocks it from stopping dividing cells, there is the possibility of the cells continuing to divide and developing into a tumour.

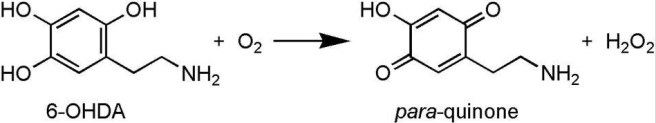

Without a properly functioning Parkin protein, rapidly dividing cells may just keep on dividing, encouraging the growth of a tumour.

Interestingly, the reintroduction of Parkin into cancer cells results in the death of those cells – click here to read more on this.

Oh no, I have a PARK2 mutation! Does this mean I am going to get cancer?

No.

Let us be very clear: It does not mean you are ‘going to get cancer’.

And there are two good reasons why not:

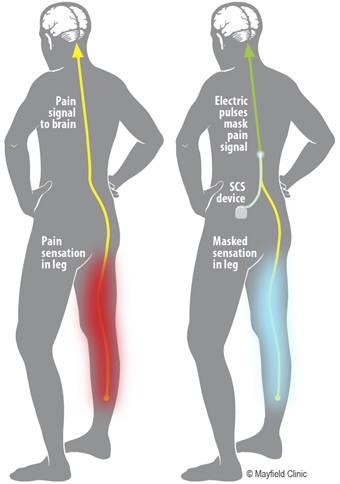

Firstly, location, location, location – everything depends on where in the Parkin gene a mutation actually lies. There are 10 common mutations in the Parkin gene that can give rise to early-onset Parkinson’s disease, but only two of these are associated with an increased risk of cancer (they are R24P and R275W – red+black arrow heads in the image below – click here to read more about this).

Comparing PARK2 Cancer and PD associated mutations. Source: Nature

Parkin (PARK2) is one of the largest genes in humans (of the 24,000 protein encoding genes we have, only 18 are larger than Parkin). And while size does not really matter with regards to genetic mutations and cancer (the actual associated functions of a gene are more critical), given the size of Parkin it isn’t really surprising that it has a high number of trouble making mutations. But only two of the 13 cancer causing mutations are related to Parkinson’s.

Thus it is important to beware of exactly where your mutation is on the gene.

Second, in general, people with Parkinson’s disease actually have a 20-30% decreased risk of cancer (after you exclude melanoma, for which there is an significant increased risk and everyone in the community should be on the lookout for). There are approximately 140 genes that can promote or ‘drive’ tumour formation. But a typical tumour requires mutations in two to more of these “driver gene” for a tumour to actually develop. Thus a Parkin cancer-related mutation alone is very unlikely to cause cancer by itself.

So please relax.

The new research published this week is interesting, but it does not automatically mean people with a PARK2 mutation will get cancer.

What does it all mean?

So, summing up: Small variations in our DNA can play an important role in our risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Some of those Parkinson’s associated variations can also infer risk of developing other diseases, such as cancer.

Recently new research suggested that genetic variations in a Parkinson’s associated genetic region called PARK2 (or Parkin) are found in many forms of cancer. While the results of this research are very interesting, in isolation this information is not useful except in frightening people with PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease. Cancers are very complex. The location of a mutation within a gene is important and generally more than cancer-related gene needs to be mutated before a tumour will develop.

The media needs to be more careful with how they disseminate this information from new research reports. People who are aware that they have a particular genetic variation will be sensitive to any new information related to that genetic region. They will only naturally take the news badly if it is not put into proper context.

So to the frightened PARK2 readers who contacted us requesting clarification, firstly: keep calm and carry on. Second, ask your physician about where exactly your PARK2 variation is exactly within the gene. If you require more information from that point on, we’ll be happy to help.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Ilovegrowingmarijuana