|

# # # # Levodopa is a key ingredient in the production of dopamine. As such it is used as a treatment for people with Parkinson’s to help replace levels of dopamine in the brain. For a long time, the production of dopamine was believed to be the only function of levodopa. But recently, researchers have discovered that levodopa is doing other things in cells, when the dopamine production pathway is blocked. And their investigations are providing new insights into the brain mechanisms of movement and pointing towards alternative routes to symptomatically treat Parkinson’s. In today’s post, we will review new research introducing ophthalmic acid (or ophthalmate) to the world of Parkinson’s research. # # # # |

Source: Sciencesocks

Source: Sciencesocks

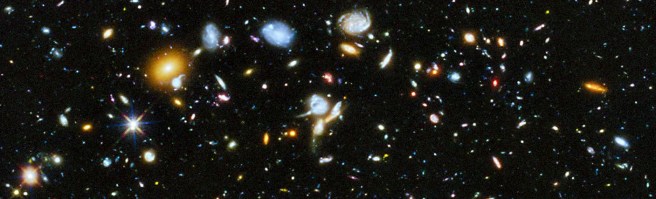

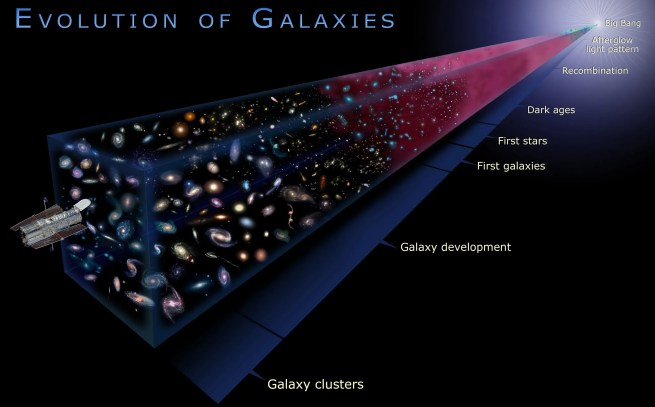

Between December 18th and 28th, 1995, researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to take 342 images of a tiny “keyhole” region of the universe (just 1/24 millionth of the whole sky).

The project was called the Hubble Deep Field (or HDF) and it provided the most detailed image of a small region in the constellation Ursa Major (“Great Bear”) ever taken.

Ursa Major (HDF is the pin-hole spot that was imaged).Source: Firstpr

Ursa Major (HDF is the pin-hole spot that was imaged).Source: Firstpr

The most shocking detail of that collection of images was that there are over 3,000 objects in them, and all of them were galaxies (similar to our Milky way).

3,000 galaxies (not stars, but galaxies!) in just 1/24 millionth of the whole sky!

Three years later, a similar sized region in the south hemisphere was imaged. That project was called the Hubble Deep Field South and it gave the same results (thousands of galaxies in a tiny fragment of the sky), strengthened the belief that the universe is largely uniform.

Source: NASA

Source: NASA

The data led to estimates that there could be as many as 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe (Source).

Interesting intro. Is this post going to be about aliens? Aliens with Parkinson’s?

No.

One of the really wonderful aspects of science is the ‘paradigm shifting finding’. A new insight that shakes the “what we think we know” stuff.

Much of science is iterative: Hypothesis testing, that leads to new hypotheses that need to be tested, trial and error, and so forth. But every now and then during that process, a finding pops up that grabs the attention and shifts the focus.

And recently, just such a result was reported by scientists at the University of California Irvine.

What did they find?

Well, the researchers wanted to investigate the different functions of levodopa, beyond its role in the production of dopamine and other neurotransmitters.

Remind me, what is levodopa?

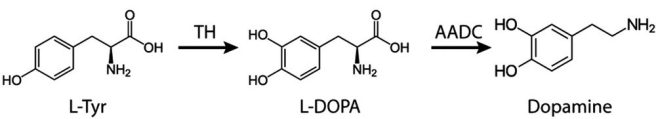

Very quickly, levodopa (also known as L-DOPA) is the essential ingredient for several neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) including dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline). It is produced from the amino acid l-tyrosine (L-Tyr), by an enzyme called tyrosine hydroxylase (TH).

The production of dopamine. Source: Wiley

The production of dopamine. Source: Wiley

Parkinson’s is characterised by the loss of dopamine neurons in the brain and the primary means of treating the condition is to replace the lost dopamine by administering levodopa tablets to boost dopamine production.

When you take an levodopa tablet, the pill will be broken down in your stomach and the levodopa will enter your blood through the intestinal wall. Via your bloodstream, it arrives in the brain where it will be absorbed by cells. Inside the cells, another chemical (called DOPA decarboxylase) then changes it into dopamine. That newly produced dopamine helps to replace the missing dopamine in the brain and alleviate the motor features of Parkinson’s (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about levodopa).

Ok, so levodopa is involved with dopamine production. Why were the researchers looking for other functions?

Well, there aren’t many “single function” proteins/chemicals in the body, and we shouldn’t just assume that in a complex system each component only has one function. And if levodopa does have other functions, it might be useful to know what it does given that people with Parkinson’s are being treated with it.

So the University of California Irvine researchers started exploring what other functions levodopa has inside of cells. They did this by blocking the production of dopamine, while administering levodopa.

And what they found was rather…. well, strange.

What do you mean strange?

Ok, so by blocking DOPA decarboxylase activity – the enzyme that converts levodopa to dopamine – they should stop the production of dopamine. Right?

Yep, that much I understand.

And by blocking DOPA decarboxylase activity in a rodent model of Parkinson’s, the animals should have a lot of trouble being able to move because there will be very little dopamine being produced.

No dopamine, no movement.

That too is understood. So what was so strange about their findings?

Well, in their previous research, the researchers treated the animals with a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (which blocked levodopa conversion to dopamine every where in the body, including the brain) and….

And what?

The animals became hyperactive.

Que???

Yeah, and it gets even stranger: The onset of the hyperactive motor activity induced by the administration of levodopa and DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (named NSD1015) was delayed.

The hyperactivity began about 2 hours after treatment, compared to just 45 minutes for levodopa alone. And the excessive mobility in the levodopa + NSD1015 treated animals lasted for a prolonged duration of time (much longer than levodopa by itself).

And wait, there’s more.

The hyperactivity was about 7-fold more than in the control animals that were treated with just levodopa (that is to say, the control animals were Parkinson’s models, but they were treated with just levodopa. So they had normal levels of dopamine production).

????? How is any of that possible?

Well, the researchers explored some of the ‘how’ in that first study, and the results were published in this paper:

Title: Locomotor response to L-DOPA in reserpine-treated rats following central inhibition of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase: further evidence for non-dopaminergic actions of L-DOPA and its metabolites.

Title: Locomotor response to L-DOPA in reserpine-treated rats following central inhibition of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase: further evidence for non-dopaminergic actions of L-DOPA and its metabolites.

Authors: Alachkar A, Brotchie JM, Jones OT.

Journal: Neurosci Res. 2010 Sep;68(1):44-50.

PMID: 20542064

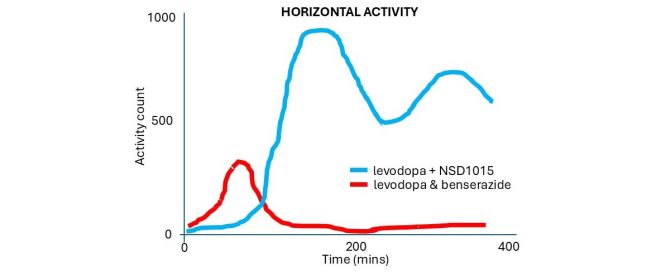

In this study, the researchers modelled Parkinson’s in rodents using a drug called reserpine. Eighteen hours later, they treated the animals with either:

- Levodopa & a peripherally acting DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (named benserazide) or,

- Levodopa & a broad DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (named NSD1015)

About 40 minutes later, the levodopa & benserazide group began moving around like normal, but the levodopa + NSD1015 treated animals remained immobile. Then as the effect of the levodopa & benserazide treatment was wearing off in the first groups, the levodopa + NSD1015 group suddenly came to life, and… well, they became really active:

(An accurate representation of the data – the author of this blog is trying not to break anymore copyright laws)

(An accurate representation of the data – the author of this blog is trying not to break anymore copyright laws)

And as I wrote above, you can see in the graph here that the delayed hyperactivity of the levodopa + NSD1015 treated animals was higher and lasted longer than that of the levodopa & benserazide group.

The researchers attempted to determine the mechanism of action involved with this strange hyperactivity. They firstly looked at dopamine function. Dopamine works as a neurotransmitter by binding to structures on the surface of cells called dopamine receptors, but when the researchers used drugs to block the dopamine receptors it had no effect on the hyperactivity they were observing. So they decided that the levodopa + NSD1015 hyperactivity was not occurring via dopamine function.

Next they looked at several other receptors (such as the adrenergic receptor and serotonergic receptors). Blocking these slightly reduced the hyperactive effect, but the researchers were left without a strong answer to what was causing the hyperactivity.

And that led to the new research report that has just been published:

Title: Ophthalmate is a new regulator of motor functions via CaSR: implications for movement disorders.

Title: Ophthalmate is a new regulator of motor functions via CaSR: implications for movement disorders.

Authors: Alhassen S, Hogenkamp D, Nguyen HA, Al Masri S, Abbott GW, Civelli O, Alachkar A.

Journal: Brain. 2024 Oct 3;147(10):3379-3394.

PMID: 38537648

In this new report, the researchers replicated their previous rodent work, but this time in a mouse model of Parkinson’s. And they found the same effect: In mice treated with levodopa and NSD1015, there was a delayed increase in mobility that began about 2 hours after treatment and was sustained for a longer duration than that induced by levodopa alone.

Next to determine if the effect was specific to levodopa, the investigators tested dopamine receptor agents in their NSD1015 treated mouse Parkinson’s model, and they found that these agents had no effect on the hyperactivity, so they concluded that the NSD1015-associated hyperactivity is linked to levodopa, but not dopamine.

Next to determine if the effect was specific to levodopa, the investigators tested dopamine receptor agents in their NSD1015 treated mouse Parkinson’s model, and they found that these agents had no effect on the hyperactivity, so they concluded that the NSD1015-associated hyperactivity is linked to levodopa, but not dopamine.

To try and identify the mechanism of action in this effect, the researchers analysed what proteins are elevated or decreased during levodopa and NSD1015 treatment.

And this is where they discovered that levels of ophthalmate levels rose 20-fold in levodopa and NSD1015-treated mice (compared to pretreatment measurements) and this was an 8-fold increase relative to levodopa & benserazide-treated mice.

What is ophthalmate?

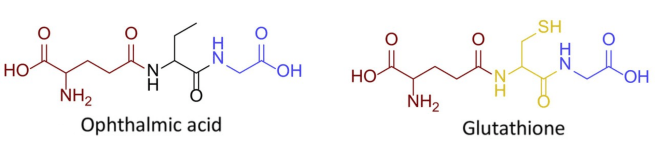

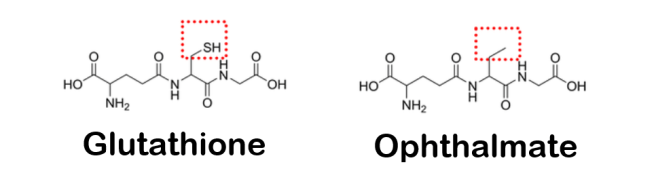

Also known as ophthalmic acid, ophthalmate is an analog (or a compound that has a similar structure) of glutathione.

And what is glutathione?

First discovered in cows back in 1958, glutathione is recognised as a powerful antioxidant in the body. It is made from the amino acids glycine, cysteine, and glutamic acid, and when compared to ophthalmic acid, the two molecules are very similar:

Very similar molecules. Source: FEBS

Very similar molecules. Source: FEBS

To assess if the observed hyperactivity following levodopa/NSD1015 treatment in the mouse Parkinson’s model was directly caused by elevated ophthalmate levels, the investigators treated their mouse Parkinson’s model with ophthalmate, and…

…..

…..

(stretching the suspense here)…

…found that it enhanced motor activity in these mice in a dose-dependent manner (the higher the dose, the more activity).

Incredibly, the enhanced motor activity of ophthalmate treatment persisted for around 24 hours, peaking during the first 10 hours.

A key detail here is that the investigators had to deliver ophthalmate directly into the brain to see the effect, because they found that ophthalmate could not cross the blood brain barrier (the protective membrane surrounding the brain). This finding also suggests that the hyperactivity observed in the levodopa/NSD1015 treated animals was the result of ophthalmate produced in the brain, as opposed to somewhere else in the body.

Interesting. So how was ophthalmate having its effect?

Given the structural similarities between ophthalmate and glutathione, the researchers turned their attention to the calcium-sensing receptor, which is known to be modulated by glutathione.

What is the Calcium-sensing receptor?

It is a protein that monitors and regulates the amount of calcium in the blood. It is a G-protein coupled receptor that is found in the parathyroid gland, the kidneys, and the brain.

Calcium-sensing receptor. Source: Cambridge

Calcium-sensing receptor. Source: Cambridge

The investigators found that ophthalmate binds to the calcium-sensing receptor, and when they treated their animals with a CaSR inhibitor, the motor-enhancing effects of levodopa & NSD1015 were suppressed.

So is the effect dependent on levodopa?

Yes, the researchers found that “both the intensity and duration of the motor activity strongly correlate with levodopa doses”.

But it is independent of dopamine?

Yes.

Has anyone ever found this before?

Actually? Yes.

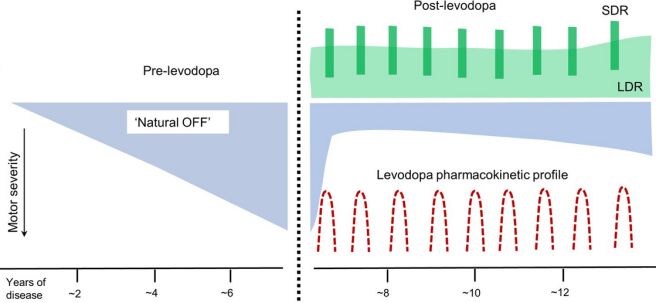

In fact, not long after the early pilot studies with levodopa in the 1960s (Click here to read a SoPD post about that) researchers noticed two phases in the response to levodopa, one of ‘short duration’ (which is the bedrock of the modern treatment response) and another of ‘long-duration’ (which “is active beyond the elimination of levodopa, declining to baseline days to weeks after” (for those interested, Profs

The long-duration response of levodopa isn’t really noticed by the individual being treated with the drug, as they are repeatedly taking levodopa which masks the longer term effect. But the long-duration response in humans is also not as dramatic as the one that was observed in the preclinical studies discussed above. Rather, in humans, it is a more subtle effect. Basically, people with Parkinson’s taking levodopa don’t return to their previous pre-treatment baseline, but rather something slightly more elevated:

Dashed line = initiation of levodopa treatment; SDR=Short duration response; LDR=Long duration response. Source:

Dashed line = initiation of levodopa treatment; SDR=Short duration response; LDR=Long duration response. Source:

The mechanism of this long-duration response has never been determined, which is why this new data is so interesting.

Very good. So what does it all mean?

Mmmm, before we sum up there is another aspect to this that needs to be discussed.

It deals with the relationship between ophthalmate and glutathione.

What is the relationship between ophthalmate and glutathione like?

Well, the production of both glutathione and ophthalmate involve common enzymes (such as glutamate-cysteine synthase and glutathione synthase – click here for a useful review on this relationship).

For a long time, it has been recognised that glutathione is reduced in the substantia nigra region of the brain (where the dopamine neurons reside) in people with Parkinson’s. And this decrease in glutathione levels does not occur in other brain regions in Parkinson’s, nor does it occur in this brain region in other neurodegenerative condition (such as multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy – click here, here and here to read some examples of this research).

So it could be that early in the development of Parkinson’s, in addition to the gradual loss of dopamine neurons, there could be a shift in the brain towards production of ophthalmate as a compensatory measure to support dopamine depleted motion. This shift would have consequences, however, as glutathione is an important anti-oxidant.

But I am just speculating here.

So what does it all mean?

Historically, dopamine has been central to our understanding of movement. Based on its reduction in the Parkinsonian brain and the ability of levodopa treatment to restore motion, dopamine has been the focus of all of the attention. Only recently have other neural pathways been found to be critically involved in our ability to move (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on one such pathway). It is exciting and absolutely fascinating to find that levodopa could be moonlighting in a secondary career, somehow being involved in the activation of other pathways influencing movement.

It is also important for the future treatment of Parkinson’s to better understand these other pathways, and determine if they can be modulated in some way that has less treatment-associated complications (think: dyskinesias). While there are still many facets of this research to unravel and iron out, it is really intriguing and I look forward to watching for future developments – crucially, independent replication.

# # # # # # # #

We started this post with a cosmic view of things, but I would like to end it on a more down-to-Earth note. Long time readers know that I like to understand the context behind the research and with that in mind, I would like to shine a light on the lead scientist on both of the papers discussed here today: Dr. Amal Alachkar.

Dr. Amal Alachkar. Source: IIe

Dr. Amal Alachkar. Source: IIe

She is an Institute of International Education Scholar Rescue Fund alumna and former Hubert H. Humphrey Program Fellow who works at the University of California Irvine. Dr. Alachkar graduated from the Aleppo University School of Pharmacy in 1996, before going to the University of Liverpool to do a PhD in neuroscience.

She returned to the Aleppo University School of Pharmacy in 2004, where she established the first neuroscience research lab in Syria. The 2010 paper that found the initial levodopa effect was published while Dr. Alachkar was still affiliated with Aleppo University, but the Arab Spring and subsequent civil war in her home country led her to join UC Irvine as a professor in 2012.

There are tales behind all of the research we discuss here. When reading their reports, we have little insight into the stories of the researchers who dedicate their lives to helping us better understand the brain and the diseases that affect it. I suspect that the journey Prof Alachkar has been on to get this research conducted and published may have been more challenging than most.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from FEBS

Simon, I doubt you are aware but your jockular comment on “aliens with Parkinson’s” does have scientific relevance. There are many reprts of witnesses to UFO close encounters who are ‘paralysed’ remotely by UFO occupnat humanoids. They remain standing, balanced and aware, but able only to move their eye muscles, for periods of several minutes.

LikeLike

So, in humans, the long term effect of levodopa may keep us from going too off, but may cause dyskinesia as well? “May,” “may.”

LikeLike

Simon, you rock! I have PD and am a newly retired physician I could not get anyone in my boxing crowd or medical community to share my crazed enthusiasm last October when I first read about Opthalmate. Yes, discovered in 1950s with higher amounts in the calves eyeballs… but medical school in the late 1980s early 90s? I heard nothing about it. Zero. I am therefore wildly interested in what we will see in coming years. I hope you remain our skilled research interpreter – for us with more clinical and practical understanding.

-Richard

LikeLike

Hi Richard,

Thanks for your kind comment. Glad you liked the post. I agree the Opthalmate work is really interesting, and like you I look forward to seeing what becomes of it.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike