|

# # # # It is exciting when new research comes along that reframes how we might look at a problem. New research published this week has done just that for Parkinson’s. Researchers have analysed vast amounts of brain imaging data and found that it points towards a hyperconnectivity between Parkinson’s associated structures within the brain. They also found that current treatment approaches help to reduce this hyperconnectivity. Using this data, the researchers conducted a clinical trial that further supports their paradigm shifting results. In today’s post, we will discuss what exactly they have discovered, why it is important, and how it could change how we view Parkinson’s. # # # # |

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

This is a photo of a young Wilder Graves Penfield.

He was 22 years old when this photo was taken in 1913. Playing/coaching football at Princeton, with a truly remarkable life still ahead of him.

Remarkable how?

Remarkable as in ‘eventful’.

For example, in 1915 he obtained a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, where he studied neuropathology with the greats like Sir Charles Scott Sherrington and William Osler, before he got pulled into World War I and went to France to serve as a dresser in a military hospital. He was wounded however when the boat he was aboard was torpedoed, and after recovering from his injuries he married his wife. He began studying medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, attaining his degree in 1918. All of that in just three years!

But his life was also remarkable in what he achieved in his research.

What did he do in research?

To put it very simply: He mapped out large parts of the brain.

Can you put it less simply? What exactly did he do?

He trained as a neurosurgeon and in 1934, he moved to Canada to become the first director of the Montreal Neurological Institute (now the Neuro) at McGill University. While working with his colleague Herbert Jasper, he developed the “Montréal Procedure” in which he treated severe epilepsy patients by destroying the regions of the brain where the seizures originated. This operation involved patients being conscious (under only local anesthesia) while areas were stimulated.

This stimulation of the brain in conscious patients allowed Penfield and colleagues to create maps of the sensory and motor cortices of the human brain.

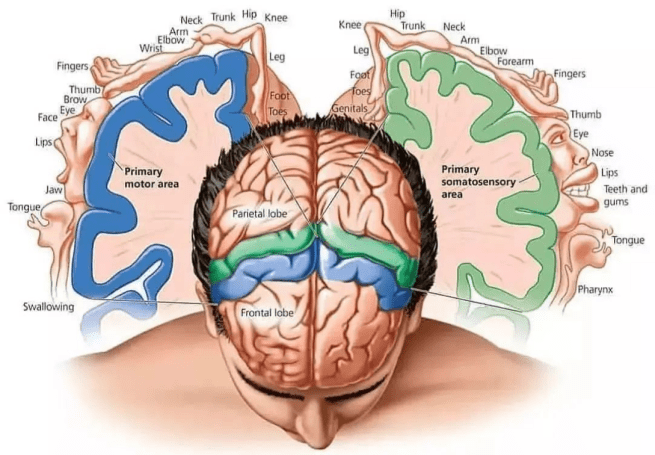

What are the sensory and motor cortices?

They are two parallel bands of the cortex of our brains. In the image below, the sensory cortex of the brain is represented by the blue area, while the motor cortex is represented by the orange area:

Source: Newscientist

Source: Newscientist

Penfield and team started publishing some of their “mapping” findings in this 1937 report:

Title: Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation.

Authors: Penfield W, Boldrey E.

Journal: Brain 1937; 60: 389–440.

PMID: N/A

By stimulating different areas of the brains of patients undergoing surgery to control their epilepsy, Penfield and colleagues were able to produce topographical maps demonstrating that certain areas of the motor and sensory cortices were specific to particular regions of the body:

The topographical maps of function in the sensory (green) and motor (blue) cortices Source: Instagram

The topographical maps of function in the sensory (green) and motor (blue) cortices Source: Instagram

The stimulation that they applied to the cortex would elicit an action or a feeling in particular parts of the body. This research led to the idea of the “cortical homunculus“:

The cortical homunculus. Source: Researchgate

The cortical homunculus. Source: Researchgate

And they didn’t stop there. Penfield and colleagues stimulated the temporal lobes of the brain and found that this led to the vivid recall of memories (Source).

For the purpose of today’s post, we are just going to stay focused on motor cortex, but for those wanting to learn more about Wilder Penfield, this old video might be of interest:

And you really should read the story about how Penfield conducted surgery on his own sister’s brain tumor (Click here to read that story).

So the motor cortex must be important for Parkinson’s, right?

It is fair to say that the motor cortex has been in the shadow of other structures deeper in the brain that have exhibited more signs of pathology. I am thinking of regions like the substantia nigra, where the loss of dopamine neurons is very apparent.

But yes, the motor cortex is important to Parkinson’s, and we’ll come back to this topic in one moment.

First though, it is important to understand that our knowledge of Penfield’s topographical map of the motor cortex has advanced and changed slightly with time.

Changed how?

Well, for years after the original reports of the topographical map of the motor cortex were put forward by Penfield and colleagues, researchers have been pointing out that the seamless map of the body across the motor cortex does not appear to be so seamless. Penfield himself observed considerable overlap between regions of the motor cortex. For example, the areas controlling muscles in the hand would sometimes also control muscles in the shoulder. Penfield put this phenomenon down to individual variations.

Other researchers, however, dug deeper and found that the brain is not so simple that there is a perfectly mapped orderly continuum for motor function stretched across the surface of the cortex..

For example in 1978, this report was published:

Title: Spatial organization of precentral cortex in awake primates. II. Motor outputs.

Title: Spatial organization of precentral cortex in awake primates. II. Motor outputs.

Authors: Kwan HC, MacKay WA, Murphy JT, Wong YC.

Journal: J Neurophysiol. 1978 Sep;41(5):1120-31.

PMID: 100584

In this study, the investigators found that in non-human primates the motor cortex map was divided into concentric zones instead of a continuous stripe. In this fashion, the areas responsible for fingers might be surrounded by areas for the wrists, elbows, then shoulders.

Other reports found that some areas of the motor cortex did not prompt muscle movements at all. Instead, those areas connected to brain areas controlling other functions.

The findings of overlapping and fractured structure in the motor cortex suggested to researchers that further investigation was required.

And then in 2023, this report was published:

Title: A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex.

Title: A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex.

Authors: Gordon EM, Chauvin RJ, Van AN, Rajesh A, Nielsen A, Newbold DJ, Lynch CJ, Seider NA, Krimmel SR, Scheidter KM, Monk J, Miller RL, Metoki A, Montez DF, Zheng A, Elbau I, Madison T, Nishino T, Myers MJ, Kaplan S, Badke D’Andrea C, Demeter DV, Feigelis M, Ramirez JSB, Xu T, Barch DM, Smyser CD, Rogers CE, Zimmermann J, Botteron KN, Pruett JR, Willie JT, Brunner P, Shimony JS, Kay BP, Marek S, Norris SA, Gratton C, Sylvester CM, Power JD, Liston C, Greene DJ, Roland JL, Petersen SE, Raichle ME, Laumann TO, Fair DA, Dosenbach NUF.

Journal: Nature. 2023 May;617(7960):351-359.

PMID: 37076628 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

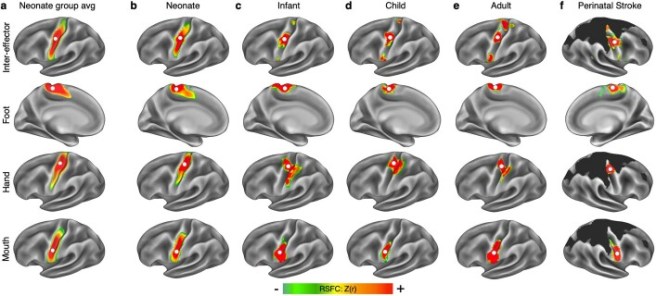

In this report, the investigators used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain to explore the topography of the motor cortex.

What is functional MRI?

fMRI is an imaging method that measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow.

How?

Our bodies use hemoglobin in red blood cells to deliver oxygen to neurons. When neuronal activity increases, there is a subsequent increase in demand for oxygen, which results in an increase in blood flow to regions of increased neural activity.

Hemoglobin has some interesting properties. For example, when oxygenated, it is diamagnetic (or repelled by a magnetic field), but when deoxygenated, it becomes paramagnetic (attracted by a magnetic field). These differences in magnetic properties allow for small differences in the MR signal to be detected, which means that levels of neural activity can be determined based on blood flow.

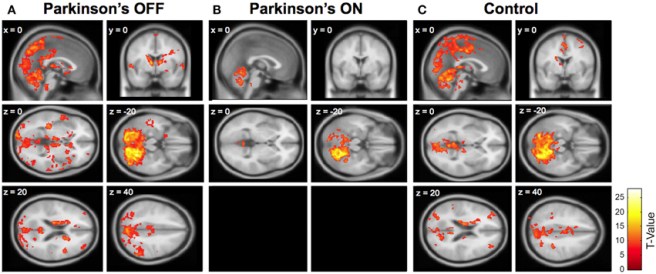

The image below demonstrates the kind of images that can be generated using fMRI (in this case showing altered cerebellar connectivity in Parkinson’s patients ON and OFF L-DOPA medication):

Source: Frontiers

Source: Frontiers

For those interested, this video further explains the science behind fMRI:

Ok. So what did the researchers find in their fMRI study?

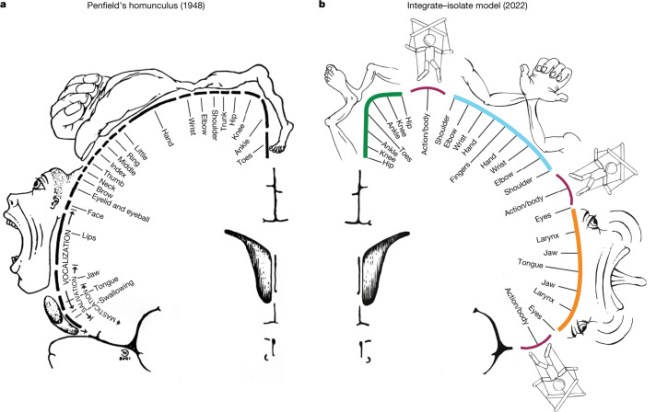

They found that “the classic homunculus is interrupted by regions with distinct connectivity, structure and function, alternating with effector-specific (foot, hand and mouth) areas“.

The researchers started their study by imaging the brains of 7 healthy adults in a resting state or performing some simple movements (such as closing a hand, flexing a foot, etc). These results found that the areas controlling the face, hands, and feet were generally located on the motor cortex where they expected them to be.

But between these dedicated areas were three thinner regions that did not seem to control any specific muscles or areas of the body. Instead, these areas appeared to be functionally linked to each other, but also to other regions of the brain that are involved in arousal, goal-oriented action, pain, and physiological control. So instead of the classical Penfield’s classical “homunculus” (on the left of the image below), the new map of the motor cortex appears to be more divided (on the right of the image below):

Source:PMC

Source:PMC

The researchers called these functionally linked areas the “somato-cognitive action network” (or SCAN). The SCAN regions in the image above are the ones on the right side of the image that have a puppet/marionette image above them.

Based on these results, the researchers concluded that the motor cortex involves two distinct and interactive systems:

- The well-known regions that provide precise movement control

- The SCAN system that helps coordinates complex movements.

Interesting. Has anyone ever looked at the SCAN in Parkinson’s?

Good question. And yes they have.

And this is where today’s post gets interesting!

Very recently researchers published this report:

Title: Parkinson’s disease as a somato-cognitive action network disorder.

Title: Parkinson’s disease as a somato-cognitive action network disorder.

Authors: Ren J, Zhang W, Dahmani L, Gordon EM, Li S, Zhou Y, Long Y, Huang J, Zhu Y, Guo N, Jiang C, Zhang F, Bai Y, Wei W, Wu Y, Bush A, Vissani M, Wei L, Oehrn CR, Morrison MA, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Hu Q, Yin Y, Cui W, Fu X, Zhang P, Wang W, Ji GJ, He J, Wang K, Fan D, Wang Z, Kimberley T, Little S, Starr PA, Richardson RM, Li L, Wang M, Wang D, Dosenbach NUF, Liu H.

Journal: Nature. 2026 Feb 4. Online ahead of print.

PMID: 41639440 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators collected fMRI brain imaging data from more than 860 individuals from research centers in the U.S. and China. Importantly, the dataset involved brain imaging results from people with Parkinson’s who had been treated with different types of therapies (including levodopa, deep brain stimulation, focused ultrasound, and transcranial stimulation).

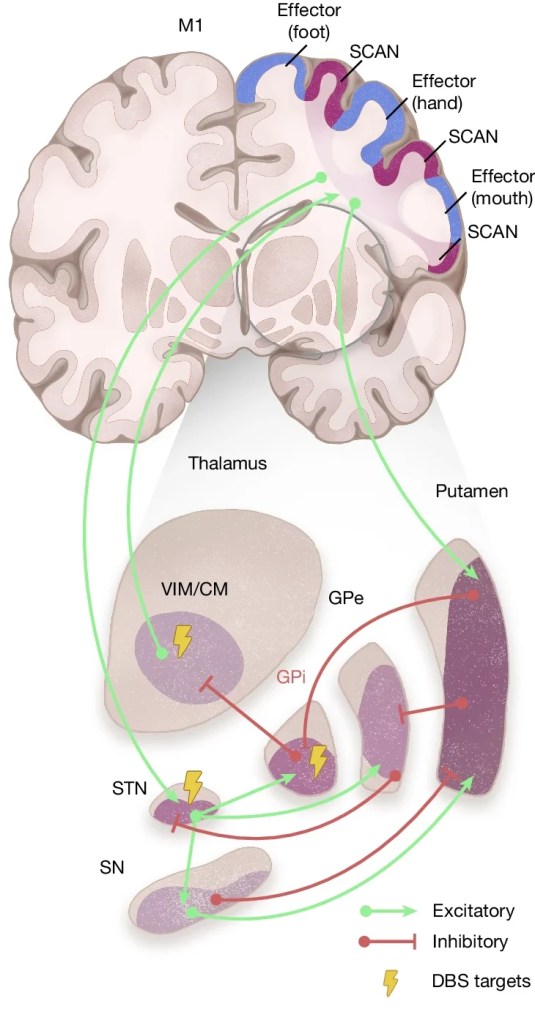

The researchers began their analysis by looking at the resting state of this network called SCAN, and comparing the Parkinson’s cases with unaffected control individuals. The first interesting finding that the scientists made was that many of the subcortical regions affected by Parkinson’s (and targeted with the various therapies) are strongly connected with the SCAN.

These subcortical regions are:

- The substantia nigra (SN) – where the dopamine neurons are lost

- The subthalamic nucleus (STN) – a target for deep brain stimulation

- The ventral intermediate nucleus/centromedian nucleus of the thalamus (VIM/CM) – a deep brain stimulation target

- The globus pallidus internus (GPi) – a deep brain stimulation target

- The globus pallidusexternus (GPe)

- The putamen – where dopamine is usually released

These areas and connecting pathways are displayed in the image below:

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

Interestingly, these areas were more strongly connected with the SCAN than with “effector-specific” (foot, hand, mouth) motor regions and other functional networks.

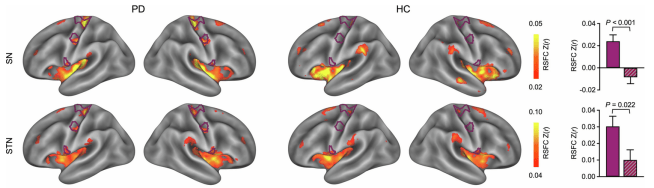

The second key finding that the researchers made in their resting state measures is that the resting-state functional connectivity between the SCAN and these subcortical structures was significantly elevated in individuals with Parkinsons (compared to the unaffected control cases). In the image below,, you can see that there is more red and yellow colouration in the motor cortex region of the Parkinson’s individual than the “healthy control” (HC) case when the investigators looked at connectivity between the substantia nigra (SN) and the subthalamic nucleus (STN):

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

Based on this finding, the researcher suggested that Parkinson’s could be characterised by hyperconnectivity of the SCAN.

What do you mean by hyperconnectivity?

By this the researchers meant that “the wiring” between this network and the subcortical regions mentioned above is overactive. Think of it as excessive communication within this SCAN network in people with Parkinson’s.

And importantly, the researchers emphasized that this hyperconnectivity (overactive communication) was specific to the SCAN and not to any other networks that they looked at. In addition, they also noted that the SCAN hyperconnectivity was missing in three other neurological conditions that they used as positive control conditions (those conditions were essential tremor, dystonia and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). This observation led the researchers to ask if SCAN hyperconnectivity could potentially serve as a non-invasive biomarker for Parkinson’s?

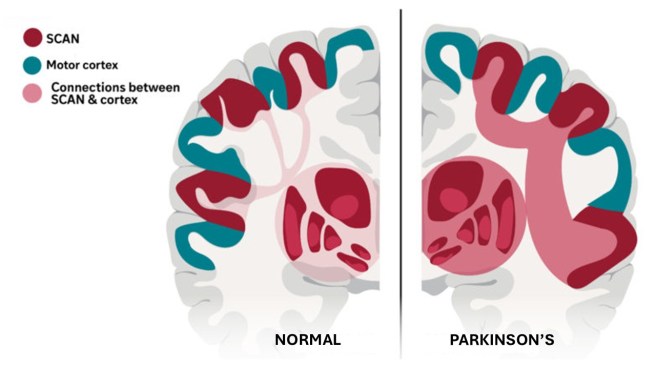

Completing this part of their study, the researchers concluded that SCAN hyperconnectivity was a feature of Parkinson’s. If you made a top-down slice through the motor cortex of a person without Parkinson’s and compared it with the same from a person with Parkinson, it would look something like this:

Source: Adapted from WashU

Source: Adapted from WashU

Interesting. Did the SCAN hyperconnectivity match severity of Parkinson’s symptoms?

Great question, And yes. The researchers looked at this and they found significant associations between resting-state functional connectivity between the SCAN + the subcortical structures and motor symptoms, cognition, anxiety, and depression.

The higher the hyperconnectivity, the worse the symptoms.

Does treatment help with this SCAN hyperconnectivity?

So this is the third interesting finding of this report.

The researchers found that dopaminergic therapy (levodopa), focused ultrasound, and neuromodulation (deep brain stimulation or transcranial stimulation) all reduced hyperconnectivity of the SCAN, helping to alleviate Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

Interesting. How can this new data be used to help with Parkinson’s?

Another great question. And the researchers who published this report are way ahead of us here.

Using their findings, the investigators developed a new “precision treatment system” that is capable of targeting the SCAN. It is a non-invasive, transcranial stimulation approach “with millimeter accuracy“.

To test this new treatment approach, the researchers conducted a clinical trial in which 18 Parkinson’s patients received the SCAN-targeted transcranial stimulation for two weeks and they were compared with 18 Parkinson’s patients who received stimulation to another brain region (this was the control group). The SCAN targeting treatment involved four 10-minute stimulation sessions per day with 50-minute intervals in between over the two weeks of the study (Click here to read more about the design of the study).

The SCAN targeted group showed a 56% response rate after two weeks, compared to just a 22% response rate in the control group. Response rate was measured using the standard clinical rating scale (the MDS-UPDRS-III).

Videos of the pre and post treatment performance has been posted on social media (Twitter) – click here, here and here if you would like to view these films.

So what happens next?

This SCAN in Parkinson’s research was conducted by a multi-national group of researchers from China and the USA. Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis were the first to describe SCAN and they collaborated Chinese researchers to explore Parkinson’s.

The researchers from Washington University have foundered a biotech company called Turing Medical which is seeking to conduct further clinical trials using this new treatment approach “to treat gait dysfunction in Parkinson’s patients” (Source).

In addition, the Chinese researchers have a tech company called Galaxy Brain Scientific, which developed the proprietary personalized Brain Functional Sectors technology that was used in the pilot clinical study mentioned in the SCAN in Parkinson’s report.

Galaxy Brain Scientific “is already moving to bring these insights to the clinical frontline, having begun a pivotal registration trial for Class III devices dedicated to treating Parkinson’s” (Source). So there should be a lot of activity focused on the SCAN over the next year.

Galaxy Brain Scientific “is already moving to bring these insights to the clinical frontline, having begun a pivotal registration trial for Class III devices dedicated to treating Parkinson’s” (Source). So there should be a lot of activity focused on the SCAN over the next year.

We will keep an eye out for any new developments and let you know here on the SoPD website.

What does the Parkinson’s research community think of these new results?

This new report has generated a lot of interest within the Parkinson’s research community.

The Science Media Centre in Spain has a nice page on their website where they have asked Parkinson’s experts to give their initial thoughts on the new research (Click here to read them all). Here are are a few quotes that stood out:

- “This study presents an ambitious analysis based on a large amount of neuroimaging data and different therapeutic approaches to Parkinson’s“

- “Its main contribution, however, is not methodological but conceptual: it proposes that Parkinson’s disease, which was already known to produce motor and non-motor symptoms, involves the alteration of a broader brain network“

- “It is important, however, to avoid exaggerated interpretations“

- “The experiment with transcranial magnetic stimulation, which provides the most direct causal and therapeutic evidence, is limited in size and presents possible technical confounding factors“

- “Studies using other techniques will be necessary to confirm or refute the proposed hypothesis, as well as larger, independent trials with more rigorous designs before these ideas can be transferred to routine clinical practice”

- “It is important to be cautious: at this point, it does not imply a cure or an immediate change in clinical practice“

- “The techniques for measuring SCAN-subcortical structure connectivity are difficult to set up in a normal healthcare centre, and I therefore do not believe that this article will change daily clinical practice in the short term“

Oooh, the Parkinson’s research community are a sober bunch. But I agree with the need for cautious interpretation.

Obviously, the first thing we need is to see independent replication of this study in a fresh cohort of people with Parkinson’s. Before we can start to get too excited, we have to determine if – all things being the same – other researchers find the same results. We have been to this rodeo before with novel pharmacological therapies or vibrating gloves, and after a lot of initial excitement surrounding awe-inspiring results, the hard reality of science and biology has brough us back down to Earth. So I am going to temper my enthusiasm until we see replication.

So what does it all mean?

New research highlights the hyperconnectivity of a specific network in the brain called SCAN as being central to the Parkinson’s, suggesting a much broader network dysfunction than previously believed is involved with the condition. The research reinforces the idea that Parkinson’s is not just a “movement disorder”, and that it also impacts a broader neural circuitry that involves the coordination of action, motivation, and other bodily functions.

Good research always raises lots of questions and point towards future avenues of investigation. This new research on the SCAN network in people with Parkinson’s causes one to ask lots of questions. For example:

- Could SCAN hyperconnectivity be used as a biomarker for Parkinson’s? (challenging as brain imaging is required)

- Could SCAN hyperconnectivity be used as a measure of disease progression in clinical trials (perhaps on a group level, but I suspect that we are not there yet on the individual level)

- Could SCAN hyperconnectivity be used for differential diagnosis? (it is interesting that essential tremor and dystonia do not involve SCAN hyperconnectivity, but I would be curious to know if other Parkinsonisms (like Lewy body dementia or Multiple Systems Atrophy) are also charcterised by this feature)

- Does long-term modulation of SCAN actually slow Parkinson’s progression? (Could intervention this have a disease modifying effect? Which begs the next question)

- Which comes first: SCAN dysfunction or loss of dopamine neurons? (How does this SCAN dysfunction develop? Is it causal, or just the result of other things going wrong)

- What does the SCAN in people with “prodromal” Parkinson’s look like? (Could modulation of the SCAN help people at risk of developing Parkinson’s? Could it potentially slow down the progression to diagnosis?)

- How could this new research be used to improve adaptive deep brain stimulation? (Rather than building something completely new, could a combination of therapeutic approaches be explored to move things forward more rapidly?)

I have to admit that I like the potentially paradigm shifting nature of this research. And I think others are also intrigued by it. Given that targeted modulation of the SCAN normalised the connectivity better than traditional dopamine medication, perhaps (as Ben Stecher has suggested on his website) we should focus our attention on modulating these circuits “rather than just flooding the brain with chemicals“. And as Ben wrote “By identifying the specific nodes of the SCAN in each patient, we can go beyond the “one-size-fits-all” model that has stalled progress for decades“.

Interesting times. Stay tuned for more on this.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR S NOTE: The author of this post is an employee of Cure Parkinson s, so he might be a little bit biased in his views on research and clinical trials supported by the trust. That said, the trust has not requested the production of this post, and the author is sharing it simply because it may be of interest to the Parkinson s community.

The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken based on what has been read on the website are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Nature.