In her excellent book – ‘The Enlightened Mr. Parkinson: The Pioneering Life of a Forgotten English Surgeon’ (Icon Books Ltd) – Dr Cherry Lewis wrote that the earliest reference to Mr James Parkinson’s ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy’ was an advert placed in the Morning Chronicle of Saturday 31st May (1817), under a list of books “published this day”.

Given this information, we searched the Britishnewspaperarchive online and captured the image presented above.

Today is the 200th anniversary of the publication of ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy’.

In this post, we continue our four part series on the man behind the disease by discussing the ‘Essay’ on the 200th anniversary of its publication.

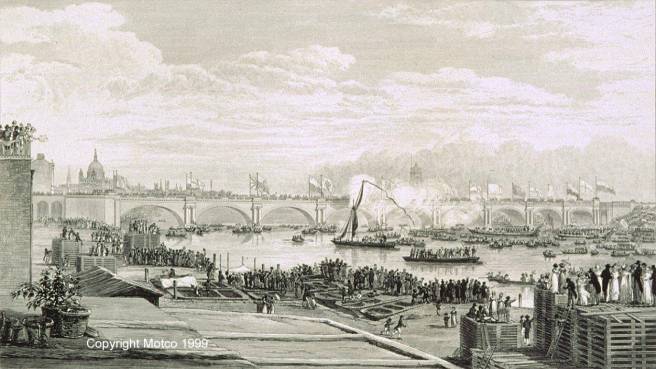

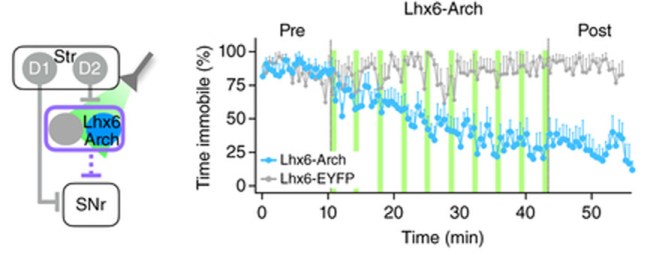

The opening of Waterloo Bridge on the 18th of June 1817. Source: Thames

A few weeks before the opening of the Waterloo Bridge, James Parkinson published the booklet that would go on to immortalise him in the annals of medicine. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy, which spans 66 pages, was published by Sherwood, Neely and Jones of London, and printed by Whittingham and Rowland in 1817.

At the date of printing it sold for 3 shillings (approx. £9 or US$12).

Much has been written about the essay, and we here at the SoPD feel that we have little to actually add to the conversation. Thus our post today will simply provide an overview of the book (a highlights package, if you will), summarising it for those who do not have time to read its entirety (a full copy of the essay can be found by clicking here).

Source: Project Gutenberg

The Essay begins with a preface and is then divided into five chapters, labeled:

1. “DEFINITION—HISTORY—ILLUSTRATIVE CASES”

2. “PATHOGNOMONIC SYMPTOMS EXAMINED—TREMOR COACTUS—SCELOTYRBE FESTINANS”

3. “SHAKING PALSY DISTINGUISHED FROM OTHER DISEASES FROM WHICH IT MAY BE CONFOUNDED”

4. “PROXIMATE CAUSE—REMOTE CAUSES—ILLUSTRATIVE CASES”

5. “CONSIDERATIONS RESPECTING THE MEANS OF CURE”

The preface

In the preface of the book, James gave his reasons for actually writing it. Basically, he wanted to make others aware of what he considered a previously un-described condition.

At the heart of the preface is a paragraph, which reads:

“The disease is of long duration: to connect, therefore, the symptoms which occur in its later stages with those which mark its commencement, requires a continuance of observation of the same case, or at least a correct history of its symptoms, even for several years. Of both these advantages the writer has had the opportunities of availing himself; and has hence been led particularly to observe several other cases in which the disease existed in different stages of its progress. By these repeated observations, he hoped that he had been led to a probable conjecture as to the nature of the malady, and that analogy had suggested such means as might be productive of relief, and perhaps even of cure, if employed before the disease had been too long established. He therefore considered it to be a duty to submit his opinions to the examination of others, even in their present state of immaturity and imperfection.”

At the end of the preface, James hopes that “friends to humanity and medical science…might be excited to extend their researches to this malady”. And in that situation James would “think himself fully rewarded by having excited the attention of those, who may point out the most appropriate means of relieving a tedious and most distressing malady”.

Chapter 1

In the first chapter, James begins with a description of the Shaking Palsy (or ‘Paralysis agitans’ as he called it), that resembles modern Parkinson’s disease almost perfectly:

“Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, in parts not in action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk forwards, and to pass from a walking to a running pace: the senses and intellects being uninjured.”

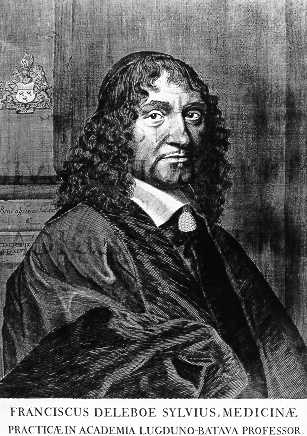

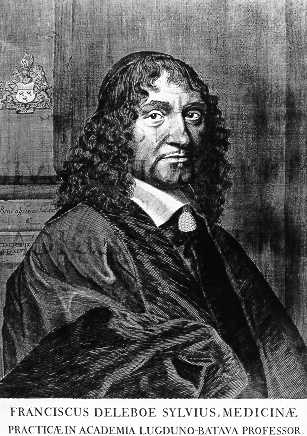

He then moves on to provide a breakdown of the features that make up this condition, which includes a history of tremor that takes into account the works of Aelius “Galen” Galenus, Sylvius de la Boë, and Johann Juncker.

James starts by noting the slow progress of the condition:

“So slight and nearly imperceptible are the first inroads of this malady, and so extremely slow is its progress, that it rarely happens, that the patient can form any recollection of the precise period of its commencement. The first symptoms perceived are, a slight sense of weakness, with a proneness to trembling in some particular part; sometimes in the head, but most commonly in one of the hands and arms.”

How familiar does this sound?

And please remember, James was describing this condition for the first time based only on his own observations of just six individuals (three from a distance). His attention to detail was amazing, taking into account so many different aspects of the condition (from the obvious motor features to issues with bowel movements). And he noted it all down in the essay.

He continues by describing the progress of the condition over time:

“But as the malady proceeds,….The propensity to lean forward becomes invincible, and the patient is thereby forced to step on the toes and fore part of the feet, whilst the upper part of the body is thrown so far forward as to render it difficult to avoid falling on the face.”

His description took into account the entire history of the condition, starting from the appearance of the first features and finishing with the late stages of the disease:

“As the disease proceeds towards its last stage, the trunk is almost permanently bowed, the muscular power is more decidedly diminished, and the tremulous agitation becomes violent….As the debility increases and the influence of the will over the muscles fades away, the tremulous agitation becomes more vehement. It now seldom leaves him for a moment;”

After describing the basic clinical appearance of the condition, James then immediately moves on to each of the six cases he based his description on.

Case I was the first encounter of this condition for James. It was also probably one of the case that James was most familiar with as he wrote “every circumstance occurred which has been mentioned in the preceding history”. In his writing of Case I, however, James was rather brief:

Case I

“The subject of this case was a man rather more than fifty years of age, who had industriously followed the business of a gardener, leading a life of remarkable temperance and sobriety. The commencement of the malady was first manifested by a slight trembling of the left hand and arm, a circumstance which he was disposed to attribute to his having been engaged for several days in a kind of employment requiring considerable exertion of that limb. Although repeatedly questioned, he could recollect no other circumstance which he could consider as having been likely to have occasioned his malady.”

The “next case” (as James wrote it, indicating that the cases are presented in chronological order), Case II, was a man that James casually met with in the street.

Case II

“It was a man sixty-two years of age; the greater part of whose life had been spent as an attendant at a magistrate’s office. He had suffered from the disease about eight or ten years. All the extremities were considerably agitated, the speech was very much interrupted, and the body much bowed and shaken. He walked almost entirely on the fore part of his feet, and would have fallen every step if he had not been supported by his stick. He described the disease as having come on very gradually,…”

Case II attributed his condition to his choice of lifestyle (“irregularities in mode of living and indulgence in spiritous liquors,”), which James did not give any credit. This was probably because much of the rest of the city partook in such a lifestyle without the emergence of the disease. Ever the humanitarian, though, James points towards the unfortunate situation that these individuals found themselves:

“He was the inmate of a poor-house of a distant parish, and being fully assured of the incurable nature of his complaint, declined making any attempts for relief.”

The third case was also “noticed casually in the street“. James did interact with the man though, determining that he had been a sailor who attributed his condition to having been for many months in a Spanish prison:

Case III.

“The subject…was a man of about sixty-five years of age, of a remarkable athletic frame. The agitation of the limbs, and indeed of the head and of the whole body, was too vehement to allow it to be designated as trembling. He was entirely unable to walk; the body being so bowed, and the head thrown so forward, as to oblige him to go on a continued run, and to employ his stick every five or six steps to force him more into an upright posture, by projecting the point of it with great force against the pavement.”

The 4th case was a gentleman (of about fifty-five years of age) who presented himself to James. He claimed that he had first experienced the trembling of the arms about five years before. In this case, we see the nature of the medical treatments during that period (that being a preference for blood letting):

Case IV.

“His application was on account of a considerable degree of inflammation over the lower ribs on the left side, which terminated in the formation of matter beneath the fascia. About a pint was removed on making the necessary opening; and a considerable quantity discharged daily for two or three weeks. On his recovery from this, no change appeared to have taken place in his original complaint; and the opportunity of learning its future progress was lost by his removal to a distant part of the country”

Case V was the subject that James had the least amount of information about and observed the gentleman only from a distance (it is curious to note that all of these cases were males – who have a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease – click here for more on this):

Case V.

“…one of the characteristic symptoms of this malady, the inability for motion, except in a running pace, appeared to exist in an extraordinary degree. It seemed to be necessary that the gentleman should be supported by his attendant, standing before him with a hand placed on each shoulder, until, by gently swaying backward and forward, he had placed himself in equipoise; when, giving the word, he would start in a running pace, the attendant sliding from before him and running forward, being ready to receive him and prevent his falling, after his having run about twenty paces”

Case VI may have been the individual that spurred James to write his essay as it was one “which presented itself to observation since those above-mentioned,”. Thus, James had the benefit of hindsight and all the information that he had gained from the previous cases, when he was confronted with Case VI and he could make a thorough study of the individual. In case VI, James also hints at the indiscriminate nature of the condition, afflicting people from all sorts of backgrounds.

Case VI.

“The gentleman who was the subject of it is seventy-two years of age. He has led a life of temperance, and has never been exposed to any particular situation or circumstance which he can conceive likely to have occasioned, or disposed to this complaint; which he rather seems to regard as incidental upon his advanced age, than as an object of medical attention….About eleven or twelve, or perhaps more, years ago, he first perceived weakness in the left hand and arm, and soon after found the trembling commence. In about three years afterwards the right arm became affected in a similar manner: and soon afterwards the convulsive motions affected the whole body, and began to interrupt the speech…Of late years the action of the bowels had been very much retarded;…”

James notes with Case VI that the gentleman had the capacity to temporarily control his situation by his own will:

“…he, being then just come in from a walk, with every limb shaking, threw himself rather violently into a chair, and said, ‘Now I am as well as ever I was in my life.’ The shaking completely stopped; but returned within two minutes”

At the end of the section on CaseVI, James notes some input from the wife of the gentleman:

“…if whilst walking he felt much apprehension from the difficulty of raising his feet, if he saw a rising pebble in his path? he avowed, in a strong manner, his alarm on such occasions; and it was observed by his wife, that she believed, that in walking across the room, he would consider as a difficulty the having to step over a pin”

Having finished reading Chapter 1, it is truly remarkable to recall that James was describing what he thought was a previously unrecognised condition. Remarkable because of the depth and scope he provides. It is difficult to put oneself in his shoes, given that we are now so familiar with the disease. But it does Mr Parkinson great credit both as a surgeon and a writer that what he is describing feels so familiar.

Chapter 2

Here James returns to the cardinal features of the condition as he sees them, starting with the tremor:

1. Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened voluntary muscular power, in parts, not in action, and even supported.

In this first section, James breaks down the different types of tremor in an effort to better understand this condition he is describing.

“It is necessary that the peculiar nature of this tremulous motion should be ascertained, as well for the sake of giving to it its proper designation, as for assisting in forming probable conjectures, as to the nature of the malady, which it helps to characterise”

And again, James cites the works of Galen and Sylvius de la Boë.

Galen. Source: thefamouspeople

“The separation of palpitation of the limbs (Palmos of Galen, Tremor Coactus of de la Boë) from tremor, is the more necessary to be insisted on, since the distinction may assist in leading to a knowledge of the seat of the disease.”

de la Boë. Source: Wikipedia

James concludes that the tremor associated with his new condition is distinct given that the tremor is nearly constant or “induced immediately on bringing the parts into action”

The second characteristic feature of this newly described condition, according to James, is the gait and posture:

2. A propensity to bend the trunk forwards, and to pass from a walking to a running pace.

Here James discusses the works of François Boissier de Sauvages de Lacroix (1706 – 1767), a French physician and botanist who is credited with establishing a methodical nosology for diseases (a classification system).

de Sauvage. Source: Homeoint

“Mons. de Sauvages attributes this complaint to a want of flexibility in the muscular fibres. Hence, he supposes, that the patients make shorter steps, and strive with a more than common exertion or impetus to overcome the resistance; walking with a quick and hastened step, as if hurried along against their will”

It is a demonstration of Mr Parkinson’s studious nature and high general level of intelligence that he was so familiar with the works of de Sauvage – it is a simple task for us modern folk to simply ‘google’ anything we don’t know or are curious about. Where did James go to find his background research for his Esssay?

Having clearly outlined the features of the condition, James next moves to Chapter 3 where he attempts to differentiate this condition from other maladies.

Chapter 3

James did not want to have this new condition he was describing confused with other diseases, hence the meticulous description of the symptoms/features.

“…it is necessary to show that it is a disease which does not accord with any which are marked in the systematic arrangements of nosologists; and that the name by which it is here distinguished has been hitherto vaguely applied to diseases very different from each other, as well as from that to which it is now appropriated”

James’ choice of name for the new condition was ‘Shaking palsy’, but he noted that this label had been used several times before. For example, one Dr. Charlton had used the label in describing a particular case:

“Another case, which the Doctor designates as ‘A Shaking Palsy,’ apparently from worms, he describes thus, “A poor boy, about twelve or thirteen years of age, was seized with a Shaking Palsy. His legs became useless, and together with his head and hands, were in continual agitation; after many weeks trial of various remedies, my assistance was desired…His bowels being cleared, I ordered him a grain of Opium a day in the gum pill; and in three or four days the shaking had nearly left him.” By pursuing this plan, the medicine proving a vermifuge, he could soon walk, and was restored to perfect health”

Given the level of detail that James goes into in other chapters, it is fair to say that chapter 3 is light reading. But it finishes strong as James describes the truly distinguishing feature of his version of Shaking palsy – that being the resting state nature of the tremor:

“If the trembling limb be supported, and none of its muscles be called into action, the trembling will cease. In the real Shaking Palsy the reverse of this takes place, the agitation continues in full force whilst the limb is at rest and unemployed;”

And it was this feature for James that could be used to distinguish it from other conditions.

Chapter 4

In Chapter 4, James tries to understand the cause of the condition, but right up front he acknowledges that this is a rather difficult task:

“Unaided by previous inquiries immediately directed to this disease, and not having had the advantage, in a single case, of that light which anatomical examination yields, opinions and not facts can only be offered”

In addition, James notes that “Cases illustrative of the nature and cause of this malady are very rare”

He does an admirable job in his endeavour here, however, by looking at previously reported cases of other diseases that share some similarities with this new condition. And James actually describes cases that he himself has dealt with (albeit by informally), but he takes pains to point out that these cases are different to the new conditions that he is describing in this essay. For example:

“…the unhappy subject of this malady was casually met in the street, shifting himself along, seated in a chair; the convulsive motions having ceased, and the limbs having become totally inert, and insensible to any impulse of the will”

In this case, the man had been treated with mercury for a venereal infection (click here to read more about early mercury treatments) many years before, which had left him with convulsive movements restricted to the legs.

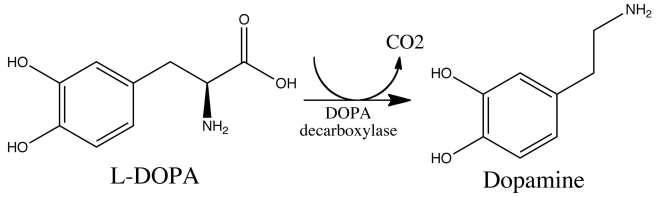

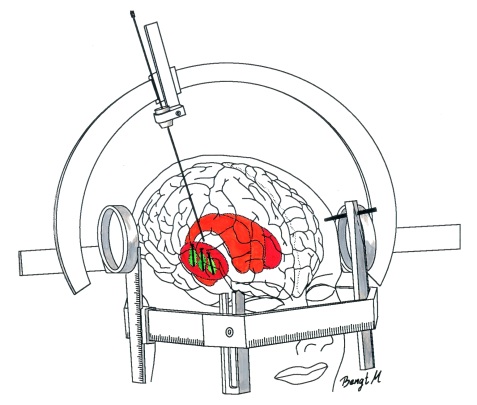

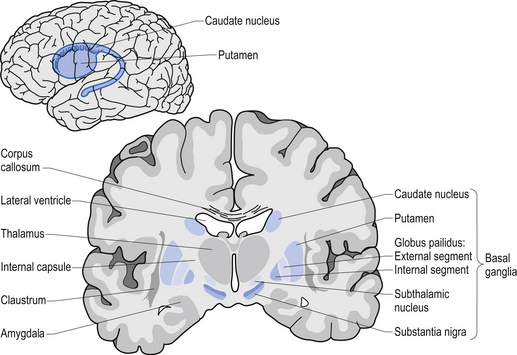

Using this case study approach, however, James proposes that the disease is targeting or affecting an area of the brain stem called the medulla oblongata (which is affected in Parkinson’s disease, and is actually not too far from the midbrain where the significant loss of the dopamine neurons gives rise to the motor features of Parkinson’s disease).

Location of the midbrain and medulla in the human brain. Source: Wikipedia

Chapter 5

In chapter 5, James expresses hope that a successful treatment is almost at hand:

“…there appears to be sufficient reason for hoping that some remedial process may ere long be discovered, by which, at least, the progress of the disease may be stopped”

Exactly 200 years on, I think it is fair to say that James was a bit too optimistic in nature, but we are certainly a lot closer now to stopping the disease than he was then.

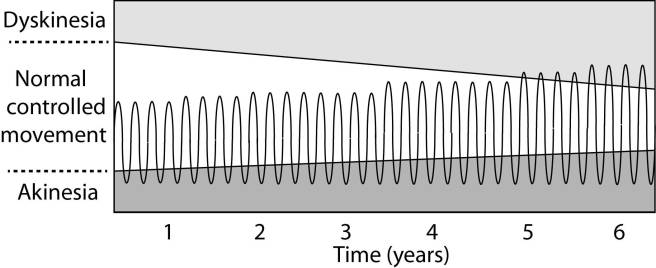

James was instructive in how he thought it was best to attack the condition. He divides the condition into two halves, early and late, based on the spread of the motor features from individual limbs to other areas of the body. And he is rather certain that early diagnosis was essential if there was to be any chance of cure.

He also thought that the condition simply required some reverse engineering:

“…it seems as if we were able to trace the order and mode in which the morbid changes may proceed in this disease”

But his thoughts on how to treat the disease were largely based on the medical practises of the time (as they are today):

“…blood should be first taken from the upper part of the neck,…After which vesicatories should be applied to the same part, and a purulent discharge obtained by appropriate use of the Sabine Liniment; having recourse to the application of a fresh blister, when from the diminution of the discharging surface, pus is not secreted in a sufficient quantity”

He provides further thoughts on this treatment, but then offers the caveat that this is merely an opinion:

“Until we are better informed respecting the nature of this disease, the employment of internal medicines is scarcely warrantable;”

James also then comments on the insidious nature and the slow progress of the disease, as it:

“Seldom occurring before the age of fifty, and frequently yielding but little inconvenience for several months, it is generally considered as the irremediable diminution of the nervous influence, naturally resulting from declining life; and remedies therefore are seldom sought for”

And this leaves the sufferer focusing on:

“The weakened powers of the muscles in the affected parts is so prominent a symptom, as to be very liable to mislead the inattentive, who may regard the disease as a mere consequence of constitutional debility. If this notion be pursued, and tonic medicines, and highly nutritious diet be directed, no benefit is likely to be thus obtained; since the disease depends not on general weakness, but merely on the interruption of the flow of the nervous influence to the affected parts”

This is very insightful of James. He understood that it was not the weakness felt in the muscles that was paramount in this condition, but rather a dysfunction in the brain.

He concludes the essay with the following:

“To such researches the healing art is already much indebted for the enlargement of its powers of lessening the evils of suffering humanity. Little is the public aware of the obligations it owes to those who, led by professional ardour, and the dictates of duty, have devoted themselves to these pursuits, under circumstances most unpleasant and forbidding. Every person of consideration and feeling, may judge of the advantages yielded by the philanthropic exertions of a Howard; but how few can estimate the benefits bestowed on mankind, by the labours of a Morgagni, Hunter, or Baillie.

FINIS.”

Regarding the last line, I may be displaying my ignorance here with regards to ‘a Howard’, but I suspect James is referring to John Howard (1726 – 1790), an English philanthropist of James’ era:

John Howard. Source: Wikipedia

Although, “a Howard” is also an old slang term used to describe a man (any man) of great character!

Giovanni Battista Morgagni. Source: Wikipedia

Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682 – 1771) was an Italian anatomist, who is generally regarded as the father of modern anatomical pathology.

John Hunter. Source: Wikipedia

John Hunter (1728 – 1793) was a Scottish surgeon – one of the most distinguished scientists/surgeons of his day. He was an early advocate of careful observation and scientific method in medicine, and James personally learned a great deal from him. Between October 1785 and April 1786, James attended the evening lectures provided by Hunter. James wrote down the lectures verbatim (in shorthand) and his notes were later published by his son John (“Hunterian Reminiscences, Being The Substance Of A Course Of Lectures On The Principles And Practice Of Surgery Delivered By John Hunter In The Year 1785″ – a precious resource given that Hunter’s own notes were later destroyed by fire).

Matthew Baillie. Source: Wikipedia

Matthew Baillie was another Scottish physician and pathologist. A pupil of his uncle, John Hunter (above), Ballie provided us with the first systematic study of pathology. James was certainly familiar with Ballie, as he cited his works.

For further reading on An Essay on the Shaking Palsy we recommend a review written by Prof Brian Hurwitz (King’s College London) called Urban Observation and Sentiment in James Parkinson’s Essay on the Shaking Palsy (1817) which provides fantastic insight into James, the age he lived in, the essay itself, and the reception of the essay (Click here to read that review).

This post was written in observation of the 200 year anniversary of the publishing of the Essay on the Shaking Palsy. It is part two in a four part series on the life of Mr James Parkinson (click here for part one). In the third instalment, we will look at his life’s work, before the fourth part looks at his final years and his legacy.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from the Britishnewspaperarchive