For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the Journey with Parkinson’s blog to bring readers an ‘Introduction to the historical timeline on Parkinson’s disease’.

For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the Journey with Parkinson’s blog to bring readers an ‘Introduction to the historical timeline on Parkinson’s disease’.

The idea for this project started as a conversation between Frank and his partner Barbara during a recent weekend at the beach in North Carolina.

Frank said: “Wouldn’t it be cool to publish a Parkinson’s historical timeline for Parkinson’s awareness month?”

However, to complete this project Frank felt it necessary to bring in some extra help in the form of a Parkinson’s expert.

And when everyone else said they were too busy, Frank contacted us.

Truly flattered, we immediately said yes. And the rest is history.

We are happy to present the milestones in Parkinson’s disease research and discover, though we do apologise to the clinicians, scientists, health-care specialists, and their projects that were not cited here but we limited the timeline to ~50 notations.

Below there are six panels outlining different stages of the history of Parkinson’s disease, and under each of them we have briefly described each of the events in the panel.

We hope you like it.

1817-1919- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 1a: Historical):

First description of Parkinson’s disease

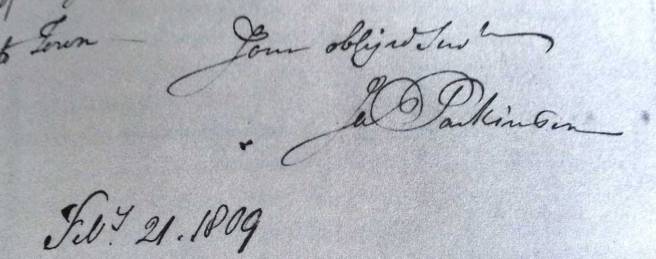

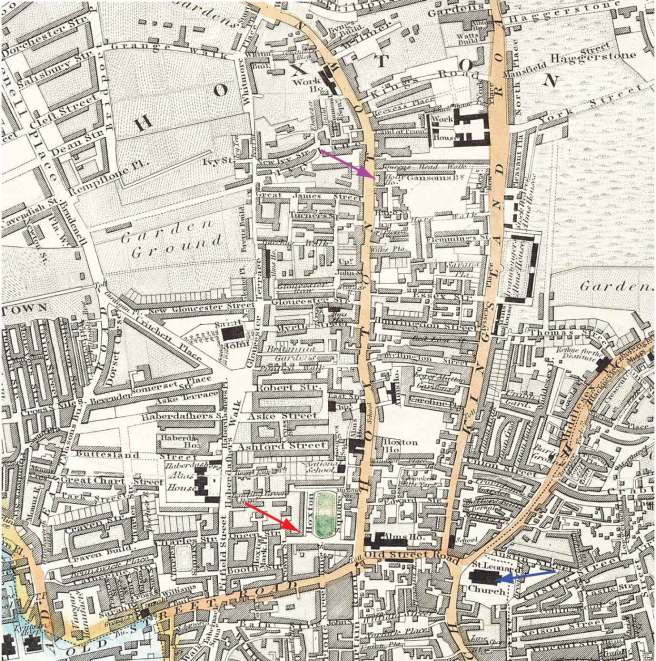

In 1811, Mr James Parkinson of no. 1 Hoxton Square (London) published a 66 page booklet called an ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy’. At the date of printing, it sold for 3 shillings (approx. £9 or US$12). The booklet was the first complete description of a condition that James called ‘Paralysis agitans’ or shaking palsy. In his booklet, he discusses the history of tremor and distinguishes this new condition from other diseases. He then describes three of his own patients and three people who he saw in the street.

The naming of Parkinson’s disease

Widely considered the ‘Father of modern neurology’, the importance of Jean-Martin Charcot’s contribution to modern medicine is rarely in doubt. From Sigmund Freud to William James (one of the founding fathers of Psychology), Charcot taught many of the great names in the early field of neurology. Between 1868 and 1881, Charcot focused much of his attention on the ‘paralysis agitans’. Charcot rejected the label ‘Paralysis agitans’, however, suggesting that it was misleading in that patients were not markedly weak and do not necessarily have tremor. Rather than Paralysis Agitans, Charcot suggested that Maladie de Parkinson (or Parkinson’s disease) would be a more appropriate name, bestowing credit to the man who first described the condition. And thus 70 years after passing away, James Parkinson was immortalized with the disease named after him.

The further clinical characterisation of Parkinson’s disease

British neurologist Sir William Gowers published a two-volume text called the Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System (1886, 1888). In this book he described his personal experience with 80 people with Parkinson’s disease in the 1880s. He also identified the subtle male predominance of the disorder and provided illustrations of the characteristic posture. In his treatment of Parkinson’s tremor, Gower used hyoscyamine, hemlock, and hemp (cannabis) as effective agents for temporary tremor abatement.

The discovery of the chemical dopamine

In the Parkinsonian brain there is a severe reduction in the chemical dopamine. This chemical was first synthesised in 1910 by George Barger and James Ewens at the Wellcome labs in London, England.

The discovery of Lewy bodies

One of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease in the brain is the presence of Lewy bodies – circular clusters of protein. In 1912, German neurologist Friedrich Lewy, just two years out of medical school and still in his first year as Director of the Neuropsychiatric Laboratory at the University of Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland) Medical School discovered these ‘spherical inclusions’ in the brains of a people who had died with Parkinson’s disease.

The importance of the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease

The first brain structure to be associated with Parkinson’s disease was the substantia nigra. This region lies in an area called the midbrain and contains the majority of the dopamine neurons in the human brain. It was in 1919 that a Russian graduate student working in Paris, named Konstantin Tretiakoff, first demonstrated that the substantia nigra was associated with Parkinson’s disease. Tretiakoff also noticed circular clusters in the brains he examined and named them ‘corps de Lewy’ (or Lewy bodies) after the German neurologist Friedrich Lewy who first discovered them.

1953-1968- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 1b: Historical):

The first complete pathologic analysis of the Parkinsonian brain

The most complete pathologic analysis of Parkinson’s disease with a description of the main sites of damage was performed in 1953 by Joseph Godwin Greenfield and Frances Bosanquet.

The discovery of a functional role for dopamine in the brain

Until the late 1950s, the chemical dopamine was widely considered an intermediate in the production of another chemical called norepinephrine. That is to say, it had no function and was simply an ingredient in the recipe for norepinephrine. Then in 1958, Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson discovered that dopamine acts as a neurotransmitter – a discovery that won Carlsson the 2000 Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine.

The founding of the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation

In 1957, a nonprofit organisation called the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation was founded by William Black. It was committed to finding a cure for Parkinson’s Disease. Since its founding in 1957, PDF has funded more than $115 million worth of scientific research in Parkinson’s disease.

The discovery of the loss of dopamine in the brain of people with Parkinson’s disease

In 1960, Herbert Ehringer and Oleh Hornykiewicz demonstrated that the chemical dopamine was severely reduced in brains of people who had died with Parkinson’s disease.

The first clinical trials of Levodopa

Knowing that dopamine can not enter the brain and armed with the knowledge that the chemical L-dopa was the natural ingredient in the production of dopamine, Oleh Hornykiewicz & Walther Birkmayer began injecting people with Parkinson’s disease with L-dopa in 1961. The short term response to the drug was dramatic: “Bed-ridden patients who were unable to sit up, patients who could not stand up when seated, and patients who when standing could not start walking performed all these activities with ease after L-dopa. They walked around with normal associated movements and they could even run and jump.” (Birkmayer and Hornykiewicz 1961).

The first internationally-used rating system for Parkinson’s disease

In 1967, Melvin Yahr and Margaret Hoehn published a rating system for Parkinson’s disease in the journal Neurology. It involves 5 stages, ranging from unilateral symptoms but no functional disability (stage 1) to confinement to wheel chair (stage 5). Since then, a modified Hoehn and Yahr scale has been proposed with the addition of stages 1.5 and 2.5 in order to help better describe the intermediate periods of the disease.

Perfecting the use of L-dopa as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease

In 1968, Greek-American scientist George Cotzias reported dramatic effects on people with Parkinson’s disease using oral L-dopa. The results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. and L-dopa becomes a therapeutic reality with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approving the drug for use in Parkinson’s disease in 1970. Cotzias and his colleagues were also the first to describe L-dopa–induced dyskinesias.

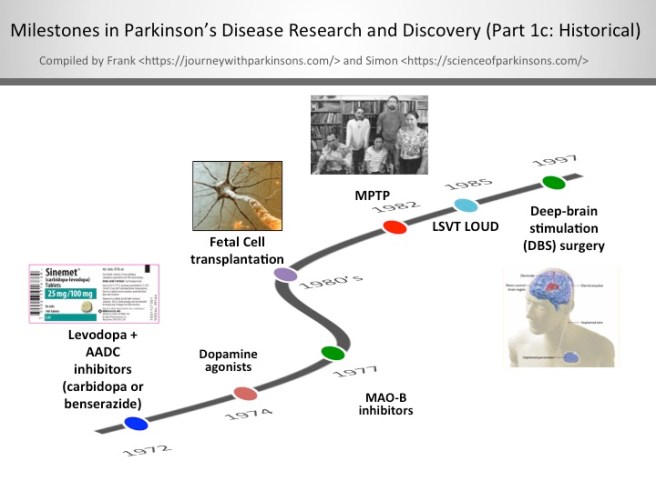

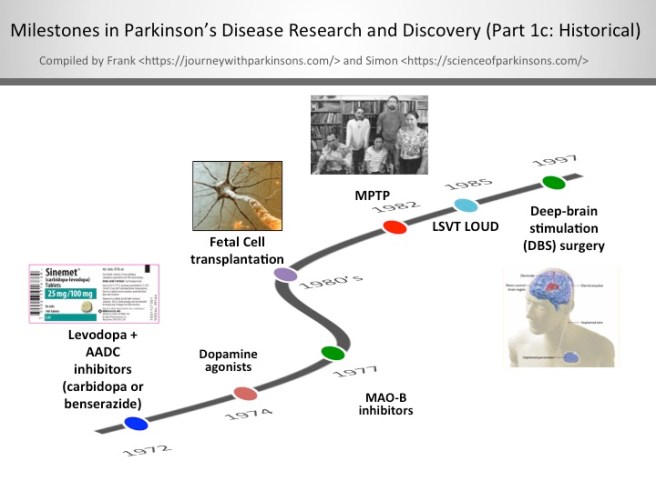

1972-1997- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 1c: Historical):

Levodopa + AADC inhibitors (carbidopa or benserazide)

When given alone levodopa is broken down to dopamine in the bloodstream, which leads to some detrimental side effects. By including an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) inhibitor with levodopa allows the levodopa to get to the blood-brain barrier in greater amounts for better utilisation by the neurons. In the U.S., the AADC inhibitor of choice is carbidopa and in other countries it’s benserazide.

The discovery of dopamine agonists

Dopamine agonists are ‘mimics’ of dopamine that pass through the blood brain barrier to interact with target dopamine receptors. Since the mid-1970’s, dopamine agonists are often the first medication given most people to treat their Parkinson’s; furthermore, they can be used in conjunction with levodopa/carbidopa. The most commonly prescribed dopamine agonists in the U.S. are Ropinirole (Requip®), Pramipexole (Mirapex®), and Rotigotine (Neupro® patch). There are some challenging side effects of dopamine agonists including compulsive behaviour (e.g., gambling and hypersexuality), orthostatic hypotension, and hallucination.

The clinical use of MAO-B inhibitors

In the late-1970’s, monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors were created to block an enzyme in the brain that breaks down levodopa. MAO-B inhibitors have a modest effect in suppressing the symptoms of Parkinson’s. Thus, one of the functions of MAO-B inhibitors is to prolong the half-life of levodopa to facilitate its use in the brain. Very recently in clinical trials, it’s been shown that MAO-B inhibitors have some neuroprotective effect when used long-term. The most widely used MAO-B inhibitors in the U.S. include Rasagiline (Azilect) and Selegiline (Eldepryl and Zelpar); MAO-B inhibitors may reduce “off” time and extend “on” time of levodopa.

Fetal Cell transplantation

After successful preclinical experiments in rodents, a team of researchers in Sweden, led by Anders Bjorklund and Olle Lindvall, began the first clinical trials of fetal cell transplantation for Parkinson’s disease. These studies involved taking embryonic dopamine cells and injecting them into the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease. The cells then matured and replaced the cells that had been lost during the progression of the disease.

The discovery of MPTP

In July of 1982, Dr. J. William Langston of the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose (California) was confronted with a group of heroin addicts who were completely immobile. A quick investigation demonstrated that the ‘frozen addicts’ had injected themselves with a synthetic heroin that had not been prepared correctly. The heroin contained a chemical called MPTP, which when injected into the body rapidly kills dopamine cells. This discovery provided the research community with a new tool for modelling Parkinson’s disease.

1997-2006- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 1d: Historical):

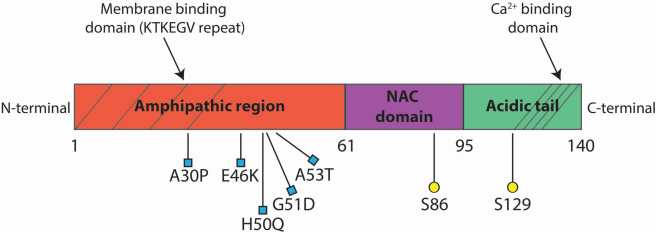

Alpha synuclein becomes the first gene associated with familial cases of Parkinson’s disease and its protein is found in Lewy bodies

In 1997, a group of researchers at the National institute of Health led by Robert Nussbaum reported the first genetic aberration linked to Parkinson’s disease. They had analysed DNA from a large Italian family and some Greek familial cases of Parkinson’s disease, and they

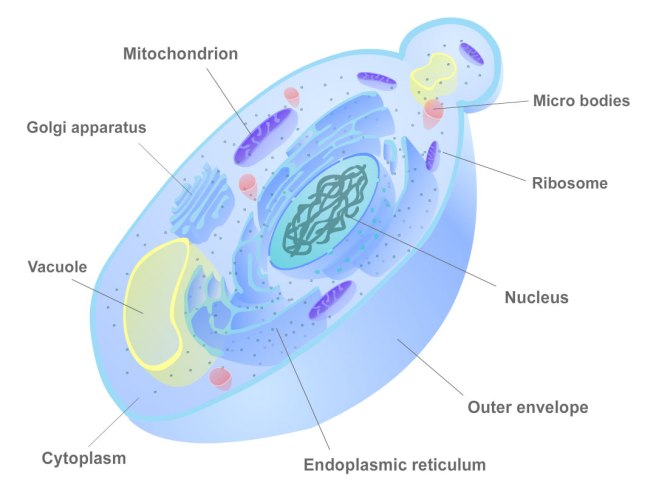

The gene Parkin becomes the first gene associated with juvenile Parkinson’s disease

The gene Parkin provides the instructions for producing a protein that is involved with removing rubbish from within a cell. In 1998, a group of Japanese scientists identified mutations in this gene that resulted in affected individuals being vulnerable to developing a very young onset (juvenile) version of Parkinson’s disease.

The first use of PET scan brain imaging for Parkinson’s disease

Using the injection of a small amount of radioactive material (known as a tracer), the level of dopamine present in an area of the brain called the striatum could be determined in a live human being. Given that amount of dopamine in the striatum decreases over time in Parkinson’s disease, this method of brain scanning represented a useful diagnostic aid and method of potentially tracking the condition.

The launch of Michael J Fox Foundation

In 1991, actor Michael J Fox was diagnosed with young-onset Parkinson’s disease at 29 years of age. Upon disclosing his condition in 1998, he committed himself to the campaign for increased Parkinson’s research. Founded on the 31st October, 2000, the Michael J Fox Foundation has funded more than $700 million in Parkinson’s disease research, representing one of the largest non-governmental sources of funding for Parkinson’s disease.

The Braak Staging of Parkinson’s pathology

In 2003, German neuroanatomist Heiko Braak and colleagues presented a new theory of how Parkinson’s disease spreads based on the postmortem analysis of hundreds of brains from people who had died with Parkinson’s disease. Braak proposed a 6 stage theory, involving the disease spreading from the brain stem (at the top of the spinal cord) up into the brain and finally into the cortex.

The gene DJ1 is linked to early onset PD

DJ1 (also known as PARK7) is a protein that inhibits the aggregation of Parkinson’s disease-associated protein alpha synuclein. In 2003, researchers discovered mutations in the DJ1 gene that made people vulnerable to a early-onset form of Parkinson’s disease.

The first GDNF clinical trial indicates neuroprotection in people with Parkinson’s disease

A small open-label clinical study involving the direct delivery of the chemical Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) into the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease indicated that neuroprotection. The subjects involved in the study exhibited positive responses to the treatment and postmortem analysis of one subjects brain indicated improvements in the brain.

The genes Pink1 and LRRK2 are associated with early onset PD

Early onset Parkinson’s is defined by age of onset between 20 and 40 years of age, and it accounts for <10% of all patients with Parkinson’s. Genetic studies are finding a causal association for Parkinson’s with five genes: alpha synuclein (SNCA), parkin (PARK2), PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), DJ-1 (PARK7), and Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2). However it happens, and at whatever age it occurs, there is no doubt that genetics and environment combine together to contribute to the development of Parkinson’s.

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cells

In 2006, Japanese researchers demonstrated that it was possible to take skin cells and genetically reverse engineer them into a more primitive state – similar to that of a stem cell. This amazing achievement involved a fully mature cell being taken back to a more immature state, allowing it to be subsequently differentiated into any type of cell. This research resulted in the discoverer, Shinya Yamanaka being awarded the 2012 Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine.

2007-2016- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 1e: Historical):

The introduction of the MDS-UPDRS revised rating scale

The Movement Disorder Society (MDS) unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) was introduced in 2007 to address two limitations of the previous scaling system, namely a lack of consistency among subscales and the low emphasis on the non-motor features. It is now the most commonly used scale in the clinical study of Parkinson’s disease.

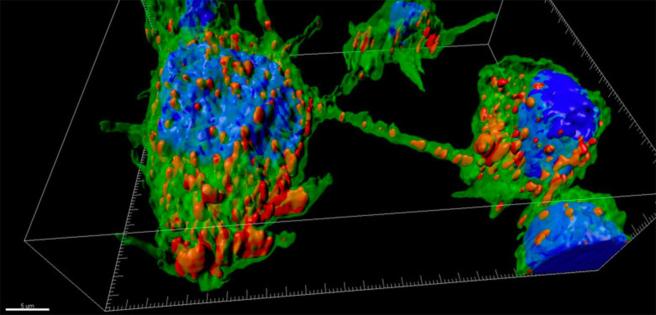

The discovery of Lewy bodies in transplanted dopamine cells

Postmortem analysis of the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease who had fetal cell transplantation surgery in the 1980-1990s demonstrated that Lewy bodies are present in the transplanted dopamine cells. This discovery (made by three independent research groups) suggests that Parkinson’s disease can spread from unhealthy cells to healthy cells. This finding indicates a ‘prion-like’ spread of the condition.

SNCA, MAPT and LRRK2 are risk genes for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease

Our understanding of the genetics of Parkinson’s is rapidly expanding. There is recent evidence of multiple genes linked to an increase the risk of idiopathic Parkinson’s. Interestingly, microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) is involved in microtubule assembly and stabilization, and it can complex with alpha synuclein (SNCA). Future therapies are focusing on the reduction and clearance of alpha synuclein and inhibition of Lrrk2 kinase activity.

IPS derived dopamine neurons from people with Parkinson’s disease

The ability to generate dopamine cells from skin cells derived from a person with Parkinson’s disease represents not only a tremendous research tool, but also opens the door to more personalized treatments of suffers. Induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cells have opened new doors for researchers and now that we can generate dopamine cells from people with Parkinson’s disease exciting opportunities are suddenly possible.

Neuroprotective effect of exercise in rodent Parkinson’s disease models

Exercise has been shown to be both neuroprotective and neurorestorative in animal models of Parkinson’s. Exercise promotes an anti-inflammatory microenvironment in the mouse/rat brain (this is but one example of the physiological influence of exercise in the brain), which helps to reduce dopaminergic cell death. Taking note of these extensive and convincing model system results, many human studies studying exercise in Parkinson’s are now also finding positive benefits from strenuous and regular exercise to better manage the complications of Parkinson’s.

Transeuro cell transplantation trial begins

In 2010, a European research consortium began a clinical study with the principal objective of developing an efficient and safe treatment methodology fetal cell transplantation in people with Parkinson’s disease. The trial is ongoing and the subjects will be followed up long term to determine if the transplantation can slow or reverse the features of Parkinson’s disease.

Successful preclinical testing of dopamine neurons from embryonic stem cells

Scientists in Sweden and New York have successfully generated dopamine neurons from human embryonic stem cells that can be successfully transplanted into animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Not only do the cells survive, but they also correct the motor deficits that the animals exhibit. Efforts are now being made to begin clinical trials in 2018.

Microbiome of the gut influences Parkinson’s disease

Several research groups have found the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein alpha synuclein in the lining of the gut, suggesting that the intestinal system may be one of the starting points for Parkinson’s disease. In 2016, researchers found that the bacteria in the stomachs of people with Parkinson’s disease is different to normal healthy individuals. In addition, experiments in mice indicated that the bacteria in the gut can influence the healthy of the brain, providing further evidence supporting a role for the gut in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

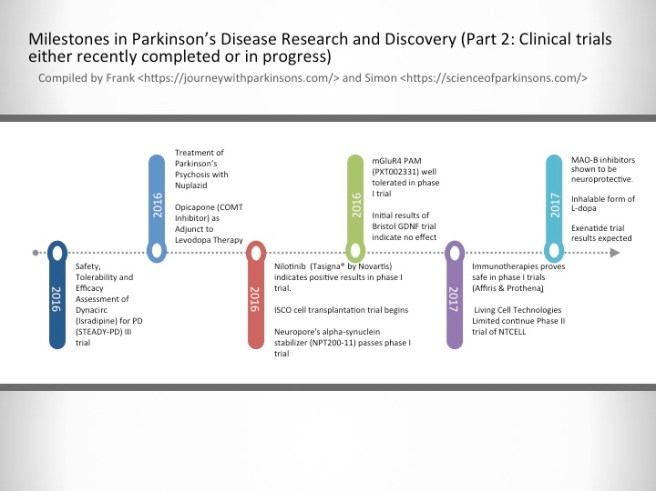

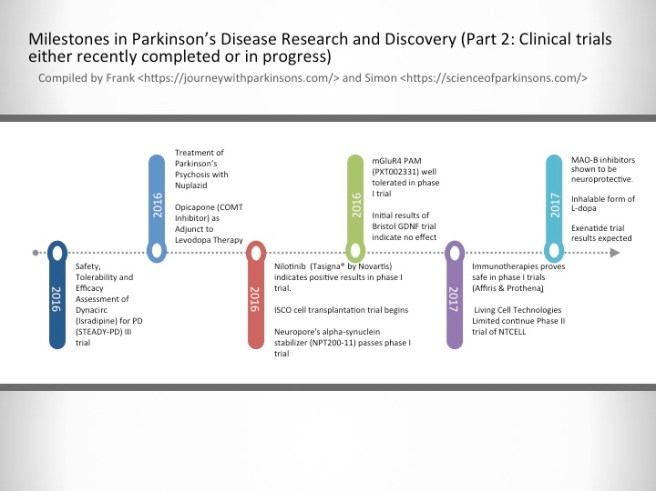

2016-2017- Milestones in Parkinson’s Disease Research and Discovery (Part 2: Clinical trials either recently completed or in progress)

Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy Assessment of Dynacirc (Isradipine) for PD (STEADY-PD) III trial

Isradipine is a calcium-channel blocker approved for treating high blood pressure; however, Isradipine is not approved for treating Parkinson’s. In animal models, Isradipine has been shown to slow the progression of PD by protecting dopaminergic neurons. This study is enrolling newly diagnosed PD patients not yet in need of symptomatic therapy. Participants will be randomly assigned Isradipine or given a placebo.

Treatment of Parkinson’s Psychosis with Nuplazid

Approximately 50% of the people with Parkinson’s develop psychotic tendencies. Treatment of their psychosis can be relatively difficult. However, a new drug named Nuplazid was recently approved by the FDA specifically designed to treat Parkinson’s psychosis.

Opicapone (COMT Inhibitor) as Adjunct to Levodopa Therapy in Patients With Parkinson Disease and Motor Fluctuations

Catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors prolong the effect of levodopa by blocking its metabolism. COMT inhibitors are used primarily to help with the problem of the ‘wearing-off’ phenomenon associated with levodopa. Opicapone is a novel, once-daily, potent third-generation COMT inhibitor. It appears to be safer than existing COMT drugs. If approved by the FDA, Opicapone is planned for use in patients with Parkinson’s taking with levodopa who experience wearing-off issues.

Nilotinib (Tasigna® by Novartis) indicates positive results in phase I trial.

Nilotinib is a drug used in the treatment of leukemia. In 2015, it demonstrated beneficial effects in a small phase I clinical trial of Parkinson’s disease. Researchers believe that the drug activates the disposal system of cells, thereby helping to make cells healthier. A phase II trial of this drug to determine how effective it is in Parkinson’s disease is now underway.

ISCO cell transplantation trial begins

International Stem Cell Corporation is currently conducting a phase I clinical cell transplantation trial at a hospital in Melbourne, Australia. The company is transplanting human parthenogenetic stem cells-derived neural stem cells into the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease. The participants will be assessed over 12 months to determine whether the cells are safe for use in humans.

Neuropore’s alpha-synuclein stabilizer (NPT200-11) passes phase I trial

Neuropore Therapies is a biotech company testing a compound (NPT200-11) that inhibits and stablises the activity of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein alpha synuclein. This alpha-synuclein inhibitor has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in humans in a phase I clinical trial and the company is now developing a phase II trial.

mGluR4 PAM (PXT002331) well tolerated in phase I trial

Prexton Therapeutics recently announced positive phase I clinical trial results for their lead drug, PXT002331, which is the first drug of its kind to be tested in Parkinson’s disease. PXT002331 is a mGluR4 PAM – this is a class of drug that reduces the level of inhibition in the brain. In Parkinson’s disease there is an increase in inhibition in the brain, resulting in difficulties with initiating movements. Phase II clinical trials to determine efficacy are now underway.

Initial results of Bristol GDNF trial indicate no effect

Following remarkable results in a small phase I clinical study, the recent history of the neuroprotective chemical GDNF has been less than stellar. A subsequent phase II trial demonstrated no difference between GDNF and a placebo control, and now a second phase II trial in the UK city of Bristol has reported initial results also indicating no effect. Given the initial excitement that surrounded GDNF, this result has been difficult to digest. Additional drugs that behave in a similar fashion to GDNF are now being tested in the clinic.

Immunotherapies proves safe in phase I trials (AFFiRis & Prothena)

Immunotherapy is a treatment approach which strengthens the body’s own immune system. Several companies (particularly ‘AFFiRis’ in Austria and ‘Prothena’ in the USA) are now conducting clinical trials using treatments that encourage the immune system to target the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein alpha synuclein. Both companies have reported positive phase I results indicating the treatments are well tolerable in humans, and phase II trials are now underway.

Living Cell Technologies Limited continue Phase II trial of NTCELL

A New Zealand company called Living Cell Technologies Limited have been given permission to continue their phase II clincial trial of their product NTCELL, which is a tiny capsule that contains cells which release supportive nutrients when implanted in the brain. The implanted participants will be blindly assessed for 26 weeks, and if the study is successful, the company will “apply for provisional consent to treat paying patients in New Zealand…in 2017”.

MAO-B inhibitors shown to be neuroprotective.

MAO-B inhibitors block/slow the break down of the chemical dopamine. Their use in Parkinson’s disease allows for more dopamine to be present in the brain. Recently, several longitudinal studies have indicated that this class of drugs may also be having a neuroprotective effect.

Inhalable form of L-dopa

Many people with Parkinson’s disease have issues with swallowing. This makes taking their medication in pill form problematic. Luckily, a new inhalable form of L-dopa will shortly become available following recent positive Phase III clinical trial results, which demonstrated a statistically significant improvements in motor function for people with Parkinson’s disease during OFF periods.

Exenatide trial results expected

Exenatide is a drug that is used in the treatment of diabetes. It has also demonstrated beneficial effects in preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease, as well as an open-label clinical study over a 14 month period. Interestingly, in a two year follow-up study of that clinical trial – conducted 12 months after the patients stopped receiving Exenatide – the researchers found that patients previously exposed to Exenatide demonstrated significant improvements compared to how they were at the start of the study. There is currently a placebo-controlled, double blind phase II clinical trial being conducted and the results should be reported before the end of 2017.

A personal reflection

As I suggested at the start of this post, this endeavour was entirely Frank’s idea – full credit belongs with him. I was more than happy to help him out with it though as I thought it was a very worthy project. During this 200 year anniversary, I believe it is very important to acknowledge just how far we have come in our understanding of Parkinson’s disease since James first put pen to paper and described the six cases he had seen in London.

And Frank’s idea perfectly captures this.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Greg Dunn (we are big fans!)

For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the

For today’s post, we have teamed up with Prof Frank Church from the