|

# # # # At the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in October 2015, the results of a small phase 1 clinical study were presented and the Parkinson’s community got rather excited by what they saw. The study had investigated a cancer drug called ‘nilotinib’ (also known as Tasigna) on 12 people with advanced Parkinson’s or Dementia with Lewy bodies. After 6 months of treatment, the participants reported that they were functioning better on nilotinib. Two larger, more carefully controlled phase 2 clinical trials of nilotinib in people with Parkinson’s were conducted, and both studies could not replicate the original findings (worse: the drug was barely detected in the brain). But now a biotech company called Inhibikase has developed a nilotinib-like agent that can access the brain and they are clinically testing it. This week they published preclinical data on their lead agent, IkT-148009. In today’s post, we will look at the history of this story, review the recently published preclinical research from Inhibikase, and discuss the current clinical trial. # # # # |

Source: Wiki

Source: Wiki

Cancer.

There’s a happy topic to start a post with.

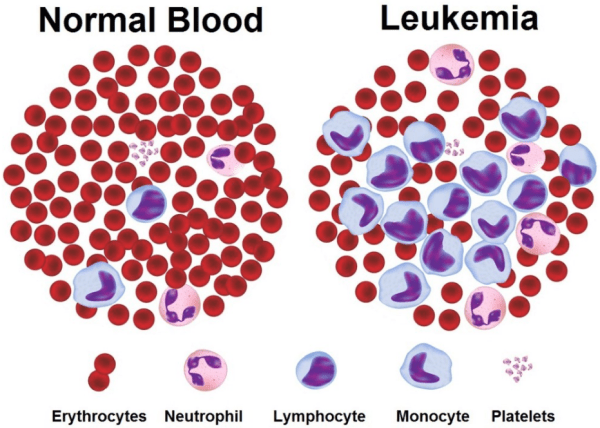

Cancer is a condition where cells in a specific part of the body start to grow and reproduce uncontrollably. There are lots of different types of cancers, but I would like to draw your attention to one in particular: Leukemia

Leukemia is a particular branch of cancer. It is a broad term used for cancers of the body’s blood-forming tissues (these include the bone marrow and the lymphatic system).

The type of leukemia diagnosed depends entirely on the type of blood cell that becomes cancerous and on whether it grows quickly or slowly. Leukemia occurs most often in adults older than 55, but it is also the most common cancer in children younger than 15.

There are approximately 10,000 new cases of leukemia (that’s 27 every day), and ~5000 deaths associated with the condition in the UK (Click here for the source of these figures).

Interesting, but why are you starting this post by talking about leukemia?

Well, there are many different kinds of leukemia, but for today’s post we are going to need to understand the biology associated with one particular type, called chronic myelogenous leukemia (or CML).

And what is chronic myelogenous leukemia?

It is a very rare form of leukemia, characterized by the unchecked proliferation of myeloid cells in the bone marrow and the accumulation of these cells in the blood.

CML is a clonal bone marrow stem cell disorder in which a proliferation of mature granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils) and their precursors is found.

What does CML have to do with Parkinson’s?

Well, CML happens when something really strange happens in bone marrow cells: New chromosomes develops

What is a chromosome?

In a nutshell, a chromosome is a very efficient way of packing a lot of DNA into a cell.

Within most of the cells in your body, DNA is densely coiled into discrete packages called chromosomes. Without such packaging, the stringy DNA molecules would be too long to fit inside the cell. In fact, if you uncoiled all of the DNA molecules in a single human cell and placed them end-to-end, they would stretch for at least 6 feet. And that’s just for one cell – consider that humans have approx. 70 trillion cells in their body!

A schematic demonstrating the arrangement of DNA- Genes-Chromosomes. Source: cancergenome.nih.gov

A schematic demonstrating the arrangement of DNA- Genes-Chromosomes. Source: cancergenome.nih.gov

When a cell is not dividing, the chromosomes usually sit in the nucleus of the cell in loose strands called chromatin. When the cell decides to divide, the chromatin condenses and wrap up very tightly, becoming chromosomes. Both loose chromatin and tightly wound chromosomes are very difficult to see, even with a microscope.

Chromosomes come in pairs – one set of 23 chromosomes from each parent, giving us a total of 46 chromosomes per cell.

These chromosomes hold the DNA – a complex set of instructions that tell the cells what to do. When CML starts in a blood cell, a section of chromosome 9 switches places with a section of chromosome 22. This creates a shorter chromosome 22 (called the Philadelphia chromosome – named for the city where it was discovered) and a longer chromosome 9. In other words, two large chunks of DNA are switched, shifting from one location on your DNA to another.

Philadelphia chromosome. Source: Wikipedia

Clever trick huh?

The result of this mix up is what we call a ‘fusion gene’ on chromosome 22, which is created by shifting of the ABL1 gene from chromosome 9 (region q34) to a part of the BCR gene on chromosome 22 (region q11).

This leads to a weird fusion protein called BCR-ABL.

Now, the really curious part of this development is that this protein is still able to function!

In fact, it undertakes a variety of functions. But the problem with this situation is that the BCR-ABL fusion protein is always turned on.

It is always active.

Think of that bull in a China shop analogy,… but the bull is high on amphetamine!

And this constant activity helps to drive the cancer cell growth in blood cells.

Are we getting to the Parkinson’s stuff soon?

Yes, I beg a little more patience.

Initially, a cancer ‘wonder drug’ called imatinib (also known as Gleevec) was developed to block the BCR-ABL fusion protein from binding to other proteins that help to encourage the cancer growth. It competitively binds to a small region of the BCR-ABL fusion protein, not allowing (or blocking) it to fulfil its hyperactive function.

How Imatinib (aka Gleevec) works in cancer. Source: Wikipedia

It is hard to understate how fantastic imatinib was. It was an amazing example of precision drug design. The researchers went into the project with a very specific target and were able to hit it quite precisely. One issue, however, with imatinib was it’s potency.

So the researchers went back to the drawing board and identified a new and improved version of the agent, which they called nilotinib (remember this drug, it’s important). It is very similar to imatinib – in shape and function – and it is used for people who fail to respond to imatinib. Importantly, nilotinib is 10-30 times more potent than imatinib at inhibiting BCR-ABL activity.

And this is where we finally get to Parkinson’s.

What do you mean? Is the fusion protein ‘BCR-ABL’ involved?

No, there is no ‘fusion gene’ or ‘fusion protein’ associated with Parkinson’s.

Rather, while the drugs nilotinib and imatinib were originally designed to target the BCR-ABL fusion protein, both drugs can also be used to block the ABL protein by itself.

OK, but how is that relevant to Parkinson’s?

It has been suggested that the activation of the ABL1 gene may be playing a role in neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Click here for the Alzheimer’s related research and click here for an early review on this topic).

This idea is also supported in Parkinson’s, because in 2010 by a group of researchers publishing a paper demonstrating that there is increased levels of ABL protein in the Parkinsonian brain, and by blocking the ABL protein, imatinib could effectively protect models of Parkinson’s.

Here is that research report:

Title: Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin’s ubiquitination and protective function.

Authors: Ko HS, Lee Y, Shin JH, Karuppagounder SS, Gadad BS, Koleske AJ, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC,Dawson VL, Dawson TM.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Sep 21;107(38):16691-6.

PMID: 20823226 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers reported that inside cells, the ABL protein binds to and interacts with the Parkinson’s associated protein PARKIN. But this interaction is not a good one: ABL basically stops PARKIN from having doing its job – that is, waste disposal/recycling in a process called autophagy.

Autophagy is a process that clears waste and old proteins from inside cells, preventing them from accumulating and possibly causing the death of the cell.

The process of autophagy. Source: Wormbook

Waste material inside a cell is collected in membranes that form sacs (called vesicles). These vesicles then bind to another sac (called a lysosome) which contains enzymes that will breakdown and degrade the waste material. When PARKIN is inhibited, normal autophagy does not take place and old proteins and faulty mitochondria start to pile up, making the cell sick (ultimately leading to the death of the cell).

The researchers found that cells treated with a neurotoxin (MPTP) had high levels of activated ABL protein, and by blocking this ABL protein they could reduce the effect of the neurotoxin (in a fashion that was dependent on PARKIN being present). They also showed that genetically engineered mice with no ABL gene were more resistant to the neurotoxin than normal mice. Importantly, they provided data indicating that the inactivated form of PARKIN and the activated version of ABL are higher in the brains of people with Parkinson’s than normal controls.

The investigators concluded that “inhibition of ABL may be a neuroprotective approach in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease”. And critically many of these findings were replicated independently by another research group shortly after this first report was published (Click here to read that second research report).

These initial imatinib results were followed up a couple of years later by a research team at Georgetown University, but this time the researchers were using the new and improved version of an ABL inhibitor: nilotinib.

Title: Nilotinib reverses loss of dopamine neurons and improves motor behavior via autophagic degradation of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease models.

Authors: Hebron ML, Lonskaya I, Moussa CE.

Journal: Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Aug 15;22(16):3315-28.

PMID: 23666528 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators demonstrated that levels of activated ABL protein increase with accumulation of the Parkinson’s associated protein Alpha Synuclein – accumulation of which is a characteristic feature of the Parkinsonian brain.

By giving nilotinib to mice that had been genetically engineered to produce high levels of alpha synuclein, the researchers found that they could reduce the negative effects of the accumulating protein. They also demonstrated that the positive effect of nilotinib treatment was produced (in part) by the activation of the garbage disposal system (autophagy) and removal of the accumulating alpha synuclein.

In another experiment in that same report, when they modelled the accumulation of alpha synuclein in dopamine neurons, the researchers found that nilotinib treatment could protect the dopamine cells from dying and corrected dopamine levels back to normal. And this research group also demonstrated elevated levels of ABL protein in the Parkinsonian brain when compared to normal controls. They concluded that the “data suggest that nilotinib may be a therapeutic strategy to degrade alpha synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and other alpha synucleinopathies”.

And importantly, these results have been replicated by other independent research groups. Firstly by a Swiss group that found that ABL protein binds to and interacts with alpha synuclein:

Title: c-Abl phosphorylates α-synuclein and regulates its degradation: implication for α-synuclein clearance and contribution to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Mahul-Mellier AL, Fauvet B, Gysbers A, Dikiy I, Oueslati A, Georgeon S, Lamontanara AJ, Bisquertt A, Eliezer D, Masliah E, Halliday G, Hantschel O, Lashuel HA.

Journal: Hum Mol Genet. 2014 Jun 1;23(11):2858-79.

PMID: 24412932 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

These Swiss researchers also reported raised levels of ABL protein in the brains of people with Parkinson’s, AND their results supported the findings that nilotinib encourages degradation of alpha synuclein protein. Interestingly, they also found that nilotinib reduced levels of ABL protein itself (via the autophagy pathway).

The second research group to independently reproduce the nilotinib results was the group behind the original imatinib in PD models results:

Title: The c-Abl inhibitor, nilotinib, protects dopaminergic neurons in a preclinical animal model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Karuppagounder SS, Brahmachari S, Lee Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ko HS

Journal: Sci Rep. 2014 May 2;4:4874.

PMID: 24786396 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers found that nilotinib treatment protected dopamine neurons in a model of Parkinson’s and restored normal dopamine levels in the brain. They also found that administration of nilotinib reduces ABL activation and the levels of the PARKIN interacting protein PARIS (or PARkin Interacting Substrate).

High levels of PARIS in normal mice can result in the loss of dopamine cells, and this effect can be rescued by increased production of PARKIN protein (We have discussed PARIS in a previous post – click here to read that post).

All of these studies provided a strong rationale for testing brain permeable ABL inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of Parkinson’s (For those seeking more information about the research of nilotinib and other ABL inhibitors in Parkinson’s models – click here for a good review).

|

# RECAP #1: ABL is a protein that is hyperactive in the brains of people with Parkinson’s, and it interacts with proteins associated with the condition. Inhibition of ABL (using cancer drugs like nilotinib) reduces neurodegeneration in models of Parkinson’s. # |

And Nilotinib has been tested in people with Parkinson’s?

Yes.

The Georgetown researchers who conducted the original nilotinib in PD models studies – led by Dr Charbel Moussa and Dr Fernando Pagan – undertook a small clinical pilot study.

Dr Charbel Moussa and Dr Fernando Pagan. Source: Georgetown

And the results of this study have been published:

Title: Nilotinib Effects in Parkinson’s disease and Dementia with Lewy bodies

Authors: Pagan F, Hebron M, Valadez E, Tores-Yaghi Y,Huang X, Mills R, Wilmarth B, Howard H, Dunn C, Carlson A, Lawler A, Rogers S, Falconer R, Ahn J, Li Z, & Moussa C.

Journal: Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, 2016 Jul 11;6(3):503-17.

PMID: 27434297 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it).

Twelve people with either Parkinson’s dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies were randomised given either 150 mg (n = 5) or 300 mg (n = 7) daily doses of nilotinib for 24 weeks. After the treatment period, the participants were followed up for another 12 weeks. All of the participants were considered to have mid to late stage Parkinson’s features (Hoehn and Yahr stage 3–5). One individual was withdrawn from the study at week 4 due to a heart attack and another discontinued at 5 months due to unrelated circumstances.

An important question in the study was whether nilotinib could actually enter the brain. Various tests conducted on the participants suggested that the drug was crossing the blood brain barrier and having an effect in the brain (this study reported the “CSF:plasma ratio of nilotinib is 12% and 5% with 300 mg and 150 mg nilotinib, respectively“. The levels of nilotinib in the brain peaked at 2 hours after taking the drug and the levels of ABL protein were reduced by 30% at 1 hr. This level of activity remained stable for several hours.

The motor features of Parkinson’s were assessed using the standard Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and the investigators observed an average decrease of 3.4 points and 3.6 points at six months (week 24) compared to the baseline measures (scores from the start of the study) with 150 mg and 300 mg nilotinib, respectively. A decrease in motor scores represent an improvement in Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

The really remarkable result, however, came from the testing of cognitive performance, which was monitored with Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE). The researchers report an average increase of 3.85 and 3.5 points in MMSE at six months (24-week) compared to baseline, for 150 mg and 300 mg of nilotinib, respectively. This suggests that the mental processing of the participants also improved across the study (IMPORTANT NOTE: this was an open-label trial, so everyone in the study knew that they were taking the treatment, including the investigators – there was no placebo treated group).

The researchers concluded that these observations warrant a larger randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to truly evaluate the safety and efficacy of Nilotinib.

This all sounds great. What happened next?

The Georgetown University team initiated a larger Phase 2 trial back in February 2017. It was called the ‘PD Nilotinib’ study and it involved two parts.

Georgetown University (Washington DC). Source: Wallpapercave

In the first part of the study, one third of the participants received a low dose (150mg) of nilotinib, another third received a higher dose (300mg) and the final third were administered a placebo drug (a drug that has no bioactive effect to act as a control against the other two groups). The outcomes were assessed clinically at six and 12 months by investigators who are blind to the treatment of each participant. These results were compared to clinical assessments made at the start (or baseline) of the study.

In the second part of the study, there was a one-year open-label extension trial, in which all participants were randomised to either the low dose (150mg) or high dose (300mg) of nilotinib. This extension started upon the completion of the first part of the study (the placebo-controlled trial outlined above) to evaluate nilotinib’s long-term effects (Click here for more details on the study).

The Georgetown study recruited 75 participants and randomly assigned them to the three groups. The results of the study were published in 2020:

Title: Nilotinib Effects on Safety, Tolerability, and Potential Biomarkers in Parkinson Disease: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial.

Title: Nilotinib Effects on Safety, Tolerability, and Potential Biomarkers in Parkinson Disease: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial.

Authors: Pagan FL, Hebron ML, Wilmarth B, Torres-Yaghi Y, Lawler A, Mundel EE, Yusuf N, Starr NJ, Anjum M, Arellano J, Howard HH, Shi W, Mulki S, Kurd-Misto T, Matar S, Liu X, Ahn J, Moussa C.

Journal: JAMA Neurol. 2020 Mar 1;77(3):309-317.

PMID: 31841599 (this report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

A total of 66 participants finished the 12-month double blind portion of the study. In Part 1 of the study, nilotinib was found to be safe and reasonably well tolerated (although more serious adverse events occurred in the nilotinib groups (150 mg: n=6 serious adverse events; 300 mg: n=12) compared to the placebo group (n=4). Unfortunately, “no statistically significant differences in MDS-UPDRS measurements were observed between groups” (indicating that the investigators recorded no difference in clinical scores over the 12 month blinded study):

And strangely, “pharmacokinetic data indicate that small amounts of nilotinib are detected in the CSF at 12 months in a dose-dependent manner. The CSF/plasma ratio of nilotinib is less than 1%“. This suggests that only tiny amounts of the drug were able to access the brain – much less than the amounts reported in the previous pilot study discussed above. Why such a large difference was observed between the studies is not clear – the participants were of a similar stage in the PD, so it is very strange.

The results of the extension arm of this study (Part 2), have also been published. I think it is fair to say that (in the absence of a placebo comparator) the results were mixed (Click here to read them).

Oh dear. Has there been another clinical trial of nilotinib in PD?

Yes, there has.

In parallel to the Georgetown study, there was a second Phase 2 clinical trial investigating nilotinib in a Parkinson’s cohort. Called ‘NILO-PD’, this study was carried out at 25 different clinical sites across the USA through the Parkinson Study Group, which is the largest not-for-profit network of Parkinson’s centres in North America.

Similar to the Georgetown PD-NILO study, 75 participants with moderate to advanced Parkinson’s were randomly assigned to receive either a daily dose of 150 mg of Nilotinib, 300 mg of Nilotinib or placebo. The treatments were given everyday for six months, during which the participants were closely monitored. Following the treatment phase, there was an 8-week follow up period (during which all study-related treatments were stopped (Click here to read more about the details of this study).

The results of this study have also been published:

Title: Efficacy of Nilotinib in Patients With Moderately Advanced Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Title: Efficacy of Nilotinib in Patients With Moderately Advanced Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Authors: Simuni T, Fiske B, Merchant K, Coffey CS, Klingner E, Caspell-Garcia C, Lafontant DE, Matthews H, Wyse RK, Brundin P, Simon DK, Schwarzschild M, Weiner D, Adams J, Venuto C, Dawson TM, Baker L, Kostrzebski M, Ward T, Rafaloff G; Parkinson Study Group NILO-PD Investigators and Collaborators.

Journal: JAMA Neurol. 2021 Mar 1;78(3):312-320.

PMID: 33315105 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

Similar to the Georgetown study, the results of this second trial found “no evidence of symptomatic benefit of nilotinib on any measures of PD disability“. The clinical scores between the groups did not change much over the 6 month study:

And in this study, the researchers found that nilotinib levels in cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid our brains sit in) were less than 0.3% of that in the serum/blood, indicating that very little of the drug is accessing the brain. Given these results, the investigators concluded “further testing of nilotinib in treatment of Parkinson disease is not warranted”.

|

# # RECAP #2: An early open-label pilot clinical study data indicated that the ABL inhibitor nilotinib was safe and tolerable in people with Parkinson’s. There were also signs of beneficial effects. Subsequent larger and more carefully controlled studies found no positive effects, and suggest that the drug barely gets into the brain. # # |

Oh dear, oh dear. So what does it all mean?

Well, if you want my opinion, I think it means that despite some encouraging open label pilot study results, it looks like nilotinib is not the right drug to test whether ABL inhibition is a therapeutic approach for Parkinson’s. If it is not getting into the brain, we need to find better agents to test the ABL theory.

And there are a number of research groups that agree with this idea.

One example is a biotech company called Inhibikase Therapeutics.

Founded in 2008, the company has been developing CNS-penetrant ABL inhibitors. They recently published preclinical data on their primary clinical agent risvodetinib (also known as IkT-148009).

Founded in 2008, the company has been developing CNS-penetrant ABL inhibitors. They recently published preclinical data on their primary clinical agent risvodetinib (also known as IkT-148009).

Here is the report:

Title: The c-Abl inhibitor IkT-148009 suppresses neurodegeneration in mouse models of heritable and sporadic Parkinson’s disease.

Title: The c-Abl inhibitor IkT-148009 suppresses neurodegeneration in mouse models of heritable and sporadic Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Karuppagounder SS, Wang H, Kelly T, Rush R, Nguyen R, Bisen S, Yamashita Y, Sloan N, Dang B, Sigmon A, Lee HW, Marino Lee S, Watkins L, Kim E, Brahmachari S, Kumar M, Werner MH, Dawson TM, Dawson VL.

Journal: Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jan 18;15(679):eabp9352.

PMID: 36652533

In this study, the researchers investigated IkT-148009 in mouse models of Parkinson’s and found to be neuroprotective – even when treatment started 4-weeks after the symptoms of the PD model appeared.

These results support the clinical research that Inhibikase has initiated. Between 2017-2019, the company conducted three Phase 1 studies testing of IkT-148009, which included testing the drug in Parkinson’s patients once a day for 7 days (Click here to read more about this study).

The results of these studies have not been published, but here is Dr Milton Werner – Chief Executive Officer of Inhibikase Therapeutics – discussing the findings of the Phase 1 studies and their future plans:

The company now has a 12-week study Phase 2 clinical trial assessing IkT-148009 in 120 participants with untreated Parkinson’s (meaning that they have been diagnosed, but are not being treated with L-dopa therapies – Click here to read more about this study). The study is ongoing and scheduled to finish in early 2025.

For those seeking more information about Inhibikase, you might like to watch this key opinion leaders webinar on their research:

Is Inhibikase the only biotech company testing an ABL inhibitor in Parkinson’s?

No. In fact, one company is further along than Inhibikase with developing an ABL inhibitor for Parkinson’s.

In 2019, Sun Pharma Advanced Research Company (SPARC) started a Phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled study of their ABL inhibitor, Vodobatinib (also known as K0706) in 506 individuals with recently diagnosed Parkinson’s.

This Phase 2 study consists of 2 components. The first (Part 1) involves evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of two different doses of vodobatinib (compared to placebo) in individuals with early, un-treated Parkinson’s. The second component (Part 2) is a long term extension study for participants who have completed week 40 of the first component (Click here to read more about this study). The study is ongoing and scheduled to complete in mid-2024.

The company has published the results of their Phase 1 testing which was conducted between 2017-2019.

Here is the report:

Title: Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of vodobatinib, a neuroprotective c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of vodobatinib, a neuroprotective c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Walsh RR, Damle NK, Mandhane S, Piccoli SP, Talluri RS, Love D, Yao SL, Ramanathan V, Hurko O.

Journal: Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023 Mar;108:105281.

PMID: 36717298 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The study found that short-term use of vodobatinib was well tolerated in 60 individuals with Parkinson’s. They reported that administration of three different doses of vodobatinib (48, 192 and 384 mg) to healthy volunteers for 1 week resulted in dose-increasing levels of the agent in the CSF (1.8, 11.6, and 12.2 nM, respectively), with the two highest doses being above the level required for inhibitory activity.

The investigators also presented in vitro data demonstrating that vodobatinib was more potent (kinase IC50 = 0.9 nM) than nilotinib (kinase IC50 = 15–45 nM), so hopefully vodobatinib and IkT-148009 will be able to access the brain well enough to finally provide a proper testing of the theory that ABL over activity is involved with the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s.

So what does it all mean?

There are few positives to having Parkinson’s, but one of the under appreciated aspects of the condition is the number of interesting biological pathways being targeted in clinical trials. When we compare PD with other neurodegenerative conditions (like Alzheimer’s or ALS), in my opinion there are a lot more viable targets being evaluated in Parkinson’s (think of LRRK2, alpha synuclein, Gcase, etc).

And one of those interesting targets is ABL.

Multiple independent research groups have demonstrated that ABL levels are elevated in the Parkinsonian brain, and that ABL inhibition is neuroprotective in models of PD. While the clinical trial results thus far have been mixed, one could easily argue that the agent used to test the target up till now has not been ideal. Luckily, biotech companies have been working on brain penetrant ABL inhibitors and they are now clinically testing them. Here at the SoPD HQ we will be watching these trials very carefully and look forward to seeing their final results.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from