|

# # # # The discovery of genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s has been very useful for the research community as they point towards associated biological pathways that could potentially be targeted for therapeutic intervention. They also represent a topic of concern for the Parkinson’s community, who worry about passing on possible risk to their children and subsequent generations. The penetrance (which refers to the proportion of people with a particular genetic variant who ever actually exhibit signs and symptoms of a particular condition) of many of these risk factors has, however, been found to be mixed, which has helped to confuse the matter. Recently, researchers have been exploring assays and biomarkers related to some of these genetic risk factors to see if we can determine who is likely to go on and develop Parkinson’s compared to “non-manifesting carriers” of the genetic risk factors. In today’s post, we will discuss what is meant by terms like “penetrance” and “non-manifesting carriers”, and we will review some of the latest research in this area. # # # # |

Source: Businesstoday

Source: Businesstoday

This year represents the 25th anniversary since the discovery that tiny variations in a region of DNA called the “PARKIN gene” may increase the risk of developing Parkinson’s.

On the 9th April, 1998, this report was published in the journal Nature:

Title: Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism.

Title: Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism.

Authors: Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N

Journal: Nature. 1998 Apr 9; 392(6676):605-8

PMID: 9560156

This study highlighted 5 cases of ‘juvenile’ Parkinsonism from three unrelated Japanese families, in which genetic variations were found in the PARKIN gene. This finding came less than a year after the first genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s – in the alpha synuclein gene – had been announced (Click here to read a SoPD post about this).

It was an exciting time for Parkinson’s research as these new risk factors were pointing towards particular biological pathways that could be explored in the context of Parkinson’s (and manipulated for potentially therapeutic purposes).

Over the next 10-15 years, there was a genetic gold rush as researchers identified over 80 regions of DNA in which genetic variations (tiny alterations in the G,A,T & C coding) that increased one’s risk of developing PD (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic).

But rather than being a genetic disease (a condition driven by a specific genetic cause), it quickly became apparent that the level of penetrance in Parkinson’s was not 100%, and questions started to be asked as to why.

What do you mean by “penetrance”?

The term ‘penetrance’ refers to the proportion of people who carry a particular genetic variant in their DNA who go on to actually present signs or symptoms of a genetic condition. If everyone who carries a particular genetic variation develops a condition, the penetrance of that genetic risk factor is considered very high. But if only half of the people with a particular genetic variation ultimately develop the features of the associated disorder, the condition is described as having reduced (or incomplete) penetrance.

And where penetrance is considered incomplete, the people who are carrying the genetic variation and not developing the condition are described as ‘non-manifesting carriers‘.

This sounds complicated. Can you provide me with an example?

Yes.

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition which results in individuals losing all inhibition of movement, giving rise to appearance of chorea – jerky, random, and uncontrollable movements (similar to dykinesias).

Importantly, Huntington’s disease is a genetic condition – caused by an expansion of a region of DNA in the Huntingtin (Htt) gene.

You will remember that DNA is made up of a four letter coding system that involves As, Ts, Gs, and Cs.

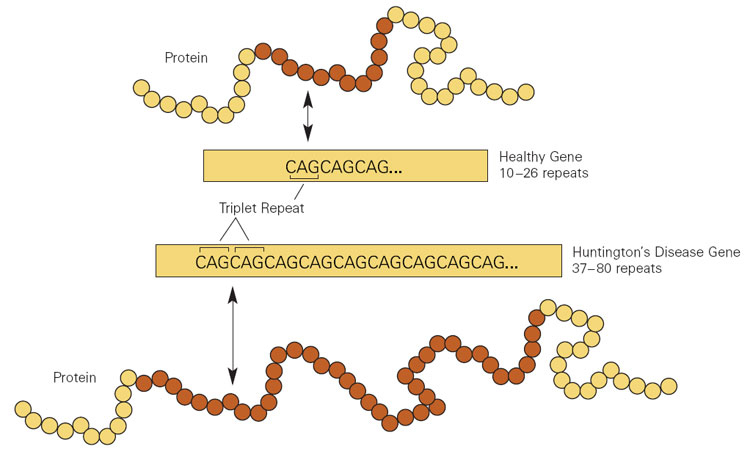

In the Huntingtin (Htt) gene, there is an area of DNA that is made up of CAG repeats. In normal healthy humans, we usually have up to 30 repeats of CAG. But if you have more than 40 CAG repeats, you are definitely going to develop Huntington’s disease.

Expansion of CAGs in the Huntingtin gene. Source: NIST

This means that Huntington’s disease is fully penetrant.

If you have more than 40 CAG repeat, you are 100% going to develop the condition.

And the genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s are not fully penetrant?

No, they are not.

Take for example the most common genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s: Between 5-10% of the Parkinson’s-affected population carry a genetic variation in their GBA1 gene. Over 300 genetic variants have been associated with increased risk of developing Gaucher disease or Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this).

And it is estimated that about 1 in 100 individuals in the general population (and 1 in 18 individuals with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry) carry a GBA1 gene variant.

But if 1% of the world’s population carries a GBA1 variant, why don’t more people have Parkinson’s???

Because the penetrance of GBA1 variants is rather low (or incomplete).

The probability of someone with a GBA1 variant actually developing Parkinson’s is ~10% by the age of 60, and ~25% by the age of 80 (Click here and here to read more about this).

Genetic variations in the LRRK2 gene (another gene associated with Parkinson’s) appear to be similar:

Title: Penetrance estimate of LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation in individuals of non-Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

Title: Penetrance estimate of LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation in individuals of non-Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

Authors: Lee AJ, Wang Y, Alcalay RN, Mejia-Santana H, Saunders-Pullman R, Bressman S, Corvol JC, Brice A, Lesage S, Mangone G, Tolosa E, Pont-Sunyer C, Vilas D, Schüle B, Kausar F, Foroud T, Berg D, Brockmann K, Goldwurm S, Siri C, Asselta R, Ruiz-Martinez J, Mondragón E, Marras C, Ghate T, Giladi N, Mirelman A, Marder K; Michael J. Fox LRRK2 Cohort Consortium.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2017 Oct;32(10):1432-1438.

PMID: 28639421 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the scientists reported that the penetrance of the most common LRRK2 genetic variant (G2019S) was estimated to be only 26% in Ashkenazi Jewish carriers by the age of 80 years:

Source: Semanticscholar (dashed line represent confidence intervals)

Source: Semanticscholar (dashed line represent confidence intervals)

But the penetrance of the LRRK2-G2019S variant appears to be extremely variable. When the researchers looked at risk in non-Ashkenazi Jewish carriers they found that the risk of Parkinson’s increased to 42% by 80 years of age (Click here to read a review on LRRK2 penetrance).

All of these statistics obviously beg the question: What factors are increasing the risk of developing Parkinson’s among genetic variant carriers?

What is happening in the lives of those variant carriers who develop Parkinson’s compared to those carriers who do not? Is there something in their personal biology that makes them even more vulnerable? Or is there something in their environment?

A recently published study has been exploring this idea in PARKIN variant carriers:

Title: Molecular phenotypes of mitochondrial dysfunction in clinically non-manifesting heterozygous PRKN variant carriers.

Title: Molecular phenotypes of mitochondrial dysfunction in clinically non-manifesting heterozygous PRKN variant carriers.

Authors: Castelo Rueda MP, Zanon A, Gilmozzi V, Lavdas AA, Raftopoulou A, Delcambre S, Del Greco M F, Klein C, Grünewald A, Pramstaller PP, Hicks AA, Pichler I.

Journal: NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2023 Apr 18;9(1):65.

PMID: 37072441 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers collected blood from 20 individuals – 11 were carriers of a heterozygous PRKN exon 7 deletion and 9 were unaffected controls.

Hang on a second. What the devil does “hetero-whatever PRKN exon 7 deletion” mean?

PRKN is the region in human DNA that provides the instructions for making PARKIN protein. As we shall discuss below, this protein is closely associated with Parkinson’s.

PARKIN Protein. Source: Wikipedia

PARKIN Protein. Source: Wikipedia

In human DNA, you have two copies of PRKN (also known as the PARKIN gene) – one from your mother, and one from your father. If you have two normal versions of the PRKN gene, it is referred to as a wild-type situation. If you have a genetic variation in one of these copies, it is referred to as a heterozygous variant – from the Greek words heteros meaning “the other (of two), and zygotos meaning “to couple or attach with or to a yoke”. If both copies carry the same genetic variation, this would be considered homozygous variant (the Greek homo meaning “same”).

Types of genetic variation. Source: mdpi

Types of genetic variation. Source: mdpi

And what does “exon 7 deletion” mean?

The regions of DNA that provide the instructions for making proteins are called genes. Copies of these regions are made, which are called RNA. These RNA copies, however, are not really exact copies of the DNA, because DNA contain introns and exons. An exon is a region of DNA that ends up within the final RNA copy, while an intron is a region of DNA that is cut out of the RNA copy.

When an RNA copy is first made, it is an exact copy of the DNA template, and this is referred to as a pre-RNA. This pre-RNA is then cleaned up and part of that process (called “splicing“) involves cutting out all of the introns. Thus, only the exons are left behind in the mature RNA. As a result, you don’t really want any variants in or deletions of the exons in a particular gene.

Source: Khanacademy

Source: Khanacademy

There are an average of 8.8 exons and 7.8 introns per human gene. PRKN contains 12 exons separated by large intron regions. When splicing has taken place, these exon regions of PRKN stick together like lego providing the instructions for making a PARKIN protein, like this:

Source: ResearchGate

Source: ResearchGate

If you look at the top row of the image above, you will see exon 7 is right in the middle and errors in (or deletion of) this exon result in an incorrect form of the PARKIN protein.

Which is bad right?

Yes, but you will remember that humans have two copies of PRKN and in the heterozygous cases, there is still a normal copy of PRKN providing a normal version of the PARKIN protein. So a person affected by a heterozygous PRKN variant still has a supply of PARKIN protein to do what it has to do.

Ok, so what does the PARKIN protein actually do?

The PARKIN protein appears to have different functions inside of cells, but it has been most thoroughly studied in the context of mitophagy.

What is mitophagy?

Mitophagy involves the disposal of old or dysfunctional mitochondria.

Mitochondria – you may recall from previous SoPD posts – are the power stations of each cell. They help to keep the lights on. Without them, the party is over and the cell dies.

Mitochondria and their location in the cell. Source: NCBI

You may also remember from high school biology class that mitochondria are tiny bean-shaped objects within the cell. They convert nutrients from food into Adenosine Triphosphate (or ATP). ATP is the fuel that cells run on. Given their critical role in energy supply, mitochondria are plentiful (some cells have thousands) and highly organised within the cell, being moved around to wherever they are needed.

Like you, me and all other things in life, however, mitochondria have a use-by date.

As mitochondria get old and worn out (or damaged) with time, the cell will dispose of them via the process of mitophagy.

What does PARKIN do in mitophagy?

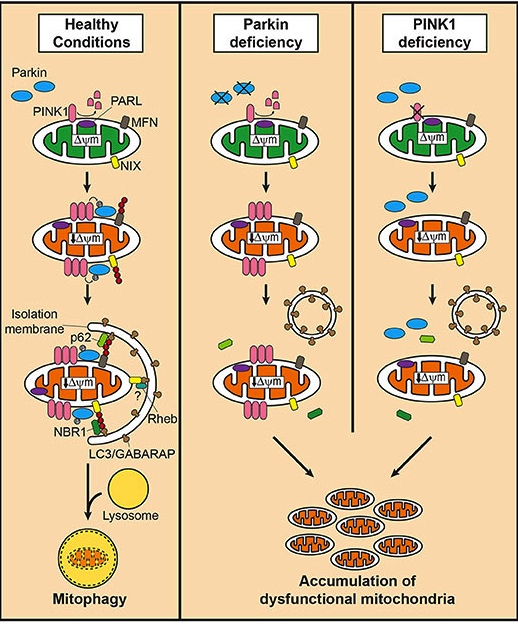

In mitophagy, PARKIN interacts with another Parkinson’s associated protein called PINK1. Like PARKIN, genetic variations in the PINK1 gene are also associated with early onset Parkinson’s.

In the process of mitophagy, these two protein play important functions.

PINK1 acts like a kind of handle on the surface of mitochondria. In normal, healthy cells, the PINK1 protein attaches to the surface of mitochondria and it is slowly absorbed until it completely disappears from the surface and is degraded. In unhealthy cells, however, this process is inhibited and PINK1 starts to accumulate on the outer surface of the mitochondria. Lots of handles poking out of the surface of the mitochondria.

Now, if PINK1 is a handle, then PARKIN is a flag that likes to hold onto the PINK1 handle. While exposed on the surface of mitochondria PINK1 starts grabbing the PARKIN protein. This pairing is a signal to the cell that this particular mitochondrion (singular) is not healthy and needs to be removed. The pairing start the process that leads to the development of the phagophore and eventually mitophagy.

Pink1 and Parkin in normal (right) and unhealthy (left) situations. Source: Hindawi

In the absence of normal PINK1 or PARKIN proteins, there is no handle-flag system and old/damaged mitochondria start to pile up. They are not disposed of appropriately and as a result the cell gets sick and ultimately dies.

Mitophagy. Source: Frontiersin

Mitophagy. Source: Frontiersin

As I said above, people with particular mutations in the PINK1 or PARKIN genes are vulnerable to developing an early onset form of Parkinson’s. It is believed that the dysfunctional disposal of (and accumulation of) old mitochondria are part of the reason why these individuals develop the condition at such an early age.

I see. So back to the research report. You said the researchers collected blood from 20 people with or without a heterozygous PRKN exon 7 deletion. What did they do with them?

They took the blood samples from 11 were carriers of a heterozygous PRKN exon 7 deletion and 9 were unaffected controls. From these blood samples, the investigators extracted some cells and converted them into stem cells using a trick of modern molecular biology (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this process). They then converted the stem cells into dopamine neurons and lymphoblasts (an immature white blood cell that can give rise to a type of immune cell known as a lymphocyte).

Given the role PARKIN plays in mitochondrial function, the researchers first ran a series of tests assessing how healthy the mitochondria were in these cells.

In the lymphoblast cells with the PRKN deletion, the researchers observed enhanced mitochondrial activity, suggesting increased ATP production. This increase in mitochondrial activity, however, was matched by an elevation in reactive oxidative species (which could cause oxidative stress – click here to read a previous SoPD post on oxidative stress).

When the researchers turned their attention to the dopamine neurons, they also included cells from a Parkinson’s patient who carried a PRKN genetic variant in their analysis and here they also saw an increase in reactive oxidative species, which was slightly more exaggerated in the cells from the PD patient carrying the PRKN variant:

Increase in ROS (labelled in red) in cells of different genetic backgrounds. Source: PMC

Increase in ROS (labelled in red) in cells of different genetic backgrounds. Source: PMC

While not significantly different from the non-manifesting PRKN variant carrier cells, this research suggests that there could be some biomarkers that could be used to differentiate variant carriers pre- and post-diagnosis – providing a system for measuring risk of developing the condition perhaps.

Curiously, the investigators also observed alterations in the membrane activity of mitochondria in PRKN genetic variant carriers, but a morphological analysis of the mitochondrial networks (groups of mitochondria functioning in the same area of a cell) were not significantly different.

So the researchers identified some molecular characteristics that might be used to monitor non-manifesting PRKN genetic variant carriers?

Exactly.

But in addition to the genetic variations in a single gene or region of DNA, there is the rest of one’s DNA that we also need to consider.

What do you mean?

Well, rather that simply focusing on a single genetic variation, we need to consider an individual’s polygenic risk score.

What does “polygenic risk score” mean?

A polygenic risk score is an estimate of an individual’s genetic risk of a particular disease, based on the combination of different versions of many genes (as opposed to just one) that are related to that disease. So instead of focusing on just one genetic risk factor (such as variants in the PRKN gene), a polygenic risk score represents the total number of genetic variants an individual has that increase their risk of developing a particular disease. Thus someone with two or three genetic variants may have a higher polygenic risk score than someone with just one genetic variant.

Source: CDC

Source: CDC

Polygenic risk scores for a particular disease are different for different people. And this is demonstrated in the image above. Each circle represents a person, and the higher the polygenic risk scores (red) are more likely to get the disease and those with lower scores (yellow) are less likely to get the disease. Most people will fall somewhere in the middle (yellow/orange) for most diseases, but each of us may (unknowing) have a higher polygenic risk score for a specific disease.

And polygenic risk scores make assessments of penetrance even more complicated, because we are now no longer dealing with just one genetic risk factor but rather the sum effect of a lot of minor genetic risk factors.

And recently, researchers explored how polygenic risk scores can influence risk in carriers of GBA1 genetic variants:

Title: Polygenic Parkinson’s Disease Genetic Risk Score as Risk Modifier of Parkinsonism in Gaucher Disease.

Title: Polygenic Parkinson’s Disease Genetic Risk Score as Risk Modifier of Parkinsonism in Gaucher Disease.

Authors: Blauwendraat C, Tayebi N, Woo EG, Lopez G, Fierro L, Toffoli M, Limbachiya N, Hughes D, Pitz V, Patel D, Vitale D, Koretsky MJ, Hernandez D, Real R, Alcalay RN, Nalls MA, Morris HR, Schapira AHV, Balwani M, Sidransky E.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2023 May;38(5):899-903.

PMID: 36869417 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers analysed the DNA of 225 patients with Gaucher disease (a metabolic condition associated with GBA1 genetic variants – click here to read an old SoPD post that discusses Gaucher disease). Within this population of 225 people there were 199 without Parkinson’s and 26 who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s (individuals with Gaucher’s have a high incidence of Parkinson’s).

When the investigators looked at the DNA of all of these individuals, they found that, on average, the individuals with Gauchers and Parkinson’s had a significantly higher Parkinson’s polygenic risk score than those Gaucher individuals without PD. These results suggest that a higher polygenic risk score could be a risk modifier for developing Parkinson’s in individuals who carry a particular genetic risk factor for the condition.

You are hopefully starting to see why the genetics of Parkinson’s is really difficult to study.

So what does it all mean?

I am aware of an elderly lady who carries not one, but two genetic risk factors for developing Parkinson’s. She is in her mid 80s and after a long life, she is yet to show any signs of the disease – no tremor, no rigidity, no slowness of movement. The genetics of Parkinson’s remains a real mystery, but here is what we do know: While there are genetic variations that can increase one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s, the condition can not be considered a genetic disease (in the same way Huntington’s disease is).

It is likely that in addition to one’s polygenic risk score, environmental features and life events may also play a role (click here to read a previous SoPD post about the Gernsheimer twins who share identical genetics (including a GBA1 variant), but only one has been diagnosed with PD). Life style choices could also be involved – too little exercise may increase the risk associated with some genetic risk factors. But two important takeaways from this post should be 1.) the penetrance of most Parkinson’s-associated genetic risk factors is in many cases low, and 2.) other genetic and environmental details probably play an important determinant of whether a variant is likely to result in a diagnosis of Parkinson’s.

Hopefully ongoing research into the genetics of Parkinson’s and biomarkers associated with the related biology will help to identify and monitor individuals who could be at risk of developing the condition. The insights gained from this work will hopefully help reduce the incidence of Parkinson’s in future generations and aid in earlier interventions.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Reddit