|

# # # # Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative condition that is diagnosed and monitored based on clinical observations and scoring systems – both of which are not perfect and subjective. Biomarkers (a biological molecule found in bodily fluids or tissues that is an indicator of a normal or abnormal processes) represent an important development for medicine as they provide assurance and quantitative measures of disease, aiding the diagnostic and treatment process. Recently there has been a lot of new research highlighting possible biomarkers for Parkinson’s, including proteins associated with the synthesis of dopamine (a chemical which is severely reduced in the brains of people with Parkinson’s). In today’s post, we will discuss what a biomarker is and review some new research on a potential biomarker for ‘Lewy body disease’. # # # # |

The search for biomarkers. Source: NIH

2023 is quickly becoming the year of potential biomarkers for Parkinson’s. There has been a lot of new research in this space.

For example, earlier this year, the Michael J Fox Foundation and collaborators reported new data regarding the alpha synuclein seeding assay (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic).

Tests that can clearly define and track medical conditions over time are critical to developing better treatments and would certainly be invaluable in Parkinson’s research.

And this week we saw researchers publish further data, highlighting another potential biomarker.

What did they report?

This is the report:

Title: DOPA decarboxylase is an emerging biomarker for Parkinsonian disorders including preclinical Lewy body disease.

Title: DOPA decarboxylase is an emerging biomarker for Parkinsonian disorders including preclinical Lewy body disease.

Authors: Pereira JB, Kumar A, Hall S, Palmqvist S, Stomrud E, Bali D, Parchi P, Mattsson-Carlgren N, Janelidze S, Hansson O.

Journal: Nat Aging. 2023 Sep 18. Online ahead of print.

PMID: 37723208 (The report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators analysed the concentrations of the 2,943 proteins in cerebrospinal fluid samples that were collected from 81 people with ‘Lewy body disease’, (including 48 cases of Parkinson’s and 33 with dementia with Lewy bodies) and they compared those results from samples collected from 347 controls from the Swedish BioFINDER 2 cohort.

What do you mean by “Lewy body disease”?

The researchers pooled all of the samples from Parkinson’s and dementia with Lewy bodies cases into a large group as a first starting point. So Lewy body diseases here simply refers to diseases associated with Lewy body pathology (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on Lewy body pathology and click here to read a previous SoPD post on dementia with Lewy bodies).

Ok, got it. And remind me again: what is cerebrospinal fluid?

Cerebrospinal fluid is the liquid our brain and spinal cord sits in. It can be sampled via a procedure called a lumbar puncture (LP). An LP is performed by inserting a tiny needle between the vertebrae at the bottom of the spinal cord and a small sample of cerebrospinal fluid can be taken.

Lumbar puncture. Source: InformedHealth

Lumbar puncture. Source: InformedHealth

Cerebrospinal fluid is an accessible liquid sample that is directly exposed to the brain.

So what did they find?

When they compared the samples from Lewy body diseases and controls, 10 proteins were found to be significantly elevated and four were reduced in the Lewy body diseases samples. Of the elevated proteins, the #1 result was an enzyme called DOPA decarboxylase.

What is DOPA decarboxylase?

DOPA decarboxylase (also known as DDC, Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, or AADC) is the enzyme involved in the production of the chemical dopamine. Specifically, DOPA decarboxylase converts the chemical levodopa into dopamine.

Levodopa is naturally produced in the brain from a protein called tyrosine which is absorbed into brain cells from the blood. Tyrosine is converted into levodopa by an enzyme called tyrosine hydroxylase. Levodopa is also the basis of many treatments for Parkinson’s (such commercial versions of Levodopa include ‘Sinemet’).

The production of dopamine. Source: Slideplayer

So DOPA decarboxylase helps to turn levodopa into dopamine. But why is dopamine important?

Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that helps us to move freely. Without it, our movements become inhibited – as in the case of Parkinson’s.

The majority of the dopamine produced in your brain is made in a region called the substantia nigra, deep inside you brain. These dopamine producing cells also generate another chemical called neuromelanin, which has a dark colouration to it – making it visible to the naked eye. As you can see in the image below, the substantia nigra region is easy to see on the section of healthy control brain on the left, but less visible on the section of brain from a person who passed away with Parkinson’s.

The dark pigmented dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source:Memorangapp

The dark pigmented dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source:Memorangapp

The dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra release their dopamine in different areas of the brain. The primary regions of that release are areas of the brain called the putamen and the Caudate nucleus. The dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra have long branches/projections (called axons) that extend a across the brain to the putamen and caudate nucleus, so that dopamine can be released there.

The projections of the substantia nigra dopamine neurons. Source: MyBrainNotes

In Parkinson’s, these ‘axon’ extensions that project to the putamen and caudate nucleus gradually disappear as the dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra are lost. When one looks at brain sections of the putamen after the axons have been labelled with a dark staining technique, this reduction in axons is very apparent over time, especially when compared to a healthy control brain (PLEASE NOTE: The image provided below is an example and may not apply to everyone – people progress at different rates in Parkinson’s).

The putamen in Parkinson’s (across time). Source: Brain

The putamen in Parkinson’s (across time). Source: Brain

So the researchers found that DOPA decarboxylase was the highest elevated protein in the Lewy body disease samples. What did they do next?

Well, given that levodopa is the most commonly used medication for the treatment of Parkinson’s, the researchers repeated their analyses on samples from 45 cases of recently diagnosed Lewy body disease who had not yet started any dopaminergic medications. The results of this analysis confirmed that DOPA decarboxylase was the most elevated protein.

Within the Lewy body disease group, did the researchers see any difference between people with Parkinson’s vs people with dementia with Lewy bodies?

No, they saw no difference.

Do they know if DOPA decarboxylase can detect Lewy body disease before it is diagnosed?

They look at this by using the control samples and testing them in the alpha synuclein seeding assay – this is a test for detecting aggregation prone alpha synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid (Click here to read a recent SoPD post on this topic).

They found 35 cases in the control group had positive tests for the alpha synuclein seeding assay, and they compared these to 310 controls that gave negative results. Interestingly, while the researchers did not see any significant differences in clinical motor scores in these control cases, in the alpha synuclein seeding assay positive controls there was already a significantly increase in DOPA decarboxylase levels.

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

Of the 35 cases in the control group had positive tests in the alpha synuclein seeding assay, 12 individuals went on to be diagnosed with clinical Lewy body disease within 2.5 years. None of the negative control group developed Lewy body disease.

This result suggests that elevated levels of DOPA decarboxylase could be a potential biomarker for detecting Lewy body disease before it is even diagnosed, which could have important relevance for clinical trials exploring early intervention therapies.

Very interesting. Do we know if DOPA decarboxylase levels can be used to assess progression in individuals already diagnosed?

Great question, and the investigators did have a look at this. Using longitudinal clinical data from the 81 individuals with Lewy body disease, the researchers found that elevated levels of DOPA decarboxylase were associated with worse global cognition, low memory performance, worse cognitive speed and visuospatial abilities. Curiously, there was “no significant relation with motor symptoms”. This finding suggests DOPA decarboxylase could have clinical value when assessing cognitive dysfunction specifically.

To further assess the potential utility of DOPA decarboxylase as a biomarker, the researchers collected cerebrospinal fluid samples from 40 cases of atypical Parkinsonisms.

What is atypical Parkinsonisms?

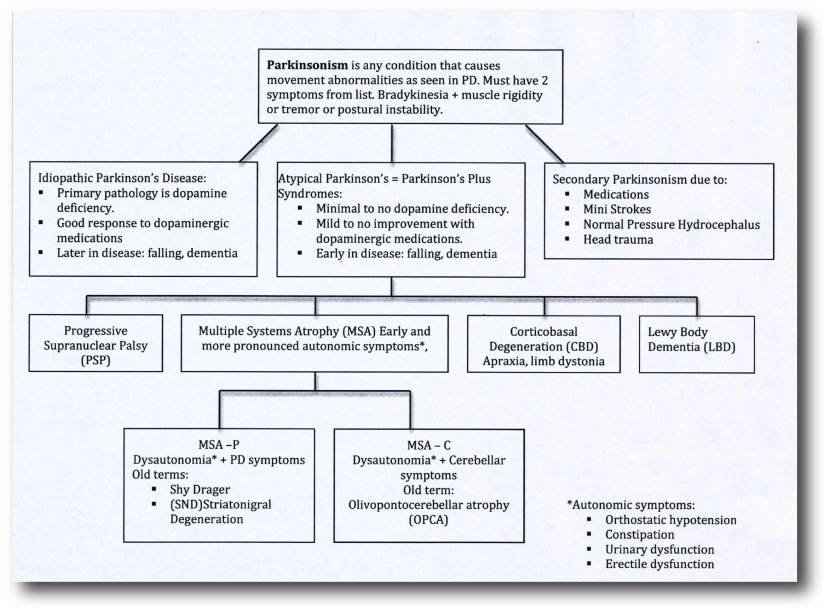

‘Parkinsonisms’ refer to a group of neurological conditions that cause movement features similar to those observed in classical ‘Parkinson’s disease’, such as tremors, slow movement and stiffness. But these other neurological conditions are considered atypical as they display subtle differences to Parkinson’s disease. The name ‘Parkinsonisms’ is often used as an umbrella term that covers Parkinson’s disease and all of the other ‘Parkinsonisms’.

Parkinsonisms are generally divided into three groups:

- Classical idiopathic Parkinson’s (the common spontaneous form of the condition)

- Atypical Parkinson’s or Parkinson-plus syndromes (such as Multiple System Atrophy (MSA – click here to read a previous SoPD post on MSA) and Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP))

- Secondary Parkinson’s (which can be brought on by mini strokes (aka Vascular Parkinson’s), drugs, head trauma, etc)

Source: Parkinsonspt

Source: Parkinsonspt

The researchers analysed cerebrospinal fluid samples from 11 MSA cases, 24 PSP cases, and 5 individuals with corticobasal syndrome (CBS), and found that DOPA decarboxylase was significantly elevated in these conditions as well. The investigators interpreted this finding by proposing that DOPA decarboxylase “might be a marker of dopaminergic dysfunction rather than α-synuclein-based Lewy body pathology” and that the alpha synuclein seeding assay in conjunction with DOPA decarboxylase “might be complementary biomarkers for the diagnosis and discrimination of LBD and atypical Parkinsonian disorders“.

Do they have to do a lumbar puncture to achieve these results? Or can they see similar outcomes with blood samples?

Another great question. The researchers did have a look at this. To do it, they repeated their experiment using blood samples collected from 64 individuals with Lewy body disease, 56 people with atypical Parkinsonism (30 MSA & 26 PSP cases) and 54 controls.

Like the cerebrospinal fluid findings, the researchers found that DOPA decarboxylase levels were significantly elevated in the blood samples of the Lewy body disease and atypical Parkinsonism cases compared to the controls (DOPA decarboxylase was unable to discriminate between Lewy body disease and atypical Parkinsonism):

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

Is this the first time anyone has ever explored DOPA decarboxylase as a potential biomarker?

No. In 2021, this report was published in which researchers noticed an increase in DOPA decarboxylase levels:

Title: Peripheral decarboxylase inhibitors paradoxically induce aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase.

Title: Peripheral decarboxylase inhibitors paradoxically induce aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase.

Authors: van Rumund A, Pavelka L, Esselink RAJ, Geurtz BPM, Wevers RA, Mollenhauer B, Krüger R, Bloem BR, Verbeek MM.

Journal: NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021 Mar 19;7(1):29.

PMID: 33741988 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers came to their findings from a very different angle to the research report reviewed above. Here the scientists were interested in exploring how the alterations in DOPA decarboxylase levels may contribute to the dosage of levodopa treatment required in patients with Parkinson’s. Given the variability in levodopa treatment between patients, they were curious to find out what was happening with DOPA decarboxylase levels in the body.

They collected blood samples from three independent cohorts of patients with Parkinson’s or atypical Parkinsonism (a total of 301 cases) and compared DOPA decarboxylase levels in those patients already on levodopa treatment (140 individuals) to the patients not yet on levodopa treatment (161 cases).

They found that DOPA decarboxylase activity was elevated in the group already using levodopa compared to the patients not being treated, and the individuals with the most elevated levels were older, had a longer disease duration, and also had a higher daily levodopa dose:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

The researchers in this study found their results “paradoxical“, because all of the individuals who are being treated with DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors (such as carbidopa and benserazide), which block the conversion of levadopa to dopamine outside the brain. These DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors can not access the brain, which leaves more levadopa to be converted into dopamine in the central nervous system where it is needed.

But if these DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors are floating around in the blood, why is there so much DOPA decarboxylase activity? The investigators wondered if this could partly explain the “increase the peaks and troughs in plasma levodopa levels contributing to the development of response fluctuations”.

It will be interesting to explore this further, but first we need to see if increased levels of DOPA decarboxylase are observed in other independent cohorts, and determine how useful this enzyme could be as a biomarker for Parkinson’s (or Lewy body disease).

So what does it all mean?

There is a critical need for good biomarkers in Parkinson’s research. Biological indicators that can help to better stratify and track patients over time are key to not only giving us a better understanding of the condition(s), but also in the efforts to find novel treatments that can help slow down progression. In today’s post, we have reviewed research hinting at the enzyme DOPA decarboxylase as a potential biomarker, and the scientists involved in the study have asked whether it and another assay might act as “complementary biomarkers for the diagnosis and discrimination” of Parkinson’s and other Lewy body diseases. Before taking that step, independent replication and validation of the finding is required and previous research (reviewed above) suggests that this might be challenging.

The fact that much of this biomarker research is having a hard time identifying biomarkers specific to “Parkinson’s” could bring into question our strategy of broadly grouping people with similar features/symptoms under single labels. Perhaps rather than identifying biomarkers that differentiate between people with and without “Parkinson’s”, there is a need for an analysis that focuses on just the “Parkinson’s” cohort and tries to split them up into smaller groupings. If such a method provides replicable results across independent cohorts, perhaps faster progress could be made.

It’s just a thought.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from verbeeldingskr8

6 thoughts on “DOPA de-car-box-yl-ase”