|

# # # # When considering the development of new drugs for Parkinson’s, it is often forgotten how much of a struggle it was to get levodopa – the current ‘gold standard’ treatment for Parkinson’s – approved for clinical use. After some initially very encouraging results (replicated by three independent labs), the agent struggled to move forward as the broader research community presented mixed and conflicting findings (including two randomised, double-blinded studies that showed no positive effects at all). Drug development is never a straightforward path. Rather it is a process of trial-and-error, with iterative steps in our understanding about the biology of diseases aiding us on the journey. In today’s post, we will look back at the roller-coaster ride that was the early development of levodopa as a therapy for Parkinson’s. # # # # |

Source: Alpha-Sense

Source: Alpha-Sense

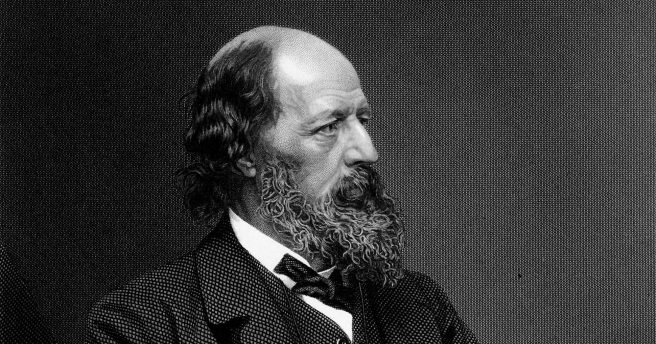

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers”

The development of a new treatment for any medical condition is hard.

Correction.

Let me rephrase that.

The development of a new treatment for any medical condition is EXTREEEEMELY hard.

We live in a wonderful age where anything seems medically possible. From the rapid development of vaccines for novel pandemic viral outbreaks to gene therapy treatments that are helping children with spinal muscular atrophy to walk, it is wonderous what can be achieved. It is an epoch in which we have built up a huge arsenal of medications that defend us against many of the pathogens of the world and help to treat the symptoms of a wide range of conditions. Some of these therapies have such remarkable biological properties that they are used in the treatment of more than one condition. And in this amazing reality, we have begun to develop treatments that don’t just deal with the symptoms of a condition, but stop the disease in its tracks.

Given this circumstance, it is all to easy to take for granted the long and arduous process that was required for each of those therapies to get to the point where they are being used in clinical settings. After the thousands of hours of preclinical research, the clinical trial process takes an additional extended period of time, and it is never a straight line. And in a world where western society has developed high expectations for immediate gratification, it is important to sometimes reflect on just how hard the development of novel therapies can be.

A good case study of the difficulties associated with drug development is the early clinical investigations into the use of levodopa for Parkinson’s.

It is considered the ‘gold standard’ treatment for Parkinson’s, with most of the affected population are taking some form of this agent during the course of their treatment. While other neurodegenerative conditions, like Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s disease, and motor neurons disease have very limited symptomatic treatment options, the Parkinson’s community is extremely lucky that levodopa is both available and efficacious.

And I say ‘lucky’ because in the early days of the clinical testing of levodopa, there were moments when this agent almost didn’t survive.

To fully appreciate that statement, we need to go back to the 1960’s.

Back to a time when there were basically no treatment options for Parkinson’s.

“Behold, we know not anything”

In November 1960, a Ukrainian/Austrian scientist named Oleh Hornykiewicz approached the neurologist Walther Birkmayer with an intriguing idea. Following a series of investigations into postmortem brains, Hornykiewicz had determined that there were severe reductions in the levels of a chemical called dopamine in the brains of people with Parkinson’s. He wondered if treating these individuals with a naturally occurring amino acid called ‘levodopa‘ (also known as L-dopa) might help rescue this reduction of dopamine.

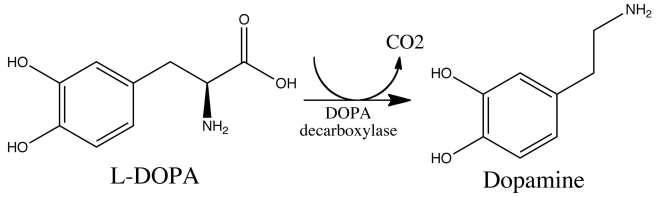

Dopamine had recently been discovered to be a neurotransmitter, by the Swedish researcher Avid Carlsson. A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger that passes between neurons to share information. Hornykiewicz was thinking that with less dopamine in the brain, the neurons involved in movement could not communicate with each other and this was causing the motor symptoms associated with the condition.. Levodopa is the main ingredient in the production of dopamine and in the brain it is quickly converted – by an enzyme called DOPA decarboxylase – to dopamine:

The chemical conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine. Source: Nootrobox

The chemical conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine. Source: Nootrobox

Hornykiewicz questioned if the remaining dopamine neurons and other cells in the brain might be able to absorb the administered levodopa and convert it to dopamine in the absence of the dopamine neurons that had been lost in Parkinson’s, and maybe this could help correct the motor symptoms of the condition. And this was the idea he put to Walther Birkmayer in 1960.

He was proposing a short clinical study involving the intravenous delivery of up to 150 mg levodopa. Birkmayer was at the time the head of the neurology ward at the largest “Home-for-the-Aged” in Vienna, and had a large population of permanently housed Parkinson’s patients. He also had a great deal of clinical experience with the condition, and he was not very enthusiastic about the proposed study. After some persuasion, however, Birkmayer ultimately agreed to the project and in July 1961, they injected the first patients with levodopa.

Hornykiewicz (left) & Birkmayer (right). Source: Wiley

Hornykiewicz (left) & Birkmayer (right). Source: Wiley

What happened next, Birkmayer later described as the “Levodopa miracle”.

In their report, he and Hornykiewicz wrote: “The effect of a single intravenous administration of levodopa, was, in short, a complete abolition or substantial relief of akinesia. Bed-ridden patients who were unable to sit up; patients who could not stand up when seated; and patients who, when standing could not start walking, performed after L-DOPA all these activities with ease. They walked around with normal associated movements and they even could run and jump. The voiceless, aphonic speech, blurred by pallilalia and unclear articulation, became forceful and clear as in a normal person. For short periods of time the patients were able to perform motor activities which could not be prompted to any comparable degree by any known drug” (Source).

It must have been truly wonderous.

Similar to the scenes that played out in the movie ‘Awakenings’, which tells the story of Oliver Sacks’s 1969 experiments with levodopa in catatonic patients who survived the 1919–1930 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica.

Awakenings. Source: Oliversacks

Awakenings. Source: Oliversacks

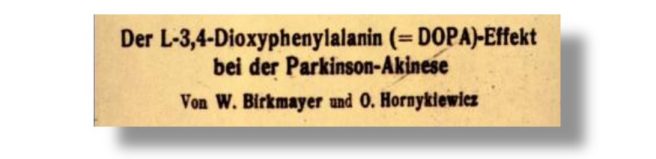

Over the next few months, Hornykiewicz and Birkmayer tested levodopa in 20 Parkinson’s patients, and then wrote up their results. In their report, they noted that “the drug worked from the first dose, and its beneficial action from bradykinesia was reported to last from 3 to 24 hours. Pretreatment with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor isocarboxazid, considerably prolonged the anti-akinetic effect” (Source). They submitted their manuscript to the official Journal of Vienna’s Medical Society (“Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift”) and it was published in November 1961:

Title: [The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia].

Title: [The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia].

Authors: Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O.

Journal: Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1961 Nov 10;73:787-8.

PMID: 13869404

In October 1961, Hornykiewicz and Birkmayer travelled to Basel (Switzerland) to meet with scientists at at Hoffman-LaRoche (now just Roche), to share their findings and request more levodopa for further trials. The company’s researchers were intrigued, but one of the marketing experts suggested that the Parkinson’s market “was far too small to justify the risks of going into the business of commercializing a non-patentable substance such as levodopa” (Source). Regardless, Hornykiewicz and Birkmayer returned to Vienna with additional levodopa to continue their studies.

Curiously, at the same time as Hornykiewicz and Birkmayer were conducting their study in Vienna, Ted Sourkes and Gerald Murphy in Montreal were asking the neurologist André Barbeau to give levodopa orally (100–200 mg) to a small group of Parkinson’s patients.

Ted Sourkes. Source: Theglobeandmail

Ted Sourkes. Source: Theglobeandmail

In the report that they published in 1962, they wrote that “In all cases with Parkinson’s disease, levodopa ameliorated the rigidity, especially when combined with an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase” (Source). And then just one year later, (independent of Hornykiewicz and Birkmayer) Franz Gerstenbrand and Kurt Patejsky of Vienna’s University Department of Neurology and Psychiatry published equally encouraging results with levodopa in Parkinson’s patients (Source).

Now, readers will be forgiven for thinking that, following this amazing triad of independent replications of the same result, levodopa immediately took on the mantle of the ‘gold standard’ treatment for Parkinson’s.

Because it didn’t.

What happened next will appear very strange to observers from outside of the medical research field, but it is a regular phenomenon to those inside.

“O let the solid ground; Not fail beneath my feet; Before my life has found; What some have found so sweet”

News of these initial pilot studies was met with a mixture of intrigue and skepticism from the medical community (“How can such a simple chemical…?”). By their very nature, good scientists question everything. They also like to try and replicate the results themselves. And this is exactly what Patrick McGeer in British Columbia did. He and his collaborator Ludmila “Lola” Zeldowicz recruited 10 participants into a study – six with established Parkinson’s (4 to 11 years since diagnosis), three were postencephalitic Parkinsonism (7 to 39 years), and the final participant had arteriosclerotic Parkinsonism (8 years). McGeer and Zeldowicz were the first to test oral levodopa and it was administered as 250mg pills, with daily doses ranging between 1 to 5mg for a few days and in one case out to 2 years. Intravenous levodopa was also assessed in the study, up to 500mg/day: Title: Administration of Dihydroxyphenylalanine to Parkinsonian patients.

Title: Administration of Dihydroxyphenylalanine to Parkinsonian patients.

Authors: McGeer PL, Zeldowicz LR.

Journal: Can Med Assoc J. 1964 Feb 15;90(7):463-6.

PMID: 14120951 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

But during the study, only two of the participants showed any improvement in their Parkinsons symptoms (and one of those was on the placebo treatment). The investigators stated that the “improvements were not striking” and they concluded that levodopa “has little to offer as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of Parkinsonism“.

Following McGreer & Zeldowicz , there were other studies with mixed results, including two independent double-blind clinical studies that also did not show any therapeutic benefit following 1.5 mg/kg of intravenous levodopa (Source & Source). In cases where some signs of improvements were observed, they were short lived.

In his critical review of the first nine years of clinically testing levodopa, André Barbeau provided the following table to highlight just how mixed the results were across the various published studies:

Note that all of the studies except Fehling (1966) and Rinne (1968) were open label. Source: PMC

The situation became more confused when Birkmayer and Hornykiewicz attempted to replicate their findings in a larger study of 200 individuals with Parkinson’s and they didn’t see the same positive outcomes of their earlier studies. They administered levodopa once or twice weekly together with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Only 20% of the participants showed any improvement in their motor symptoms, while half of the participant displayed an improvement in other clinical symptoms (such as impaired speech or posture), and the remaining 30% were judged to experience no improvements at all (Source). Many commentators at the time concluded that the observed improvements were probably due to the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

At a symposium in 1965, Hornykiewicz admitted that the place for levodopa as a treatment for Parkinson’s was unclear due to the mixed results and its side effects (which were significant – such as nausea and vomiting). Further still, in his 1965 review of the treatment of Parkinson’s, neurologist Roger Duvoisin wrote that “despite enthusiastic claims of therapeutic benefit, no evidence has been presented that DOPA effects are in any way specific” (Source). Duvoisin concluded that levodopa had “only an occasional and transient effect” and was “clinically impractical“.

Clinically impractical.

So the question then becomes how on Earth did levodopa come to be the effective treatment we now have for Parkinson’s?

As we said above, the road to success in drug development is never a straight line.

“It’s better to have tried and failed than to live life wondering what would’ve happened if I had tried”

Enter George Cotzias, a Harvard Medical School graduate working at Brookhaven National Laboratory, in Long Island, New York.

George Cotzias. Source: Parkinsonseurope

In 1966, George started conducting experiments with oral levodopa in people with Parkinson’s, but he later admitted that his initial reasons for doing so were mistaken:

”We were led to the erroneous but fruitful hypothesis that the brain (another ectodermal organ) must be further depleted of melanin precursors (which are also catechol precursors) by their sequestration in the skin. We therefore administered melanin and catecholamine precursors, which, after trial and error, led to the use of levodopa

for the treatment of parkinsonism” (Source)

In trying to “re-pigment” the brain, George gave levodopa at small doses given every 2 hours and gradually increased this up over a period of weeks. This protocol had remarkably positive results on the patients’ motor symptoms for a long duration. Cotzias and colleagues published their results in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1967:

Title: Aromatic amino acids and modification of parkinsonism.

Title: Aromatic amino acids and modification of parkinsonism.

Authors: Cotzias GC, Van Woert MH, Schiffer LM.

Journal: N Engl J Med. 1967 Feb 16;276(7):374-9.

PMID: 5334614

The ultimate doses being used by Cotzias and his team were very high (in some cases doses of up to 16 grams per day), and as a result, the researchers were the first to report the development of uncontrolled, involuntary movements (known as dyskinesia). They discussed this in a second New England Journal of Medicine report published in 1969:

Title: Modification of Parkinsonism – chronic treatment with L-dopa.

Title: Modification of Parkinsonism – chronic treatment with L-dopa.

Authors: Cotzias GC, Papavasiliou PS, Gellene R.

Journal: New England Journal of Medicine. 1969 Feb 13;280(7):337-45.

PMID: 4178641

There were a lot of technical tweaks in these studies that differentiated them from the earlier studies with mixed results. For example, Cotzias and colleagues realised the need to use pure L-dopa (rather than other mixed versions that included inactive ingredients such as D-dopa. D,L-dopa had been used in many of the early studies). They also used smaller capsules which allowed them to use lower and more frequent doses.

For those interested, the Movement Disorder Society has some video interviews of George Cotzias (Click here and here to watch them), but note his first words:

“For any development of any kind of medicine, a lot of things proceed the development, but the development is never final, a lot of things have to come after”

Now, readers will be forgiven for thinking that, following the positive developments from Cotzias and his team, levodopa immediately took on the mantle of the ‘gold standard’ treatment for Parkinson’s (deja vu?). Again the medical community did not immediately recognize the significance of the findings. In fact, Melvin Yahr and Roger Duvoisin – well respected experts in the Parkinson’s research field – wrote in 1968, “Cotzias et al., (1967) have reported oral administration of L dopa in dosages of up to 16 grams per day. However, there has also been an appreciable incidence of undesirable side effects. Though undoubtedly at this dosage a sustained effect can be obtained, the role of dopa is far from established.” (Source)

“Come, my friends, Tis not too late to seek a newer world”

One of the truly crucial steps in the early development of levodopa as a treatment for Parkinson’s came from researchers at Hoffman-LaRoche in Basel.

They had created an interesting molecule called Ro 4-4602 that was giving them strange results which they said “could not be explained“.

Ro 4-4602 was a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor.

You will remember from our discussion above that DOPA decarboxylase is the enzyme that converts levodopa to dopamine. By inhibiting DOPA decarboxylase, the researchers at Hoffman-LaRoche had expected that Ro 4-4602 would reduce dopamine levels when they injected it into the body.

And it did.

Everywhere.

Except in the brain.

And rather than going down, brain levels of dopamine actually increased after Ro 4-4602 was injected into the blood stream.

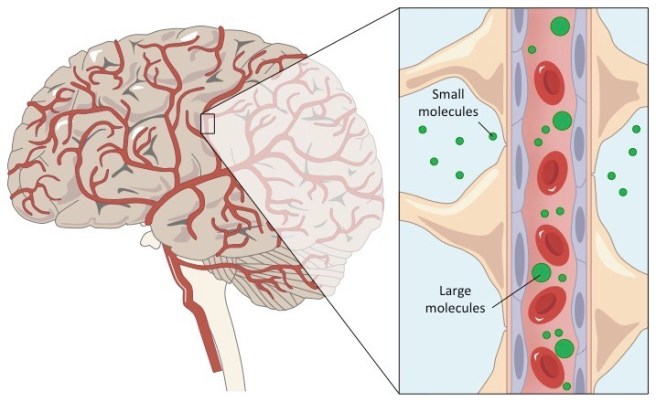

There was a bit of head scratching about this result, but they eventually realised that the effect was occurring because Ro 4-4602 could not cross the blood brain barrier.

The blood-brain-barrier. Source: Bioninja

The blood-brain-barrier. Source: Bioninja

The blood brain barrier is a the protective layer that surrounds the brain. It limits the types of chemicals and drugs that can access the central nervous system. Many small molecules can get in, but larger molecules cannot. Dopamine is an example of a chemical that cannot cross the blood brain barrier, while levodopa is a molecule that can. Usually, the blood brain barrier is a major impediment in drug development as there are lots of potentially useful agents that cannot cross it. But in the case of Ro 4-4602, the blood brain barrier represented a strategic advantage.

The researchers at Hoffman-LaRoche realised that they could inhibit the DOPA decarboxylase enzyme everywhere else in the body, but leave it active in the brain. In this fashion, when levodopa is administered (either orally or intravenously) it could travel around the body without being converted to dopamine and only when it entered the brain would it be changed into the much needed dopamine.

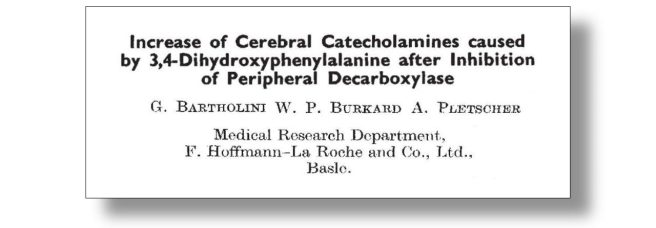

The researchers conducted a series of experiments and found that indeed Ro 4-4602 increased dopamine levels in the brain, and they concluded that use of DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors “may have a beneficial effect in neurological disorders such as Parkinsonism“:

Title: Increase of cerebral catecholamines caused by 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine after inhibition of peripheral decarboxylase.

Title: Increase of cerebral catecholamines caused by 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine after inhibition of peripheral decarboxylase.

Authors: Bartholini G, Burkard WP, Pletscher A.

Journal: Nature. 1967 Aug 19;215(5103):852-3.

PMID: 6049735

Without DOPA decarboxylase inhibition, very little of the levodopa that was being administered to people with Parkinson’s was actually getting to the brain. Instead it was being converted into dopamine in areas like the gut (which caused people to feel nausea and to vomit) and in the blood stream (where it could lead to issues with the heart). This is probably why so many of the early clinical studies with levodopa gave such mixed results and required very high doses of levodopa to be effective.

In 1968, George Cotzias and colleagues began to experiment with a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor called alpha-methyldopahydrazine (later known as carbidopa – maybe you have heard of this?). Their results demonstrated that the combination of levodopa with alpha-methyldopahydrazine allowed for less levodopa to be required for controlling Parkinson’s symptoms, a more rapid induction of the beneficial effects, and significant reductions in side effects (such as nausea and cardiovascular issues – Source).

In 1970, the US Food and Drug Administration approved levodopa for the treatment for Parkinson’s. But it should be noted that this was just approval for levodopa by itself (following a study by Melvin Yahr and collaborators assessing levodopa in 56 Parkinson’s patients over a year; 49 of the participants showed considerable improvements – Source). It would take another five years before the combination of levodopa and carbidopa was approved (in 1975). That new combination drug was named Sinemet (derived from the Latin ‘sine’, meaning without, and ’emesis’, meaning vomiting – a common side effect of levodopa by itself).

So 14 years passed between the initial pilot studies and a clinically viable product being broadly introduced.

And it wasn’t until 1975 that researchers finally had proof of what levodopa was doing in the brains of people with Parkinson’s. Hornykiewicz and collaborators reported on analyses that they had made on postmortem brain tissue from levodopa-treated and untreated Parkinson’s patients, and they clearly demonstrated that the benefits of levodopa were associated with its conversion to dopamine in the brain (Source). Levels of dopamine in the brain (specifically regions called the putamen and caudate nucleus) were 9 – 15 times higher in levodopa treated Parkinson’s patients when compared to the untreated individuals.

And as George Cotzias said in this interview mentioned above “the development is never final, a lot of things have to come after” – there have been many refinements made to levodopa therapy over the years. Each iteration has taken time and effort to sculpt and bring to clinical use. Each has run into unforeseen hurdles and barriers that needed to be overcome. Each has required new learning and insights. They have included different delivery systems, such as inhalable levodopa (Inbrija) and continuous delivery produodopa. They have also included alternative combinations – such as levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone – to further boost available dopamine reserves. But the “development is never final”.

Inhalable levodopa – Inbrija. Source: Brandsymbol

Inhalable levodopa – Inbrija. Source: Brandsymbol

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new”

So what can be learned from the development of levodopa as a therapy for Parkinson’s?

In the discussion section of their wonderful “Four pioneers of L-dopa treatment” (which has been useful source material for much of this post), Andrew Lees, any of the early studies were performed using low doses of levodopa, short periods of treatment, and involved the D,L-dopa formulation rather than the more effective L-dopa version of levodopa.

They also questioned if diagnosis might have played a role in some of the individual responses. In the 1960’s, we did not differentiate between different forms of atypical Parkinson’s and the methods of diagnosis have changed over time. So there may have been some individuals involved in the early studies who simply wouldn’t have responded to levodopa (even today’s versions of it).

Lees et al did not write enough about the importance of the introduction of DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors into the story of levodopa. Maybe it was considered inevitable that this case of drugs would come into play in order to boost dopamine levels in the brain, but this adaptation seems critical to the success of the therapeutic overall. The ‘adaptation’ being a shift from a monotherapy to a combination approach (hmm, funny that).

In their celebration of the contributions of Arvid Carlsson, Oleh Hornykiewicz, George Cotzias, and Melvin Yahr, Lees et al mention a lot of other researchers and this is another important aspect of drug development: it takes a village. The process involves a lot of people striving to understand and make the world a better place. The big discoveries often overshadow the tiny insights that help to keep the wheels moving and push the field forward.

And the process is very human. Sometimes the scientists involved start with admittedly erroneous hypotheses (famously George Cotzias), but they are dedicated and keen-eyed enough to know when they need to change tack in order for pieces of the puzzle to come together. It should also be noted that the failures often upset the researchers more than the patients. Many of scientists have completely invested themselves in their research and despite their better judgement, they let a part of themselves believe that they are on to the next big discovery. When it doesn’t play out the way one might have hoped, it can take a terrible toll on them.

As I wrote above, drug development is never a straightforward path. Clinical trials rarely go according to plan and often don’t give us the results we hoped for, which helps to show us how little we actually know. But it should also be appreciated that the development of new therapies is never a finished story, and habits should be formed around always returning to the drawing board to see what can be corrected or improved upon. Reading on the development of levodopa for this post has been sobering. For so long has it been the staple treatment, one takes it for granted and gives little thought to the struggles the early researchers faced. The challenges in getting it to the point of regulatory approval and into clinical use were considerable and they should be appreciated as we now try to bring new and significantly more complicated therapies forward.

“It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven;

that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”

(Tennyson was only 24 when he wrote these words, and there was so much more to come)

For Tom (F, not I) and his team

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from poetryfoundation.

My life partner was diagnosed with Parkinson’s a mere 30 years after carbidopa/levodopa was developed. Our lives would have been completely different without it–she might not even be alive.

This story thus has great significance for us. There is nothing inevitable about progress of this kind. It is full of long shots and dead ends. But the times when it pays off can mean everything to patients affected by an illness.

Indeed it is interesting that the solution here turned out to be a dual therapy. Clinical trials seem so oriented toward single substances, and Parkinson’s is an illness with multiple interacting factors, perhaps requiring more than one substance.

LikeLike