|

# # # # Lithium – one of only three metals that can float on water – is widely used for in the treatment of as a mood stabilizer, primarily in the management of bipolar disorder, mania, and certain types of depression. New research suggests that lithium may be a key piece of the puzzle that is Alzheimer’s. Other researchers are asking if it could also be important in Parkinson’s. In today’s post, we will look at what lithium is, review the new Alzheimer’s research, and consider if it has a possible place in Parkinson’s. # # # # |

A nova. Source: phys.org

A nova. Source: phys.org

While the “big bang” may have created a small amounts of the stuff during the initial formation of the universe, astrophysicist now believe that the majority of our current stock of lithium has been manufactured in the nuclear reactions that have powered nova explosions in the intervening period.

I’m sorry: What?!?

Lithium.

Soft, silvery-white alkali metal.

Crucial for high-energy batteries.

Yeah, that part I am aware of. But what the heck are nova explosions?

A nova explosion is a transient event in the night sky caused the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently “new” star that slowly fades over weeks or months. It is caused by a binary star system in which the pair are too close and long-story-short: Big bright flash of light!

And that is where our lithium is made?

A lot of it, yep.

Lithium is amazing stuff. It has some amazing properties. And recently researchers have reported something interesting about it in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

What did they find?

This is the report of their research:

Title: Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Title: Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Authors: Aron L, Ngian ZK, Qiu C, Choi J, Liang M, Drake DM, Hamplova SE, Lacey EK, Roche P, Yuan M, Hazaveh SS, Lee EA, Bennett DA, Yankner BA.

Journal: Nature. 2025 Sep;645(8081):712-721.

PMID: 40770094 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers wanted to look at metal homeostasis in the Alzheimer’s affected brain.

Homeo-what?

Homeostasis is the process a system goes through to maintain relatively stable equilibrium between interdependent parts. The brain needs to keep everything well balanced in order to function properly, even metals.

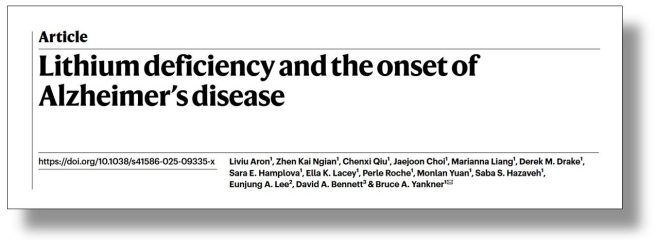

The researchers began their analysis by looking at 27 metals in the brain (and blood) of 133 aged individuals with no cognitive impairment (NCI), 58 individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or 94 people with Alzheimer’s (AD).

A quote from the report: “Of all the metals surveyed, only one, Li, showed significantly reduced levels in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with both MCI and AD”.

And when they say “significantly reduced levels”, what they really meant was that the levels were off the chart!

I mean, just look at lithium (Li) in the logarithmic graphs below:

MCI=Mild cognitive impairment; NCI=No cognitive impairment. Source: PMC

MCI=Mild cognitive impairment; NCI=No cognitive impairment. Source: PMC

While all of the other metal are clustered in the middle, lithium is really out there by itself. Like Voyager 1.

They repeated this analysis in a second set of brain samples from an independent source and they found the same reduced levels of lithium.

Curiously, when they looked in the blood samples that they had, Lithium levels in MCI and Alzheimer’s cases were not significantly different from controls.

Naturally these observations grabbed the attention of the researchers, and they decided to have a closer look at lithium in the brains of people with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s..

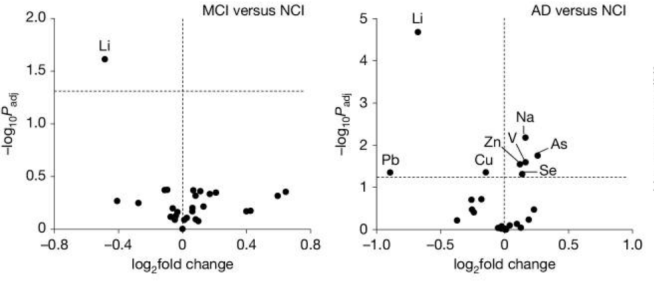

How did they do that?

They used a technique called laser capture microdissection, which allows one to use a laser to cut out tiny sections of tissue from brain slices for molecular analysis. These tiny sections are caught in a test tube and then analysed in various assays.

Laser capture microdissection. Source: Leica

Laser capture microdissection. Source: Leica

And this is where the researchers made a second fascinating discovery.

What did they find?

Before we discuss that, we need to talk about the pathology of dementia/Alzheimer’s.

When scientists look at the postmortem brain of a person with dementia, they firstly find atrophy (or shrinkage) of the brain. But when they look even closer, they also find deposits of a protein called amyloid beta (Aβ).

Aβ is a protein that clumps together forming what we call “plaques”. These plaques form outside of neurons in the brain. This video does a good job of explaining the pathology of Alzheimer’s for anyone who would like to know more:

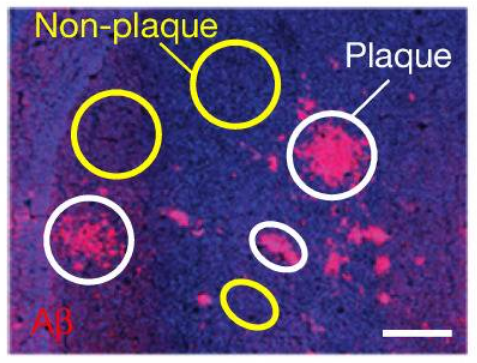

When the lithium investigators used the laser capture microdissection machine to cut out tiny sections of brain tissue from the brains of people who died with Alzheimer’s, they found that some of their collected samples contained these Aβ plaques, while other samples did not:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

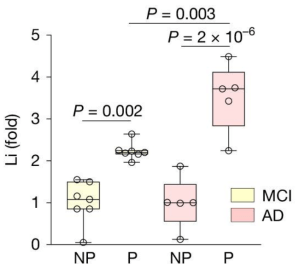

In the samples without Aβ plaques, the researchers found very low levels of lithium, while in the samples that contained Aβ plaques, the researchers found extremely high levels of lithium.

A quote from the report: “A highly significant concentration of Li in Aβ plaques was detected in every case of MCI and AD, which increased from MCI to AD”.

NP=No plaque samples; P=plaque-enriched samples. Source: PMC

NP=No plaque samples; P=plaque-enriched samples. Source: PMC

Interesting. So lithium is somehow getting stuck in these Aβ plaques?

Yes, And another interesting detail was that lower levels of lithium in the samples of that didn’t contain plaques correlated with lower cognitive test scores “across the entire ageing population”.

Next the researchers turned their attention to mice.

Specifically, they looked at mice that were genetically engineered to produce high levels of Aβ plaques in their brains.

Specifically, they looked at mice that were genetically engineered to produce high levels of Aβ plaques in their brains.

And guess what?

When they used the laser capture microdissection machine on brain sections from these mice, the investigators found 3-4x higher levels of lithium in the samples that contained Aβ plaques (compared to the samples that did not contain Aβ plaques).

So what happens if you give the mice more lithium in their diet?

Great question!

Thank you.

Strange answer though.

How so?

Well, you would think that if you lowered the amount of lithium in diet of these mice (that produce high levels of Aβ in their brains), that you might see less plaques in their brains.

But you would be wrong.

When they reduced the level of lithium in the diet of the mice, the scientists observed a significant elevation in Aβ deposition in the brain. That is to say, lithium deficiency accelerated Aβ deposition in these Alzheimer’s mice.

The low lithium diet in these mice also significantly impaired learning and long-term memory in the cognitive tests that the researchers used in their study.

Interesting. So what happens if you give the mice lithium?

Another great question.

Thank you. I’m on a roll.

This is exactly what the researchers did next.

But they first looked at which type of lithium to use for this experiment.

What do you mean “which type of lithium”? There’s only one lithium, right?

Yes, there is only one “elemental” lithium.

But as an element, lithium is a highly reactive metal that reacts violently with water and oxygen. These properties make it completely unsafe and biologically incompatible for direct consumption. In fact, because of this high reactivity, pure elemental lithium is not found in nature. Rather, it is usually present as a constituent of salts or other compounds. These salts help to keep it stable and it is this stability that has allowed it to be safely ingested and used as medication.

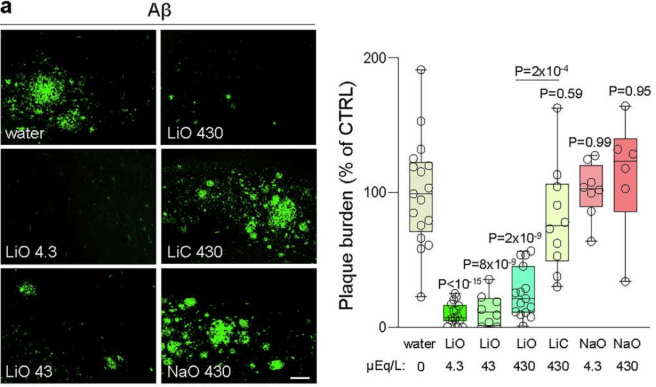

There are lots of different lithium salts, and the researchers in the study we are reviewing wanted to determine which of these salts is less likely to bind with Aβ deposition in the brain. In this fashion, the lithium salt would be free and available to perform biological functions. So the investigators took 16 different lithium salts and assessed them for their ability to bind with Aβ protein.

This analysis identified the organic lithium salt – lithium orotate – as exhibiting reduced binding to Aβ (compared to the clinical standard lithium carbonate). Lithium orotate was also more effective at elevating free lithium in the brains of mice (compared to lithium carbonate). So the scientists had the “type” of lithium that they needed to assess the effect of increasing the lithium levels in the diet of the Alzheimer’s mice. And they were able to proceed with the experiment.

And what did they find?

Remarkably, when lithium orotate was administered to the genetically engineered Alzheimer’s mice, it almost completely prevented Aβ plaque deposits in the brains of the mice. The lithium orotate was administered to the mice via their drinking water from 5–12 months of age.

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

At what age to these mice start to develop plaques?

The genetically engineered mice (called 3xTg mice) typically start to have plaques appearing in their brains around 5-6 months of age (mice generally live 2 years).

So the researchers were treating the mice with lithium orotate before the plaques appear?

Yes. But the next experiment they conducted looked at late initiation of lithium orotate treatment. With a new group of mice, they started putting the lithium orotate in their drinking water from 9 to 18 months of age. In this way, the mice would already have plaques in their brain at the initiation of treatment.

And what happened?

The researchers found that the late initiation of lithium orotate treatment significantly reduced the Aβ plaque burden in the brains of the mice, while lithium carbonate had no impact on the plaques.

Do the researchers have any ideas on how this lithium-based effect works?

Yes, they did some deep diving into the biology and they found that the lithium deficiency altered the behaviour of microglia in the brain. Specifically, they activated the microglia.

Ok, but what are microglia?

Microglia are some of the helper cells in the brain, they provide supportive services to neurons. Specifically, they act as the resident immune cells. When infection or damage occurs, the microglia become ‘activated’ and start cleaning up the area.

Different types of cells in the brain. Source: Dreamstime

Different types of cells in the brain. Source: Dreamstime

When they become activated, microglia do generally do three things:

1. They change shape – microglia usually have outstretched branches when they are in their ‘resting’ state. These branches are constantly monitoring the surrounding environment for any signs of trouble. But when trouble appears, microglia will become activated and retract their branches, giving them a more spherical appearance.

Source: Diacomp

Source: Diacomp

2. They release cytotoxic proteins – these toxic messenger proteins (called cytokines) encourage a wounded or sick cell to die, helping the microglia to determine which cells are too sick/damage to survive and need to be removed.

Source: Sigmaaldrich

Source: Sigmaaldrich

3. They start to be very active with regards to phagocytosis.

What is phagocytosis?

Phagocytosis comes from Ancient Greek φαγεῖν (phagein) , meaning ‘to eat’, and κύτος, (kytos) , meaning ‘cell’. It is used in biology to refer to the process of engulfing or consuming objects.

A schematic of a macrophage. Source: Meducator

A schematic of a macrophage. Source: Meducator

Microglial phagocytosis is a process by which dying cells/debris/rubbish can be vacuumed up, broken down and disposed of (Click here to read a good review of microglia-based phagocytosis in the context of Parkinson’s).

By doing this amazing clean up job, microglia are able to help maintain ‘homeostasis’ in the brain.

But here is where lithium comes into play.

How so?

The researchers found that while lithium deficiency activated microglia, it also impaired the ability of microglia to phagocytose and degrade Aβ. Thus, lithium deficiency was associated with elevated levels of Aβ plaques.

|

# RECAP #1: Lithium is a elemental metal that is used as a mood stabilizer for conditions like depression and bipolar disorder. Recently researchers have found that lithium levels in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s are significantly reduced, and this reduction is associated with cognitive decline. The investigators also identified a lithium salt (lithium orotate) that when administered can be used to restore homeostasis in the brains of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s. # |

Fascinating. Has anyone ever tested lithium in people with Alzheimer’s before?

Yes.

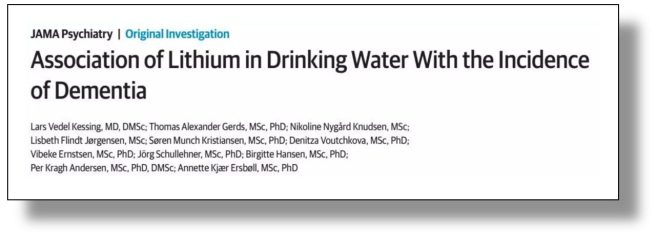

First, there is epidemiological research suggesting that lithium in drinking water was associated with reduced incidence of dementia.

This report was published in 2017:

Title: Association of Lithium in Drinking Water With the Incidence of Dementia.

Title: Association of Lithium in Drinking Water With the Incidence of Dementia.

Authors: Kessing LV, Gerds TA, Knudsen NN, Jørgensen LF, Kristiansen SM, Voutchkova D, Ernstsen V, Schullehner J, Hansen B, Andersen PK, Ersbøll AK.

Journal: JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;74(10):1005-1010.

PMID: 28832877 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers conducted a nationwide (Denmark), population-based, nested case-control study involving 73 731 individuals with dementia and 733 653 cognitively normal “control” individuals. The investigators examined longitudinal, individual geographic data (assessing the municipality of residence for each individual) and the longitudinal data from drinking water measurements with those geographies.

They found that long-term low-dose lithium exposure in drinking water may be associated with a lower incidence of dementia. The researchers were quick to point out though that other confounding factors within certain municipality of residence cannot be excluded in influencing this association.

But more recently, additional data has supported this association (Click here to read more about this).

And then there is also the clinical trials.

Back in 2011, researchers in Brazil published the results of a clinical study in which they had evaluated the effect of long-term lithium treatment on cognitive and biological outcomes in people with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI).

This is the report:

Title: Disease-modifying properties of long-term lithium treatment for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomised controlled trial.

Title: Disease-modifying properties of long-term lithium treatment for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomised controlled trial.

Authors: Forlenza OV, Diniz BS, Radanovic M, Santos FS, Talib LL, Gattaz WF.

Journal: Br J Psychiatry. 2011 May;198(5):351-6.

PMID: 21525519 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators conducted a 12-month, double-blind trial, in which they administered lithium to 24 people with aMCI and a placebo treatment to an additional 21 individuals. The primary outcome measures of the study were cognitive and functional test scores (Click here to read more about this study). The researchers found that lithium treatment was associated with decrease in biomarker concentrations (P-tau) and better performance on the cognitive tasks. The investigators suggested a larger study was required to better assess the effects of lithium.

Then in 2013, another report was published: Title: Microdose lithium treatment stabilized cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Title: Microdose lithium treatment stabilized cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Authors: Nunes MA, Viel TA, Buck HS.

Journal: Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013 Jan;10(1):104-107.

PMID: 22746245

Following the publication of a research report indicating that lithium-treated bipolar patients had a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s (Click here to read more about this), the researchers behind this report conducted a clinical study evaluating micro-doses of lithium (300ug once daily for 15 months) in 58 people with Alzheimer’s (comparing them to 55 people on a placebo treatment). The researchers reported that the lithium treated group showed no decrease in the performance in the mini-mental state examination test (a common measure of memory and cognition), while the placebo group continued to decline in performance.

More recently, another clinical study has looked at low dose lithium in Alzheimer’s patients, but this investigation was focused on whether lithium could reduce agitation.

This is the report of the results:

Title: Low Dose Lithium Treatment of Behavioral Complications in Alzheimer’s Disease: Lit-AD Randomized Clinical Trial.

Title: Low Dose Lithium Treatment of Behavioral Complications in Alzheimer’s Disease: Lit-AD Randomized Clinical Trial.

Authors: Devanand DP, Crocco E, Forester BP, Husain MM, Lee S, Vahia IV, Andrews H, Simon-Pearson L, Imran N, Luca L, Huey ED, Deliyannides DA, Pelton GH.

Journal: Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022 Jan;30(1):32-42.

PMID: 34059401 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators assessed 58 people with Alzheimer’s (half on placebo and half on lithium carbonate for 12 weeks, and while low-dose lithium had no effect in treating agitation, it was associated with overall clinical improvement (although the difference was small)..

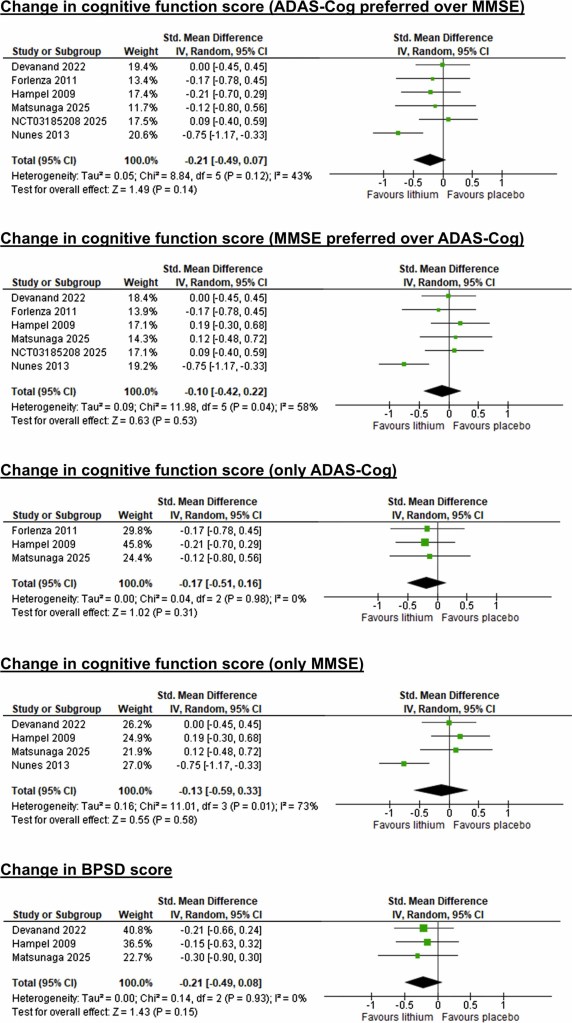

A very recent meta-analysis of the data investigating lithium in people with Alzheimer’s adds further support to the research discussed above:

Title: Lithium for Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from a meta-analysis.

Title: Lithium for Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from a meta-analysis.

Authors: Kishi T, Matsunaga S, Saito Y, Iwata N.

Journal: Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2026 Jan;180:106458.

PMID: 41205642 (This review is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers pooled all of the data from six studies that have investigated lithium supplementation in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and/or Alzheimer’s. When they looked at all of the results, they concluded lithium carbonate, lithium gluconate, and lithium sulfate supplementation “did not significantly delay cognitive impairment progression in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s compared with placebo“. As you can see in the image below, there were trends in favour of lithium use across many of the tests used, but the inconsistent results across the studies make it difficult to suggest any superiority of lithium over placebo:

Source: ScienceDirect

Source: ScienceDirect

So at present, while there have been clinical trials testing lithium in dementia, they have generally been small and the results have been inconclusive.

In addition, in all of these studies the investigators used lithium carbonate, lithium gluconate, or lithium sulfate supplementation to test their hypotheses, and as the data above (in the mouse studies) indicates lithium orotate might be the more appropriate approach.

Has lithium orotate been tested in humans?

Not so much.

There are one or two very old studies (Click here for an example), but before any proper clinical trial is conducted, more extensive testing of lithium orotate would be required (assessing safety and dose ranging).

The most recent study I could find was a small, 28 day brain imaging study involving 9 healthy volunteers. The lithium orotate treatment was well-tolerated in all participants (Click here to read more about this).

|

# # RECAP #2: Epidemiological data indicates that low levels of lithium in water supply is associated with a reduced risk of developing dementia. Multiple small clinical trials have provided some encouraging indications that lithium may be a useful treatment for Alzheimer’s, but larger, more carefully designed studies are required to really test if the agent is having an impact. Limited data is currently available for lithium orotate in humans. # # |

Ok, this is all very encouraging for Alzheimer’s, but what does it have to do with Parkinson’s?

In 1981, a group of researchers reported the case of a 42-year-old man with Parkinson’s who had developed “ON-OFF” episodes. Given preclinical research at the time was indicating that lithium could reduce the supersensitivity of dopamine receptors (Click here to read more about this), the investigators started treating the man with lithium, and this resulted in an 80% reduction in the number of hours in the OFF state. In addition, they reported that this was effect maintained during eight months of follow-up (Click here to read more about this).

Encouraged by this result, the researchers started a small clinical study and the results were published in 1982:

Title: Treatment of the “on-off” phenomenon in Parkinsonism with lithium carbonate.

Title: Treatment of the “on-off” phenomenon in Parkinsonism with lithium carbonate.

Authors: Coffey CE, Ross DR, Ferren EL, Sullivan JL, Olanow CW.

Journal: Ann Neurol. 1982 Oct;12(4):375-9.

PMID: 6816132

In this study, the researchers recruited 6 people with Parkinson’s who had significant daily OFF-time, to take part in an open label study. They were started on low-dose of lithium carbonate. Starting 1-3 weeks after reaching target lithium levels (0.6 to 1.2

mEq/L)., 5 of the 6 participants reported a marked decrease in their “OFF” activity. This decrease ranged from 50 to 83% (average follow up period was 36 weeks).

At the dose used in this study, however, two of the male participants developed “a marked increase in dyskinesia“. Dyskinesia are involuntary, uncontrollable body movements like jerking, twitching, or writhing, often believed to be a side effect of long-term use of levodopa (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic). And following this study, further clinical testing found additional cases of dyskinesia (Click here to read more about this).

So it sounds like lithium might not be so useful?

Well, it is important to understand that those old studies were conducted using a normal dose of lithium – the same used in the treatment of depression (therapeutic serum lithium concentration (0.6 to 1.2mEq/L)).

Which raises the question of whether a lower dose might be useful.

And this is where Professor Tom Guttuso comes into the story:

Professor Tom Guttuso. Source: FB

Professor Tom Guttuso. Source: FB

He is a a movement disorder neurologist at the University of Buffalo, and he has a strong interest in lithium when it comes to Parkinson’s.

Prof Guttuso became interested in lithium when one of his patients came to him with an interesting observation. The patient explained that his most severe and difficult-to-treat Parkinson’s symptoms were motor fluctuations, and that these ON-OFF episodes were almost completely resolved after the patient’s psychiatrist put him on a low dose

of lithium. The psychiatrist had done this to help treat the bipolar disorder that the patient also suffered from.

Prof Guttuso was intrigued, because the only association he had heard of regarding lithium and Parkinson’s was that of lithium toxicity – where high doses sometimes actually cause Parkinson’s-like symptoms. He next read up on the previous clinical trials of lithium in Parkinson’s (discussed above) and questioned why his patient had not developed dyskinesias like the participants had in those trials.

Recalling a quote from a 16th-century Swiss physician, Paracelsus (“The dose makes the poison”), Prof Guttuso decided that the low dose his patient was taking might be the key difference.

And so he initiated a small clinical trial, which was published in 2023:

Title: Lithium’s effects on therapeutic targets and MRI biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot clinical trial.

Title: Lithium’s effects on therapeutic targets and MRI biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot clinical trial.

Authors: Guttuso T Jr, Shepherd R, Frick L, Feltri ML, Frerichs V, Ramanathan M, Zivadinov R, Bergsland N.

Journal: IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2023 May 7;14:429-434.

PMID: 37215748 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, Prof Guttuso and collaborators conducted an open-label pilot study, in which they randomized 16 people with Parkinson’s to different doses of “low-dose” lithium. Five of the participants were allocated to the “high-dose” group (lithium carbonate titrated to achieve serum level of 0.4–0.5 mmol/L). Another 6 participants were placed in the “medium-dose” group (45 mg/day lithium aspartate). And then the remaining 5 participants were assigned to the “low-dose” group (15 mg/day lithium aspartate). All of the participants self administered their lithium therapy daily for 24-weeks (Click here to read more about the study).

Given that the study was so small and open label, the investigators focused on blood-based biomarkers to determine if the lithium treatment had any effect. These biomarkers were levels of nuclear receptor-related-1 (NURR1) and superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) in the blood of the participants.

What is NURR1?

NURR1 is a transcription factor – this is a protein that is involved in the process of converting (or transcribing) DNA into RNA. NURR1 is very important for activating the transcription of a number of genes that are required for making and maintaining a dopamine neuron.

If there is no NURR1, there is no dopamine. And increasing NURR1 is assumed to have positive effects in the context of Parkinson’s (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on NURR1).

Ok, what about SOD1? What is that?

SOD1 (Superoxide Dismutase 1) is a vital enzyme that neutralizes toxic superoxide radicals in the body, Consider it a naturally occurring super antioxidant (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic).

By looking at NURR1 and SOD1 levels in the blood, the researchers hoped to get a surrogate measure of what is happening in the brain.

OK. Interesting biomarkers. What did the investigators find in their study?

In the medium dose group the researchers observed a 679% increase in NURR1 levels and a 127% increase in SOD1.

Wow. That sounds like a lot.

It is. But remember that this is a very small study of only 4-5 people per dosing arm. And what is also interesting is that the medium dose group were the only participants that had a numerical decrease in free water imaging measures.

What is free water imaging?

Free water imaging is a brain imaging technique that separates brain tissue water into two components:

- Restricted water (the fluid that is within cells/fibers)

- “Free” water (the fluid that is in the extracellular space, like cerebrospinal fluid

This allows researchers to investigate neurodegeneration more sensitively than standard MRI brain imaging, making it a powerful tool for Parkinson’s research.

This video will explain how free water imaging works within the context of Alzheimer’s:

At the end of their 24 week treatment period, the Prof Guttuso and colleagues found that the medium dose treatment group had decreases in brain free water in all three of the regions of interest that were measured in the study. A reduction in free water is the opposite of the known longitudinal changes in Parkinson’s, suggesting a positive effect.

Before we get too excited about this, the researchers were very quick to point out that given the small cohort of participants in their study, it is very difficult to make any firm conclusions. But the preliminary data is encouraging and worthy of further investigation.

|

# FULL DISCLOSURE: The author of this blog is the director of research at Cure Parkinsons. The charity is currently funding follow up research to Prof Guttuso’s initial pilot study. # |

So what does it all mean?

Johan August Arfwedson discovered lithium in 1817 – the same year that James Parkinson’s described the condition that bears his name. Arfwedson found the element while analysing the mineral petalite that had been extracted from a mine in Utö, Sweden. He identifying it as a new alkali metal and named it “lithion” (from the Greek lithos, meaning stone).

Johan August Arfwedson. Source: Wikipedia

Johan August Arfwedson. Source: Wikipedia

From there lithium had a patchy history until John Cade began testing it at Bundoora Repatriation Hospital (a veterans’ hospital in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia) in 1949 (Click here to read a good history of lithium as a medicine). Cade’s work demonstrated the medical utility of lithium and it has become widespread.

New research suggests that lithium may have a role in dementia and supplementation of certain versions of lithium salts could be useful to the treatment of conditions like Alzheimer’s. There is also encouraging research being conducted in Parkinson’s. But it is important to point out the dangers of lithium – which we only briefly touched on above.

It is a remarkable element, but it has a “Goldilocks”-like nature when used as medication. Dosing (and blood levels) must be very carefully controlled, otherwise unwanted side effects are likely to be experienced. So this is not a medication to be playing with (Click here to read more about the potential side effects of lithium).

It is evident, from the research discussed in this post, that more research into “low-dose” lithium is required. For example, it would be interesting to see if (and how) lithium interacts with some of the proteins associated with Parkinson’s (particularly the aggregating ones such as alpha synuclein). And it will be important to further explore some of the differences between the various lithium salts.

Born in exploding stars, but potentially of great importance down here on little old Earth.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR S NOTE: The author of this post is an employee of Cure Parkinson s, so he might be a little bit biased in his views on research and clinical trials supported by the trust. That said, the trust has not requested the production of this post, and the author is sharing it simply because it may be of interest to the Parkinson s community.

The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken based on what has been read on the website are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from outlookbusiness

Great article. Should be updated to add the results of the LATTICE trial in MCI (NCT03185208, on SSRN and clinicaltrials dot gov):

They unfortunately used Li carbonate (150 or 300 mg). Still, it significantly slowed the decline of verbal memory (p=0.048), despite a 36% medication discontinuation rate. But it failed to show a significant impact on global cognition, brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels, or cortical gray matter volume. Benefits were driven by the amyloid-positive subgroup vs negligible in amyloid-negative participants.

As they conclude: “Alternative formulations of lithium, such as lithium orotate, also warrant further investigation in human RCTs since lithium orotate may be effective at concentrations orders of magnitude less than lithium carbonate with much less toxicity.”

Unfortunately, Prof Guttuso used Li aspartate (which is somewhere between carbonate and orotate in terms of conductivity) based on the reasoning that Li orotate might cause cancer (JAMA Netw Open e2436874, refs 34–36). Assuming the 3 cited papers are correct and scalable to humans, you’d have to take ~300 mg of Li as Li orotate to have some carcinogenic risk. But based on the Nature paper (and the experience of “biohackers” who have been successfully supplementing with Li orotate for decades), only 1 to 5 mg per day of Li orotate might be enough. Cow’s milk contains 100 mg of orotic acid per liter. 1 mg Li as orotate per day = one glass of milk… 0 lithium toxicity or adverse events at this low dose but potentially 10x more potent than Li as asparate and 100x mg of Li as carbonate?

LikeLike

I wonder if anyone has looked at Parkinson’s incidence in areas with naturally high lithium such as Cornwall (associated with granite geology), where presumably the drinking water has an elevated Li content. I can not quickly find any maps showing either stream water chemistry or drainage sediment chemistry, but I presume the British Geological Survey could help with that.

Some research is also available that suggests a link between naturally high lithium levels in drinking water and a lower suicide rate, but I can not find any stats wrt drinking water lithium content and Parkinson’s.

LikeLike