A new research report looking at the use of cholesterol-reducing drugs and the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease has just been published in the scientific journal Movement disorders.

The results of that study have led to some pretty startling headlines in the media, which have subsequently led to some pretty startled people who are currently taking the medication called statins.

In todays post, we will look at what statins are, what the study found, and discuss what it means for our understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

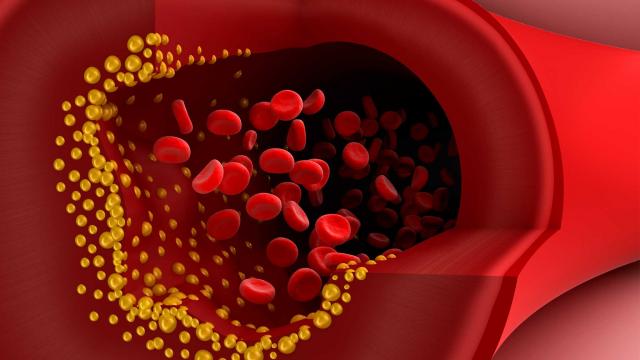

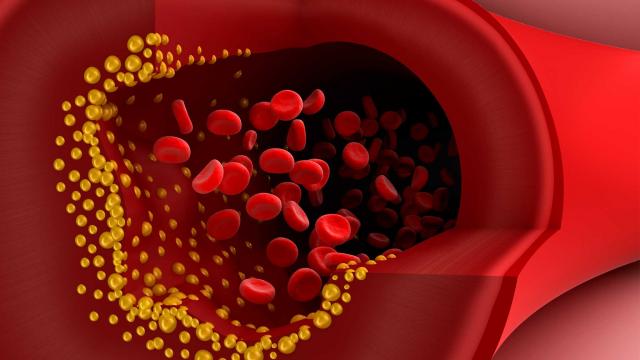

Cholesterol forming plaques (yellow) in the lining of arteries. Source: Healthguru

Cholesterol gets a lot of bad press.

Whether it’s high and low, the perfect balance of cholesterol in our blood seems to be critical to our overall health and sense of wellbeing. At least that is what we are constantly being told this by media and medical professionals alike.

But ask yourself this: Why? What exactly is cholesterol?

Good question. What is cholesterol?

Cholesterol (from the Greek ‘chole‘- bile and ‘stereos‘ – solid) is a waxy substance that is circulating our bodies. It is generated by the liver, but it is also found in many foods that we eat (for example, meats and egg yolks).

The chemical structure of Cholesterol. Source: Wikipedia

Cholesterol falls into one of three major classes of lipids – those three classes of lipids being Triglycerides, Phospholipids and Steroids (cholesterol is a steroid). Lipids are major components of the cell membranes and thus very important. Given that the name ‘lipids’ comes from the Greek lipos meaning fat, people often think of lipids simply as fats, but fats more accurately fall into just one class of lipids (Triglycerides).

Like many fats though, cholesterol dose not dissolve in water. As a result, it is transported within the blood system encased in a protein structure called a lipoprotein.

The structure of a lipoprotein; the purple C inside represents cholesterol. Source: Wikipedia

Lipoproteins have a very simple classification system based on their density:

- very low density lipoprotein (VLDL)

- low density lipoprotein (LDL)

- intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL)

- high density lipoprotein (HDL).

Now understand that all of these different types of lipoproteins contain cholesterol, but they are carrying it to different locations and this is why some of these are referred to as good and bad.

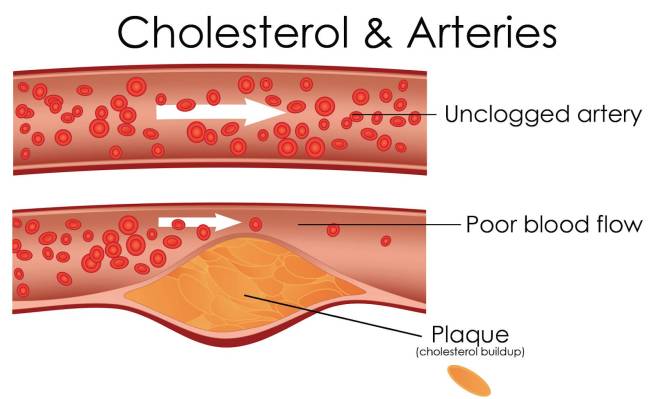

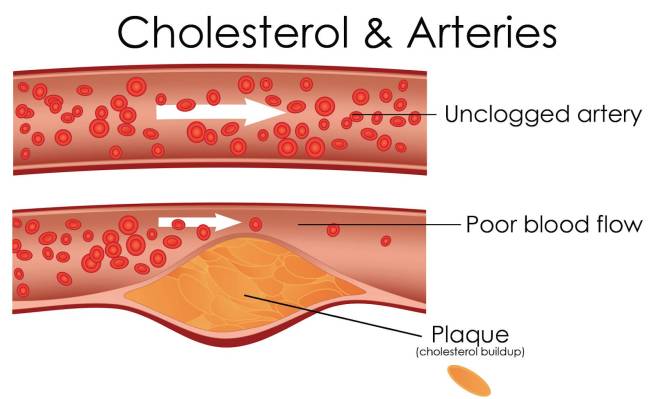

The first three types of lipoproteins carry newly synthesised cholesterol from the liver to various parts of the body, and thus too much of this activity would be bad as it results in an over supply of cholesterol clogging up different areas, such as the arteries.

LDLs, in particular, carry a lot of cholesterol (with approximately 50% of their contents being cholesterol, compared to only 20-30% in the other lipoproteins), and this is why LDLs are often referred to as ‘bad cholesterol’. High levels of LDLs can result in atherosclerosis (or the build-up of fatty material inside your arteries).

Progressive and painless, atherosclerosis develops as cholesterol silently and slowly accumulates in the wall of the artery, in clumps that are called plaques. White blood cells stream in to digest the LDL cholesterol, but over many years the toxic mess of cholesterol and cells becomes an ever enlarging plaque. If the plaque ever ruptures, it could cause clotting which would lead to a heart attack or stroke.

Source: MichelsonMedical

So yeah, some lipoproteins can be considered bad.

HDLs, on the other hand, collects cholesterol and other lipids from cells around the body and take them back to the liver. And this is why HDLs are sometimes referred to as “good cholesterol” because higher concentrations of HDLs are associated with lower rates of atherosclerosis progression (and hopefully regression).

But why is cholesterol important?

While cholesterol is usually associated with what is floating around in your bloodstream, it is also present (and very necessary) in every cell in your body. It helps to produce cell membranes, hormones, vitamin D, and the bile acids that help you digest fat.

It is particularly important for your brain, which contains approximately 25 percent of the cholesterol in your body. Numerous neurodegenerative conditions are associated with cholesterol disfunction (such as Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease – Click here for more on this). In addition, low levels of cholesterol is associated with violent behaviour (Click here to read more about this).

Are there any associations between cholesterol and Parkinson’s disease?

The associations between cholesterol and Parkinson’s disease is a topic of much debate. While there have been numerous studies investigating cholesterol levels in blood in people with Parkinson’s disease, the results have not been consistent (Click here for a good review on this topic).

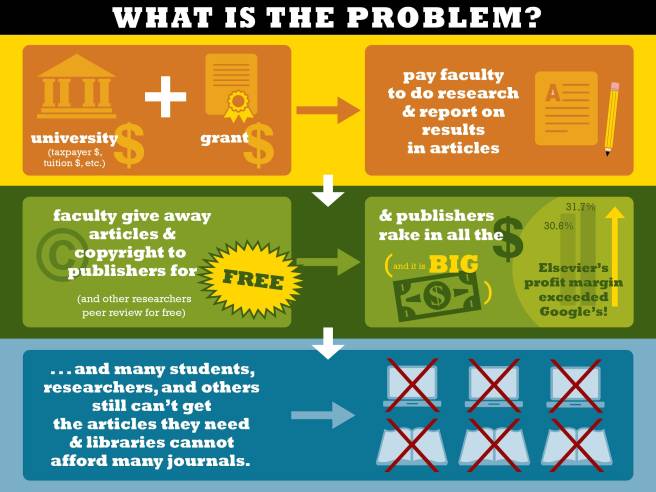

Rather than looking at cholesterol directly, a lot of researchers have chosen to focus on the medication that is used to treat high levels of cholesterol – a class of drugs called statins.

Title: Prospective study of statin use and risk of Parkinson disease.

Authors: Gao X, Simon KC, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A.

Journal: Arch Neurol. 2012 Mar;69(3):380-4.

PMID: 22410446 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study the researchers conduced a prospective study involving the medical details of 38 192 men and 90 874 women from two huge US databases: the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS).

NHS study was started in 1976 when 121,700 female registered nurses (aged 30 to 55 years) completed a mailed questionnaire. They provided an overview of their medical histories and health-related behaviours. The HPFS study was established in 1986, when 51,529 male health professionals (40 to 75 years) responded to a similar questionnaire. Both the NHS and the HPFS send out follow-up questionnaires every 2 years.

By analysing all of that data, the investigators found 644 cases of Parkinson’s disease (338 women and 306 men). They noticed that the risk of Parkinson’s disease was approximately 25% lower among people currently taking statins when compared to people not using statins. And this association was significant in statin users younger than 60 years of age (P = 0.02).

What are statins?

Also known as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, statins are a class of drug that inhibits/blocks an enzyme called 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase.

HMG-CoA reductase is the key enzyme regulating the production of cholesterol from mevalonic acid in the liver. By blocking this process statins help lower the total amount of cholesterol available in your bloodstream.

Source: Myelomacrowd

Statins are used to treat hypercholesterolemia (also called dyslipidemia) which is high levels of cholesterol in the blood. And they are one of the most widely prescribed classes of drugs currently available, with approximately 23 percent of adults in the US report using statin medications (Source).

Now, while the study above found an interesting association between statin use and a lower risk of Parkinson’s disease, the other research published on this topic has not been very consistent. In fact, a review in 2009 found a significant associations between statin use and lower risk of Parkinson’s disease was observed in only two out of five prospective studies (Click here to see that review).

New research published this week has attempted to clear up some of that inconsistency, by starting with a huge dataset and digging deep into the numbers.

So what new research has been published?

Title: Statins may facilitate Parkinson’s disease: Insight gained from a large, national claims database

Authors: Liu GD, Sterling NW, Kong L, Lewis MM, Mailman RB, Chen H, Leslie D, Huang X

Journal: Movement Disorder, 2017 Jun;32(6):913-917.

PMID: 28370314

Using the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database which catalogues the healthcare use and medical expenditures of more than 50 million employees and their family members each year, the researcher behind that study identified 30,343,035 individuals that fit their initial criteria (that being “all individuals in the database who had 1 year or more of continuous enrolment during January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2012, and were 40 years of age or older at any time during their enrolment”). From this group, the researcher found a total of 21,599 individuals who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

In their initial analysis, the researchers found that Parkinson’s disease was positively associated with age, male gender, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and usage of cholesterol-lowering drugs (both statins and non-statins). The condition was negatively associated with hyperlipidemia (or high levels of cholesterol). This result suggests not only that people with higher levels of cholesterol have a reduced chance of developing Parkinson’s disease, but taking medication to lower cholesterol levels may actually increase ones risk of developing the condition.

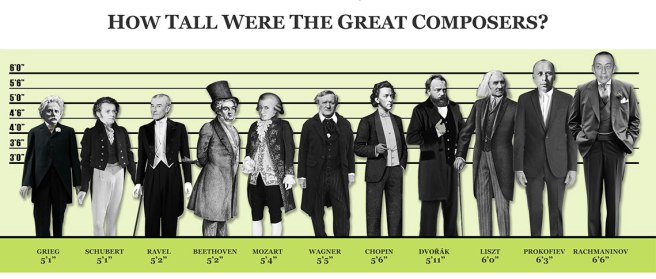

One interesting finding in the data was the effect that different types of statins had on the association.

Statins can be classified into two basic groups: water soluble (or hydrophilic) and lipid soluble (or lipophilic) statins. Hydrophilic molecule have more favourable interactions with water than with oil, and vice versa for lipophilic molecules.

Hydrophilic vs lipophilic molecules. Source: Riken

Water soluble (Hydrophilic) statins include statins such as pravastatin and rosuvastatin; while all other available statins (eg. atorvastatin, cerivastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin) are lipophilic.

In this new study, the researchers found that the association between statin use and increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease was more pronounced for lipophilic statins (a statistically significant 58% increase – P < 0.0001), compared to hydrophilic statins (a non-significant 19% increase – P = 0.25). One possible explanation for this difference is that lipophilic statins (like simvastatin and atorvastatin) cross the blood-brain barrier more easily and may have more effect on the brain than hydrophilic ones.

The investigators also found that this association was most robust during the initial phase of statin treatment. That is to say, the researchers observed a 82% in risk of PD within 1 year of having started statin treatment, and only a 37% increase five years after starting statin treatment.; P < 0.0001). Given this finding, the investigators questioned whether statins may be playing a facilitatory role in the development of Parkinson’s disease – for example, statins may be “unmasking” the condition during its earliest stages.

So statins are bad then?

Can I answer this question with a diplomatic “I don’t know”?

It is difficult to really answer that question based on the results of just this one study. This is mostly because this new finding is in complete contrast to a lot of experimental research over the last few years which has shown statins to be neuroprotective in many models of Parkinson’s disease. Studies such as this one:

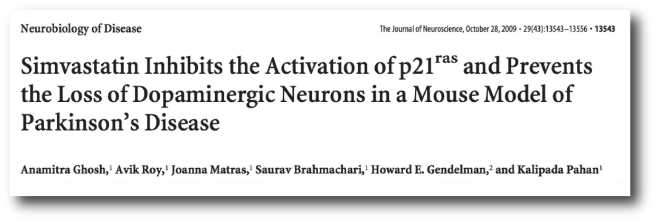

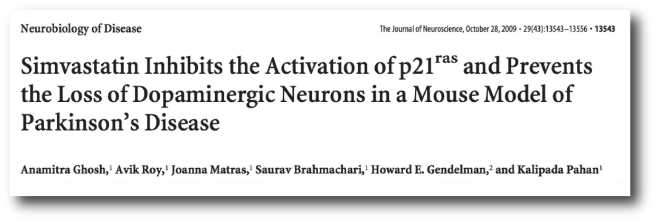

Title: Simvastatin inhibits the activation of p21ras and prevents the loss of dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Ghosh A, Roy A, Matras J, Brahmachari S, Gendelman HE, Pahan K.

Journal: J Neurosci. 2009 Oct 28;29(43):13543-56.

PMID: 19864567 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers found that two statins (pravastatin and simvastatin – one hydrophilic and one lipophilic, respectively) both exhibited the ability to suppress the response of helper cells in the brain (called microglial) in a neurotoxin model of Parkinson’s disease. This microglial suppression resulted in a significant neuroprotective effect on the dopamine neurons in these animals.

Another study found more Parkinson’s disease relevant effects from statin treatment:

TItle: Lovastatin ameliorates alpha-synuclein accumulation and oxidation in transgenic mouse models of alpha-synucleinopathies.

Authors: Koob AO, Ubhi K, Paulsson JF, Kelly J, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Adame A, Masliah E.

Journal: Exp Neurol. 2010 Feb;221(2):267-74.

PMID: 19944097 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers treated two different types of genetically engineered mice (both sets of mice produce very high levels of alpha synuclein – the protein closely associated with Parkinson’s disease) with a statin called lovastatin. In both groups of alpha synuclein producing mice, lovastatin treatment resulted in significant reductions in the levels of cholesterol in their blood when compared to the saline-treated control mice. The treated mice also demonstrated a significant reduction in levels of alpha synuclein clustering (or aggregation) in the brain than untreated mice, and this reduction in alpha synuclein accumulation was associated with a lessening of pathological damage in the brain.

So statins may not be all bad?

One thing many of these studies fail to do is differentiate between whether statins are causing the trouble (or benefit) directly or whether simply lowering cholesterol levels is having a negative impact. That is to say, do statins actually do something else? Other than lowering cholesterol levels, are statins having additional activities that could cause good or bad things to happen?

Source: Liverissues

The recently published study we are reviewing in this post suggested that non-statin cholesterol medication is also positively associated with developing Parkinson’s disease. Thus it may be that statins are not bad, but rather the lowering of cholesterol levels that is. This raises the question of whether high levels of cholesterol are delaying the onset of Parkinson’s disease, and one can only wonder what a cholesterol-based process might be able to tell us about the development of Parkinson’s disease.

If the findings of this latest study are convincingly replicated by other groups, however, we may need to reconsider the use of statins not in our day-to-day clinical practice. At the very least, we will need to predetermine which individuals may be more susceptible to developing Parkinson’s disease following the initiation of statin treatment. It would actually be very interesting to go back to the original data set of this new study and investigate what addition medical features were shared between the people that developed Parkinson’s disease after starting statin treatment. For example, were they all glucose intolerant? One would hope that the investigators are currently doing this.

Are Statins currently being tested in the clinic for Parkinson’s disease?

(Oh boy! Tough question) Yes, they are.

There is currently a nation wide study being conducted in the UK called PD STAT.

The study is being co-ordinated by the Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust (Devon). For more information, please see their website or click here for the NHS Clinical trials gateway website.

Is this dangerous given the results of the new research study?

(Oh boy! Even tougher question!)

Again, we are asking this question based on the results of one recent study. Replication with independent databases is required before definitive conclusions can be made.

There have, however, been previous clinical studies of statins in neurodegenerative conditions and these drugs have not exhibited any negative effects (that I am aware of). In fact, a clinical trial for multiple sclerosis published in 2014 indicated some positive results for sufferers taking simvastatin:

Title: Effect of high-dose simvastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial.

Authors: Chataway J, Schuerer N, Alsanousi A, Chan D, MacManus D, Hunter K, Anderson V, Bangham CR, Clegg S, Nielsen C, Fox NC, Wilkie D, Nicholas JM, Calder VL, Greenwood J, Frost C, Nicholas R.

Journal: Lancet. 2014 Jun 28;383(9936):2213-21.

PMID: 24655729 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this double-blind clinical study (meaning that both the investigators and the subjects in the study were unaware of which treatment was being administered), 140 people with multiple sclerosis were randomly assigned to receive either the statin drug simvastatin (70 people; 40 mg per day for the first month and then 80 mg per day for the remainder of 18 months) or a placebo treatment (70 people).

Patients were seen at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months into the study, with telephone follow-up at months 3 and 18. MRI brain scans were also made at the start of the trial, and then again at 12 months and 25 months for comparative sake.

The results of the study indicate that high-dose simvastatin was well tolerated and reduced the rate of whole-brain shrinkage compared with the placebo treatment. The mean annualised shrinkage rate was significantly lower in patients in the simvastatin group. The researchers were very pleased with this result and are looking to conduct a larger phase III clinical trial.

Other studies have not demonstrated beneficial results from statin treatment, but they have also not observed a worsening of the disease conditions:

Title: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of simvastatin to treat Alzheimer disease.

Authors:Sano M, Bell KL, Galasko D, Galvin JE, Thomas RG, van Dyck CH, Aisen PS.

Journal: Neurology. 2011 Aug 9;77(6):556-63.

PMID: 21795660 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators recruited a total of 406 individuals were mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, and they were randomly assigned to two groups: 204 to simvastatin (20 mg/day, for 6 weeks then 40 mg per day for the remainder of 18 months) and 202 to placebo control treatment. While Simvastatin displayed no beneficial effects on the progression of symptoms in treated individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (other than significantly lowering of cholesterol levels), the treatment also exhibited no effect on worsening the disease.

So what does it all mean?

Research investigating cholesterol and its association with Parkinson’s disease has been going on for a long time. This week a research report involving a huge database was published which indicated that using cholesterol reducing medication could significantly increase one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

These results do not mean that someone being administered statins is automatically going to develop Parkinson’s disease, but – if the results are replicated – it may need to be something that physicians should consider before prescribing this class of drug.

Whether ongoing clinical trials of statins and Parkinson’s disease should be reconsidered is a subject for debate well above my pay grade (and only if the current results are replicated independently). It could be that statin treatment (or lowering of cholesterol) may have an ‘unmasking’ effect in some individuals, but does this mean that any beneficial effects in other individuals should be discounted? If preclinical data is correct, for example, statins may reduce alpha synuclein clustering in some people which could be beneficial in Parkinson’s.

As we have said above, further research is required in this area before definitive conclusions can be made. This is particularly important given the inconsistencies of the previous research results in the statin and Parkinson’s disease field of investigation.

EDITORIAL NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from HarvardHealth

Acetylcysteine. Source:

Acetylcysteine. Source: