Exciting results published this week regarding a small phase 1b clinical trial of a new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. In this post, we shall review the findings of the study and consider what they may mean for Parkinson’s disease.

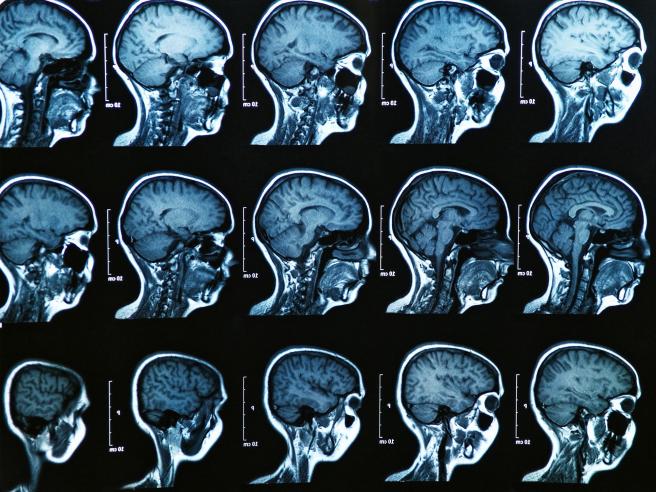

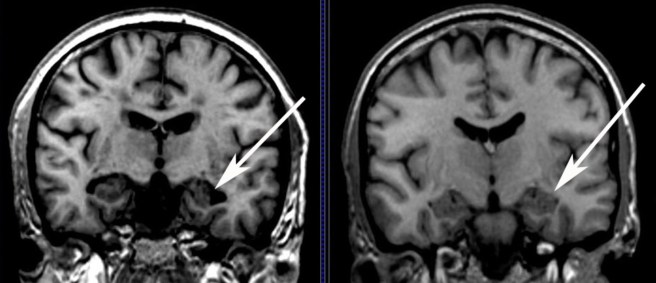

An Alzheimer’s brain scans on the left, compared to a normal brain (right). Source: MedicalExpress

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common neurodegenerative disease, accounting for 60% to 70% of all cases of dementia. It is a progressive neurodegenerative condition, like Parkinson’s disease, affecting approximately 30 million people around the world.

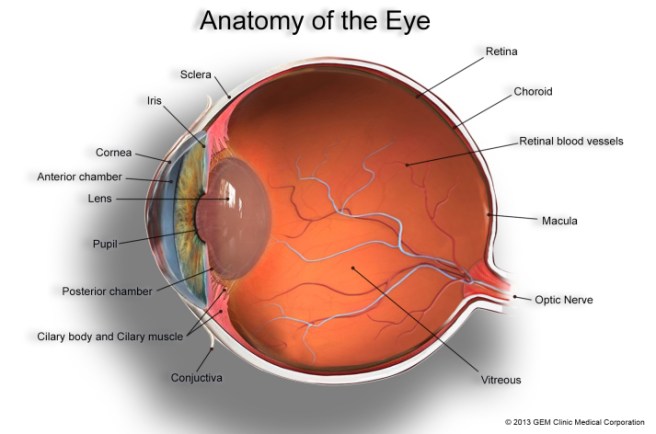

Inside the brain, in addition to cellular loss, Alzheimer’s is characterised by the increasing presence of two features:

- Neurofibrillary tangles

- Amyloid plaques

A schematic demonstrating the difference between healthy and Alzheimer’s affected brains. Source: MmcNeuro

The tangles are aggregations of a protein called ‘Tau’ (we’ll comeback to Tau in a future post). These tangles reside within neurons initially, but as the disease progresses the tangles can be found in the space between cells – believed to be the last remains of a dying cell.

Amyloid plaques are clusters of proteins that outside the cells. A key component of the plaque is beta amyloid. Beta-amyloid is a piece of a larger protein that sits in the outer wall of nerve cells where it has certain functions. In certain circumstances, specific enzymes can cut it off and it floats away.

The releasing of Beta-Amyloid. Source: Wikimedia

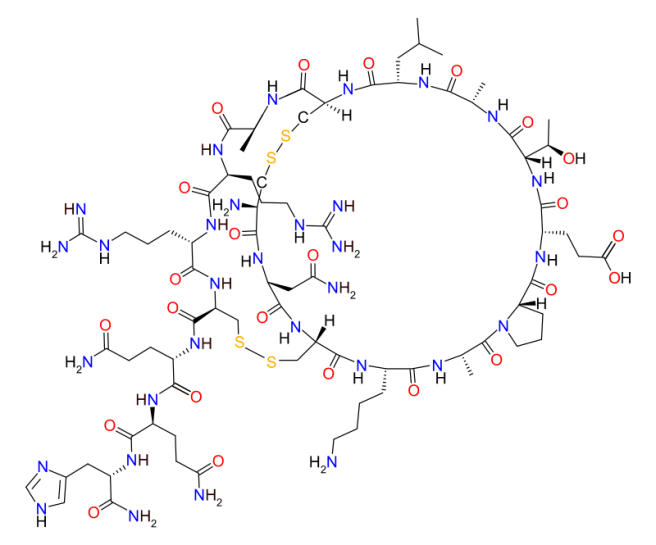

Beta-amyloid is a very “sticky” protein and it has been believed that free floating beta-amyloid proteins begin sticking together, gradually building up into the large amyloid plaques. And these large plaques were considered to be involved in the neurodegenerative process of Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, for a long time scientists have attempted to reduce the amount of free-floating beta-amyloid in the brain. One of the main ways they do this is with antibodies.

What are antibodies?

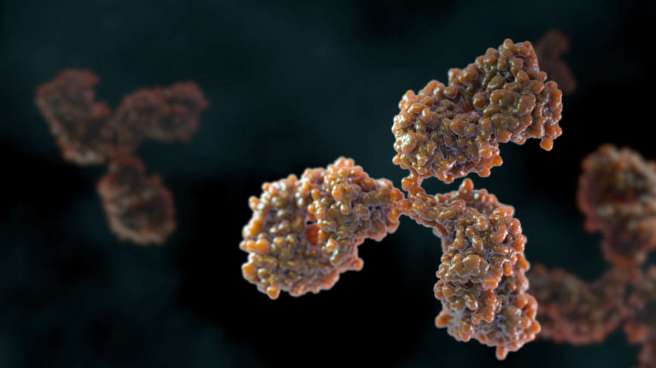

An antibody is the foundation of our immune system. It is a Y-shaped structure, that is used to alert the body when a foreign or unhealthy agent is present.

An artist’s impression of a Y-shaped antibody. Source: Medimmune

Two arms off the Y-shaped antibody have what is called ‘Antigen binding sites‘. An antigen is a molecule that is capable of inducing a response from the immune system (usually a foreign agent, but it can be a sick/dying cell).

A schematic representation of an antibody. Source: Wikipedia

There are currently billions of antibodies in your body -each with specific sets of antigen binding sites – awaiting the presence of their antigen. Antibodies are present in two forms: secreted, free floating antibodies, and membrane-bound antibodies. Secreted antibodies are produced by B-cells, which are part of the immune system. And it’s this secreted form of antibody that modern science has used to produce new medicines.

Really? How does that work?

Scientists can make antibodies in the lab that target specific proteins and then inject those antibodies into a patient’s body and trick the immune system into removing that particular protein. This can be very tricky, and one has to be absolutely sure of the design of the antibody because you do not want any ‘off-target’ effects – the immune system removing a protein that looks very similar to the one you are actually targeting.

These manufactured antibodies are used in many different areas of medicine, particularly cancer (over 40 antibody preparations have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in humans against cancers). Recently, large pharmaceutical companies (like Biogen) have been attempting to use these manufactured antibodies against other conditions, like Alzheimer’s disease.

Which brings us to the study published this week:

Title: The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease.

Authors: Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, Dunstan R, Salloway S, Chen T, Ling Y, O’Gorman J, Qian F, Arastu M, Li M, Chollate S, Brennan MS, Quintero-Monzon O, Scannevin RH, Arnold HM, Engber T, Rhodes K, Ferrero J, Hang Y, Mikulskis A, Grimm J, Hock C, Nitsch RM, Sandrock A.

Journal: Nature. 2016 Aug 31;537(7618):50-6.

PMID: 27582220

In this study, the researcher conducted a 12-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the antibody Aducanumab. This antibody specifically binds to potentially harmful beta-amyloid aggregates (both small and large). At the very start of the trial, each participants was given a brain scan which allowed the researchers to determine the baseline level of beta-amyloid in the brains of the subjects.

All together the study involved 165 people, randomly divided into five different groups: 4 groups received the 4 different concentrations of the drug (1, 3, 6 or 10 mg per kg) and 1 group which received a placebo treatment. Of these, 125 people completed the study which was 12 months long. Each month they received an injection of the respective treatment (remember these are manufactured antibodies, the body can’t make this particular antibody so it has to be repeated injected).

After 12 months of treatment, the subjects in the 3, 6 and 10 mg per kg groups exhibited a significant reduction in the levels of beta-amyloid protein in the brain (according to brain scan images), indicating that Aducanumab – the injected antibody – was doing it’s job. Individuals who received the highest doses of Aducanumab had the biggest reductions in beta-amyloid in the brain. Interestingly, this reduction in beta-amyloid in the brain was accompanied by a slowing of the clinical decline as measured by tests of dementia. Individuals treated with the placebo saw neither any reduction in their brain levels of beta amyloid nor their clinical decline.

The authors considered this study strong justification for larger phase III trials. Two of them are now in progress, with completion dates expected around 2020.

So this is a good thing right?

Yes, this is a very exciting result for the Alzheimer’s community. But the results must be taken with a grain of salt. We have discussed beta-amyloid in a previous post (Click here for that post). While it has long been considered the bad boy of the Alzheimer’s world, the function of beta-amyloid remains the subject of debate. Some researchers worry about the medical removal of it from the brain, especially if it has positive functions like anti-microbial (or disease fighting) properties.

Given that the treatment is given monthly and can thus be controlled, we can sleep easy knowing that disaster won’t befall the patients receiving the antibody. And if they continue to demonstrate a slowing/halting of the disease, it would represent a MASSIVE step forward in the neurodegenerative field. I guess what I am saying is that it is too soon to say. It will be interesting, however, to see what happens as these patients are followed up over time. And the two phase 3 clinical trials currently ongoing, which involve hundreds of participants, will provide a more definitive idea of how well the treatment is working.

So what does this have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

Yeah, so let’s get back to our area of interest: Parkinson’s disease. Biogen is the pharmaceutical company that makes the Alzheimer’s antibody (Aducanumab) discussed above. Biogen is also currently conducting a phase 1 safety trial (on normal healthy adults) of an antibody that targets the Parkinson’s disease associated protein, alpha synuclein. We are currently waiting to hear the results of that trial.

Several other companies have antibody-based approaches for Parkinson’s disease (all of them targeting the protein alpha synuclein). These companies include:

- Prothena – which completed phase 1 safety trials in March 2015 (Click here for more)

- Neuropore – which also completed phase 1 safety trials in March 2015 (Click here for more)

There are some worries regarding this approach, however. For example, alpha synuclein is highly expressed in red blood cells, and some researchers worry about what affects the antibodies may have on their function. In addition, alpha synuclein has been suspected of having anti-viral properties – reducing viruses ability to infect a cell and replicate (click here to read more on this). Thus, removal of alpha synuclein by injecting antibodies may not necessarily be a good thing for the brain’s defense system.

Unlike beta-amyloid, however, most of alpha synuclein’s activities seem to be conducted within the walls of brain cells, where antibodies can’t touch it. Thus the hope is that the only alpha synuclein being affected by the antibody treatment is the variety that is free floating around the brain.

The results of the Alzheimer’s study are a tremendous boost to the antibody approach to treating neurodegenerative diseases and it will be very interesting to watch how this plays out for Parkinson’s disease in the near future.

Watch this space!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from TheNewsHerald