We have previously written about the enormous contribution that the ‘Honolulu Heart Study’ has made to our understanding of Parkinson’s disease. This longitudinal study of 8006 “non-institutionalized men of Japanese ancestry, born 1900-1919, resident on the island of Oahu” has provided some with amazing insight to this condition by allowing us to go back and look at what variables were apparent before people were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read that post).

Earlier this year, some researchers associated with the study reported an interesting observation.

It involved milk.

In today’s post, we’ll discuss what milk might taught us about Parkinson’s disease.

United Providers of Milk. Source: RSPB

In essence, milk is a pale liquid extracted from the mammary glands of mammals.

Riveting stuff, huh?

Ever since glandular skin secretions began with the evolutionary precursors to mammals – the synapsids – milk has remained the primary source of nutrition for infants. In addition to providing sustenance during early life, however, milk also contains colostrum which transfers elements of the mother’s own immune system (specifically antibodies) to the offspring. This exchange gives junior some extra help in strengthening their own developing immune system.

The synapsids family – proto mammals. Source: Feenixx

As infants grow, there is the process of weaning which gradually introduces the infant to a proper diet and reduces the need for the mother’s milk.

A proper diet. Source: Huffington Post

Now this basic idea of milk sustaining and aiding infants worked just fine until about 10,000 years ago, when we humans began doing something rather different:

We began drinking the milk from other mammals.

Sounds disgusting when you write it like that, I know, but between 7000-9000 years ago in south west Asia humans began drinking a lot more milk. Initially sheep’s milk, as it wasn’t until the 14th century that cow’s milk actually became more popular. But today there are more than 250 million cow producing milk for a dairy consuming population of over 6 billion people (despite the fact that milk can be be made in a laboratory – read more here: Cow-less milk).

Drinking milk certainly has it’s benefits:

- one of the best sources of calcium for the body.

- filled with Vitamin D that helps the body absorb calcium.

- contributes to stronger and healthier bones/teeth

- rehydration

But have you ever considered whether there is any downside to drinking milk?

Because there are.

For example, drinking too much milk can impair a child’s ability to absorb iron and given that milk has virtually no iron in it, this can result in increased risk of iron deficiency.

And then, of course, there is that thing that the Honolulu Heart Study told us about milk and Parkinson’s disease.

What did the Honolulu Heart Study tell us about milk and Parkinson’s disease?

The Honolulu Heart Study – a longitudinal study of “non-institutionalized men of Japanese ancestry, born 1900-1919, resident on the island of Oahu” – began in October 1965. In all, 8,006 participants were studied and followed for the rest of their lives (Click here for more on this). 128 of the 8006 individuals enrolled in the study went on to develop Parkinson’s disease, and when the researchers went back and looked at the detail of their lives, they noticed something interesting about milk.

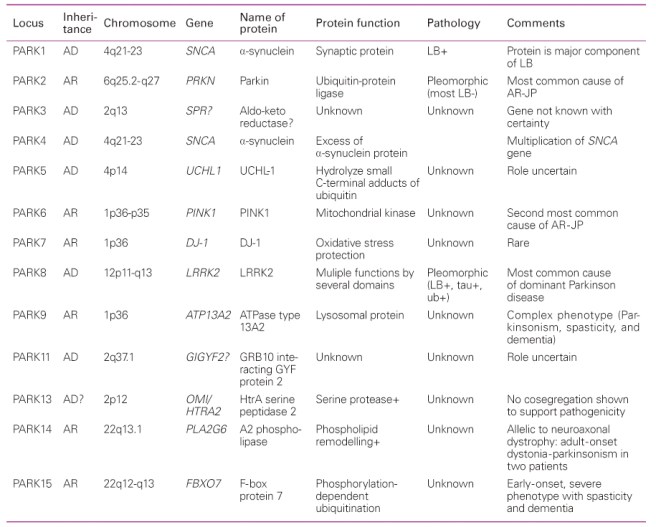

Title: Consumption of milk and calcium in midlife and the future risk of Parkinson disease

Authors: Park M, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Nelson JS, Tanner CM, Curb JD, Blanchette PL, Abbott RD.

Journal: Neurology. 2005 Mar 22;64(6):1047-51.

PMID: 15781824

The researcher found that the incidence of Parkinson’s disease increased with milk intake. In fact, it jumped from 6.9/10,000 person-years in men who consumed no milk to 14.9/10,000 person-years in men who consumed >16 oz/day (approx. 1/2 a litre; p = 0.017). This result suggested that drinking a large cup of milk per day doubled your chances of developing Parkinson’s disease. The researchers noted that this effect was independent of calcium intake. Calcium (from both dairy and nondairy sources) inferred no increase/decrease in the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The effect was specific to milk.

Has anyone replicated this finding?

Unfortunately, yes. Two independent groups have found similar results:

Title: Consumption of dairy products and risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Chen H, O’Reilly E, McCullough ML, Rodriguez C, Schwarzschild MA, Calle EE, Thun MJ, Ascherio A.

Journal: Am J Epidemiol. 2007 May 1;165(9):998-1006.

PMID: 17272289 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

These researchers looked at the subjects (57,689 men and 73,175 women) enrolled in the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort, and found a total of 250 men and 138 women with Parkinson’s disease. Dairy product consumption was positively associated with risk of Parkinson’s disease, 1.8 times that of normal in men and 1.3 times in women. When the dairy products were divided into milk, cheese, yogurt and ice cream, only milk remained significantly associated with an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Dietary and lifestyle variables in relation to incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Greece.

Authors: Kyrozis A, Ghika A, Stathopoulos P, Vassilopoulos D, Trichopoulos D, Trichopoulou A.

Journal: Eur J Epidemiol. 2013 Jan;28(1):67-77.

PMID: 23377703

In this third study, the researchers conducted a population-based prospective cohort study involving 26,173 participants in the EPIC-Greece cohort. After analysing their data the investigators also found a strong positive association between the consumption of milk and Parkinson’s disease. And like the previous study, there was no association with cheese or yoghurt. The effect was again specific to milk.

So what is there something in particular in milk causing this effect?

That is the assumption, but we are not clear on what it is exactly. There is some new evidence, however, hinting that certain contaminants.

And this brings us to the research report from earlier this year:

Title: Midlife milk consumption and substantia nigra neuron density at death

Authors: Abbott RD, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Launer LJ, Nelson JS, White LR, Tanner CM.

Journal: Neurology. 2016 Feb 9;86(6):512-9.

PMID: 26658906

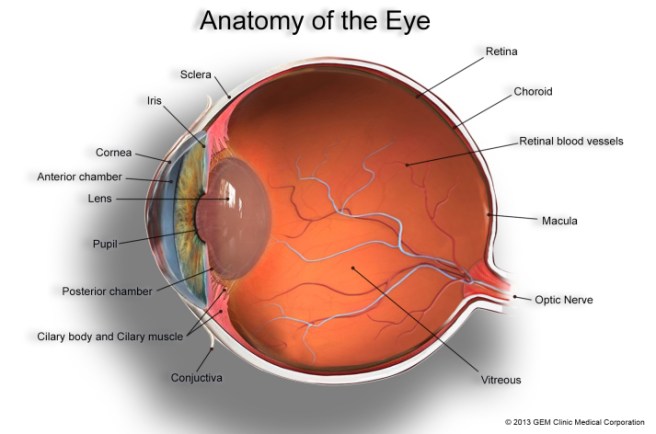

In this study, the researchers looked at the milk intake data for 449 men in the Honolulu Heart Study (which were collected from 1965 to 1968), and then conducted postmortem examinations of their brains (between 1992 to 2004). The researchers found that subjects who drank more than 2 cups of milk per day during their midlife years had approximately 40% fewer dopamine neurons (in certain areas of a region called the substantia nigra where the dopamine neurons live).

But here is the interesting twist in the story:

None of these 449 subjects were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease

These were all neurologically normal/healthy individuals.

Plus this particular effect was only observed among the milk drinking, non-smokers. The milk drinking smokers did not have this cell loss (smoking is associated with a reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s disease – click here for more on this).

The researchers then took the study a step further. They noticed that the cell loss effect was also associated with the presence of heptachlor epoxide in the brain.

What is heptac..whatever?

Heptachlor is an organochlorine compound that was used as an insecticide. Pesticides and insecticides have long been associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (click here to read that post).

In this study, of the 116 brains analysed, heptachlor epoxide was found in 90% of the non-smokers who drank the most milk, but only 63% of those subjects who drank no milk. This lead the researchers to speculate as to whether contamination of milk by heptachlor epoxide could have caused the cell loss. We should point out here that this particular part of the analysis is a wee bit flimsy. The sample size for the non-smoking, high milk consumption group was very small: only 12 individuals.

So what does it all mean?

It means I am now dairy free.

EDITORIAL NOTE HERE: While we do not expect this post to crash the world wide milk market, we did not want to frighten any readers out of their habit of drinking milk. It should be noted here that the daily intake of milk associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease is very high (>16 oz/day or 1/2 a litre/day). Having said that lowering ones dairy intake does have many benefits for ones health.

In addition, in our last post, we discussed the microbiome of the gut and how the bacteria there could be influencing Parkinson’s disease. It would be interesting to see whether follow-up studies of that particular study highlight any insecticide/pesticide interactions with the bacteria of the gut.

One last thing: The purpose of today’s post was not to scare people out of drinking milk, but merely to throw a curious observation out there for people to think about. It will be interesting to hear what people think about this, especially any observations based on their own experience.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from AndFarAway