In December last year, the Australian government gave official clearance for an American company – International Stem Cell Corporation – to conduct a stem cell based clinical trial at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Melbourne. This news was greeted with both excited hope from the Parkinson’s support community, but also concern from the Parkinson’s research community. In this post we will explore exactly what is going on.

Before reading on it may be wise for those unfamiliar with transplantation therapy in Parkinson’s disease to read our previous post about the topic, where we discuss the concept and the history of the field. Click here to read that post.

On the 14th December, the ‘Therapeutics Goods Administration’ (TGA) of Australia passed a regulatory submission from International Stem Cell Corporation (ISCO) for its wholly owned subsidiary, Cyto Therapeutics, to conduct a Phase I/II clinical trial of human stem cell-derived neural cells in patients with moderate to severe Parkinson’s disease. The hospital where the trial will be conducted -the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Melbourne – gave ethical approval in March this year for the trial to start and the company is now recruiting subjects.

What are the details of the trial?

Cyto Therapeutics (the subsidiary of ISCO) is planning a Phase I/IIa clinical study. This will evaluate the safety of the technique and provide some preliminary efficacy results. They are going to transplant human parthenogenetic stem cells-derived neural stem cells (ISC-hpNSC, for an explanation of this, please see below) into the brains of 12 patients with moderate to severe Parkinson’s disease. The study will be:

- an open-label (meaning that everyone knows what they are being treated with),

- single center (Royal Melbourne Hospital in Melbourne),

- uncontrolled (there wil be no sham/placebo treated group for comparison)

- an evaluation of three different doses of neural cells (from 30,000,000 to 70,000,000)

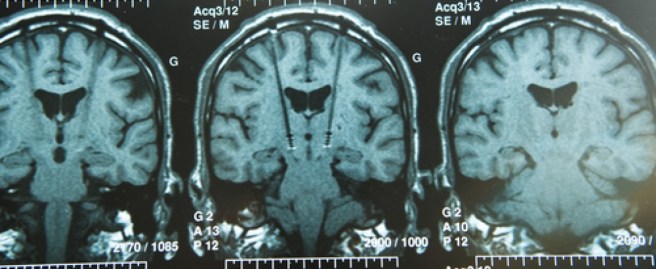

Following the transplantation procedure, the patients will be monitored for 12 months at specified intervals, to evaluate the safety and biologic activity of ISC-hpNSC. The monitoring process will include various neurological assessments and brain scans (PET) performed at baseline (as part of the initial screening assessment), and at 6 and 12 months post surgery.

What are ISC-hpNSCs?

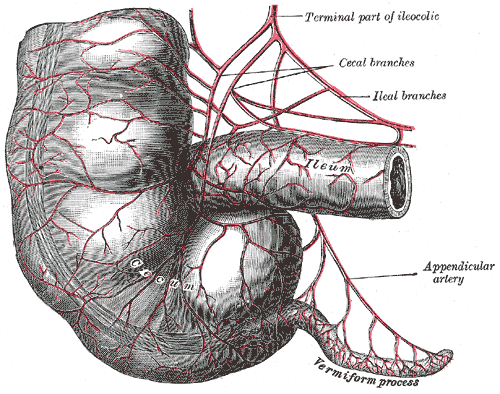

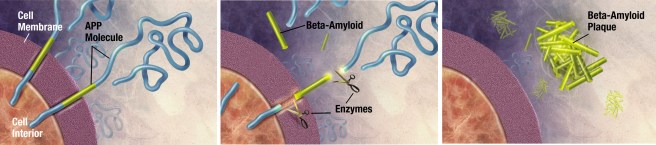

Transplantation of cells is theoretically a good way of replacing the tissue that is lost in neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson’s disease. Previous (and the current Transeuro) clinical trials have usually used tissue dissected from aborted fetuses to supply the dopamine neurons required for the transplantations. Obviously there are major ethic and moral issues/problems with this approach. There are also procedural issues with these trials (surgeries being cancelled as not enough tissue is available – tissue from at least three fetuses is required for each transplant).

Growing dopamine cells in petri dishes solves many of these problems. Millions of cells can be grown from a small number of starting cells, and there are no ethical issues regarding the fetal donors. As a result, there has been a major effort in the research community to push stem cells to become dopamine neurons that can be used in transplantation procedures.

Embryonic stem (ES) cells are of particular interest to researchers as a good starting point because the cells have the potential to become any type of cell in the body – they are ‘pluripotent’. ES cells can be encouraged using specific chemicals to become whatever kind of cell you want.

Embryonic stem cells in a petridish. Source: Wikipedia

Embryonic stem cells are derived from a fertilized egg cell. The egg cell will divide, to become two cells, then four, eight, sixteen, etc. Gradually, it enters a stage called the ‘blastocyst’. Inside the blastocyst is a group of cell that are called the ‘inner stem cell mass’, and it is these cells that can be collected and used as ES cells.

The process of attaining ES cells. Source: Howstuffworks

The human parthenogenetic stem cells-derived neural stem cells (hpNSC) that are going to be used in the Melbourne trial are slightly different. The hpNSCs come from an unfertilized egg – that is to say, no sperm cell is involved. The egg cell is chemically encouraged to start dividing and then becoming a blastocyst. This process is called ‘Parthenogenesis’, and it actually occurs naturally in some plants and animals. Proponents of the parthenogenic approach suggest that this is a more ethical way of generating ES cells as it does not result in the destruction of a viable organism.

What has been the response to the announced trial?

In general, the response from the Parkinson’s community has been very positive. The announcement of the trial was greeted by numerous support groups as a positive step forward (for some examples see Parkinson’s UK and the stem cellar blog).

So why then is the research community concerned about the study?

Basically the research community is concerned that this trial will be a repeat of the infamous Colorado/Columbia Trial and Tampa Bay trial back in the 1990s (two double-blind studies which initially suggested no positive effect from transplantation). Both of these studies have been criticised for methodological flaws, but more importantly longer term follow-ups with patients have suggested that the period of observation was too short (12-24 months post transplant), and longer term the transplants have had more positive outcomes – the cells simply required a longer period of time to fully develop into mature neurons. This last detail is important when considering the new trial in Australia – the trial will only follow the subjects for a period of one year.

There are concerns that the absence of paternal genes in parthenogenic stem cells has not been thoroughly investigated (remember that these cells only have the genes from the female egg cell). Paternal genes are believed to be more dominant that female genes during development (Click here for more on this). They may play an important role in the development of dopamine neurons, but this has never been investigated. As a result, researchers are asking if it is wise to move to the clinic before such issues are addressed.

There is also concerns that the preclinical research supporting the trial from the companies involved (ISCO and Cyto Therapeutic) is lacking. While there has been some research into the use of parthenogenic stem cells in models of Parkinson’s (Click here for an example), the research from the company involved in this trial is limited to just a couple of peer-reviewed publications.

The research community has begun expressing their concerns in editorial comments in various journals – the most recent being in the Journal of Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read that article – it is open access).

What preclinical research is supporting the trial?

As far as we here at the SoPD are aware (and we would be very pleased to be corrected on this), there is one research article on the company website dealing with the production of dopamine neurons, and that study did not deal with transplantation. It simply described the recipe from making dopamine neurons.

Title: Deriving dopaminergic neurons for clinical use. A practical approach.

Authors: Gonzalez R, Garitaonandia I, Abramihina T, Wambua GK, Ostrowska A, Brock M, Noskov A, Boscolo FS, Craw JS, Laurent LC, Snyder EY, Semechkin RA.

Journal: Sci Rep. 2013;3:1463.

PMID: 23492920 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

(One important caveat here – the research published in this study was conducted using both embryonic stem cells (WA-09 cell line) and hpNSCs, but there is no indication in the text as to which cells were used for each result or whether the different types of pluripotent cells gave the same results. The text is unclear on this)

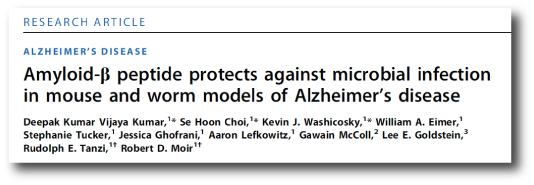

The company also published a study last year in which they transplanted the hpNSCs into both a rodent and primate model of Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Proof of concept studies exploring the safety and functional activity of human parthenogenetic-derived neural stem cells for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Gonzalez R, Garitaonandia I, Crain A, Poustovoitov M, Abramihina T, Noskov A, Jiang C, Morey R, Laurent LC, Elsworth JD, Snyder EY, Redmond DE Jr, Semechkin R.

Journal: Cell Transplant. 2015;24(4):681-90.

PMID: 25839189

The researchers in this study grew the hpNSCs in petridishes and pushed the cells towards becoming dopamine neurons, and then transplanted them into ten Parkinsonian rats and two Parkinsonian primates. Several months after transplantation, the researchers found the hpNSCs inside the brain and some of them had become dopamine neurons. There was, unfortunately, no indication as to how many of the hpNSCs survived the transplantation procedure. Nor any indication as to how many of them actually became dopamine neurons.

In addition, no behavioural data is presented in the study so there is no evidence that the cells had any functional effect. The researchers did measure the amount of dopamine in the brain, but those result suggested that there was only marginally more dopamine in the transplanted animals than the control animals (which had lesioned dopamine systems and saline injections rather than hpNSCs). Thus there is very evidence that the cells are functional inside the brain.

The researchers wrote in the report that “Most of the engrafted hpNSCs were dispersed from the graft site and remained undifferentiated”. This is not an ideal situation for a cell being transplanted into a particular region of the brain. Nor is it ideal for an undifferentiated cell to be going to the clinic.

And given that these two papers form the bulk of what has been published by the company with regards to their Parkinson’s disease work, researchers are concerned that the company is moving so aggressively to trial.

To be completely fair, ISCO has stated in a press release from April 2014, that their hpNSCs have been tested in 18 Parkinsonian primates. They suggested that those transplanted animals presented “significant improvement in the main Parkinson’s rating score”. Given that those results have never been made public, however, we are unclear as to what they actually mean (what is the “main Parkinson’s rating score”?).

We will follow the proceedings here at the Science of Parkinson’s with great interest.

FULL DISCLOSURE – The author of this blog is associated with research groups conducting the current Transeuro transplantation trials and the proposed G-Force embryonic stem cell trials planned for 2018. He has endeavoured to present an unbiased review of the current situation, but ultimately he is human and it is difficult to remain unbiased. He shares the concerns of the Parkinson’s scientific community that the research supporting the current Australian trial is lacking in its thoroughness.

It is important for all readers of this post to appreciate that cell transplantation for Parkinson’s disease is still experimental. Anyone declaring otherwise (or selling a procedure based on this approach) should not be trusted. While we appreciate the desperate desire of the Parkinson’s community to treat the disease ‘by any means possible’, bad or poor outcomes at the clinical trial stage for this technology could have serious consequences for the individuals receiving the procedure and negative ramifications for all future research in the stem cell transplantation area.

The header is of a scan of a brain after surgery. Source: Bionews-tx

UPDATE: 26/05/2016

ISCO has published further pre-clinical data this week regarding the cells that will be transplanted in their clinical trial. The data presented is from 18 transplanted monkeys:

Title: Neural Stem Cells Derived from Human Parthenogenetic Stem Cells Engraft and Promote Recovery in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Parkinson’s Disease.

Authors: Gonzalez R, Garitaonandia I, Poustovoitov M, Abramihina T, McEntire C, Culp B, Attwood J, Noskov A, Christiansen-Weber T, Khater M, Mora-Castilla S, To C, Crain A, Sherman G, Semechkin A, Laurent LC, Elsworth JD, Sladek J, Snyder EY, Jr DE, Kern RA.

Journal: Cell Transplant. 2016 May 20. [Epub ahead of print]

PMID: 27213850 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, 12 African Green monkeys with induced Parkinson’s disease (caused by the neurotoxin MPTP) were transplanted with hpNSCs in the midbrain and the striatum. 6 additional monkeys with induced Parkinson’s disease received saline as a control condition. Behavioural testing was conducted and the brains were inspected at 6 and 12 months.

Behaviourally, there was very little difference between the animals that were transplanted versus the control animals when they were compared at 12 months of age. This suggests that the transplant procedure is safe, but may not be having an effect at 12 months.

An inspection of the brain suggested that 10% of the transplanted cells survive to 12 months of age, and a few of them become dopamine neurons.

Some concerns regarding this new study:

Again the researchers have chosen to use saline injections as their control condition. It would be useful to see a comparison of hpNSCs with other types of transplanted cells (eg. fetal tissue or embryonic stem cells) – for a fairer comparison of efficiency.

The biochemical readings (the amount of dopamine in the brain) suggest an small increase in dopamine levels following transplantation, but only in one or two areas of the brain. Most of the analysed regions show no difference. And there is no comparison with a normal brain so it is difficult judge how truly restorative this procedure is. The increases that are observed may be minimal compared to what they should be in a normal brain.

Less than 2% of the transplanted cells became dopamine neurons. This is a bit of a worry given that we don’t know what the rest of the transplanted cells are doing. And the authors noted extensive migration of the cells into other areas of the brain. They reported this in their previous study. This is cause for real concern leading up to their clinical trial. The cells are being transplanted into a specific region of the brain for a specific reason (localised production of dopamine). If that dopamine is being produced in different areas of the brain, there may be unexpected side-effects from the procedure.

Another cause for concern leading up to the clinical trial is that the follow up period for the trial is only 12 months. Given that so little improvement has been seen in these monkeys over 12 months, how do the investigators expect to see significant changes in human over 12 months? The cells may well have an effect long term, but from the behavioural results presented in this new study, it is apparent that it will be extremely difficult to judge efficacy within 12 months.

Even when trying to view the study with an unbiased eye, it is difficult to agree with the researchers conclusion that the results “support the approval of the world’s first pluripotent stem cell based Phase I/IIa study for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease”. The lack of effect over 12 months and the migration of the transplanted cells suggest a serious rethink of the planned clinical study is required.