New research was published last week that suggests people with a high body mass index (or BMI) have a reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Really? How does that work?

In todays post we will discuss what body mass index is, review the results of the study and consider what this means for our understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

Lots of variety. Source: Pinsdaddy

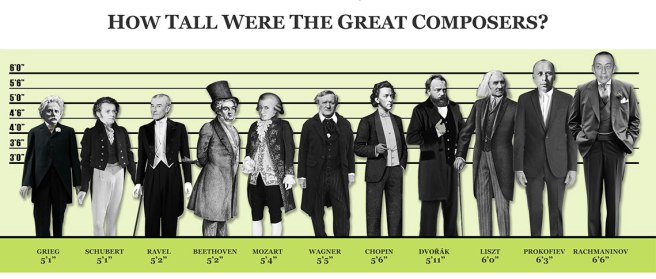

Humans being come in all sorts of different shapes and sizes.

Tall, short, skinny, obese….

The interesting aspect about some of these differences is the way they can make us vulnerable to certain diseases. For example, we have previously discussed how people with red hair have are 4 times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease than dark haired people (Click here to read that post, and here for a follow up post).

And now we have new research suggesting that your body mass may also influence your risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

What do you mean by body mass?

Your body mass is simply your weight.

It can be used to determine your approximate level of health by applying it to the body mass index.

And what is the body mass index?

The Body Mass Index. Source: Bioninja

The body mass index (or BMI) – also known as the Quetelet index – is a measure that is derived from the weight and height of an individual. Body mass index can be calculated according to the following formula:

That is simply your weight in kilograms divided by your height in metres squared.

For example, if you were a ridiculously tall (2.08 metres – 6 foot 8) Parkinson’s research scientist with bad hair and an approximate weight of 105kg (230 pounds), your BMI score would be 24.2 (time to put the laptop down and go for some walks). This was calculated by dividing 105 by 4.3 (2.08 x 2.08meters).

The authors BMI score. Source: NHS BMI Calculator

So what is the new research about BMI and Parkinson’s disease?

This is Dr Alastair Noyce:

He leads the PredictPD study (a really interesting longitudinal study to identify people at risk of Parkinson’s disease), which is based out of University College London. He is the lead author of the study.

And this is Prof Nick Wood:

He is the Galton Professor of Genetics, and the neuroscience programme director for Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. He has been at the forefront of many of the discoveries associated with the genetics of Parkinson’s disease, and he is the senior author of the study.

And this is the study:

Title: Estimating the causal influence of body mass index on risk of Parkinson disease: A Mendelian randomisation study.

Authors: Noyce AJ, Kia DA, Hemani G, Nicolas A, Price TR, De Pablo-Fernandez E, Haycock PC, Lewis PA, Foltynie T, Davey Smith G; International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium, Schrag A, Lees AJ, Hardy J, Singleton A, Nalls MA, Pearce N, Lawlor DA, Wood NW.

Journal: PLoS Med. 2017 Jun 13;14(6):e1002314.

PMID: 28609445 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

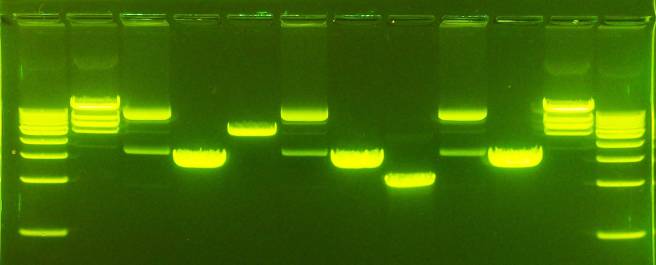

The researchers who published this study were interested in determining whether BMI and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease had any association (as you will see below there has previously been some disagreement about this). They began by collected data from the GIANT (Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits) study. The GIANT study was a huge consortium that was set up identify regions or variations within DNA that could impact body size and shape (such as height and measures of obesity). They didn’t find very many, but the dataset represents an enormous resource for researchers to use (information about 2,554,637 genetic variants from 339,224 individuals of European descent).

They next collected all of the most recent data about genetic variations associated with Parkinson’s disease (7,782,514 genetic variants from 13,708 cases of Parkinson’s disease and 95,282 individuals acting as controls, pooled from 15 independent datasets of individuals of European descent).

Using these two sets of data, the researchers were able to determine any relationship between genetic variants and BMI, and any relationship between those same genetic variants and Parkinson’s disease. Using this approach, they could then determine an estimated change in the risk of Parkinson’s disease per unit change in BMI score.

And when they conducted that analysis, the researchers found genetic variants expected to increase ones BMI score higher by 5 were actually associated with an 18 percent lower risk of Parkinson’s disease. That is to say, higher BMI scores were associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease – the odds ratio was 0.82 (1 being no difference) and the range of the odds was 0.69–0.98.

So does this mean I’m allowed to get fat? You know, to prevent Parkinson’s?

No. This would not be advisable.

One of the major limitations of this study (and many studies like it) is that individuals who have a higher BMI score have an increased risk of other diseases (heart disease, etc) which could result in an earlier death. They may die before they were eventually going to develop Parkinson’s disease. This ‘early death’ effect could result in individuals with a lower BMI being over-represented in the group of people diagnosed with Parkinson disease. This is called a “frailty effect”. In an attempt to reduce the possibility of a frailty effect in this study, the researchers conducted a further analysis (called ‘Frailty simulations’) to assess whether any associations they found were affected by mortality selection. This analysis suggested that the frailty effect could at least partially account for the association. That is to say, high BMI people dying earlier could partly explain the reduced frequency of Parkinson’s disease in that group.

In addition, there could also be subgroups within the low or high BMI population that could be affecting the data. The datasets used in the study lack of information about additional possible confounding variables. Confounding variables are factors that could influence the outcome of a study that haven’t been controlled for. In this study, for example, there was no information about smoking or coffee drinking, which have both been found to reduce risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Perhaps a subset of cases in the high BMI group were serious smokers and coffee drinkers?

So, don’t go changing to a high cholesterol diet just yet.

How does this result compare to previous research on BMI and Parkinson’s disease?

It is fair to say that there has been a lack of consensus in this field of research.

There is certainly evidence to support the results of this new research report. Earlier this year, for example, researchers in Korea reported that brain imaging of 400 people recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease suggested a lower BMI might be closely associated with low density of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, a region badly affected in Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more about that study).

But there is also some research that suggests that there no association between BMI and Parkinson’s disease, including this study which analysed data from multiple studies:

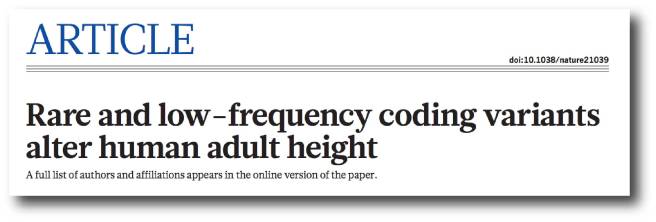

Title: Body Mass Index and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies.

Authors: Wang YL, Wang YT, Li JF, Zhang YZ, Yin HL, Han B.

Journal: PLoS One. 2015 Jun 29;10(6):e0131778.

PMID: 26121579 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

This study analysed data from 10 different studies and found no association between BMI and risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

And then there have been studies which have found the opposite effect of the new study – that is lower BMI scores are associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (Click here and here to read more about those studies).

These previous studies, however, have all been observational studies. The beauty of this new research report is that they applied genetic analysis to the question, which has helped them to better define and characterise their population of interest. It will be interesting to see if future studies taking a similar approach can provide some kind of consensus here.

What about BMI after someone is diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease?

Here the picture becomes a little bit clearer.

Weight loss can be a common feature of Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Association Between Change in Body Mass Index, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Scores, and Survival Among Persons With Parkinson Disease: Secondary Analysis of Longitudinal Data From NINDS Exploratory Trials in Parkinson Disease Long-term Study 1.

Authors: Wills AM, Pérez A, Wang J, Su X, Morgan J, Rajan SS, Leehey MA, Pontone GM, Chou KL, Umeh C, Mari Z, Boyd J; NINDS Exploratory Trials in Parkinson Disease (NET-PD) Investigators.

Journal: JAMA Neurol. 2016 Mar;73(3):321-8.

PMID: 26751506 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, 1673 people with Parkinson’s disease were recruited and followed over 3-6 years. Of these participants, 158 (9.4%) experienced weight loss (or a decrease in BMI), while 233 (13.9%) experienced weight gain (an increase in BMI). The weight loss group demonstrated an increase in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score (which indicates a worsening of Parkinsonian features), while the weight gain group actually exhibited a subtle decrease in their motor scores (an improvement in Parkinson’s features).

And this association between wait loss and worsening disease state is supported in a second study:

Title: Weight loss and impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Akbar U, He Y, Dai Y, Hack N, Malaty I, McFarland NR, Hess C, Schmidt P, Wu S, Okun MS.

Journal: PLoS One. 2015 May 4;10(5):e0124541.

PMID: 25938478 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study of 1718 people with Parkinson’s disease, the researchers found that more rapid weight loss was associated with higher number of co-morbidities (other medical complications), older age, higher L-dopa usage, and decreased health-related quality of life.

Thus weight loss is something for everyone to keep an eye on.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Weight loss can become apparent with an increase in dykinesias, but this is generally due to increased activity levels increasing levels of metabolism.

What does it all mean?

Using very large datasets, researchers in London have recently found that higher BMI scores are associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. This result is very interesting, even if much of the effect could be accounted for by the early mortality problem in the high BMI group.

Exactly how high BMI could infer neuroprotection or reduced chance of incurring the condition is still to be determined, and understanding the mechanisms of this effect could provide new understanding about the disease. It is ill advised, however, to consider that increasing ones BMI as a practical strategy for reducing the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

The banner for todays post was sourced from themoderngladiator

Acetylcysteine. Source:

Acetylcysteine. Source: