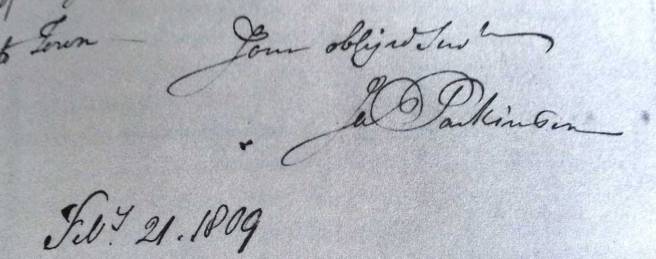

As part of Parkinson’s awareness month, and in observation of the 200 year anniversary of the first description of Parkinson’s disease, today we begin a four part set of posts looking at the man who made that first observation: James Parkinson.

Each week we will present various aspects about the man and his life.

Much of the material presented here has been replicated from our sister site Searching 4 James – a (much neglected) website celebrating the man and documenting the search for his likeness. To date, no portrait or image of the man has ever been found.

Source: Wellcome Images.

In her excellent book “James Parkinson, 1755-1824: From Apothecary to General Practitioner“, Shirley Roberts wrote that other sources have proposed that the man standing in the middle of the image above, talking to the villagers, is James Parkinson. The image appeared in James’ book ‘The Villager’s friend and physician’ (published in 1800), but (and I think you’ll agree) it does not give us much to work with.

Unfortunately Shirley Roberts made no reference to the sources of the proposal, but it is as close as we get to a likeness of the man, as he died before the first photographs were taken and there is no recorded painting of him.

Most people think of James Parkinson as a medical practitioner given his association with the disease that bears his name. But this singular association doesn’t really do the man credit. His contributions to medicine went well beyond the first description of ‘Parkinson’s disease’ – for example, James also gave the western world our first description of gout – a form of inflammatory arthritis that he and his father both suffered.

In addition, James was a ‘rockstar’ to the geological community, producing one of the most well regarded series of textbooks on the subject at the time. He was a political radical who wrote many pamphlets under the pseudonym “Old Hubert” and his associations with other radicals almost got him ‘transported’ (shipped out to the colonies). He was also a social reformist, calling for parliamentary reforms and universal suffrage. And his religious devotion made him a prominent figure within his church.

In short, he was a very interesting chap, who lived in (and had an impact on) interesting times.

THE WORLD OF JAMES

Before discussing the man himself, we must consider the world that James Parkinson was born into and the era he lived through. It provides us with the context within which we can fully appreciate the contributions that he made (including those beyond medicine).

James Parkinson was born on the 11th April 1755.

In the grand scale of things, the mid 1700’s was the peak of the little ice age, the middle of the age of enlightenment, and (critically) the start of the industrial revolution. The world was:

- Pre USA (1776)

- Pre French Revolution (1789)

- Pre public electricity supply (1881)

- Pre Napoleon (1769)

- Pre Darwin (1809)

In London, King George II was on the English throne (soon to be replaced by George III), and Westminster bridge had just been finished (1750). The population of the city was approx. 700,000, but most of them lived in terrible conditions.

A view of London (1750). Source: Historic Cities

James was born into a world where 74% of children born in London failed to reach the age of five. The medical world still practised humoral medicine (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood). Diseases were believed to be caused by an accumulation of “poisons” in the body, cured by bleeding, enemas, and sweating or blistering. The medical profession was:

- Pre Ed Jenner’s vaccine for smallpox (1796)

- Pre Rene Laennec’s stethoscope (1816)

- Pre nitrous oxide (1800) or ether anaesthesia (1846)

- Pre germ theory (Ignaz Semmelweis, 1847)

- Pre Joseph Lister’s anti-septic surgery (1863).

Amputations were by far the most frequent surgeries, but the survival rate of the procedure was only 40% (and remember, there was no anaesthesia).

James Parkinson was born at no. 1 Hoxton Square in the liberty of Hoxton in Shoreditch, Middlesex. He would live all but the last 2 years of his life at that address.

In 1755, Hoxton was simply a scattering of houses, orchards and market gardens that lay approximately half a mile from one of the north-east gates of the walls of London. During the 17-1800s, Hoxton Square was considered a very fashionable area and young James would have grown up surrounded by open, reasonably well to do areas.

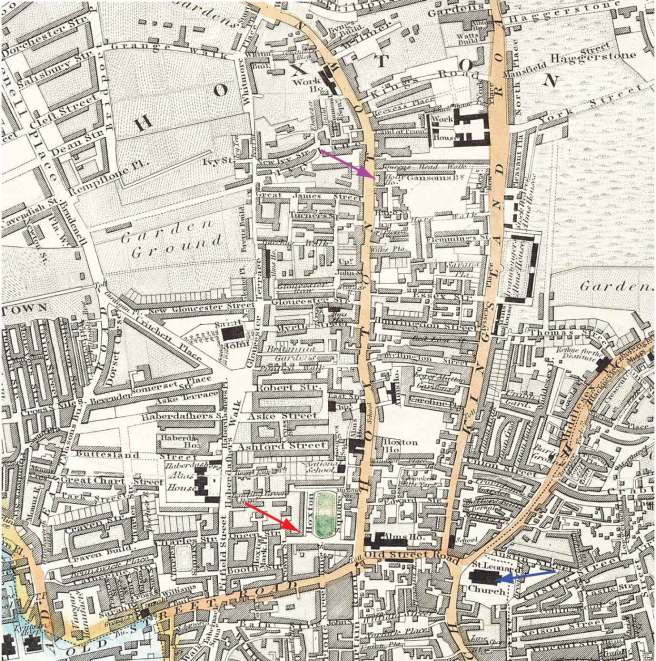

The maps below were made shortly before James was born, and it suggests open spaces, gardens, orchards and fields surrounding Hoxton.

London in 1746 (Shoreditch is indicated by the black square)

Source: John Roque’s Map

A map of Hoxton in 1746 – no 1. Hoxton Square (red arrow)

and St Leonard Church (blue arrow) are indicated.

James was born at the onset of the industrial revolution and with London prospering there was an enormous increase in the number of inhabitants. As more and more of London’s real estate became dedicated to business purposes, the inhabitants began spilling out into the surrounding areas. With transportation still limited to foot and horse, the people who worked in London needed to stay close to their place of employment, thus areas like Hoxton began to fill up rapidly. In 1788, there were 34,700 people living in Hoxton (in 5730 houses), which grew to 109,200 people in 1851 (in 15,433 houses).

Thus, during James’ life, Hoxton went through a radical transition. The large homes, orchards and gardens of his youth gave way to factories and over-crowding. And as a result, the ‘Parkinson and Son’ practise that he ran with his father (and later his own son) changed from serving a middle class clientele to dealing predominantly with the working class. With the prosperity of the time, there came a new trend of philanthropy, giving rise to the building of hospitals and mental asylums (‘madhouses’). James was the medical attendant for one of these madhouses, Holly House (Hoxton road, Hoxton).

The maps below were made in 1830 (shortly after James died – 1824) and indicate tremendous growth and expansion in London and the Hoxton area with the loss of much of the open spaces.

GREENWOOD MAP OF LONDON 1830 – Hoxton is indicated by the black square;

Tower of London (black arrow) and Westminster Abbey (red arrow) are also labelled – source: here

A map of Hoxton in 1830 – no 1. Hoxton Square (red arrow), St Leonard Church (blue arrow) and Holly House (Magenta arrow) are indicated.

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

James was baptised on the 29th of April 1755 in St Leonard’s church (Shoreditch) – the same church where he attended weekly services, got married, baptised his own children (and married some of them), and where he was eventually buried. The details of the baptism are recorded in the parish register, and read simply: James son of John and Mary Parkinson. Hoxton Square, Born 11th. Baptised 29th inst.

St Leonard’s church (1827) – Source

St Leonard’s church formed one of the key pillars of James’ life, and he could readily view the spire of the church one just block away from no.1 Hoxton Square.

The Parkinson family never owned the house at no. 1 Hoxton Square, which was owned by one Joshua Jenning. The building they lived in is gone now, but it was still standing in 1910 when Prof Leonard George Rowntree, a lecturer at Johns Hopkins Medical School (Baltimore), visited it and described it as:

“The house is a plain old three story building facing the east, on the northwest corner of Hoxton Square. Behind the main building and connected with it is a smaller two-story one with a central door opening into the little side street. This apparently was Parkinson’s office. Behind this again is another smaller building which may have served as a laboratory, as a library, or perhaps as a museum. Leading up to the deeply set, black, massive looking front door are a stone walk and deeply worn stone steps. The house is only a few feet back from the street and before it stands an old iron fence.

Uninteresting though the exterior is, upon entering this building one is impressed at the large size of the rooms and with the evidences of the prosperity of other days. We see in almost every room great carved open fire-places of elaborate design, and between some rooms large connecting arches. The deep panelling of walls and ceiling which was formerly so much in vogue is well preserved in some of the rooms on the second floor. One is surprised to find such an interesting interior behind such an uninviting exterior”

(Rowntree, 1912)

An image of no.1 Hoxton Square – Source

James was the eldest surviving child of John (an apothecary and surgeon) and Mary Parkinson. James had two sisters who survived to adulthood, Margaret Townley Parkinson (born 3rd August,1759) and Mary Sedgewood (born 11th January, 1763).

Little is known about the formative years of James Parkinsons. From his own writings, we know that he had a solid education in Latin and Greek as well as chemistry, biology and mathematics. James was fortunate to grow up in a ‘comfortable, cultured home’ with ‘a medical atmosphere’. But a thriving literary, scientific, and religious atmosphere also existed in Hoxton square. No fewer than fifteen residents of the Square are biographized in the Dictionary of National Biography – a distinction not shared by any other London Square from that time. Nothing is known about where James received his education. His name does not appear on the registry of scholars of the well known public schools of London, such as St Paul’s, the charterhouse, Christ’s Hospital, Merchants Taylors – all of which were within walking distance of Hoxton Square. Private home schooling was very popular during this time. James certainly did not attend Cambridge or Oxford University.

At age 16, James began his training to be an apothecary. In accordance with an antiquated Elizabethan Act of Parliament, in order to become a surgeon a young man had to serve an apprenticeship of seven years. James was apprenticed to his father, but 20 years later he wrote that “no apprenticeship should be advisable except to a hospital”. James was extremely critical of the traditional methods used in the teaching of medicine at the time:

“The first four or five years are almost entirely appropriated to the compounding of medicines; the art of which,with every habit of necessary exactness, might just as well be obtained in as many months. The remaining years of his apprenticeship bring with them the acquisition of the art of bleeding, of dressing a blister, and, for the completion of the climax – of exhibiting an enema” Parkinson, J. p32 (1800)

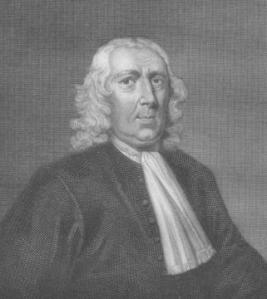

To further his training, James became one of the first medical students of the London Hospital Medical College (Whitechapel Road), founded by William Blizzard – surgeon of the Hospital. The college register records that he entered for training on Feb 20th 1776 when he was in his twentieth year. He was a ‘hospital pupil’ (or dresser) under Richard Grindall, FRS, at that time assistant surgeon. James remained for 6 months, but after this training he still felt ‘miserably ignorant’.

Richard Grindall (1716-1795) – by William Daniell, (21 Aug 1793) – Source

On 1st April 1784, James was examined and granted the grand diploma of the Company of Surgeons. He then joined his father in a practice, called “Parkinson and Son” (that practice was to last through 4 generations – approx. 80 years). Unfortunately, John Parkinson died only 6 years later, and James was left to manage the practice single-handedly. James was fortunate to take over his father’s prosperous practise as he noted that ‘a physician seldom obtains bread by his profession until he has no teeth left to eat it’. The clientele requiring the services of Parkinson and son, however, would change dramatically during James’s life. Parkinson’s and son’s evolved from a upper-middle class practise to an almost entirely working class practise by the time James passed on.

It says a great deal about the man that he did not move away from the community as it evolved (as many early inhabitants of Hoxton Square did).

On 21st May 1783, James married Mary Dale in St Leonard’s Church, by special license which was the custom of the upper and middle classes of that period. He was 25 and she was 23 years old. James’s friend Wakelin Welch Jr of Lympstone (Devon) acted as his best man (many years later, James’ book ‘Organic Remains of a Former World’ was dedicated to Welch).

According to the Family Pursuits website, Mary Dale (daughter of John Dale and Mary Hardy) was born 2nd September, 1757 in Shoreditch, Middlesex. Her family lived lived in Charles Square, Hoxton. Mary’s grandfather, Francis Dale (1650-1716), was an apothecary in Hoxton Old Town. He had three sons: Francis (also an apothecary), Thomas (1699-1750), and John (a silk merchant and Mary’s father). Her family not only had a medical history, but also geological. Mary’s grand uncle, Samuel Dale (1659-1739) was a keen botanist and one of the first to describe the fossils in the cliffs of Harwich (Essex).

Samuel Dale (1659-1739) – Source: The Essex Field Club

Thus the marriage was most likely a good fit for James. Mary Parkinson would live a long life, dying on 28 March 1838 of typhus fever (Gardner-Thorpe, 2013). Together with James, she had six children, key amongst them was John William Keys Parkinson (born 11th July, 1785) who apprenticed to his father and would later become the ‘Son’ in ‘Parkinson and Son’ (and ultimately John’s son James Keys Parkinson would follow in this process).

In the next post of this series, we will look at James’ early years as a physician and his foray into political radicalism.

Great post! Not only are you a scientist, you’re also a historian.

LikeLike

Thanks for the flattery Frank, but all of the hard work here was done by others:

Morris AD (1989). “James Parkinson: His Life and times’. Birkhauser

(the pick of the bunch!)

Roberts S (1997) James Parkinson, 1755-1824. From Apothecary to General Practitioner. The Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd. London.

Rowntree LG (1912) James Parkinson, London: The Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, 23, 33-45.

I am merely serving their labours on a different plate.

Simon

LikeLike

Could somebody link to Part ii, it seems to be missing and I’m dying of curiosity!

LikeLike