This is the kind of post that can really get someone in quite a bit of trouble.

Both the legal kind of trouble and the social media type of trouble.

Given the online excitement surrounding a particular video that appeared on the internet last week, however, we thought that it would be useful to have a look at the research that has been done on the medicinal use of Cannabis and Parkinson’s disease.

In addition, we will assess the legal status regarding the medicinal use of Cannabis (in the UK at least).

Cannabis being grown for medicinal use. Source: BusinessWire

This week a video appeared online that caused a bit of interest (and hopefully not too many arrests) in the Parkinson’s community.

Here is the video in question:

The video was posted by Ian Frizell, a 55 year old man with early onset Parkinson’s disease. He has recently had deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery to help control his tremors and he has also posted a video regarding that DBS surgery which people might find useful (Click here to see this).

In the video, Ian turns off his DBS stimulator and his tremors quickly become apparent. He then ‘self medicates’ with cannabis off camera and begins filming again some 20-30 minutes later to show the difference. The change with regards to his tremor are very clear and quite striking.

Here at the SoPD, we find the video very interesting, but we have two immediate questions:

- How is this reduction in tremors working?

- Would everyone experience the same effect?

We have previously seen many miraculous treatments online (such as coloured glasses controlling dyskinesias video from a few years ago) which have failed when tested under controlled conditions (the coloured glasses did not elicit any effect in the clinical setting – click here to read more). Some of these amazing results can simply be put down to the notorious placebo effect (we have previously discussed this in relation to Parkinson’s disease – click here to read the post), while others may vary on a person to person basis.

Thus, while we applaud Mr Frizell for sharing his finding with the Parkinson’s community, we are weary that the effect may not be applicable to everyone. For this reason, we have made a review of the scientific literature surrounding Cannabis and Parkinson’s disease.

But first:

What exactly is Cannabis?

Drawings of the Hemp plant, from Franz Eugen Köhler’s ‘Medizinal-Pflantzen’. Source: Wikipedia

Cannabis (also known as marijuana) is a family of flowering plants that can be found in three types: sativa, indica, and ruderalis. Cannabis is widely used as a recreational drug, behind only alcohol, caffeine and tobacco in its usage. It typically consumed as dried flower buds (marijuana), as a resin (hashish), or as various extracts which are collectively known as hashish oil.

While the three varieties of cannabis (sativa, indica, and ruderalis) may look very similar, pharmacologically they have very different properties. Cannabis sativa is often reported to cause a “spacey” or heady feeling, while Cannabis indica causes more of a “body high”. Cannabis ruderalis, by contrast, is less well used due to its low Tetrahydrocannabinol levels.

What is Tetrahydrocannabinol?

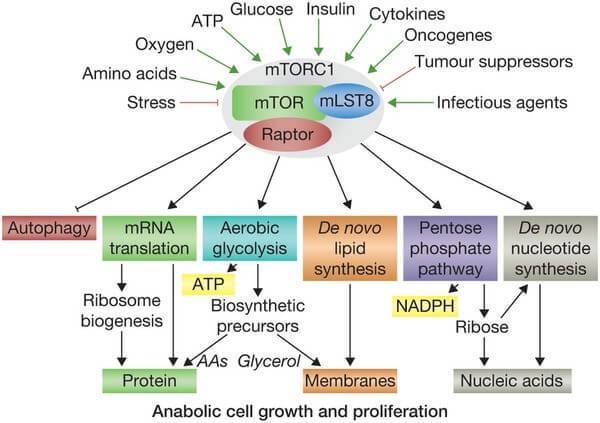

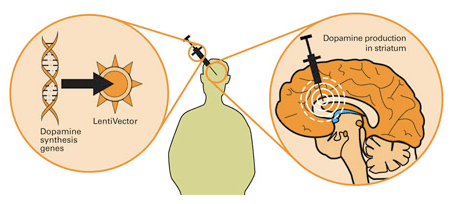

Tetrahydrocannabinol (or THC) is one of the principle psychoactive components in Cannabis. It a chemical that is believed to be a plant defensive mechanism against herbivores. THC is a cannabinoid, a type of chemical that attaches to the cannabinoid receptors in the body, and it is this pathway that many scientists are exploring for future neuroprotective therapies for Parkinson’s disease (For a good review on the potential cannabinoid-based therapies for Parkinson’s disease, click here).

A second type of cannabinoid is Cannabidiol (or CBD). CBD is considered to have a wider scope for potential medical applications. This is largely due to clinical reports suggesting reduced side effects compared to THC, in particular a lack of psychoactivity.

So what research has been done regarding Cannabis and Parkinson’s disease?

In 2004, a group of scientists in Prague (Czech Republic) were curious to determine cannabis use in people with Parkinson’s disease, so they conducted a study and published their results:

Title: Survey on cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease: subjective improvement of motor symptoms.

Authors: Venderová K, Růzicka E, Vorísek V, Visnovský P.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2004 Sep;19(9):1102-6.

PMID: 15372606

The researchers posted out 630 questionnaires to people with Parkinson’s disease in Prague. In total, 339 (53.8%) completed questionnaires were returned to them. Of these, 85 people reported Cannabis use (25.1% of returned questionnaires). They usually consumed it with meals (43.5%), and most of them were taking it once a day (52.9%).

After consuming cannabis, 39 responders (45.9%) described mild or substantial alleviation of their Parkinson’s symptoms in general, 26 (30.6%) improvement of rest tremor, 38 (44.7%) alleviation of rigidity (bradykinesia), 32 (37.7%) alleviation of muscle rigidity, and 12 (14.1%) improvement of L-dopa-induced dyskinesias.

Importantly, half of the people who consumed cannabis experience no effect on their Parkinson’s disease features, and four responders (4.7%) reported that cannabis actually worsened their symptoms. So while this survey suggested some positive effects of cannabis in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, it is apparent that the effect is different between people.

Additional surveys have been conducted around the world, with similar results (Click here to read more on this).

Have there been any clinical trials?

Yes, there have.

In the 1990s, there was a very small clinical study of cannabis use as a treatment option for Parkinson’s disease, and this study failed to demonstrate any positive outcome. In the study, none of the 5 people with Parkinson’s disease experienced any effect on their Parkinson’s motor features after a week of smoking cannabis (click here for more on this).

This study was followed up by a larger study:

Title: Cannabis for dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: a randomized double-blind crossover study.

Authors: Carroll CB, Bain PG, Teare L, Liu X, Joint C, Wroath C, Parkin SG, Fox P, Wright D, Hobart J, Zajicek JP.

Journal: Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;63(7):1245-50.

PMID: 15477546

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 19 people with Parkinson’s disease randomly received either oral cannabis extract or a placebo (twice daily) for 4 weeks. They then took no treatment for an intervening 2-week ‘washout’ period, before they were given the opposite treatment for 4 weeks (so if they received the cannabis extract during the first 4 weeks, they would be given the placebo during the second 4 weeks). In all cases, the participants and the researchers were ‘blind’ to (unaware of) which treatment was being given.

The results indicated that cannabis was well tolerated by all of the participants in the study, but that it had no pro- or anti-Parkinsonian actions. The researchers found no evidence for a treatment effect on levodopa-induced dyskinesia.

In addition to this study, there has been a recent double-blind clinical study of cannabidiol (CBD, mentioned above) in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial.

Authors: Chagas MH, Zuardi AW, Tumas V, Pena-Pereira MA, Sobreira ET, Bergamaschi MM, dos Santos AC, Teixeira AL, Hallak JE, Crippa JA.

Journal: J Psychopharmacol. 2014 Nov;28(11):1088-98.

PMID: 25237116

The Brazilian researchers who conducted the study took 21 people with Parkinson’s disease and assigned them to one of three groups which were treated with placebo, small dose of CBD (75 mg/day) or high dose of CBD (300 mg/day). They found that there was no positive effects by administering CBD to people with Parkinson’s disease, except in their self-reported measures on ‘quality of life’.

So what does all of this mean?

Firstly, let us be clear that we are not trying to discredit Mr Frizell or suggest that what he is experiencing is not a real effect. The video he has uploaded suggests that he is experiencing very positive benefits by consuming cannabis to help treat his tremors.

Having said that, based on the studies we have reviewed above we (here at the SoPD) have to conclude that the clinical evidence supporting the idea of cannabis as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease is inconclusive. There does appear to be some individuals (like Mr Frizell) who may experience some positive outcomes by consuming the drug, but there are also individuals for whom cannabis has no effect.

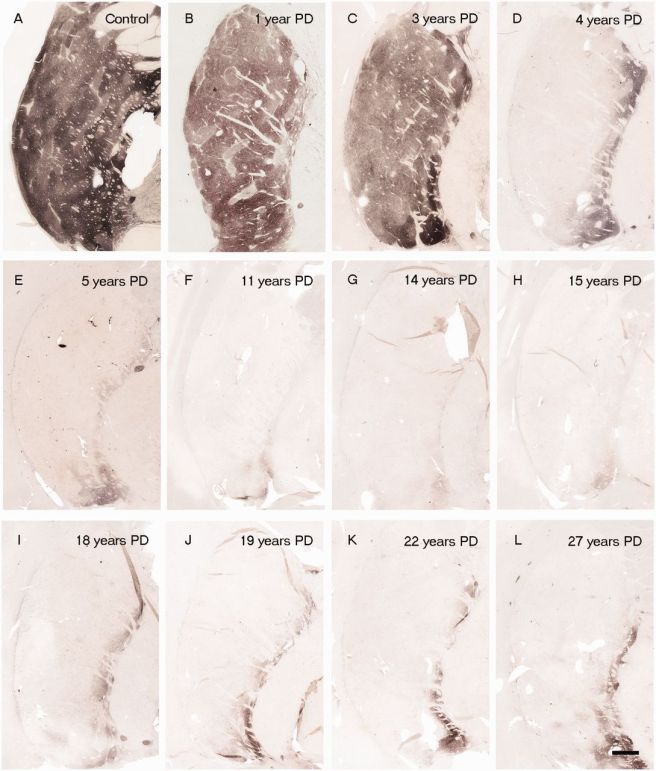

One of the reasons that cannabis may not be having an effect on everyone with Parkinson’s disease is that many people with Parkinson’s disease actually have a reduction in the cannabis receptors in the brain (click here for more on this). This reduction is believed to be due to the course of the disease. If there are less receptors for cannabis to bind to, there will be less effect of the drug.

Ok, but how might cannabis be having a positive effect on the guy in the video?

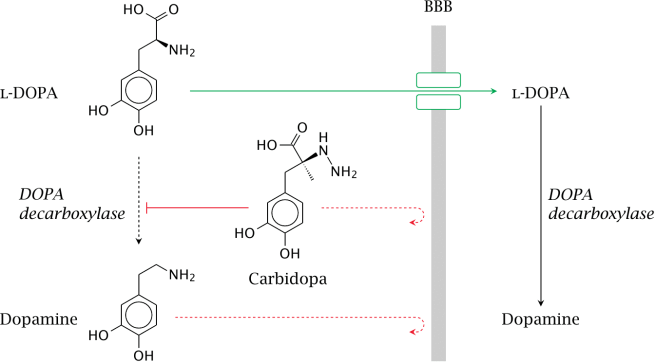

Cannabis is known to cause the release of dopamine in the brain – the chemical classically associated with Parkinson’s disease (Click here and here for more on this). Thus the positive effects that Mr Frizell is experiencing may simply be the result of more dopamine in his brain, similar to taking an L-dopa tablet. Whether enough dopamine is being released to explain the full effect is questionable, but this is still one possible explanation.

There could be questions regarding the long term benefits of Mr Frizell’s cannabis use, as long term users of cannabis generally have reduced levels of dopamine being released in the brain (Click here for more on this). Although the drug initially causes higher levels of dopamine to be released, over time (with long term use) the levels of dopamine in the brain gradually reduce.

I live in the UK. Is it legal for me to try using Cannabis for my Parkinson’s disease?

National status on Cannabis possession for medical purposes. Source: Wikipedia

The map above is incorrect, with regards to the UK at least (and may be incorrect for other regions as well).

According to the Home Office, it is illegal for UK residents to possess cannabis in any form (including medicinal).

Cannabis is illegal to possess, grow, distribute or sell in the UK without the appropriate licences. It is a Class B drug, which carries penalties for unlicensed dealing, unlicensed production and unlicensed trafficking of up to 14 years in prison (Source: Wikipedia; and if you don’t trust Wikipedia, here is the official UK Government website).

In 1999, a major House of Lords inquiry made the recommendation that cannabis should be made available with a doctor’s prescription. The government of the U.K., however, has not accepted the recommendations. Cannabis is not recognised as having any therapeutic value under the law in England and Wales.

Having said all of this, there has recently been an all-party group calls for the legalisation regarding cannabis for medicinal uses to be changed (click here for more on this). Whether this will happen is yet to be seen.

So the answer is “No, you are not allowed to use cannabis to treat your Parkinson’s disease”.

Except…

(And here is where things get a really grey)

There is a cannabis-based product – Sativex – which can be legally prescribed and supplied under special circumstances. Sativex is a mouth spray developed and manufactured by GW Pharmaceuticals in the UK. It is derived from two strains of cannabis leaf and flower, cultivated for their controlled proportions of the active compounds

THC and CBD.

In 2006, the Home Office licensed Sativex so that:

- Doctors could privately prescribe it (at their own risk)

- Pharmacists could possess and dispense it

- Named patients with a prescription could possess

In June 2010 the Medicines Healthcare Regulatory products Agency (MHRA) authorised Sativex as an extra treatment for patients with spasticity due to Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Importantly, doctors can also prescribe it for other things outside of the authorisation, but (again) this is at their own risk.

EDITORIAL NOTE: Given that possessing cannabis is illegal and that more research into the medicinal benefits of cannabis for Parkinson’s disease is required, we here are the SoPD can not endorse the use of cannabis for treating Parkinson’s disease.

While we are deeply sympathetic to the needs of many individuals within the Parkinson’s community and agree with a reconsideration of the laws surrounding the medicinal use of cannabis, we are also aware of the negative consequences of cannabis use (which can differ from person to person).

If a person with Parkinson’s disease is considering a change in their treatment regime for any reason, we must insist that they first discuss the matter with their trained medical physician before undertaking any changes.

The information provided here is strictly for educational purposes only.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from the IBTimes.