|

# # # # While disease modifying therapies are the ultimate goal for better treating Parkinson’s, research into therapeutic approaches that can provide better quality of life of people living with the condition are equally important. Neuroprosthetics are devices that use electrodes to interface with the nervous system and aim to restore function that has been lost. Cochlear implants are a good example of a neuroprosthetic that is improving people’s hearing. Recently, researchers in Switzerland have presented initial findings for a spinal cord neuroprosthesis that can help alleviate the locomotor deficits experienced in Parkinson’s. In today’s post, we will review the recent research and discuss what it could mean for the future of Parkinson’s treatment. # # # # |

The “Cairo toe”. Source: Smithsonianmag

The “Cairo toe”. Source: Smithsonianmag

The experts will tell you that the “Cairo toe” is special because it is flexible.

That is to say, it physically bends.

And this ‘bending’ property makes it rather unique among ancient prosthetics.

You see, when it was constructed (between 2,700 and 3,000 years ago), most artificial limbs were only cosmetic, rather than functional. And this difference is made particularly clear when one compares the “Cairo toe” with other early prosthetics of the same age that do not bend (Source):

An unwillingness to bend. Source: britishmuseum

An unwillingness to bend. Source: britishmuseum

So for its time, the “Cairo toe” must have been positively state of the art technology. It was one of the first functional prosthetics.

Great, but what does this have to do with Parkinson’s???

Well, we have come a long way since the “Cairo toe” with prosthetics, and recently researchers have been exploring a new kind of functional prosthetic – an implant – with the goal of improving quality of life for people with Parkinson’s.

What do you mean?

Before I answer this question, we need to discuss the spinal cord.

The spinal cord?

Yes, the spinal cord.

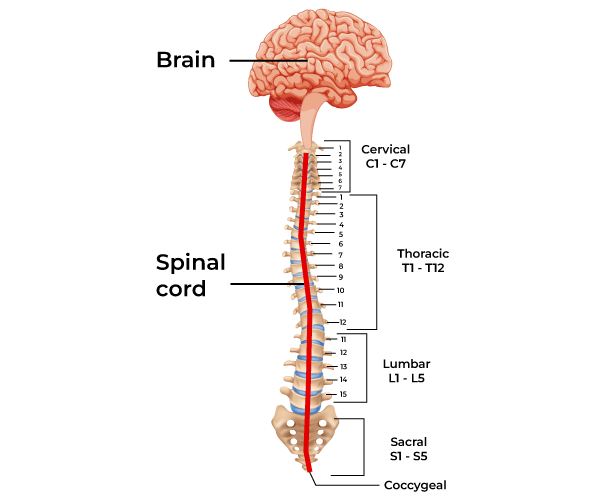

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular extension of the nervous tissue that stretches from the brainstem at the base of the brain down to the lower back. It is how the brain communicates with much of the peripheral body:

The spinal cord. Source: Geeksforgeeks

The spinal cord. Source: Geeksforgeeks

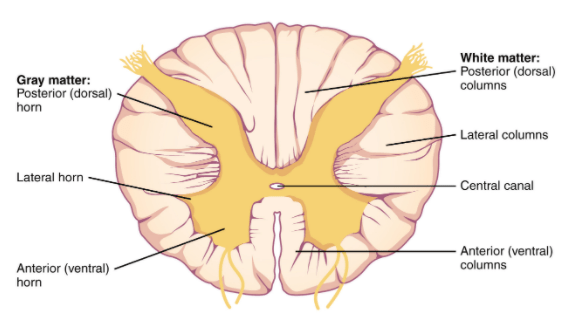

The spinal cord is divided into four different sections (the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions) and it consists primarily of two types of tissue: grey matter and white matter (grey matter being cell bodies and white matter involving a lot of myelinated neuronal fibers passing down through the spinal cord).

It is approximately 43-45 cm (18 inches) long in adults, with a diameter ranging from 13 mm (1⁄2 inch) in the cervical and lumbar regions to 6.4 mm (1⁄4 inch) in the thoracic area. The center of the spinal cord is hollow and contains a structure called central canal, through which cerebrospinal fluid flows (this helps to clear waste and provide nutrients).

A cross section of the spinal cord. Source: Vedantu

A cross section of the spinal cord. Source: Vedantu

The spinal cord is covered by a protective membrane called ‘meninges’. Note that the outer layer of meninges is referred to as the dura mater. The space between the surrounding vertebrae and the dura mater is called the epidural space (This it important in relation to the rest of the post). Administration of anaesthesia into the epidural space can cause a loss of sensation, by blocking the transmission of signals through nerve fibers in or near the spinal cord. As such, “epidurals” are commonly used for pain relief during childbirth and surgery.

A cross section of a vertebra Source: Pinterest

A cross section of a vertebra Source: Pinterest

The spinal cord and surrounding meninges are enclosed in a column of 33 vertebrae, connected by ligaments and intervertebral discs. Along the length of this structure, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves – one on each side of the vertebral column – which branch off from the spinal cord to interact with muscles and other organs around the body.

What happens to the spinal cord in Parkinson’s?

Interesting question. Initially, it was assumed that not much was happening in the spinal cord of Parkinson’s patients. All of the action was upstairs in the brain.

But postmortem examinations have now reported the presence of Lewy body pathology (a hall mark of the Parkinsonian brain) in the spinal cords of people with Parkinson’s (Click here read more about this).

These Lewy bodies have been more frequently found in the brainstem (such as the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve) than in the spinal cord, which researchers have interpreted as a sign that the disease process may begin in the brainstem and then progress upwards into the brain and downwards along the spinal cord (Click here, here and here to read more about this).

So the spinal cord does appear to be affected by Parkinson’s.

In addition, earlier this year, this report was published:

Title: Altered Spinal Cord Functional Connectivity Associated with Parkinson’s Disease Progression.

Title: Altered Spinal Cord Functional Connectivity Associated with Parkinson’s Disease Progression.

Authors: Landelle C, Dahlberg LS, Lungu O, Misic B, De Leener B, Doyon J.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2023 Apr;38(4):636-645.

PMID: 36802374 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers used a brain imaging procedure (resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging or fMRI) to measure spinal cord functional connectivity in a group of 70 people with Parkinson’s (and 24 unaffected control volunteers).

The Parkinson’s participants were divided into three groups based on the severity of their motor symptoms (24 individuals were considered ‘low’ severity, 22 were ‘mid’ severity, and 24 were designated ‘advanced’ in the motor symptom severity).

The results suggest that people with Parkinson’s have decreased spinal cord functional connectivity (compared to unaffected controls), and this was more apparent in the advanced severity group, suggesting that spinal cord dysfunction may be associated with disease progression. The results highlight the need to consider spinal cord dysfunction in the management and treatment of the condition.

OK, but what does this have to do with the prosthetic implant you mentioned above?

This is Professor Jocelyne Bloch and Professor Grégoire Courtine:

Source: Epfl

Source: Epfl

They are researchers at the NeuroX Institute at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, where they work on spinal cord connectivity. They have primarily been focused on spinal cord injury, and they made news media headlines in 2018, when they published this research report:

Title: Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury.

Title: Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury.

Authors: Wagner FB, Mignardot JB, Le Goff-Mignardot CG, Demesmaeker R, Komi S, Capogrosso M, Rowald A, Seáñez I, Caban M, Pirondini E, Vat M, McCracken LA, Heimgartner R, Fodor I, Watrin A, Seguin P, Paoles E, Van Den Keybus K, Eberle G, Schurch B, Pralong E, Becce F, Prior J, Buse N, Buschman R, Neufeld E, Kuster N, Carda S, von Zitzewitz J, Delattre V, Denison T, Lambert H, Minassian K, Bloch J, Courtine G.

Journal: Nature. 2018 Nov;563(7729):65-71.

PMID: 30382197

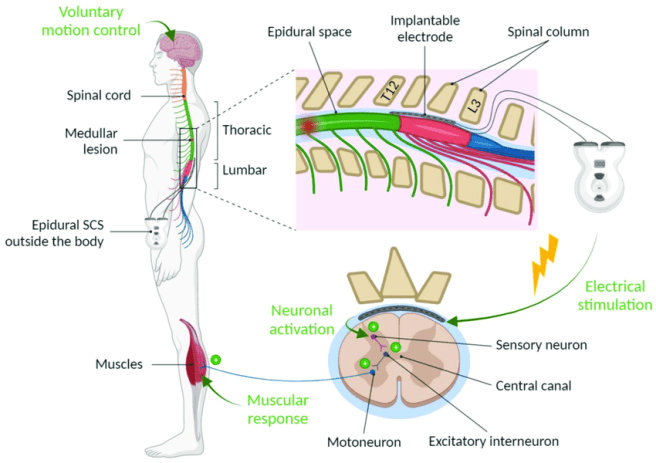

In this study, the researchers provided the results of the STIMO (STImulation Movement Overground) study. In their report, they presented the use of an implanted pulse generator to deliver trains of selective stimulation to the lumbosacral spinal cord (the lower region of the spine which controls leg muscles) in people who had suffered spinal cord injuries. This selective stimulation is called epidural electrical stimulation.

What is epidural electrical stimulation?

Epidural electrical stimulation was introduced in the 1970s to help alleviate abnormal muscle tightness due to prolonged muscle contraction in Multiple Sclerosis (Click here to read more about this). We spoke about the epidural space above in our description of the spinal cord. Epidural electrical stimulation involves a stimulating electrode, which has an array for different stimulating points:

A stimulating electrode. Source: Epiduralstimulationnow

A stimulating electrode. Source: Epiduralstimulationnow

This stimulating electrode is surgically placed in the epidural space so that the stimulating pads of the electrode are facing the spinal cord:

Source: Epiduralstimulationnow

Source: Epiduralstimulationnow

The electrode is then connected to a stimulator which can be programmed to provide very specific patterns of stimulation to the area of the spinal cord where the electrode has been placed.

Source: Researchgate

Source: Researchgate

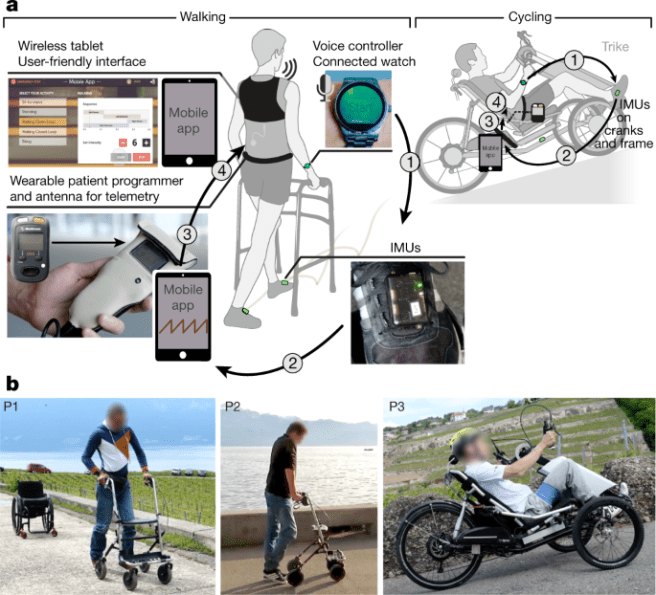

In their 2018 research report, Professors Bloch and Courtine used this patterned epidural electrical stimulation of the spinal cord surface to enable three people with spinal cord injury to walk across the laboratory with minimal assistance.

Importantly, recovery of functional leg movements during spatiotemporal epidural electrical stimulation allowed the three people to embrace new activities

of daily living (such as cycling). The researchers set the system up so that it could be turned on and off via a voice-activated wrist watch, and this allowed the individuals to have more options in term of their activities outside of the laboratory setting:

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

And these small achievements kinda grabbed the world’s attention:

This ability to stimulate walking and other activities in these three individuals was not perfect. It required wearable motion sensors to help initiate the preprogrammed stimulation sequences, and as a result the control of walking was not perceived as natural. In addition, the three individuals had limited options in terms of adapting the leg movements to changing terrain and other demands.

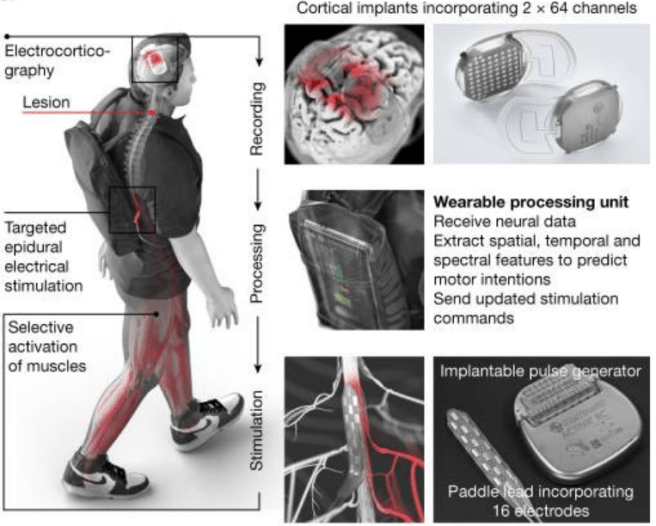

So in follow up research, the scientists developed a wireless, “digital bridge” between the brain and spinal cord to allow better control over the timing and strength of muscle activity, with the goal of restoring more natural and adaptive control of walking activity.

They published their results in this report:

Title: Walking naturally after spinal cord injury using a brain-spine interface.

Title: Walking naturally after spinal cord injury using a brain-spine interface.

Authors: Lorach H, Galvez A, Spagnolo V, Martel F, Karakas S, Intering N, Vat M, Faivre O, Harte C, Komi S, Ravier J, Collin T, Coquoz L, Sakr I, Baaklini E, Hernandez-Charpak SD, Dumont G, Buschman R, Buse N, Denison T, van Nes I, Asboth L, Watrin A, Struber L, Sauter-Starace F, Langar L, Auboiroux V, Carda S, Chabardes S, Aksenova T, Demesmaeker R, Charvet G, Bloch J, Courtine G.

Journal: Nature. 2023 Jun;618(7963):126-133.

PMID: 37225984 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

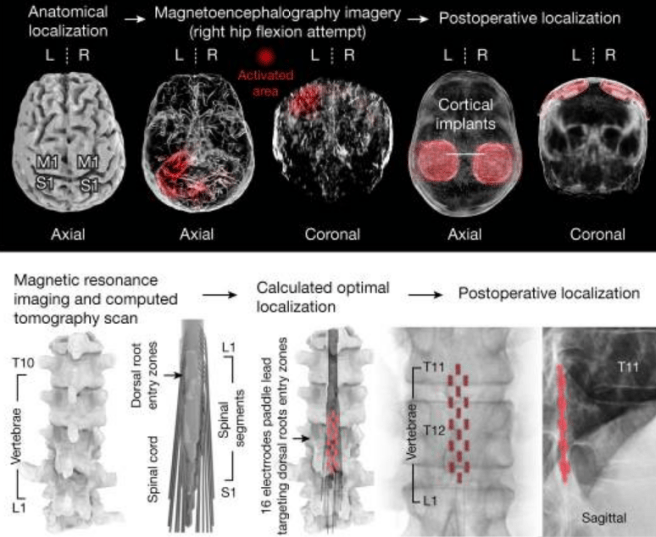

In this study, the scientists recruited a 38-year-old male who had sustained an incomplete spinal cord injury during a biking accident ten years before (the injurry was in C5/C6 of the cervical region of the spine). They developed a cortical recording device which was implanted in this individuals head above the motor cortex:

Source: PMC

These recording devices collected brain activity and fed it to a wearable processing unit that the individual wore on their back, and this sent instructions to an implanted stimulator and electrode array which sat on the lumbar spinal cord:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

One particularly intriguing detail about this research is that the “neurorehabilitation” associated with the epidural electrical stimulation approach appears to have improved neurological recovery. In this study, the participant regained the ability to walk with crutches even when the stimulation was switched off.

And again, this garnered much attention from the media:

For those interested in reading more about this, click here for an excellent review on the topic.

This is great for people with spinal cord injury, but what does it have to do with Parkinson’s?

Well, the same research group led by Professors Jocelyne Bloch and Grégoire Courtine have turned their attention to Parkinson’s, and very recently they published this report:

Title: A spinal cord neuroprosthesis for locomotor deficits due to Parkinson’s disease.

Title: A spinal cord neuroprosthesis for locomotor deficits due to Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Milekovic T, Moraud EM, Macellari N, Moerman C, Raschellà F, Sun S, Perich MG, Varescon C, Demesmaeker R, Bruel A, Bole-Feysot LN, Schiavone G, Pirondini E, YunLong C, Hao L, Galvez A, Hernandez-Charpak SD, Dumont G, Ravier J, Le Goff-Mignardot CG, Mignardot JB, Carparelli G, Harte C, Hankov N, Aureli V, Watrin A, Lambert H, Borton D, Laurens J, Vollenweider I, Borgognon S, Bourre F, Goillandeau M, Ko WKD, Petit L, Li Q, Buschman R, Buse N, Yaroshinsky M, Ledoux JB, Becce F, Jimenez MC, Bally JF, Denison T, Guehl D, Ijspeert A, Capogrosso M, Squair JW, Asboth L, Starr PA, Wang DD, Lacour SP, Micera S, Qin C, Bloch J, Bezard E, Courtine G.

Journal: Nat Med. 2023 Nov 6. Online ahead of print.

PMID: 37932548

In this study, the researchers began by recording the walking of nine monkeys before and after they were treated with a chemical called MPTP. This is a neurotoxin that specifically kills dopamine neurons in the brain and has been used as for many years as a means of modelling late stage Parkinson’s. By recording these primates, the researchers were able to capture the key features of impaired gait.

They next recorded the walking pattern of 25 people with Parkinson’s, as well as nine healthy age-matched ‘control’ individuals. Their analysis demonstrated that at a basic level, the MPTP-treated monkeys share many of the walking impairments and balance problems that were observed in the people with Parkinson’s

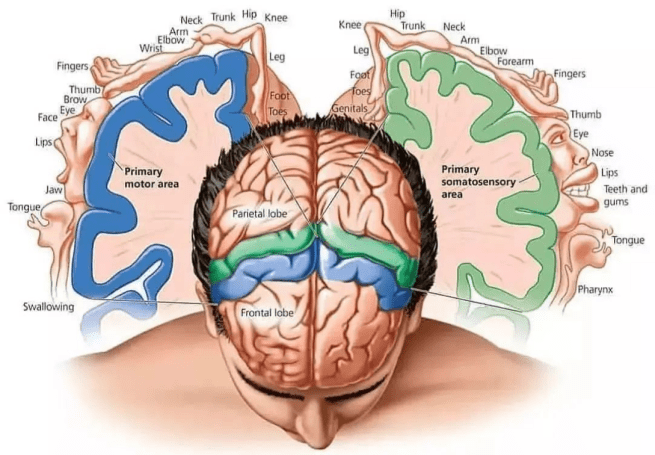

The next step (excuse the pun) involved determining the natural sequence of activation of leg motor neurons in healthy monkeys, and comparing this with how the MPTP treatment may affect that activation. The motor neurons that control the legs are located in the primary motor cortex of the brain and so the researchers developed a head-mounted system that enabled wireless recordings of electrical activity of those neurons.

The location of the primary motor cortex in the brain (blue region). Source: Instagram

The location of the primary motor cortex in the brain (blue region). Source: Instagram

The primary motor cortex is a strip of the cerebral cortex that cuts across the top of the brain (see the blue strip in the image above). The neurons involved in the activity of the legs are right in the central midline of the cortex.

At the same time as recording the motor neurons in the brain, they also measured the electrical activity of the leg muscles to help associate the brain recordings with the initiation of leg movement. The resulting map of leg motor neuron activation patterns – both geographically in the brain and temporally across time – revealed that walking basically involves the sequential active of six hotspots that the researchers could work with.

With all of this information, the researchers next took three primates that had been treated with MPTP and had developed severe gait abnormalities, and they surgically two microelectrode arrays in the left and right motor cortex, along with two stimulating electrode arrays over the spinal cord. The idea was to acquire the neural signals from the motor cortex and send augmented sequences of epidural electrical stimulation bursts to the stimulating array in the spinal cord to activate the six hotspots in order to facilitate walking.

They found that this brain controlled epidural electrical stimulation immediately improved gait impairments and balance problems in the three primates. They also found that the brain-controlled neuroprosthesis complements deep brain stimulation therapy.

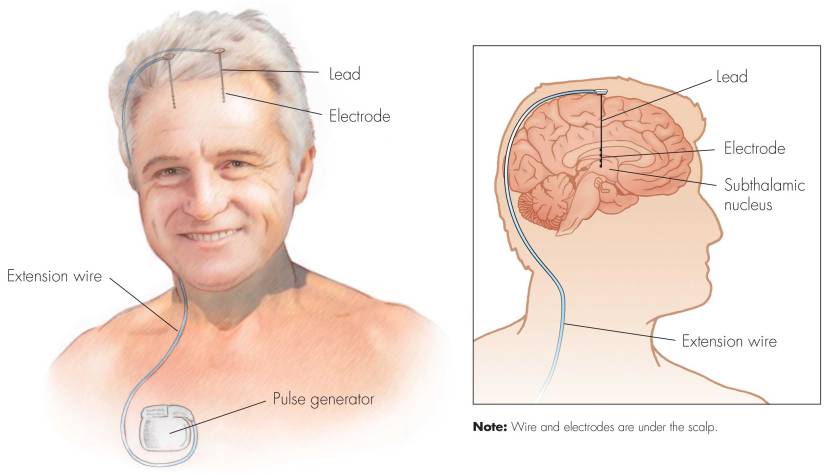

Remind me: What is deep brain stimulation therapy?

Deep brain stimulation (or DBS) is a treatment method that involves embedding electrodes into the brain to help modulate the brain activity involved in movement.

First introduced in 1987, deep brain stimulation consists of three components: the pulse generator, an extension wire, and the leads (which the electrodes are attached to). All of these components are implanted inside the body. The system is turned on, programmed and turned off remotely.

Source: Ucdmc

The electrodes that are implanted deep in the brain are tiny, and the very tip of them has small metal plates (each less than a mm in width) which provide the pulses that will help mediate the activity in the brain.

DBS electrode tip. Source: Oxford

The electrode extends up into the leads (or extension wire) which continue up and out of the brain, across the top of the skull, down the neck and to the pulse generator which is generally located on the chest.

Xray image demonstrating the leads. Source: Fineartamerica

DBS reduces inhibition inside specific structures in the brain, which allows individuals with Parkinson’s to move more freely (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on DBS).

To assess if brain controlled epidural electrical stimulation could augment DBS, the research team in Switzerland tested their neuroprosthesis system in parallel to DBS in primates. They found that the two systems complemented each other, providing synergistic improvements in gait and walking speed.

Interesting. Have they tested this in people with Parkinson’s?

Yes, they have.

The researchers recruited a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of Parkinson’s to take part in the STIMO-PARK clinical trial. He had previously been implanted with DBS and had been on stable dopaminergic replacement therapy for a long time, but he still suffered from severe locomotor deficits that resulted in 2–3 falls per day.

Following implantation of the neuroprosthesis, the researchers assessed the Parkinson’s motor symptoms of the gentleman using the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Part III. This is 0-132 point clinician-based rating scale (132 being the worst possible score). They found that when the DBS system and the neuroprosthesis were both switched off, the patient had a UPDRS Part III score of 65 (scores of 59 and above are considered severe).

When they turned on the DBS system, his UPDRS III score improved to 29. Interestingly, when the neuroprosthesis was also turned on, his score improved further to 24.

The gentleman also suffered from frequent freezing-of-gait episodes, which occurred when he was turning and also passing through narrow gaps, like doorways. This is a common feature of Parkinson’s, but when the neuroprosthesis was turned on, the researchers reported that episodes of freezing of gait “nearly vanished, both with and without DBS“.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis for nearly 2 years, and it has enabled him to “enjoy recreational walks in nature over several kilometers without any additional assistance“. He typically has the system switched on for about 8 hours per day, only turning it off when sitting for long periods of time or sleeping.

And again, this research has drawn significant media attention:

Also see:

Are there any additional clinical trials exploring this new technology in Parkinson’s?

Yes.

There is the SPARKL clinical trial which is currently ongoing. It involves 6 people with advanced Parkinson’s and it is assessing the safety and efficacy of the neuroprosthesis technology. The study is taking place at the Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland and it will involve 4 years of assessment for each of the participants.

Great. So what does it all mean?

In today’s post, we have discussed how researchers in Switzerland have developed a digital bridge between the brain and the spinal cord to support individuals with spinal cord injuries and other neurological conditions that affect gait and movement. While still in its infancy and as invasive as the technology currently is, it is encouraging to see this kind of research is already offering improvements in quality of life for those brave enough to take part in the studies.

As with lots of the research discussed on this website, it will be really interesting to see how this technology evolves going forward and how it integrates with advancements in other therapeutic approaches, such as adaptive DBS or continuous delivery levodopa (produodopa). It is commendable that the researchers involved have already considered this and introduced the combination of DBS and epidural electrical stimulation into their assessments.

In the end, I am left wondering how future archeologists will look back upon the Swiss neuroprosthesis and how the gap between it and the “Cairo toe” will be perceived. Hopefully the Swiss prosthetic will be viewed as a successful part of the broader history of research that ultimately led to curative therapies for Parkinson’s.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from epfl.

Fascinating, thank you.

LikeLike

You are welcome Ben. Glad you found it interesting.

LikeLike

Thanks Simon. Happy to see your posts again. Hope you’re doing well.

TomR

LikeLike