|

# # # # Mitochondria are tiny structures inside of cells that function as power stations, providing cells with energy to conduct all of their functions. When mitochondria become dysfunctional, they can put a lot of stress on cells, potentially leading to cellular death. A common feature of Parkinson’s is mitochondrial dysfunction. Evolution has provided various methods of removing dysfunctional mitochondria. One of these processes is called mitophagy. One biotech company leading the charge in the field of enhancing mitophagy is Mission Therapeutics, and they have very recently published some interesting pre-clinical data on their lead clinical candidate. In today’s post, we will look at what mitophagy is, how Mission Therapeutics is attempting to enhance it, and what their newly published data reports. # # # # |

Sir Steve. Source: bioc

Sir Steve. Source: bioc

Prof Sir Steve Jackson is a bit of a legend in research circles at the University of Cambridge.

In 1997, he founded a biotech called KuDOS Pharmaceuticals which developed a successful PARP1 inhibitor (Olaparib) for cancer. That company was acquired in 2005 by AstraZeneca who jointly (with Merck) owns and developed Olaparib (also known as Lynparza – and it may be of interest to readers that PARP1 inhibitors are now being considered for Parkinson’s – click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic).

Not to sit on his laurels, Sir Steve then founded another biotech firm in 2011, called Mission Therapeutics. This company was focused on agents targeting deubiquitinating (DUB) enzymes (more on them in a moment).

Source: Mission

Source: Mission

In November 2018, the large pharmaceutical company AbbVie made some waves by signing a drug discovery and development deal with the 7-year old Mission Therapeutics, to explore deubiquitylating enzymes (or DUBs) in the context of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (Source).

And then in August of 2021, the companies signed another deal (Source), which involved AbbVie announcing progression of two selected DUB targets into the next phase of research.

Very recently, Mission Therapeutics has published research on its own research into Parkinson’s and the results are VERY interesting.

What did they find?

Here is the report in question:

Title: Knockout or inhibition of USP30 protects dopaminergic neurons in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model.

Title: Knockout or inhibition of USP30 protects dopaminergic neurons in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model.

Authors: Fang TZ, Sun Y, Pearce AC, Eleuteri S, Kemp M, Luckhurst CA, Williams R, Mills R, Almond S, Burzynski L, Márkus NM, Lelliott CJ, Karp NA, Adams DJ, Jackson SP, Zhao JF, Ganley IG, Thompson PW, Balmus G, Simon DK.

Journal: Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 13;14(1):7295.

PMID: 37957154 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The study can be broken down into two parts: First, the researchers investigate and characterise what happens when a specific protein is removed from an organism, and second, they present the development of a novel agent that they are targeting towards Parkinson’s.

Sounds interesting. What is the protein they removed?

The protein is called ubiquitin-specific protease 30 (or just USP30).

And it functions as a deubiquitinating enzyme.

What is a deubiquitinating enzyme?

Deubiquitinating (or DUB) enzymes are a very large group of proteins (there are 102 in humans) that are critically involved in a process that is called ubiquitination.

And what is ubiquitination?

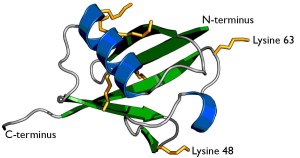

Ubiquitination is the process of adding a small protein called ubiquitin to other proteins.

The process of ubiquitination can affect proteins in many different ways. Ubiquitin can:

- Label them for removal/disposal

- Alter their location within a cell

- Change their level of activity

- Promote/prevent interactions with other proteins

Ubiquitin is a marvelous little protein that – as the name suggests – is ‘ubiquitous’ in all cells, and as indicated above it affects all aspects of cell biology.

The structure of ubiquitin. Source: Wikipedia

One of the most studied process associated with ubiquitination is the labelling of particular proteins for disposal.

There are primarily two ways that cells dispose/recycle damaged or old stuff. And both of them involve ubiquitination.

The first is called the Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway.

Source: 2bscientific

A protein labelled with a lot of ubiquitin will be identified and sent off for disposal and be broken down in a structure called the proteasome.

A second process by which cells dispose of rubbish is called autophagy.

Autophagy (from the Ancient Greek αὐτόφαγος autóphagos, meaning “self-devouring”) is an absolutely essential function in a cell. Without autophagy, old proteins would pile up making the cell sick and eventually causing it to die. Through the process of autophagy, the cell can break down the old protein, clearing the way for fresh new proteins to do their job.

The process of autophagy. Source: Wormbook

Waste material inside a cell is collected in membranes that form sacs (called vesicles). These vesicles then bind to another sac (called a lysosome) which contains enzymes that will breakdown and degrade the waste material – the same way enzymes in your washing powder break down muck on your dirty clothes). The degraded waste material can then be recycled or disposed of by spitting it out of the cell.

There are different types of autophagy, and one is thought to be rather critical in the case of Parkinson’s.

It is called mitophagy and it involves the disposal of old or dysfunctional mitochondria.

What is mitophagy?

Mitochondria – you may recall from previous SoPD posts – are the power stations of each cell. They help to keep the lights on. Without them, the party is over and the cell dies.

Mitochondria and their location in the cell. Source: NCBI

You may remember from high school biology class that mitochondria are tiny bean-shaped objects within the cell. They convert nutrients from food into Adenosine Triphosphate (or ATP). ATP is the fuel which cells run on. Given their critical role in energy supply, mitochondria are plentiful (some cells have thousands) and highly organised within the cell, being moved around to wherever they are needed.

Like you, me and all other things in life, mitochondria have a use-by date.

As mitochondria get old and worn out (or damaged) with time, the cell will dispose of them via mitophagy.

There are two Parkinson’s-associated proteins that play important roles in mitophagy. They are named PARKIN and PINK1.

PINK1 acts like a kind of handle on the surface of mitochondria. In normal, healthy mitochondria, the PINK1 protein attaches to the surface of mitochondria and it is slowly absorbed until it completely disappears from the surface and is degraded. In unhealthy mitochondria, however, this process is inhibited and PINK1 starts to accumulate on the outer surface of the mitochondria.

If PINK1 a handle on the surface of the mitochondria, then PARKIN is the flag that likes to hold onto the PINK1 handle. While exposed on the surface of a mitochondrion (singular) PINK1 starts grabbing the PARKIN protein. This pairing activates PARKIN which starts attaching ubiquitin to molecules on the surface of the mitochondrion. When enough ubiquitination has occurred and there is a build up of ubiquitin on the surface of the mitochondrion, the cell is alert to the fact that this particular mitochondrion is not healthy and needs to be removed.

Pink1 and Parkin in normal (right) and unhealthy (left) situations. Source: Hindawi

Think of both autophagy and the proteosome pathway as the waste disposal/recycling mechanisms of the cell.

But understand that ubiquitin and ubiquitination are critical to both processes.

How are deubiquitinating enzymes involved in these process?

The biological world is all about balance.

For every enzyme, like PARKIN that likes to attach ubiquitin to something, there needs to be an enzyme that does the opposite (removes ubiquitin from stuff).

And this is – as the label on the can suggests – what ‘deubiquitinating’ enzymes do. They are actively involved with the removal of ubiquitin from proteins. As illustrated in the image below deubiquitinating enzymes (Deub; labelled in yellow) remove ubiquitin (Ub) from proteins. But if they don’t take enough off, the protein is sent off for disposal.

Source: Wikipedia

Thus, while there are some enzymes rapidly attaching ubiquitin to proteins, there are equally enzymes removing it. This gives us balance. Without deubiquitinating enzymes, ubiquitin attaching enzymes would simply run wild.

This balance also means that the difference between a protein inside the cell being allowed to continue functioning or being sent off for disposal depends on how much ubiquitin is attached to it.

Ok, but why would researchers be interested in deubiquitinating enzymes?

A while back, some clever researchers realised that by blocking or enhancing specific deubiquitinating enzymes, one could potentially tip the balance in favour of either reducing or increasing levels of a particular protein.

For example, if there is a particular deubiquitinating enzyme that removes ubiquitin from a protein like Parkinson’s-associated Alpha Synuclein, one could design a drug (a DUB inhibitor) targeting that deubiquitinating enzyme which would block it from removing ubiquitin from alpha synuclein. This would result in more ubiquitin remaining on alpha synuclein protein, thus increasing the chances of its removal and disposal.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) inhibitors represent a method of increasing the removal of a particular protein from a cell.

For a good review on the topic of deubiquitinating enzyme – Click here.

Interesting idea. Are there any associations between deubiquitinating enzymes and Parkinson’s?

Yes, there are.

In fact, it is remarkable to note that of the 23 PARK genes (genes associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s), two of them encode (or provide the instructions for making) DUB enzymes.

Those two genes are:

- Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (also known as PARK5) – genetic variations in this region of DNA result in a higher risk of classical late-onset Parkinson’s. UCHL1 is probably the most studied DUB, because it has associations with both neurodegenerative conditions and the progression of malignancies. UCHL1 is extremely abundant in all neurons (remarkably it alone accounts for 1-2% of total brain protein), and it is also found in Lewy bodies (Source). Curiously, one genetic mutation in this gene is associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s (Source), while another genetic variant in this gene has been proposed to be associated with a reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s (Source).

- Ubiquitin specific peptidase 24 (also known as PARK10) – genetic variations in this region of DNA also result in a higher risk of classical late onset Parkinson’s disease. This enzyme is known to remove ubiquitin from damage-specific DNA-binding protein 2 (DDB2). By removing the ubiquitin from DDB2, the enzyme increases the stability of DDB2. DDB2 is involved in DNA damage recognition, which means that an unstable version of DDB2 could result in increased risk of high levels of damaged DNA.

Interesting. So, going back to the Mission Therapeutics report. What were they doing with DUBs?

They were looking at a DUB called ubiquitin-specific protease 30 (USP30).

And what does USP30 do?

USP30 is present on mitochondria and it antagonizes mitophagy that is driven by PARKIN and PINK1. This means that while PARKIN and PINK1 might be trying really hard to ubiqutinate a mitochondrion for waste disposal, USP30 will be actively deubiquitinating the mitochondrion – preventing it’s disposal.

Has anyone ever looked at USP30 in the context of Parkinson’s before?

Yes, there has been some pre-clinical research. Such as this report:

Title: The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy.

Authors: Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, Reichelt M, Bakalarski CE, Song Q, Foreman O, Kirkpatrick DS, Sheng M.

Journal: Nature. 2014 Jun 19;510(7505):370-375.

PMID: 24896179

In this study, the researchers found that by artificially increasing levels of the deubiquitinating enzyme ‘USP30’ in cells, the ubiquitin attached by PARKIN onto damaged mitochondria was rapidly removed. This effectively blocked the ability of PARKIN to cause mitophagy to occur. When the investigators conducted the reverse experiment – reducing USP30 activity – they found enhanced levels of mitochondrial degradation in neurons.

Next, the researchers reduced USP30 levels in flies treated with a neurotoxin (paraquat – a toxin that kills dopamine neurons by stressing mitochondria). They found that lowering USP30 levels reduced the loss of dopamine neuron, rescued motor function, and improved overall survival (compared to neurotoxin-only treated flies). These results suggested to the researchers that USP30 inhibition could be potentially beneficial for Parkinson’s.

These results have been replicated by independent research groups (Click here and here to read that research), and supported by other research looking at USP30 and PARKIN (Click here and here to read more about this)

Ok, so what does the Mission Therapeutics report say?

This is the report in question:

Title: Knockout or inhibition of USP30 protects dopaminergic neurons in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model.

Title: Knockout or inhibition of USP30 protects dopaminergic neurons in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model.

Authors: Fang TZ, Sun Y, Pearce AC, Eleuteri S, Kemp M, Luckhurst CA, Williams R, Mills R, Almond S, Burzynski L, Márkus NM, Lelliott CJ, Karp NA, Adams DJ, Jackson SP, Zhao JF, Ganley IG, Thompson PW, Balmus G, Simon DK.

Journal: Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 13;14(1):7295.

PMID: 37957154 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the team at Mission Therapeutics were working with Prof David Simon of Harvard University:

Prof David Simon. Source: Simonlab

Prof David Simon. Source: Simonlab

The researchers started by genetically engineering mice so that the mice produced no USP30. These USP30 ‘knock-out’ mice were found to be viable, they grew up into adulthood, and they showed no overt pathology. Interestingly, cells from these mice were found to have enhanced levels of mitophagy in dopaminergic neurons.

Next, the researchers modelled Parkinson’s in the USP30 ‘knock-out’ mice, using a virus that increased levels of the a defective form of alpha synuclein that accumulates in dopamine neurons (this is the AAV-A53T-SNCA mouse model). The scientist found that the absence of USP30 resulted in reduced dopamine neurodegeneration (compared to normal mice that produce USP30 that had be injected with the AAV-A53T-SNCA virus). The absence of USP30 appeared to inhibit the development of alpha synuclein pathology. And the reduction in neurodegeneration was also associated with better outcomes in terms of motor deficits in the mice.

After establishing that the USP30 knockout conditions are safe and reduce neurodegeneration in mice, the scientists then shifted their attention to a drug that Mission Therapeutic has been developing called ‘MTX115325’.

What does MTX115325 do?

MTX115325 is a USP30 inhibitor.

The researchers have established that this drug can cross the blood brain barrier (the protective layer surrounding the brain), and it can also be given orally (rather than needing to be injected). MTX115325 was also safe and well tolerated in mice.

When the scientists injected normal mice with the AAV-A53T-SNCA virus, they observed neurodegeneration in the dopamine neurons. But when they treated the mice with MTX115325, they found that this treatment (at both high dose and low dose) prevented the dopaminergic neuronal loss. These results were consistent with the USP30 knock-out mice studies, indicating that pharmacological inhibition of USP30 could be an interesting approach to clinically test in people with Parkinson’s.

Are there any clinical trials of USP30 inhibition in Parkinson’s?

Not yet, but in a press release associated with the study above, Mission Therapeutics stated that they are planning to initiate a MTX115325 Phase I trial in humans in early 2024.

Are Mission Therapeutics the only biotech company looking at USP30?

Nope.

In September 2022, the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk acquired the biotech firm Forma Therapeutics (Source). We have previously discussed on the SOPD the work that Forma Therapeutics have been doing on DUB inhibitors with researchers at Oxford University. It will be interesting to see if Novo Nordisk continues that work (they certainly have the resources to!).

Another Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck A/S also appears to have an interest in USP30 inhibition (Source).

The Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai also has researchers looking at USP30 inhibition (Source).

The Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai also has researchers looking at USP30 inhibition (Source).

Vincere Biosciences is busily developing USP30 inhibitors (Source).

And then there is also the Dundee-based biotech company Ubiquigent which actively exploring this space.

I would not be surprised if USP30 inhibition is one of the next big areas of interest for Parkinson’s therapeutics research.

So what does it all mean?

One of the really exciting things about Parkinson’s research at the moment is that there are so many different approaches being explored in terms of novel potential therapies. The inhibition of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP30 is a good example of this. Recently, researchers from Harvard University and the biotech company Mission Therapeutics have published some interesting data suggesting that USP30 inhibition is safe, but also potentially neuroprotective in the context of Parkinson’s. And this approach is actively explored by a large number of other research groups.

Excitingly USP30 is not the only DUB enzyme that is interesting in terms of Parkinson’s. For example, scientists have also been investigating USP8 inhibition and found that it can reduce accumulation of alpha synuclein and protect models of Parkinson’s (Source). DUB inhibition will be an area that we will be keeping an eye on here at the SoPD HQ and we will be sure to bring you updates as they come to hand.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Mission

3 thoughts on “On a mitophagy MISSION”