|

# # # # Since the results of a Phase 2b clinical trial were published in 2017, the Parkinson’s community has focused a lot of attention on a class of diabetes drugs called Glucagon-like peptide-1 (or GLP-1) agonists. Last year, the results of another Phase 2 GLP-1 agonist study in Parkinson’s provided further encouraging data. And a lot of people had high hopes for a large Phase 3 clinical trial that reported this year. Unfortunately, the new results did not replicate the previous findings. In today’s post, we will look at what GLP-1 agonists are, what the Phase 3 results report, and consider possible next steps for the field. EDITORIAL NOTE: While the UK Government (National Institute for Health and Care Research) was the primary funder of the Phase 3 exenatide study, Cure Parkinson’s did fund brain imaging and wearable sub-studies attached to the trial. The author of this blog is an employee of Cure Parkinson’s. # # # # |

The Gila monster. Source: Californiaherps

Some interesting facts about the Gila (pronounced ‘Hila’) monster:

- They are named after the Gila River Basin of New Mexico and Arizona (where these lizards were first found – a beautiful part of the world!)

- They are protected by State law

- They are venomous, but very sluggish creatures

- They spend 90% of their time underground in burrows (Source).

Source: docseward

Source: docseward

So how do they survive? What do they eat?

Good question. They are opportunistic and infrequent eaters. When outside, Gila monsters will eat small birds, snakes, lizards, frogs, and insects. They store fat in their tails and as a result they do not need to eat often. Wikipedia says that “Three to four extensive meals in spring are claimed to give Gila monsters enough energy for a whole season“, noting that they are “capable of consuming up to one-third of their body weight in a single meal” (Source).

But once they have digested the food, don’t they get hungry after a day or so?

Well, the Gila monster has an amazing ability to maintain a constant blood sugar level even after long periods without food. And this particular feature intrigued some scientists who started digging into the biological mechanism behind this superpower.

And what did they find?

One of the scientists was Dr John Eng, an endocrinologist from the Bronx VA Hospital.

Dr John Eng. Source: Buffalo

Dr John Eng. Source: Buffalo

In 1992, Dr Eng identified a protein that he had isolated from the venom of the Gila monster. It was named exendin-4, but it bore a striking similarity – structurally and functionally – to a human protein, called glucagon like peptide-1 (or GLP-1).

What is GLP-1?

To answer that question, you must first understand what insulin is.

Ok. So what is insulin?

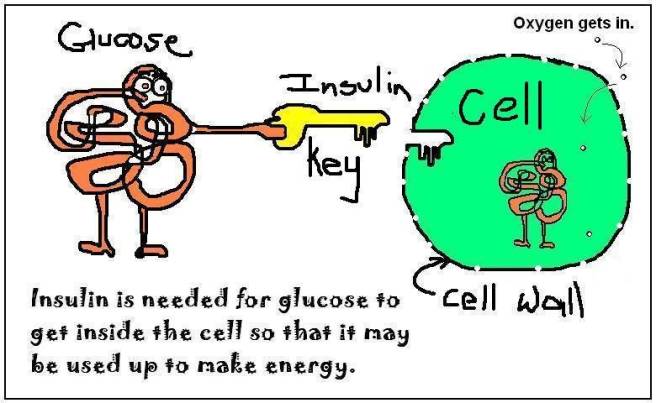

After you eat something, your body will break down that food into constituent parts (such as fats, sugars, protein, etc). The sugar (glucose) will enter the blood stream and raise your blood sugar levels. This process will signal to the pancreas to start producing and releasing insulin.

Insulin is a crucial hormone that regulates glucose levels in your body. It does this by acting like a key to let sugar into your cells, which they then use as a source of energy.

Source: Medium

Source: Medium

So insulin instructs cells to take in and use glucose from the blood?

Exactly.

Ok, and now, what about GLP-1?

Before we do that I need to tell you about another hormone called Glucagon.

Alright: what is Glucagon?

While insulin stimulates cells to take up glucose, this other hormone glucagon has the opposite effect: it tells the body to release glucose into the blood to raise sugar levels.

Ah, I see. So now can you tell me what GLP-1 does?

Yes. GLP-1 is a gut-produced hormone that stimulates insulin production while blocking glucagon release.

The function of GLP-1. Source: Wikipedia

Naturally produced GLP-1 in your body is rapidly deactivated by a circulating enzyme called dipeptidyl peptidase IV (or DPP-4 – click here to read a previous SoPD post on this enzyme). Dr Eng’s newly discovered Exendin-4, however, was found to be resistant to this deactivation, meaning that could last longer in the body stimulating insulin production and blocking glucagon release.

Dr Eng quickly realised that there was enormous medicinal potential for exendin-4, particularly as a drug for people with diabetes (a condition where individuals struggle to control their blood sugar levels).He patented the idea and soon afterwards he licensed it to a San Diego-based biotech company called Amylin Pharmaceuticals which begin the work of turning exendin-4 into a drug for diabetes.

Source: Wikidata

Source: Wikidata

That drug was eventually called Exenatide.

Exenatide. Source: Polypeptide

Exenatide. Source: Polypeptide

Exenatide is a member of a class of drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists.

What is a GLP-1 receptor agonist?

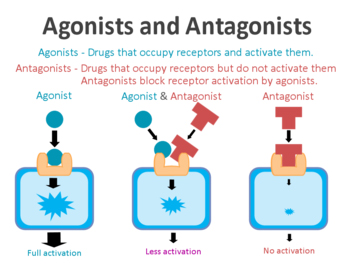

On the surface of cells there are small proteins called receptors, which act like switches for certain biological processes. Receptors will wait for another protein to come along and bind to them. In binding to the receptor, the protein will either activate the receptor or inhibit it. Scientists have developed drugs that function in the same way as these proteins,

The drugs that activate the receptors are called agonists, while the inhibitors are called antagonists.

Agonist vs antagonist. Source: Psychonautwiki

GLP-1 receptor agonists are molecules that activate the GLP-1 receptor.

In April 2005, Byetta (the commercial name for Exenatide) was approved by the FDA for clinical use in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. It was a twice daily formulation of exenatide. On the 27th January 2012, the FDA gave approval for a new formulation of Exenatide called Bydureon, as the first weekly treatment for Type 2 diabetes. In July of 2012, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced it would acquire Amylin Pharmaceuticals for $5.3 billion, and one year later AstraZeneca purchased the Bristol-Myers Squibb share of the diabetes joint venture.

If you want the full history of GLP-1, I can recommend this website, which will give you more background than we have space for here.

|

# RECAP #1: Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas that is released into the blood to help cells absorb glucose, which they use as a source of energy. GLP-1 is a hormone that is produced by the gut and it functions by stimulating insulin production. Drugs that mimic GLP-1 have been developed for the treatment of diabetes. # |

Ok, so why are we discussing GLP-1 agonists here on a Parkinson’s research website?

The binding to the GLP-1 receptor by a GLP-1 receptor agonist results in the activation of many different biological pathways within a cell:

The GLP-1 signalling pathway. Source: Sciencedirect

Some of these pathways are associated with insulin and glucagon-related activity. But some of the other pathways are of particular interest to neurobiology as they deal with “cell death” pathways, reduction of inflammation, limiting oxidative stress, and increasing neurotransmitter release. For a good OPEN ACCESS review on the GLP-1-related research in neurology, click here to read more.

Activation of these pathways got some researchers asking if GLP-1 receptor stimulation could be neuroprotective. And this led to preclinical investigations. This is one of the earliest published reports:

Title: Peptide hormone exendin-4 stimulates subventricular zone neurogenesis in the adult rodent brain and induces recovery in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Bertilsson G, Patrone C, Zachrisson O, Andersson A, Dannaeus K, Heidrich J, Kortesmaa J, Mercer A, Nielsen E, Rönnholm H, Wikström L.

Journal: J Neurosci Res. 2008 Feb 1;86(2):326-38.

PMID: 17803225

In this study, exendin-4 (the protein very similar to exenatide) was tested in a rat model of Parkinson’s. Five weeks after giving the neurotoxin (6-hydroxydopamine) to the rats, the investigators began treating the animals with exendin-4 over a 3 week period. Despite the delay in starting the treatment, the researchers found behavioural improvements and a reduction in the number of dying dopamine neurons.

And this first result was followed a couple of months later by a similar report with a very similar set of results:

Title: Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor stimulation reverses key deficits in distinct rodent models of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Harkavyi A, Abuirmeileh A, Lever R, Kingsbury AE, Biggs CS, Whitton PS.

Journal: J Neuroinflammation. 2008 May 21;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-19.

PMID: 18492290 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The scientists in this study tested exendin-4 on two different rodent models of Parkinson’s (6-hydroxydopamine and lipopolysaccaride), and they found similar results to the previous study. The drug was given 1 week after the animals developed the motor features, but the investigators still reported positive effects on both motor performance and the survival of dopamine neurons.

In 2009, a third group of researchers reported neuroprotection in models of Parkinson’s:

Title: GLP-1 receptor stimulation preserves primary cortical and dopaminergic neurons in cellular and rodent models of stroke and Parkinsonism.

Title: GLP-1 receptor stimulation preserves primary cortical and dopaminergic neurons in cellular and rodent models of stroke and Parkinsonism.

Authors: Li Y, Perry T, Kindy MS, Harvey BK, Tweedie D, Holloway HW, Powers K, Shen H, Egan JM, Sambamurti K, Brossi A, Lahiri DK, Mattson MP, Hoffer BJ, Wang Y, Greig NH.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jan 27;106(4):1285-1290.

PMID: 19164583 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers found that both GLP-1 and exendin-4 provided protection to stressed cells in culture (but not in cells in which the GLP-1 receptor had been deleted). They then assessed exendin-4 in a stroke model and found that this treatment reduced brain damage and improved functional outcomes. Next they shifted their attention to Parkinson’s and found that exendin-4 administration protected dopaminergic neurons in a neurotoxin (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s.

Additional positive data in preclinical models of Parkinson’s ultimately led to the clinical testing of the GLP-1 receptor agonist, exenatide. The first clinical trial of exenatide in Parkinson’s was a Phase 2a trial to determine if the drug was safe to use in people with Parkinson’s.

The results of the trial were published in 2013:

Title: Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Aviles-Olmos I, Dickson J, Kefalopoulou Z, Djamshidian A, Ell P, Soderlund T, Whitton P, Wyse R, Isaacs T, Lees A, Limousin P, Foltynie T.

Journal: J Clin Invest. 2013 Jun;123(6):2730-6.

PMID: 23728174 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers gave exenatide (the Byetta formulation which is injected twice daily) to a group of 21 people with moderate Parkinson’s and evaluated their progress over a 14 month period. They compared this treated group with 24 additional participants with Parkinson’s who acted as control (they received no treatment beyond their standard care). Exenatide was well tolerated by the participants, although there was some weight loss reported among many of the participants (one individual could not complete the study due to weight loss).

Most importantly though, the exenatide-treated individuals demonstrated improvements in their Parkinson’s movement symptoms (as measured by the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (or MDS-UPDRS)), while the comparison patients continued to show decline.

More interesting than this, in a two year follow up study – which was conducted 12 months after the participants in this first study stopped receiving exenatide – the researchers found that participants previously exposed to exenatide demonstrated a significant improvement (based on a blind assessment) in their motor features when compared to the control group involved in the study.

It is important to remember, however, that this initial pilot trial was an ‘open-label study’ – that is to say, the participants knew that they were receiving the exenatide treatment so there is the possibility of a placebo effect explaining the improvements. And this necessitated the testing of the efficacy of exenatide in a Phase 2b double blind clinical trial.

And the results of that trial were published last August 2017:

Title: Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

Title: Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

Authors: Athauda D, Maclagan K, Skene SS, Bajwa-Joseph M, Letchford D, Chowdhury K, Hibbert S, Budnik N, Zampedri L, Dickson J, Li Y, Aviles-Olmos I, Warner TT, Limousin P, Lees AJ, Greig NH, Tebbs S, Foltynie T

Journal: Lancet 2017 Aug 3. pii: S0140-6736(17)31585-4.

PMID: 28781108 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In the study, the investigators recruited 62 people with Parkinson’s (average time since diagnosis was approximately 6 years) and they randomly assigned them to one of two groups, exenatide (the Bydureon formulation which is injected once per week) or placebo (32 and 30 people, respectively). The treatment was given for 48 weeks (in addition to their usual medication) and then the participants were followed for another 12-weeks without exenatide (or placebo) in a ‘washout period’.

It is important to remember that in this trial everyone was blind. Both the investigators and the participants. This is referred to as a double-blind clinical trial and is considered the gold standard for testing the efficacy of a new drug.

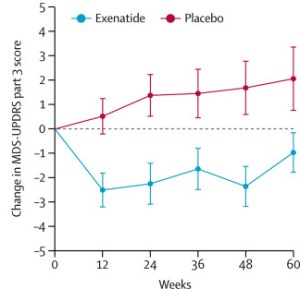

The researchers found a statistically significant difference in the motor scores of the exenatide-treated group verses the placebo group at the end of the study (p=0·0318). As the placebo group continued to have an increasing (worsening) motor score over time, the exenatide-treated group demonstrated improvements, which remained until after the treatment had been stopped for 3 months (weeks 48-60 on the graph below).

Reduction in motor scores in Exenatide group. Source: Lancet

Brain imaging (DaTScan) also suggested a trend towards a reduced rate of decline in the exenatide-treated group when compared with the placebo group. Interestingly, the researchers found no significant differences between the exenatide and placebo groups in scores of cognitive ability or depression – suggesting that the positive effect of exenatide may be more specific to the dopamine or motor regions of the brain.

Given that these results were coming from a randomised, double-blind clinical trial, the Parkinson’s community got rather excited about them (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this particular trial).

Wow, that was a really exciting result!

Indeed. But it wasn’t the only bit of encouraging data that helped to raise expectations. There was also epidemiological research supporting the case for testing GLP-1 receptor agonists in Parkinson’s.

What do you mean?

In 2020, this report was published:

Title: Diabetes medications and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a cohort study of patients with diabetes

Title: Diabetes medications and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a cohort study of patients with diabetes

Authors: Brauer R, Wei L, Ma T, Athauda D, Girges C, Vijiaratnam N, Auld G, Whittlesea C, Wong I, Foltynie T.

Journal: Brain. 2020 Oct 1;143(10):3067-3076.

PMID: 33011770 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers used data from The Health Improvement Network – a large database of anonymised electronic medical records collected from 808 UK primary care clinics. Basically, it is a repository of anonymised medical information about 15 million people.

Within the data, the investigators identified 100, 288 individuals diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes who had been prescribed standard diabetes therapies (glitazones, GLP-1R agonists, and/or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors) on or after the 1st January 2006.

What are glitazones?

Glitazones (also known as thiazolidinediones) is another class of licensed diabetes drug. It reduces insulin resistance by increasing the sensitivity of cells to insulin.

Like GLP-1 receptor agonists, glitazones have been shown to offer protection in animal models of Parkinson’s (Click here and here for more on this). And this class of drug has been clinically tested in Parkinson’s (Click here to read the results of that study).

And what are dipeptidyl…whatever DPP-4 inhibitors?

Again, another type of diabetes treatment (Click here to read an old SoPD post on DPP-4). DPP-4 is a rather indiscriminate enzyme, breaking down a wide range of proteins. A particular protein will do its job and then DPP-4 will come in chew it up and get rid of it. The proteins targeted by DPP-4 include:

- Glucagon

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

- Glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2)

- Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)

Thus, by inhibiting DPP-4, scientists have been able to raise natural levels of proteins that are useful in diabetes, providing a powerful treatment for managing the condition. The diabetes treatment alogliptin is an example of a DPP-4 inhibitor.

Ok, so the researchers identified lots of people who took glitazones, GLP-1R agonists, and/or DPP-4 inhibitors. Then what did they do?

Of the 100, 288 identified cases, there were:

- 21 175 individuals who were prescribed glitazones;

- 36 897 individuals who were prescribed DPP4 inhibitors;

- 10 684 individuals who were prescribed DPP4 inhibitors GLP-1 agonists (6861 of whom were prescribed GTZ and/or DPP4 prior to using GLP-1 mimetics)

Among 100, 288 cases, there were 329 (0.3%) people diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

When the investigators looked at these particular individuals, they found that the use of DPP-4 inhibitors and/or GLP-1R agonists was associated with a lower rate of Parkinson’s (compared to the use of other diabetic treatments).

Specifically, the incidence rate ratio was 0.64 for DPP-4 inhibitors (95% confidence interval 0.43-0.88; P < 0.01) and 0.38 for GLP-1R agonists (95% confidence interval 0.17-0.60; P < 0.01).

What is an incidence rate ratio?

An incidence rate ratio compares how frequently an event (like Parkinson’s) occurs in one group versus another. It is calculated by dividing the incidence rate (new cases per person-time) in an exposed group by the rate in an unexposed (control) group, showing relative risk or benefit, with values >1 indicating higher risk and <1 indicating lower risk.

So an incidence rate ratio of 0.38 for GLP-1R agonists indicates reduced risk of Parkinson’s from taking GLP-1 receptor agonists?

Exactly.

The researchers concluded that the incidence of Parkinson’s in patients diagnosed

with Type 2 diabetes “varies substantially depending on the treatment for diabetes received“. But they added that “We have added to evidence that exenatide may help to prevent or treat Parkinson’s disease, hopefully by affecting the course of the disease and not merely reducing symptoms, but we need to progress with our clinical trial before making any recommendations” (Source).

And this data has further supported the clinical testing of GLP-1 receptor agonists in Parkinson’s.

|

# # RECAP #2: Preclinical data demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor agonists are neuroprotective, across different models of Parkinson’s. Initial clinical studies provided encouraging results for the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide. In addition, epidemiological data suggested an association between GLP-1 receptor antagonist use in diabetics and a reduced risk of Parkinson’s. # # |

So now we get to the Phase 3 exenatide trial results?

You would think, but not just yet.

What do you mean? This is turning into a long post.

I know. But there are a lot of facets to this story and they need to be discussed.

Such as?

Well, exenatide was not the only GLP-1 receptor agonist tested in Parkinson’s. There were a number of additional trials conducted during the same period of time as the Phase 2 exenatide study that should be considered in this narrative. For example, there was a clinical trial of liraglutide.

This study was the conducted at Cedar Sinai in Los Angeles. It involved 63 participants being recruited and randomly assigned (at a ratio of 2:1) to receive either liraglutide (6 mg/ml once daily) or a placebo treatment. The participants were then regularly assessed by the research team for 52 week. The primary endpoint of the study (the pre-determined measure of success for the study) was the changes in the MDS-UPDRS (part III) motor score and the change in non-motor symptoms (as assessed by the NMSS and MDRS-2) after 52 weeks of treatment (Click here to read more about this study).

In the study, 37 people were randomised to liraglutide and 18 were on the placebo treatment. The 52 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment was found to be safe and well tolerated, but unfortunately there was no significant difference between the liraglutide treated group and the placebo group when the investigators looked at motor symptom scores after 1 year of treatment. Both groups appear to have improved slightly. It could be that there was a placebo response at play there (a placebo response being an effect where there is no biological explanation).

The researchers did see a statistically significant response in some non-motor symptoms: The liraglutide treated group experienced improvements in measures of non-motor symptoms, activities of daily living and quality of life, while the placebo group did not.

The full results of the study have never been peer-reviewed and published, but a preprint manuscript of the results is available (Click here to read this). In addition, there is a video of a presentation of the results by the lead investigator Prof Michele Tagliati:

In addition to the liraglutide, there was also a 36-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 study of a new GLP-1 receptor agonist called NLY01 in people with Parkinson’s that was developed by the biotech company Neuraly.

The results of this study have been published:

The results of this study have been published:

Title: Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Title: Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Authors: McGarry A, Rosanbalm S, Leinonen M, Olanow CW, To D, Bell A, Lee D, Chang J, Dubow J, Dhall R, Burdick D, Parashos S, Feuerstein J, Quinn J, Pahwa R, Afshari M, Ramirez-Zamora A, Chou K, Tarakad A, Luca C, Klos K, Bordelon Y, St Hiliare MH, Shprecher D, Lee S, Dawson TM, Roschke V, Kieburtz K.

Journal: Lancet Neurol. 2024 Jan;23(1):37-45.

PMID: 38101901

They recruited 255 people with Parkinson’s in their multi-center study. The recruited participants were randomised into 3 groups – 2.5 mg injection (yes, NLY01 is an injected treatment, just like exenatide), 5.0 mg injection, or placebo. All of the treatments will be self administered once per week for 36 weeks. The primary end point of the study (the measure by which the drug is tested) will be the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS parts II and III – Click here to read more about the details of this trial).

When the trial finished, the investigators found that their results did not meet the primary or secondary endpoints of the study. They found that both doses of NLY01 had no effect on disease progression. Interestingly, they did say that they saw positive indications in some of the exploratory endpoints. And there was some interesting post-hoc analysis presented: When they looked at the age of the participants in the study, the researchers found that the “under 60 years of age” groupings had “nominally significant decreased in the change from baseline in the sum of scores on MDS UPDRS parts II & III at 36 weeks were observed compared with placebo“.

And in addition to these two studies, there was also a Phase 2 trial of lixisenatide conducted in France. The results of that study were published in this report:

Title: Trial of Lixisenatide in Early Parkinson’s Disease.

Title: Trial of Lixisenatide in Early Parkinson’s Disease.

Authors: Meissner WG, Remy P, Giordana C, Maltête D, Derkinderen P, Houéto JL, Anheim M, Benatru I, Boraud T, Brefel-Courbon C, Carrière N, Catala H, Colin O, Corvol JC, Damier P, Dellapina E, Devos D, Drapier S, Fabbri M, Ferrier V, Foubert-Samier A, Frismand-Kryloff S, Georget A, Germain C, Grimaldi S, Hardy C, Hopes L, Krystkowiak P, Laurens B, Lefaucheur R, Mariani LL, Marques A, Marse C, Ory-Magne F, Rigalleau V, Salhi H, Saubion A, Stott SRW, Thalamas C, Thiriez C, Tir M, Wyse RK, Benard A, Rascol O; LIXIPARK Study Group.

Journal: N Engl J Med. 2024 Apr 4;390(13):1176-1185.

PMID: 38598572

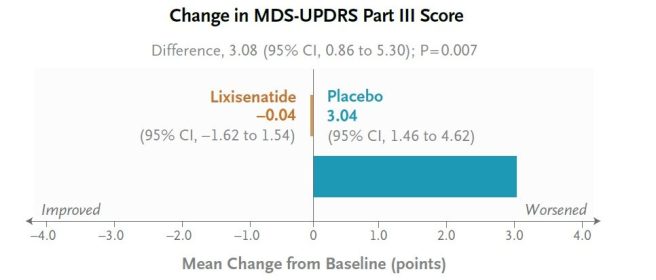

This was a 12-month, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study conducted across 22 research centres in France and involved 156 people with Parkinson’s who were randomised to either lixisenatide (n=78) or to placebo (n=78). The primary end point was the change from baseline in scores on the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part III assessed in the on-medication state at 12 months.

At the start of the study (baseline), the average MDS-UPDRS part III score for both groups was 15. At the end of the treatment period (12 months later), the scores had changed by −0.04 points (indicating improvement) in the lixisenatide group, while it had increased by 3.04 points (indicating worsening) in the placebo group. This was a statistically significant positive result:

This positive outcome did not come without issue though. Participants reported nausea in 46% of cases in the lixisenatide group, and vomiting occurred in 13% of cases. The investigators concluded “lixisenatide therapy resulted in less progression of motor disability than placebo at 12 months in a phase 2 trial but was associated with gastrointestinal side effects. Longer and larger trials are needed”.

For those interested, the results of the Lixisenatide study are presented by one of the trial investigators (Professor Olivier Rascol) in this video from a Cure Parkinson’s Research Update meeting (full disclosure – CP was a co-funder of the trial):

And this collection of more mixed results brings us finally to the Phase 3 exenatide clinical trial results.

|

# # # RECAP #3: There have been multiple clinical trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists in cohorts of Parkinson’s. These studies have included repurposed agents (such as exenatide, lixisenatide, and liraglutide). And the results to date have been mixed, with some studies reporting positive effects in motor progression but nothing else, while another study only found improvements in non-motor outcomes. # # # |

The results of the Phase 3 exenatide trial conducted in the UK have recently been published:

Title: Exenatide once a week versus placebo as a potential disease-modifying treatment for people with Parkinson’s disease in the UK: a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Title: Exenatide once a week versus placebo as a potential disease-modifying treatment for people with Parkinson’s disease in the UK: a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Authors: Vijiaratnam N, Girges C, Auld G, McComish R, King A, Skene SS, Hibbert S, Wong A, Melander S, Gibson R, Matthews H, Dickson J, Carroll C, Patrick A, Inches J, Silverdale M, Blackledge B, Whiston J, Hu M, Welch J, Duncan G, Power K, Gallen S, Kerr J, Chaudhuri KR, Batzu L, Rota S, Jabbari E, Morris H, Limousin P, Greig N, Li Y, Libri V, Gandhi S, Athauda D, Chowdhury K, Foltynie T.

Journal: Lancet. 2025 Feb 22;405(10479):627-636.

PMID: 39919773 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The Phase 3 double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial of exenatide (again, the Bydureon formulation) was set up and conducted across 6 sites in the UK. Participants were randomly assigned (on a 1:1 ratio) to either exenatide (2 mg by subcutaneous pen injection once per week) or a placebo treatment for 96 weeks. The primary outcome of the study was the MDS-UPDRS part III score in the off dopaminergic medication state at the 96 week time point (Click here to read more about the details of this study).

Unfortunately, while the treatment was found to be generally safe and well tolerated, when the clinical data was finally analysed, the investigators observed no difference between the MDS-UPDRS part III scores of the two groups, as you can see in the graph below:

Source: Lancet

Source: Lancet

In addition, they reported that there were no significant differences between the groups in any of the sub-items of the secondary outcomes.

Ohhh.

Indeed.

A disappointing outcome.

So what went wrong?

I don’t think it is a case of anything going “wrong”. The trial team who conducted the study are some of the best of the best. And they did everything by the book. This was a textbook example of a solidly run clinical trial. The fact that the community didn’t get the result it was hoping for is not based on anything “going wrong”.

It could be questioned whether the placebo group progressed rather slowly in the study – perhaps there was a placebo response, one might ask? (similar to the liraglutide study discussed above). In general, the rate of progression differs significantly between individuals and can depend on which stage of the disease people are in, but the average person with Parkinson’s typically progresses at around 2.5 points per year on the MDS-UPDRS part III measure (Click here and here to read more about this). In this Phase 3 study, the exenatide group began with a UPDRS part III score of 32·2 and the placebo group were at 32.3. At the end of the 96 week study, the exenatide group had progressed to 37.6 (an increase of 5.7 points), while the placebo group had progressed to 36·6 (an increase of 4.6 points). So it is unlikely that there is a placebo effect at play.

What about the exenatide group. In the first study, they improved and then remained stable for the rest of the study. But the treatment group in this Phase 3 study didn’t. How can this be explained?

It can’t. The exact same formulation of exenatide was used in both studies. The only difference was the type of delivery pen (used to inject the drug) was changed between the studies by the manufacturer, but this is unlikely to have an impact on an agent that stays in the body for a week.

There are naturally a lot of questions regarding the results and the trial team are now considering every possibility. There is still a lot of ongoing analysis looking at biosamples collected from the participants during the study, and there will be more information to come.

The principle investigator of the trial Professor Tom Foltynie discussed some of these considerations and efforts in a presentation of the Phase 3 exenatide results at another Cure Parkinson’s Research Update meeting (full disclosure – CP funded several substudies of the trial):

Ok, so what happens next?

So, from here I can only offer my own opinion. There will be lots of discussion going forward about the trial, the results and what should happen next.

One thing I am hoping is that we don’t get a chorus of “I told you so”. Drug development is extremely hard (Click here to read about a good case study that might be familiar). I think the field needs to pause, review all of the data and collectively consider next steps. There is a mixed bag of data to digest – some of it suggesting that this class of drugs is doing something in Parkinson’s. But equally, there are many questions that need to be addressed before any next steps. Questions like:

- How much of the GLP-1 receptor agonist needs to get into the brain? Do these agents actually need to get into the brain? Or are any beneficial effects occurring elsewhere in the body?

- Which people should be selected for a clinical trial? The epidemiological data is all based on people with diabetes, so perhaps that could be a starting point. But would this be disease modification for Parkinson’s, or simply better treatment of diabetes?

- What measures of target engagement can be used to determine if these drugs are actually doing what we hope they are doing? This is a perennial issue for clinical trials in Parkinson’s (and neurology in general, given that the brain can’t be biopsied)

- Is modulating GLP-1 biology by itself enough? Or should we be considering GLP-1 receptor agonists in combination with something else? This introduces new levels of complexity, but may be necessary in order to see a shifting of the needle to slow Parkinson’s.

We need answers to these fundamental questions before rushing into another trial.

Do you think this is the end for GLP-1 receptor agonists in Parkinson’s?

No. There is certainly enough interest in GLP-1 biology in neurodegeneration that we will continue to see further research.

For example, we are still waiting for the results of the Phase 2 Stockholm exenatide study to be published. This was an 18-month study in 60 people with Parkinson’s who were treated with exenatide or placebo (Click here to read more about this). In addition, there is the ‘MOST-ABLE” study in Osaka, Japan. This is a 12-month, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 study investigating oral semaglutide tablets (7 mg or 14 mg or placebo) in 99 participants with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this study).

There will also be data coming from other fields of neurodegeneration. For example in December (2025), the pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk will be presenting the results of the EVOKE 3 and EVOKE Plus trials of semaglutide in early-stage Alzheimer’s.

These two trials are randomised, double-blinded, enrolled a total of 3808 participants and evaluating the efficacy and safety of the agent (Click here and here to read more about these study). Although these two studies are not in Parkinson’s, given the size/scale of them, their outcomes could be implications for our field.

In addition, there are a number of biotech companies that have been developing novel GLP-1 receptor agonists for neurodegenerative indications, and some of them have taken a slightly different approach. For example, one biotech called Kariya Pharmaceticals has been developing a drug called KP405, which combines a GLP-1 receptor agonist with a glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (or GIP) agonist.

Dual-agonist combinations are already being developed for diabetes (see Tirzepatide from Eli Lilly or Survodutide from Zealand Pharma), but KP405 has been designed to penetrate the blood brain barrier for testing in neurodegenerative conditions. Like GLP-1, GIP also stimulates insulin secretion (Click here to read more about this). And like GLP-1, agonists of GIP have been reported to be neuroprotective in models of Parkinson’s (Click here and here to read more about this).

So no, I do not think this is the end for GLP-1 research in Parkinson’s.

So what does it all mean?

Mark Twain once wrote: “A man has no business to be depressed by a disappointment, anyway; he ought to make up his mind to get even”.

Twain didn’t have Parkinson’s of course, but there is some truth to his words.

After a lot of encouraging data from preclinical models of neurodegeneration, in addition to supportive epidemiological data and early positive clinical trial results, the Phase 3 exenatide results were not what we hoped for, but this is not the end.

The research community needs to re-group and review the situation before determining next steps. It will be interesting to see in which directions activities progress. There are already elements of work that one can see need to be addressed, but which to prioritise will be important.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

ADDENDUM – 24th November 2025:

Today the results of the Novo Nordisk EVOKE 3 and EVOKE+ studies were announced today. The company reported that the semaglutide invention (in 3808 early-stage Alzheimer’s patient) did not “translate into a delay of disease progression” even as it “resulted in improvement of AD-related biomarkers” (Click here to read more about this).

EDITOR’S NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The author of this post is an employee of Cure Parkinson’s, so he might be a little bit biased in his views on trials supported by the trust. That said, the trust has not requested the production of this post, and the author is sharing it simply because it may be of interest to the Parkinson’s community.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from m3ins