Last week a research report was published in the prestigious journal Science Translational Medicine (that means that it’s potentially really important stuff). The study involved a new drug that is being clinically tested for diabetes.

In last week’s study, however, the new drug demonstrated very positive effects in Parkinson’s disease.

In today’s post we will review the new study and discuss what it means for Parkinson’s.

Diabetic checking blood sugar levels. Source: Gigaom

FACT: One in every 19 people on this planet have diabetes (Source: DiabetesUK).

It is expected to affect one person in every 10 by 2040.

Diabetes (or ‘Diabetes mellitus’) is basically a group of metabolic diseases that share a common feature: high blood sugar (glucose) levels for a prolonged period. There are three types of diabetes:

- Type 1, which involves the pancreas being unable to generate enough insulin. This is usually an early onset condition (during childhood) and is controlled with daily injections of insulin.

- Type 2, which begins with cells failing to respond to insulin. This is a late/adult onset version of diabetes that is caused by excess weight and lack of exercise.

- Type 3, occurs during 2-10% of all pregnancies, and is transient except in 5-10% of cases.

In all three cases inulin plays an important role.

What is insulin?

Insulin is a chemical (actually a hormone) that our body makes, which allows us to use sugar (‘glucose’) from the food that you eat.

Glucose is a great source of energy. After eating food, our body releases insulin which then attaches to cells and signals to those cells to absorb the sugar from our bloodstream. Without insulin, our cells have a hard time absorbing glucose. Think of insulin as a “key” which unlocks cells to allow sugar to enter the cell.

What does diabetes have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

So here’s the thing: 10–30% of people with Parkinson’s disease are glucose intolerant (some figures suggest the percentage may be as high as 50%).

Why?

We do not know.

Obviously, however, this ratio is well in excess of the 6% prevalence rate in the general public (Source:DiabetesUK). We have discussed the curious relationship between diabetes and Parkinson’s disease in a previous post (click here to read it).

And the relationship between Parkinson’s disease and diabetes is not a one way street: A recent analysis of 7 large population studies found that people with diabetes are almost 40% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease that non-diabetic people (Click here for more on this).

EDITORIAL NOTE HERE: We would like to point out that just because a person may have diabetes, it does not necessarily mean that they will go on to develop Parkinson’s disease. There is simply a raised risk of developing the latter condition. It is good to be aware of these things, but please do not panic.

We have no idea why there is an association between diabetes and Parkinson’s disease, but each month new pieces of research are published that support the connection between Parkinson’s and diabetes, and this all provides encouraging support for an ongoing clinical trial (which we will discuss below).

So what research has been done?

Well, just this year alone there have been some interesting studies reported. The first piece of research deals with a drug that is used for treating type-2 diabetes:

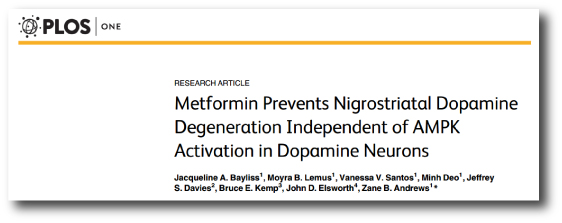

Title: Metformin Prevents Nigrostriatal Dopamine Degeneration Independent of AMPK Activation in Dopamine Neurons.

Author: Bayliss JA, Lemus MB, Santos VV, Deo M, Davies JS, Kemp BE, Elsworth JD, Andrews ZB.

Journal: PLoS One. 2016 Jul 28;11(7):e0159381.

PMID: 27467571 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

Metformin (also known as Glucophage) has been one of the most frequently prescribed drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes since 1958 in the UK and 1995 in the USA. The mechanism by which Metformin works is not entirely clear, but it does appear to increase the body’s ability to recognise insulin.

Metformin treatment has previously been found to be neuroprotective. The researchers in this study wanted to determine if a protein called ‘AMPK’ was involved in that neuroprotective effect. They generated cells that do not contain AMPK and grew dopamine neurons – the brain cells badly affected by Parkinson’s disease.

In both cell cultures and in mice, the researchers found that Metformin was neuroprotective both in normal conditions and in the absence of AMPK. The study could not explain how the neuroprotective potential of Metformin was working, but it adds to the accumulating pile of evidence that some diabetes treatments may be having very positive effects in Parkinson’s disease.

A second piece of research from early this year goes even further:

Title: Reduced incidence of Parkinson’s disease after dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors-A nationwide case-control study.

Authors: Svenningsson P, Wirdefeldt K, Yin L, Fang F, Markaki I, Efendic S, Ludvigsson JF.

Journal: Movement Disorders 2016 Jul 19.

PMID: 27431803

Using the Swedish Patient Register, the researchers of this study identified 980 people with Parkinson’s disease who were also diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between July 1, 2008, and December 31, 2010. For comparative sake, they selected 5 controls (non-Parkinsonian) with type 2 diabetes (n = 4,900) for each of their Parkinsonian+diabetic subjects. Their analysis found a significant decrease in the incidence of Parkinson’s disease among individuals with a history of DPP-4 inhibitor intake.

DPP-4 inhibitors work by blocking the action of DPP-4, which is an enzyme that destroys the hormone incretin. Incretin helps the body produce more insulin only when it is needed and reduce the amount of glucose being produced by the liver when it is not needed. By blocking DPP-4, we are increasing the production of insulin.

Authors concluded that ‘clinical trials with DPP-4 inhibitors may be worthwhile’ in people with Parkinson’s disease.

So what was published last week?

Metabolic Solutions Development is a Kalamazoo (Michigan)-based company that is developing a new drug (MSDC-0160) to treat type 2 diabetes. Last week, Prof Patrik Brundin and colleagues from the Van Andel Institute in Grand Rapids published a research report that suggested MSDC-0160 may have very beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier regulates autophagy, inflammation, and neurodegeneration in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Ghosh A, Tyson T, George S, Hildebrandt EN, Steiner JA, Madaj Z, Schulz E, Machiela E, McDonald WG, Escobar Galvis ML, Kordower JH, Van Raamsdonk JM, Colca JR, Brundin P.

Journal: Sci Transl Med. 2016 Dec 7;8(368):368ra174.

PMID: 27928028

The drug from Kalamazoo, MSDC-0160, functions by reducing the activity of a recently identified protein that carries pyruvate into mitochondria.

What does this mean?

Pyruvate is a very important molecule in our body. The body can make glucose from pyruvate through a process called gluconeogenesis, which simply means production of new glucose. Thus, pyruvate is essential in providing cells with fuel to create energy (for more on pyruvate, click here for a good review article).

Pyruvate is carried into the power house of the cell – the mitochondria – by a protein called mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC). The drug from Kalamazoo, MSDC-0160, is a blocker of MOC. It reduces the activity of MPC.

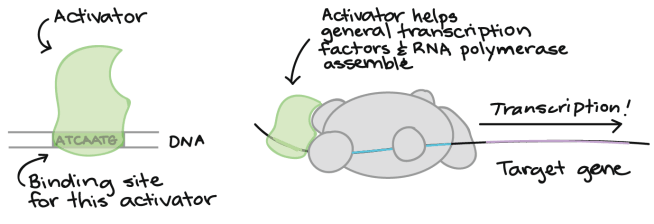

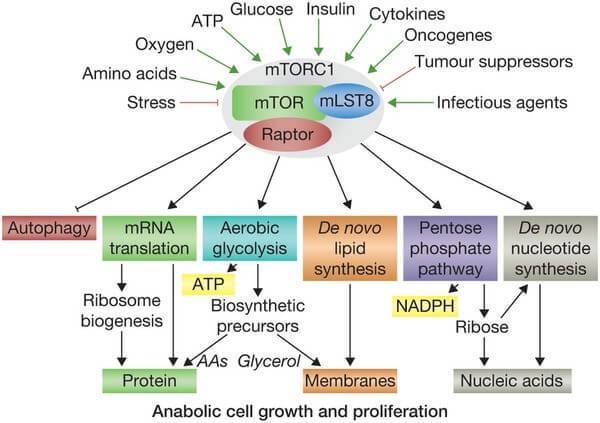

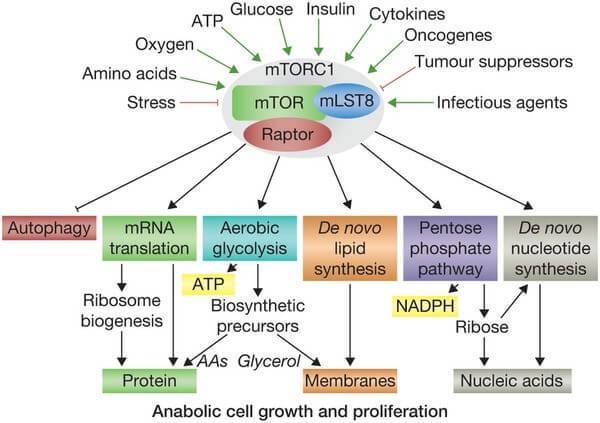

MPC also has other functions. It is known to be a key controller of certain cellular processes that influences mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation. mTOR responds to signals to nutrients, growth factors, and cellular energy status and controls the cells response. For example, insulin can signal to mTOR the status of glucose levels in the body. mTOR also deals with infectious or cellular stress-causing agents, thus it could be involved in a cells response to conditions like Parkinson’s disease.

Things that activate mTOR. Source: Selfhacked

Given the interaction with mTOR, the researchers in Michigan hypothesised that MSDC-0160 might reduce the neurodegeneration of dopaminergic neurons in animal models of Parkinson’s disease.

And this is exactly what they found.

The researchers reported that MSDC-0160 protected dopamine neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. It also protected human midbrain dopamine neurons grown in cell culture when they were exposed to a toxic chemical. In addition, it demonstrated neuroprotective effects in a worm (called Caenorhabditis elegans) that produces a lot of the parkinson’s related protein alpha synuclein. MSDC-0160 even slowed the cell loss observed in a genetically engineered mouse that exhibits a slow loss of dopamine neurons. Basically, treatment with MSDC-0160 protected the cells from whatever the researcher threw at them.

How did it do this?

The researchers found that MSDC-0160 was reducing mTOR activity and also initiating a process called autophagy (which is the garbage disposal system of the cell). By kick starting the rubbish removal system, the cells were healthier. In addition, treatment with MSDC-0160 resulted in less inflammation – or activation of the immune system – in the brain.

Sounds very interesting. When do clinical trials start?

We’re not sure. They will most likely be in the planning stages though. If MSDC-0160 is approved for diabetes, it will be easier to have it approved for Parkinson’s disease as well.

Other diabetes drugs, however, are currently being tested in clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease. Of particular interest is Exenatide, which is just finishing a placebo-controlled, double blind phase 2 clinical trial. We are expecting the results for that trial early next year. Previous clinical studies suggested very positive results for Exenatide:

Title: Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Aviles-Olmos I, Dickson J, Kefalopoulou Z, Djamshidian A, Ell P, Soderlund T, Whitton P, Wyse R, Isaacs T, Lees A, Limousin P, Foltynie T.

Journal: J Clin Invest. 2013 Jun;123(6):2730-6.

PMID: 23728174 (This study is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers running this clinical study gave Exenatide to a group of 21 patients with moderate Parkinson’s disease and evaluated their progress over a 14 month period (comparing them to 24 control subjects with Parkinson’s disease). Exenatide was well tolerated by the participants, although there was some weight loss reported amongst many of the subjects (one subject could not complete the study due to weight loss). Importantly, Exenatide-treated patients demonstrated improvements in their clinician assessed PD ratings, while the control patients continued to decline. Interestingly, in a two year follow up study – which was conducted 12 months after the patients stopped receiving Exenatide – the researchers found that patients previously exposed to Exenatide demonstrated a significant improvement (based on a blind assessment) in their motor features when compared to the control subjects involved in the study.

Exenatide. Source: Diatribe

The results of that initial clinical study were intriguing and exciting, but it is important to remember that the study was open-label: the subjects knew that they were receiving the drug. This means that we can not discount the placebo effect causing some of the beneficial effects reported.

And Exenatide is not the only diabetes drug being tested

Pioglitazone is another licensed diabetes drug that is now being tested in Parkinson’s disease. It reduces insulin resistance by increasing the sensitivity of cells to insulin. Pioglitazone has been shown to offer protection in animal models of Parkinson’s disease (click here and here for more on this). And the drug is currently being tested in a clinical trial.

So what does it all mean?

People with diabetes appear to be more vulnerable than the general population to developing Parkinson’s disease, and many people with Parkinson’s disease have glucose processing issues. It would be very interesting to better understand the link between Parkinson’s disease and diabetes. Why is it that so many people with Parkinson’s disease are glucose intolerant? And why do so many people with diabetes go on to develop Parkinson’s? Answering either of these questions might provide further insight into how both conditions function. And given that drugs associated with one appear to help with the other only strengthens the curious association.

As mentioned above, 2017 will bring the results of Exenatide clinical trial, upon which a lot of hope is riding. If it provides positive benefits, then we will finally have a treatment that can slow the progression of the disease. In addition, we will be able to delve more deeply into how Exenatide is causing it’s effect. Positive outcomes for Exenatide will also open the flood gates for many of the other clinically approved diabetes medications which could be trialled on people with Parkinson’s disease.

So despite how you may be feeling about 2017 (based on the events of 2016), we here at the SoPD believe that there is a lot to look forward to in the new year.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Diabetes60systems