|

# # # # Mitochondria are curious little structures that live symbiotically within cells. They are believed to derive from an ancient bacterial past, and they still retain elements of that forgotten occupation: They have their own DNA. Given that mitochondria are very metabolically active, that mitochondrial DNA can be vulnerable to damage. Recently, researchers have proposed that damage to mitochondrial DNA might be a useful biomarker for Parkinson’s. In today’s post, we will look at what mitochondria do, what damage to their DNA means, and how this could be very useful for our understanding of Parkinson’s. # # # # |

Source: Szegedify

Source: Szegedify

In Chinese culture, 2023 has been in the Year of the Rabbit.

The Rabbit is a symbol of longevity, peace and prosperity. As such, 2023 is predicted to be a year of hope.

Here at SoPD HQ, we think 2023 has been the Year of the Biomarker.

Think about it. Over the course of this year, we have covered a couple of new reports proposing the alpha synuclein seeding assay (Click here to read more about this) and DOPA decarboxylase levels in cerebrospinal fluid as potentially useful markers for Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this).

And recently, researchers have proposed another biomarker which involves an important aspect of Parkinson’s associated biology: Mitochondria.

Remind me: What are mitochondria?

Mitochondria are tiny bean shaped objects that reside inside of almost every cell in your body.

Mitochondria. Source: Ohiostate

Mitochondria. Source: Ohiostate

Each mitochondrion (singular) functions as a power station providing the cell with energy to do its tasks. There are hundreds – often thousands – of them per cell (heart cells contain between 5,000 and 8,000 mitochondria each – source), being moved around internally as needs dictate.

We talk about mitochondria a lot on this website, but they are truly fascinating structures.

I am not a “mitochondriac” (a scientist with a chronic and unusually intense interest in all things mitochondria), but they do hold the balance between life and death for cells. And that hold on cell fate extends a long way back in evolution. Mitochondria are believed to be ancient bacteria that were consumed by an equally ancient cell over 1.45 billion years ago and since then they have maintained a symbiotic relationship: The cells provide the food for mitochondria and the mitochondria turn that food into energy for the cells (Click here to read more about the evolution of mitochondria).

But some of the relics of that ancient bacterial past still appear to exist.

What do you mean?

Well it is curious that mitochondria have their own DNA.

What? Why would they have their own DNA?

Most of the DNA in cells is kept in the nucleus. Stored safely in the tightly bound chromosomes of the nucleus is approximately 3 billion base pairs of nucleic DNA. But outside of the nucleus, there are small amounts of mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondrial DNA contains 16,569 base pairs, and it is kept in a circular formation (the same as bacteria) inside of mitochondria:

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Now the curious thing about mitochondrial DNA is that it only encodes (contains the instructions) for 14 proteins. The rest of the proteins that the mitochondria needs to function, come from DNA that is kept in the nucleus of the cell.

But I thought that the mitochondria are the power stations. Isn’t a power station kind of a dangerous place to keep DNA?

Yes, indeed.

In generating energy for cells, mitochondria produce a lot of nasty by-products that can damage mitochondrial DNA. This damage can result in broader dysfunction in the mitochondria, as well as cause stress on the cell. But there are also lots of mechanisms that counter balance this, and help to repair damage done to mitochondria.

Interesting. So how have mitochondria become a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s?

Well, it comes back to that DNA damage that we were just talking about.

How so?

This is Prof Laurie Sanders of Duke University (go Devils!):

Before moving to North Carolina to start her own lab, she was working with a legend in the Parkinson’s field – Prof Tim Greenamyre at Pittsburgh University:

And back in 2014, together with collaborators, they published this report:

Title: LRRK2 mutations cause mitochondrial DNA damage in iPSC-derived neural cells from Parkinson’s disease patients: reversal by gene correction.

Title: LRRK2 mutations cause mitochondrial DNA damage in iPSC-derived neural cells from Parkinson’s disease patients: reversal by gene correction.

Authors: Sanders LH, Laganière J, Cooper O, Mak SK, Vu BJ, Huang YA, Paschon DE, Vangipuram M, Sundararajan R, Urnov FD, Langston JW, Gregory PD, Zhang HS, Greenamyre JT, Isacson O, Schüle B.

Journal: Neurobiol Dis. 2014 Feb;62:381-6.

PMID: 24148854 (this report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

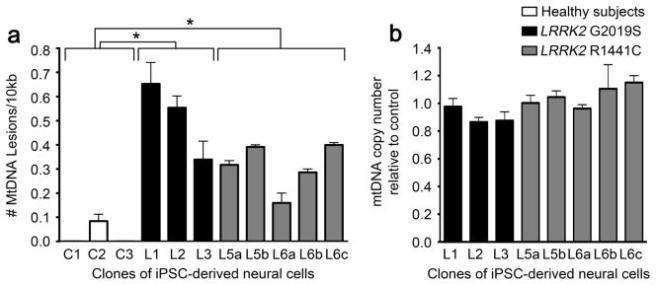

In this study, they looked at the levels of mitochondrial DNA (MtDNA) damage in neural cells derived from five people with Parkinson’s-associated LRRK2 genetic variants, and they compared this to cells from three unaffected control individuals (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on LRRK2 and it’s role in PD). When they analysed their data, the researchers found a significantly elevated level of MtDNA damage in the LRRK2 cells. See panel A (left graph) in the image below – the control cells (C1, C2 & C3) have very little MtDNA damage compared to the LRRK2-PD cells (L1, L2, etc):

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

There was no difference in the amount of MtDNA being analysed (see the panel B graph above) and the samples were all assessed under the same circumstances. They also double checked themselves by looking at MtDNA damage levels in cells from siblings of some of the PD volunteers to make sure the result did not arise a familial issue. But the siblings levels of MtDNA damage did not differ from control cells, so there was something specific to the LRRK2-PD individuals.

They next genetically edited the LRRK2 genetic variations – replacing the dysfunctional section of LRRK2 DNA with a normal LRRK2 gene – and they found that this change completely corrected levels of the MtDNA damage:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

Intrigued, they began to wonder if MtDNA damage could be an potential biomarker for LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s neuronal dysfunction.

To further assess the potential of this finding, they next wanted to look at what was happening inside the Parkinsonian brain.

|

# RECAP #1: Mitochondria are tiny batteries inside of cells that provide the energy required for normal cellular function. Mitochondria carry some of their own DNA, which can often get damaged. Researchers have proposed that damage to mitochondrial DNA might be a biomarker for Parkinson’s. # |

What did they find in the Parkinsonian brain?

Interesting results. And in 2014, they published the results of that investigation in this report:

Title: Mitochondrial DNA damage: molecular marker of vulnerable nigral neurons in Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Mitochondrial DNA damage: molecular marker of vulnerable nigral neurons in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Sanders LH, McCoy J, Hu X, Mastroberardino PG, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ, Chu CT, Van Houten B, Greenamyre JT.

Journal: Neurobiol Dis. 2014 Oct;70:214-23.

PMID: 24981012 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers collected postmortem samples of midbrain and cerebral cortex from six people who passed away with Parkinson’s and five individuals who passed away without Parkinson’s acted as controls. They looked at the dopamine neurons (which are the most vulnerable neurons affected by Parkinson’s) in these samples to see if there was any difference in MtDNA damage levels between the brains.

And guess what they found?

That’s right: high levels of MtDNA damage markers in the dopamine neurons of the Parkinson’s samples, but not the control samples:

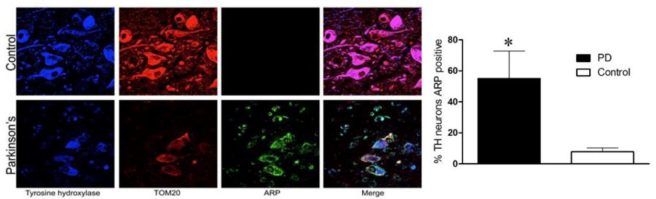

Tyrosine Hydroylase (TH) labels dopamine neurons (in Blue), TOM20 labels mitochondria (in Red), Aldehyde reactive probe (ARP) labels damaged MtDNA (in Green). Source: PMC

Tyrosine Hydroylase (TH) labels dopamine neurons (in Blue), TOM20 labels mitochondria (in Red), Aldehyde reactive probe (ARP) labels damaged MtDNA (in Green). Source: PMC

The researchers reported that in the Parkinson’s cases, 55% of the remaining dopamine neurons exhibited evidence of MtDNA damage, while only 8% of dopamine neurons in control samples had signs of MtDNA damage. Curiously, they did not find the same results in neurons analysed in the cerebral cortex (another region of the brain that is not as badly affected as the dopamine neurons). And it is important to note here that these Parkinson’s samples were not coming from just LRRK2-PD cases, but rather individuals with just spontaneous Parkinson’s. Therefore, the researchers began to speculate that MtDNA damage might be a biomarker for the broader Parkinson’s-affected community.

The scientists next looked in animal models of Parkinson’s. For this analysis, they used the rotenone model. Rotenone is a pesticide that targets mitochondria and stops them from functioning properly. The researchers found MtDNA damage in the dopamine neurons prior to their neurodegeneration, which further stimulated their thinking that MtDNA damage could be a potential biomarker.

In a follow up report, Dr Sanders and colleagues explored the mechanism of this MtDNA damage phenomenon in the context of Parkinson’s. This is the report:

Title: LRRK2 G2019S-induced mitochondrial DNA damage is LRRK2 kinase dependent and inhibition restores mtDNA integrity in Parkinson’s disease.

Title: LRRK2 G2019S-induced mitochondrial DNA damage is LRRK2 kinase dependent and inhibition restores mtDNA integrity in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Howlett EH, Jensen N, Belmonte F, Zafar F, Hu X, Kluss J, Schüle B, Kaufman BA, Greenamyre JT, Sanders LH.

Journal: Hum Mol Genet. 2017 Nov 15;26(22):4340-4351.

PMID: 28973664 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the research team examined the role of the LRRK2 kinase region in causing MtDNA damage.

Hang on a second. What exactly is LRRK2 and what on Earth is it’s kinase region?

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (or LRRK2 – pronounced ‘lark 2’ – also known as ‘Dardarin‘ (from the Basque word “dardara” which means “trembling”) – is an protein that has many functions within a cell – from supporting efforts to move things around inside the cell to helping to keep the power on (via mitochondrial function). It is a busy and important protein.

The many jobs of LRRK2. Source: Researchgate

The many jobs of LRRK2. Source: Researchgate

The LRRK2 gene – the section of DNA that provides the instructions for making LRRK2 protein – is made up of many different regions. Each of those regions is involved with the different functions of the eventual protein. As you can see in the image below, the regions of the LRRK2 gene have a variety of different functions:

The regions and associated functions of the LRRK2 gene. Source: Intechopen

The regions and associated functions of the LRRK2 gene. Source: Intechopen

Tiny genetic errors or variations within the LRRK2 gene are recognised as being some of the most common genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s, with regards to increasing ones chances of developing the condition (LRRK2 variants are present in approximately 1-2% of all cases of Parkinson’s).

The structure of Lrrk2 and where various mutations lie. Source: Intech

The structure of Lrrk2 and where various mutations lie. Source: Intech

As the image above suggests, mutations in the PARK8 gene are also associated with Crohn’s disease (Click here and here for more on this) – although that mutation is in a different location to those associated with Parkinson’s. One particularly common Parkinson’s-associated LRRK2 mutation – called G2019S – is also associated with increased risk of certain types of cancer, especially for hormone-related cancer and breast cancer in women (Click here to read more about this). If you have a G2019S mutation, there is no reason to panic, it does not mean that you will definitely develop cancer – but it is good to be aware of this association and have regular check ups.

The G2019S variation (the name designates its location on the gene) is the most common LRRK2 mutations. In certain populations of people it can be found in 40% of people with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this).

What is the effect of having the G2019S variation?

If you look at the image above, you will see that this genetic variation sits within the kinase region of the LRRK2 gene.

Ah, the kinase region. What exactly does the kinase region do?

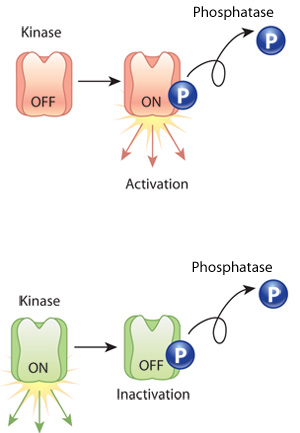

A kinase is an enzyme that regulates the biological activity of other proteins. So LRRK2 can act as an enzyme and regulate the activity of other proteins.

Kinases function by transferring phosphate groups from high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules (like ATP) to specific target proteins – in a process called phosphorylation.

Source: Bmglabtech

Source: Bmglabtech

Wait. What does any of that mean? What is phos…pho…ryl…ation?

Phosphorylation of a protein is basically the process of turning it on or off – making it useful or inactivating it. From allowing a protein to fold in a particular manner to actually activating/deactivating the function of a protein, phosphorylation is a critical function in cellular biology.

Phosphorylation of a kinase protein. Source: Nature

Phosphorylation of a kinase protein. Source: Nature

Phosphorylation occurs via the addition or removal of phosphates. Their addition or removal determines the state of the protein being phosphorylated.

So the kinase region of LRRK2 is important for turning on or turning off other proteins?

In a nut shell, yes.

And am I correct if I assume that the G2019S mutation stops this kinase activity?

No, that would be incorrect.

Rather, quite the opposite.

In the mid 2000s, researchers reported that the G2019S mutation actually increases the kinase activity of LRRK2:

Title: Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity.

Title: Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity.

Authors: West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Nov 15;102(46):16842-7.

PMID: 16269541 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers discovered that the G2019S variation did not have any obvious effect on LRRK2 protein levels or localization within cells. But it did cause an increase in the phosphorylation and the autophosphorylation activity of LRRK2.

Autophosphorylation?

LRRK2 can phosphorylate itself. It can regulate its own activity.

Ok. Got it.

This finding led the investigators to conclude that the G2019S variation may result in a ‘gain-of-function’ mechanism that could be influential in the pathology of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s. In people with the G2019S genetic variation, the kinase region of LRRK2 becomes hyperactive.

And in the carefully balanced environment of a cell, a hyperactive kinase could be like a bull in a china shop if the cell becomes stressed.

So what did Dr Sanders and colleagues learn about the kinase region of LRRK2 in the MtDNA damage effect?

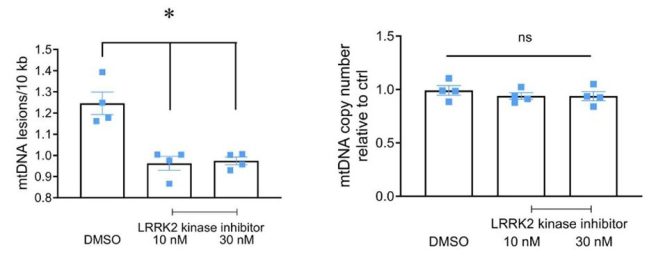

Well, first they demonstrated that normal LRRK2 protein and another version of LRRK2 which has a dead kinase region (this is called the D1994A mutant) had no effect on mtDNA damage. Neither of these types of LRRK2 protein caused an increase in MtDNA damage. But, LRRK2 with the G2019S variant significantly increased MtDNA damage:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

Next, the researchers treated the cells with a drug that inhibits the kinase activity of LRRK2, and they found that this completely reduced the levels of MtDNA damage in the LRRK2-G2019S variant carrying cells. In the image below, when normal cells (labelled with ‘green fluorescent protein’ (GFP) and LRRK2-G2019S cells were treated with DMSO (a neural control substance), MtDNA damage was observed in the LRRK2-G2019S cells. When these same cells were treated with the LRRK2 inhibitor GNE-7915, that MtDNA damage disappeared in the LRRK2-G2019S cells:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

These findings led the researchers to conclude that the LRRK2 G2019S mutation causes MtDNA damage and that it is LRRK2 kinase activity-dependent.

|

# # RECAP #2: Tiny errors in the LRRK2 gene (the region of DNA that provides the instructions for making the LRRK2 protein) increase the risk of developing Parkinson’s. In LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s, the LRRK2 protein becomes hyperactive. Data suggests that this hyperactivity is associated with damage to mitochondrial DNA damage. Pharmacological inhibition of LRRK2 reduces the amount of mitochondrial DNA damage in cells from people with LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s. # # |

Interesting. So what did they do next?

The shifted their attention from cells in culture to cells in people. They collected blood cells from unaffected ‘control’ individuals and people with LRRK2-G2019S associated Parkinson’s and measured MtDNA damage before and after LRRK2 inhibitor treatment.

Here is the report of this study:

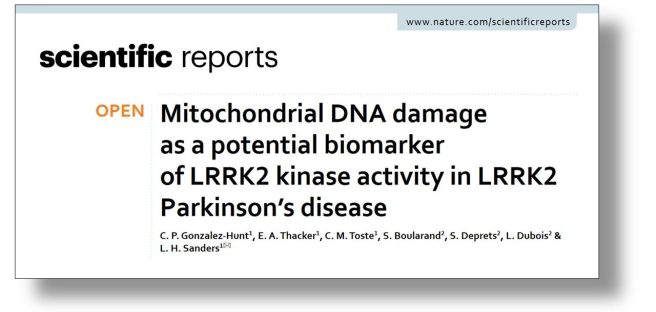

Title: Mitochondrial DNA damage as a potential biomarker of LRRK2 kinase activity in LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Mitochondrial DNA damage as a potential biomarker of LRRK2 kinase activity in LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Gonzalez-Hunt CP, Thacker EA, Toste CM, Boularand S, Deprets S, Dubois L, Sanders LH.

Title: Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 14;10(1):17293.

PMID: 33057100 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, Dr Sanders and team collected peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from three individuals without Parkinson’s (the controls) and three people with LRRK2-G2019S associated Parkinson’s. When they assessed MtDNA damage, they found that it was significantly increased in the immune cells collected from people with LRRK2 G2019S mutations (compared with controls), and again, this effect could be corrected by treatment with LRRK2 inhibitors. These results led the researchers to conclude that “measurement of MtDNA damage is a “surrogate” for LRRK2 kinase activity and consequently of kinase inhibitor activity”.

But that was only in three people with Parkinson’s?

Yes, but very recently the research team has replicated their findings in much larger groups of people with Parkinson’s. They also developed a new method of assessing MtDNA damage and they published their findings in this report:

Title: A blood-based marker of mitochondrial DNA damage in Parkinson’s disease.

Title: A blood-based marker of mitochondrial DNA damage in Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Qi R, Sammler E, Gonzalez-Hunt CP, Barraza I, Pena N, Rouanet JP, Naaldijk Y, Goodson S, Fuzzati M, Blandini F, Erickson KI, Weinstein AM, Lutz MW, Kwok JB, Halliday GM, Dzamko N, Padmanabhan S, Alcalay RN, Waters C, Hogarth P, Simuni T, Smith D, Marras C, Tonelli F, Alessi DR, West AB, Shiva S, Hilfiker S, Sanders LH.

Journal: Sci Transl Med. 2023 Aug 30;15(711):eabo1557.

PMID: 37647388 (this report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

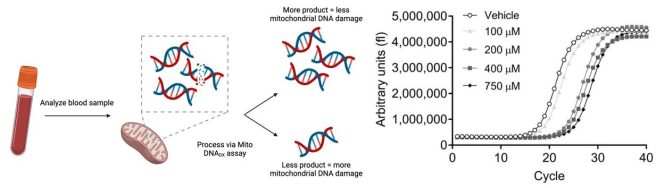

In this study, the researchers developed a new method of assessing MtDNA damage in blood cells that they called Mito DNADX.

Interesting. How does it work?

Mito DNADX is a Polymerase Chain Reaction (or PCR)-based assay.

A what?

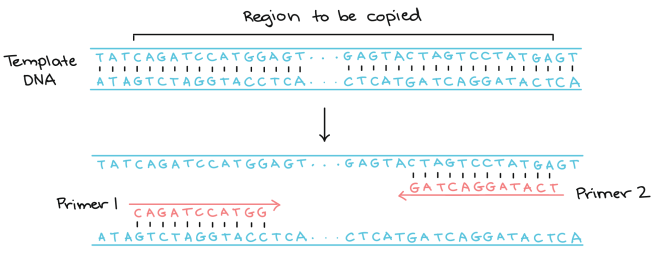

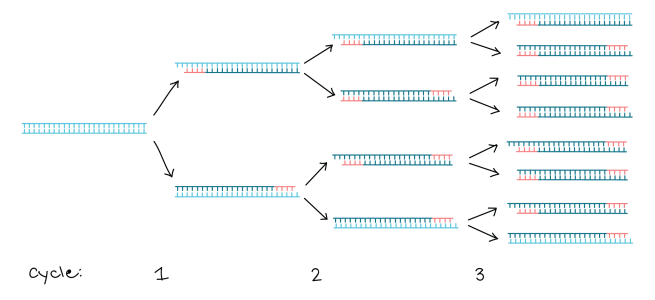

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a widely used laboratory technique for rapidly producing copies of segments of DNA. Million/billions of copies of a particular sequence can be made via a series of amplification cycles.

The foundation of PCR involves the use of short synthetic DNA fragments called “primers“. These are short combination of the AGCT bases that make up DNA, but each primer is designed to be selective for a very specific segment of DNA that is to be amplified. A set of primers is designed for a region of DNA, with primer 1 being specific for one end of the region and primer 2 being specific for the other end:

Source: Khan Academy

Source: Khan Academy

Across multiple rounds of DNA synthesis, the region of interest can be amplified millions of times:

Source: Khan Academy

Source: Khan Academy

For those interested, Khan Academy have a very good page on PCR and this video explains PCR very well:

Ok, so how did Dr Sanders and colleagues use PCR to find MtDNA damage?

Human MtDNA is a short and well characterised sequence. So what Dr Sanders and team did was simply amplify known segments of MtDNA. By doing this, any region of MtDNA that was damaged would result in a blockage of the replication of the segments. And this would result in less DNA product being produced.

So healthy control samples might produce lots of copies of the MtDNA sequence, while the samples with high levels of MtDNA damage would produce far less.

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

And this could be used as a measure of MtDNA damage in blood samples.

I see. So they developed this PCR technique and used it on blood samples from people with Parkinson’s?

For their initial study, they collected blood samples from 21 people with spontaneous Parkinson’s (no genetic risk factors) and two people with Parkinson’s who also carried the LRRK2-G2019S genetic variation. They also collected blood samples from 12 unaffected individuals who acted as controls. They extracted MtDNA from all of the samples and individually analysed them on their Mito DNADX assay.

And they found that the people with spontaneous Parkinson’s had significantly higher levels of MtDNA damage than the controls, and the individuals with LRRK2-G2019S genetic variants had even higher levels of MtDNA damage (and across all of these samples there was no difference in the amount of MtDNA being analysed):

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

They also reported that 24 hours of LRRK2 inhibitor treatment on these blood cells reduced the levels of MtDNA damage in the LRRK2-G2019S cases back down to control levels:

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

Dr Sanders and her team tested their Mito DNADX assay on blood samples from two independent cohorts and they achieved the same result: People with Parkinson’s had higher levels of MtDNA damage than unaffected controls.

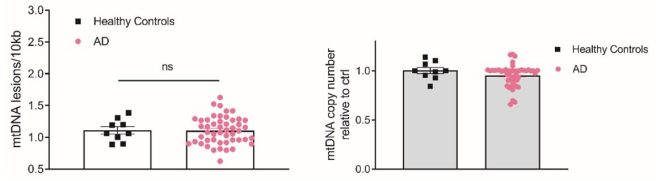

And interestingly, when they tested blood samples from people with Alzheimer’s, the researchers found no evidence of MtDNA damage (compared to controls samples):

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

The researchers finished their report by concluding that “quantifying mtDNA damage using the Mito DNADX assay may have utility as a candidate marker of PD“, as well as being a useful tool for assessing if LRRK2 inhibitors are doing what they should in clinical trials.

|

# # # RECAP #3: Blood collected from people with Parkinson’s has been found to have high levels of MtDNA damage. LRRK2 inhibitors restore levels of MtDNA damage to normal. MtDNA DNA damage could be used not only as a biomarker for Parkinson’s, but also as an assessment of LRRK2 inhibitor efficacy in ongoing clinical trials. # # # |

Interesting. Are there currently clinical trials of LRRK2 inhibitors?

Yes, there are now a few clinical trials assessing LRRK2 inhibitors in Parkinson’s, and a large number of biotech companies with preclinical LRRK2 inhibitor programmes.

Leading the pack is a collaboration between the biotech company Denali Therapeutics and the pharmaceutical company Biogen. They are co-developing a small molecule LRRK2 inhibitor called BIIB122 (previously known as DNL151) in people with Parkinson’s  Earlier this year, the companies published the results of their first clinical trial studies of this agent:

Earlier this year, the companies published the results of their first clinical trial studies of this agent:

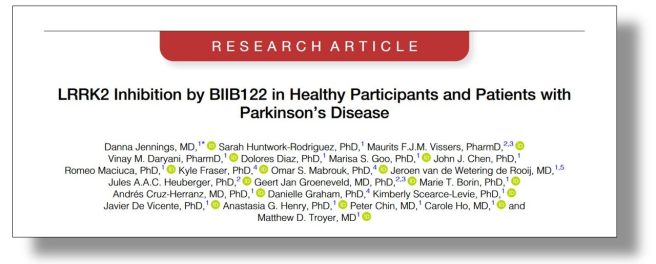

Title: LRRK2 Inhibition by BIIB122 in Healthy Participants and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease.

Title: LRRK2 Inhibition by BIIB122 in Healthy Participants and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease.

Authors: Jennings D, Huntwork-Rodriguez S, Vissers MFJM, Daryani VM, Diaz D, Goo MS, Chen JJ, Maciuca R, Fraser K, Mabrouk OS, van de Wetering de Rooij J, Heuberger JAAC, Groeneveld GJ, Borin MT, Cruz-Herranz A, Graham D, Scearce-Levie K, De Vicente J, Henry AG, Chin P, Ho C, Troyer MD.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2023 Mar;38(3):386-398. doi: 10.1002/mds.29297. Epub 2023 Feb 18.

PMID: 36807624 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this report, the researchers presented the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1 studies, demonstrating the biological effect of their oral LRRK2 inhibitor BIIB122 in 186 healthy volunteers for up to 28 days (NCT04557800 and NCT04056689). The studies looked at single and multiple doses, as well as ascending doses of the inhibitor to determine if it was safe and well tolerated, as well as identifying an effective dose that can be used in a larger Phase 2 clinical trial.

The results of the study demonstrated that the drug was safe and did what it said on the label: It inhibited LRRK2 activity.

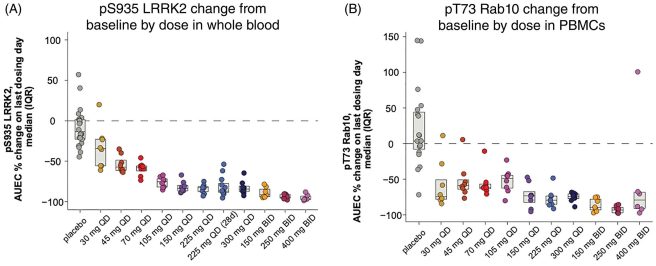

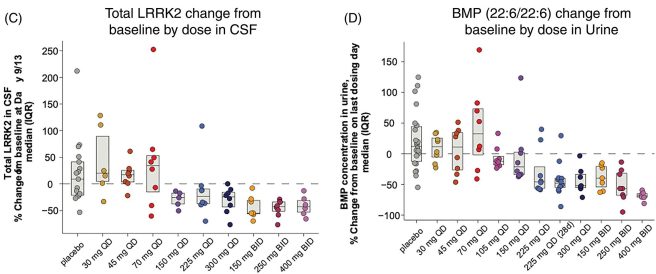

In the graphs below, you can see that as the dose increased, the level of LRRK2 activity in blood cells went down (see panel A). In addition, they found that as the dose of BIIB122 increased, the level of activity in proteins that LRRK2 interacts with (such as RAB10) also went down (see panel B). This was very encouraging data:

Source: MovementDisorders

Source: MovementDisorders

In addition to assessing blood, the researchers also looked at BIIB122 activity in other bodily fluids. Firstly, and most importantly, they analysed samples of cerebrospinal fluid (or CSF). CSF is the liquid that the brain sits in and is often used for evaluating what is happening in the brain itself. Again the researchers found that with increasing doses, their LRRK2 inhibitor reduced the activity of LRRK2 protein (see the graph in panel C below). They also evaluated samples of urine from the participants and found that as the activity of proteins that LRRK2 interacts with (such as BMP) went down as the dose increased (see panel D in the graph below):

Source: MovementDisorders

Source: MovementDisorders

The Denali and Biogen scientists concluded their study by saying that BIIB122 is a safe and tolerable LRRK2 inhibitor that can access the brain and reduce LRRK2 activity to levels. And they were happy for BIIB122 to “advance to late-stage clinical studies in patients with Parkinson’s given its favorable pharmacokinetic profile“.

The Phase 1 studies were completed several years ago now, and Denali and Biogen have already initiated a large Phase 2 study (called the LUMA Study), which is a global study assessing BIIB122 in 644 people with Parkinson’s. The participants are being treated for at least 48 weeks and up to 144 weeks with BIIB122 (Click here for more information about the LUMA study). This study is scheduled to complete at the end of 2025/early 2026.

Interesting. Are there other clinical trials for LRRK2 inhibitors?

Yes.

Biogen appears to be doubling down on LRRK2 as they also have a collaboration with another biotech company called Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and together they are developing a product called BIIB094.

BIIB094 is an antisense oligonucleotide targeting LRRK2.

What is an antisense oligonucleotide?

Antisense oligonucleotides are a method of inhibiting RNA rather than proteins – this means that this drug blocks LRRK2 RNA rather than the subsequent protein (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about antisense oligonucleotides).

Biogen and Ionis have been conducting the REASON study, which has involved 82 individuals with Parkinson’s being evaluated for at least 57 days, but follow up for 169 days (Click here for more information about this study). This study is scheduled to complete in August 2024.

In addition to this approach, there are other biotechs developing small molecule inhibitors (similar that of Denali). In February 2023, the biotech company Neuron23 announced that they had started dosing participants in their Phase 1 clinical trial of a LRRK2 inhibitor called NEU-723 (Click here to read the press release).

And very recently, a Chinese biotech company Guizhou Inochini Technology Co Ltd has initiated Phase 1 clinical testing of their LRRK2 inhibitor WXWH-0226 (Click here for more information about this trial).

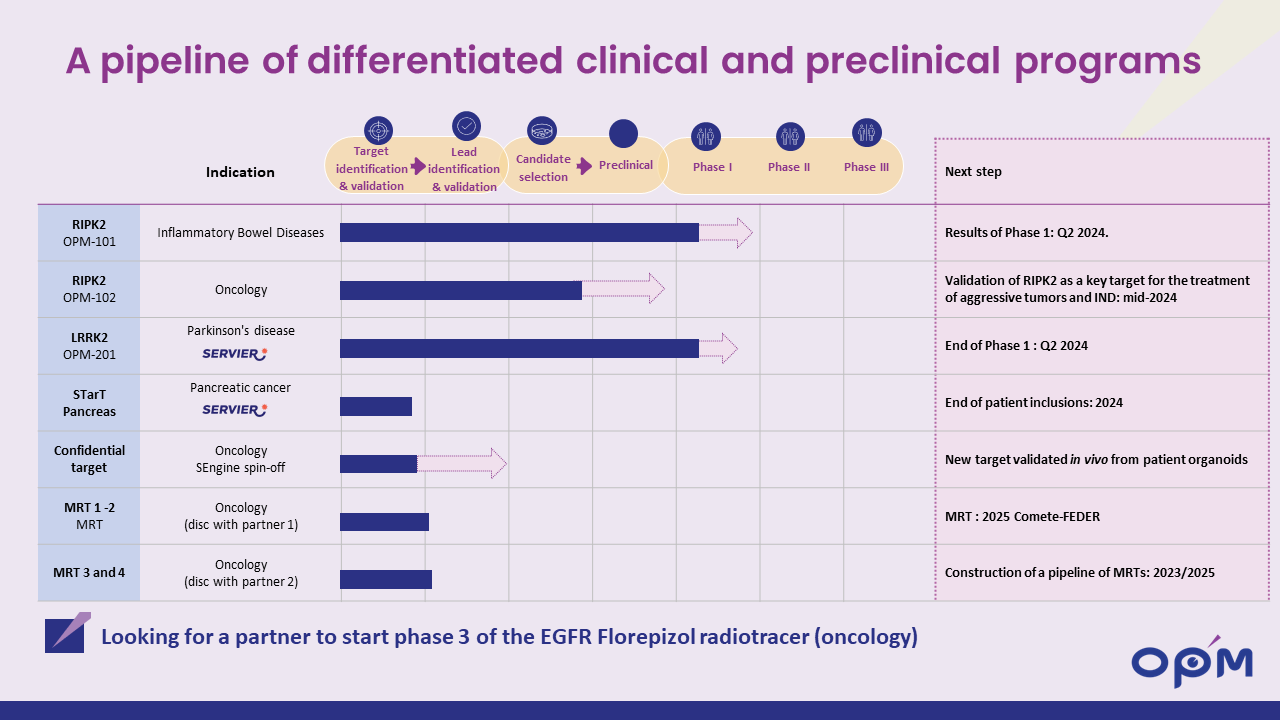

Then there is another LRRK2 inhibitor named OPM-201 is being clinically developed by Oncodesign. The Phase 1a testing in healthy volunteers was scheduled to finish in Q2 2024 (Source), and Phase 1b testing is designated to begin in 2025:

And as I said above, there are a lot of additional companies currently in preclinical development for a variety of approaches to reduce LRRK2 activity in Parkinson’s.

Watch this space.

So what does it all mean?

This is the kind of post that writes itself.

Interesting science, a trail of logically iterative research leading to a pleasingly clear result, and there are obvious implications for the findings. It also builds on a broader body of research results that are pointing towards “biomarkers for Parkinson’s”.

Until now, there hasn’t been a test for Parkinson’s (beyond brain imaging that assesses the dopamine turnover in the brain – called DATscan). As discussed in the intro of this post, 2023 has been an exciting year for biomarker research for Parkinson’s, and now Dr Sanders and her team have added to the field with a PCR-based tool that could be incorporated in any laboratory around the world. With numerous biotech companies developing inhibitors of LRRK2 as potential treatments for Parkinson’s, tools that can not only help determine if someone has Parkinson’s, but also assess if a LRRK2 inhibitor is doing what it is supposed to, will be extremely useful going forward.

So, again, watch this space!

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The author of this post is an employee of Cure Parkinson’s, so he might be a little bit biased in his views on research and clinical trials supported by the trust. That said, the trust has not requested the production of this post, and the author is sharing it simply because it may be of interest to the Parkinson’s community.

The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

In addition, many of the companies mentioned in this post are publicly traded companies. That said, the material presented on this page should under no circumstances be considered financial advice. Any actions taken by the reader based on reading this material is the sole responsibility of the reader. None of the companies have requested that this material be produced, nor has the author had any contact with any of the companies or associated parties. This post has been produced for educational purposes only.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Nature

4 thoughts on “Exploring the damage of mtDNA”