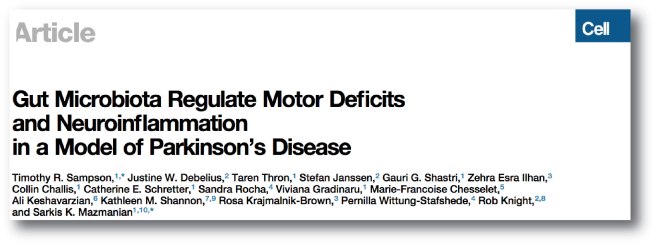

In the world of scientific research, if you publish your research in one of the top peer-reviewed journals (eg. Cell, Nature, or Science) that means that it is pretty important stuff.

This week a research report was published in the journal Cell, dealing with the bacteria in our gut and Parkinson’s disease. If it is replicated and confirmed, it will most certainly be considered REALLY ‘important stuff’.

In today’s post we review what the researchers found in their study.

Bacteria in the gut. Source: Huffington Post

Although we may think of ourselves as individuals, we are not.

We are host to billions of microorganisms. Ours bodies are made up of microbiomes – that is, collections of microbes or microorganisms inhabiting particular environments and creating “mini-ecosystems”. Most of these bacteria have very important functions which help to keep us healthy and functioning normally. Without them we would be in big trouble.

One of the most important microbiomes in our body is that of the gut (Click here for a nice short review on this topic). And recently there has been a lot of evidence that the microbiome of our gut may be playing a critical role in Parkinson’s disease.

What does the gut have to do with Parkinson’s disease?

We have previously written about the connections between the gut and Parkinson’s disease (see our very first post, and subsequent posts here, here and here), and there are now many theories that this debilitating condition may actually start in the gastrointestinal system. This week a new study was published which adds to the accumulating evidence.

So what does the new study say?

Title: Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease

Authors: Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, Janssen S, Shastri GG, Ilhan ZE, Challis C, Schretter CE, Rocha S, Gradinaru V, Chesselet MF, Keshavarzian A, Shannon KM, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Wittung-Stafshede P, Knight R, Mazmanian SK

Journal: Cell, 167 (6), 1469–1480

PMID: 27912057 (this article is available here)

The researchers (who have previously conducted a great deal of research on the microbiome of the gut and it’s interactions with the host) used mice that have been genetically engineered to produce abnormal amounts of alpha synuclein – the protein associated with Parkinson’s disease (Click here for more on this). They tested these mice and normal wild-type mice on some behavioural tasks and found that the alpha-synuclein producing mice performed worse.

A lab mouse. Source: USNews

The researchers then raised a new batch of alpha-synuclein producing mice in a ‘germ free environment’ and tested them on the same behavioural tasks. ‘Germ free environment’ means that the mice have no microorganisms living within them.

And guess what happened:

The germ-free alpha-synuclein producing mice performed as well as on the behavioural task as the normal mice. There was no difference in the performance of the two sets of mice.

How could this be?

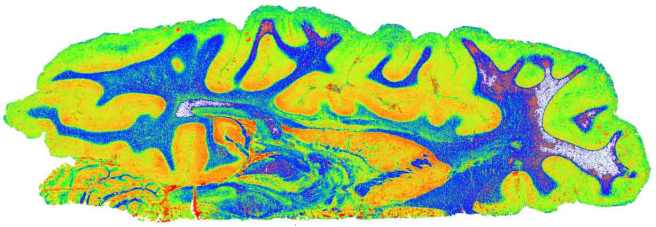

This is what the researchers were wondering, so they decided to have a look at the brains of the mice, where they found less aggregation (clustering or clumping together) of alpha synuclein in the brains of germ-free alpha-synuclein producing mice than their ‘germ-full’ alpha-synuclein producing mice.

This result suggested that the microbiome of the gut may be somehow involved with controlling the aggregation of alpha-synuclein in the brain. The researchers also noticed that the microglia – helper cells in the brain – of the germ-free alpha-synuclein producing mice looked different to their counterparts in the germ-full alpha-synuclein producing mice, indicating that in the absence of aggregating alpha synuclein the microglia were not becoming activated (a key feature in the Parkinsonian brain).

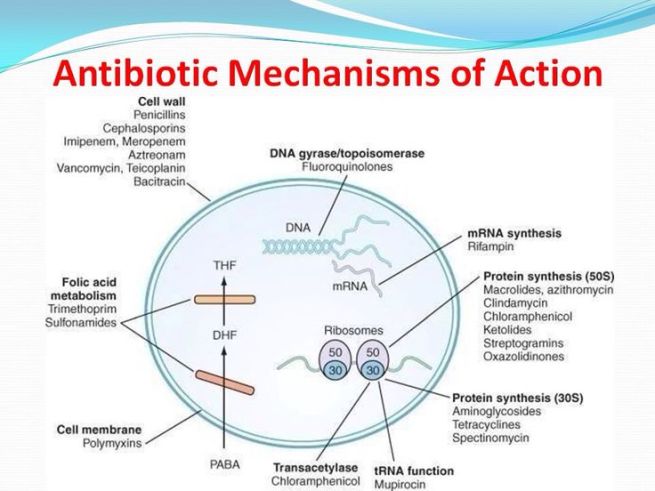

The researchers next began administering antibiotics to see if they could replicate the effects that they were seeing in the germ-free mice. Remarkably, alpha-synuclein producing mice injected with antibiotics exhibited very little dysfunction in the motor behaviour tasks, and they closely resembling mice born under germ-free conditions.

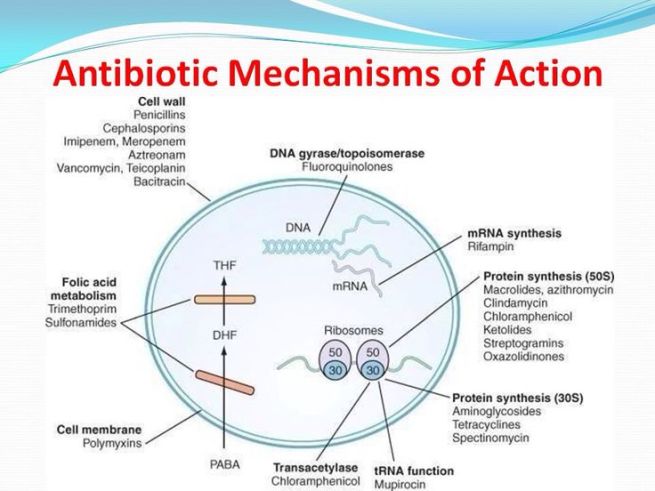

How antibiotics work. Source: MLB

Antibiotics kill bacteria via many different mechanisms (eg. disrupting the cell membrane or targeting protein synthesis; see image above), and they have previously demonstrated efficacy in models of Parkinson’s disease. We shall come back to this in a section below.

The researchers in the study next asked if the microbiome of people with Parkinson’s disease could affect the behaviour of their germ free mice. They took samples of gut bacteria from 6 people who were newly diagnosed (and treatment naive) with Parkinson’s disease and from 6 healthy age matched control samples. These samples were then injected into the guts of germ free mice… and guess what happened.

The germ-free mice injected with gut samples from Parkinsonian subjects performed worse on the behavioural tasks than those injected with samples from healthy subjects. This finding suggested that the gut microbiome of people with Parkinson’s disease has the potential to influence vulnerable mice.

Note the wording of that last sentence.

Importantly, the researchers noted that when they attempted this experiment in normal mice they observed no difference in the behaviour of the mice regardless of which gut samples were injected (Parkinsonian or healthy). This suggests that an abundance of alpha synuclein is required for the effect, and that the microbiome of the gut is exacerbating the effect.

So what does it all mean?

If it can be replicated (and there will now be a frenzy of research groups attempting this), it would be a BIG step forward for the field of Parkinson’s disease research. Firstly, it could represent a new and more disease-relevant model of Parkinson’s disease with which drugs can be tested (it should be noted however that very little investigation of the brain was made in this study. For example, we have no idea of what the dopamine system looks like in the affected mice – we hope that this analysis is ongoing and will form the results of a future publication).

The results may also explain the some of the environmental factors that are believed to contribute to Parkinson’s disease. Epidemiological evidence has linked certain pesticide exposure to the incidence Parkinson’s disease, and the condition is associated with agricultural backgrounds (for more on this click here). It is important to reinforce here that the researchers behind this study are very careful in not suggesting that Parkinson’s disease is starting in the gut, merely that the microbiome may be playing a role in the etiology of this condition.

The study may also mean that we should investigate novel treatments focused on the gut rather than the brain. This approach could involve anything from fecal transplants to antibiotics.

EDITORIAL NOTE HERE: While there are one or two anecdotal reports of fecal transplants having beneficial effect in Parkinson’s disease, they are few and far between. There have never been any comprehensive, peer-reviewed preclinical or clinical studies conducted. Such an approach, therefore, should be considered EXTREMELY experimental and not undertaken without seeking independent medical advice. We have mentioned it here only for the purpose of inserting this warning.

Has there been any research into antibiotics in Parkinson’s disease?

You might be surprised to hear this, but ‘Yes there has’. Numerous studies have been conducted. In particular, this one:

Title: Minocycline prevents nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease.

Author: Du Y, Ma Z, Lin S, Dodel RC, Gao F, Bales KR, Triarhou LC, Chernet E, Perry KW, Nelson DL, Luecke S, Phebus LA, Bymaster FP, Paul SM.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Dec 4;98(25):14669-74.

PMID: 11724929 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this research study, the researchers gave the antibiotic ‘Minocycline’ to mice in which Parkinson’s disease was being modelled via the injection of a neurotoxin that specifically kills dopamine neurons (called MPTP).

Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic that works by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. It has also been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in different models of neurodegeneration via several pathways, primarily anti-inflammatory and inhibiting microglial activation.

The researchers found that Minocycline demonstrated neuroprotective properties in cell cultures so they then tested it in mice. When the researchers gave Minocycline to their ‘Parkinsonian’ mice, they found that it inhibited inflammatory activity of glial cells and thus protected the dopamine cells from dying (compared to control mice that did not receive Minocycline).

Have there been any clinical trials of antibiotic?

Again (surprisingly): Yes.

Title: A pilot clinical trial of creatine and minocycline in early Parkinson disease: 18-month results.

Authors: NINDS NET-PD Investigators..

Journal: Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008 May-Jun;31(3):141-50.

PMID: 18520981 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

This research report was the follow up of a 12 month clinical study that can be found by clicking here. The researchers had taken two hundred subjects with Parkinson’s disease and randomly sorted them into the three groups: creatine (an over-the-counter nutritional supplement), minocycline, and placebo (control). All of the participants were diagnosed less than 5 years before the start of the study.

At 12 months, both creatine and minocycline were noted as not interfering with the beneficial effects of symptomatic therapy (such as L-dopa), but a worrying trend began with subjects dropping out of the minocycline arm of the study.

At the 18 month time point, approximately 61% creatine-treated subjects had begun to take additional treatments (such as L-dopa) for their symptoms, compared with 62% of the minocycline-treated subjects and 60% placebo-treated subjects. This result suggested that there was no beneficial effect from using either creatine or minocycline in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, as neither exhibited any greater effect than the placebo.

Was that the only clinical trial?

No.

Another clinical trial, targeted a particular type of gut bacteria: Helicobacter pylori (which we have discussed in a previous post – click here for more on that).

Title: Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection improves levodopa action, clinical symptoms and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Hashim H, Azmin S, Razlan H, Yahya NW, Tan HJ, Manaf MR, Ibrahim NM.

Journal: PLoS One. 2014 Nov 20;9(11):e112330.

PMID: 25411976 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers recruited 82 people with Parkinson’s disease. A total of 27 (32.9%) of those subjects had positive tests for Helicobacter pylori, and those participants had significantly poorer clinical scores compared to Helicobacter pylori-negative subjects. The researcher gave the participants a drug that kills Helicobacter pylori, and then twelve weeks later the researchers found improvements in levodopa onset time and effect duration, as well as better scores in motor performance and quality of life measures.

The researchers concluded that the screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori is inexpensive and should be recommended for people with Parkinson’s disease, especially those with minimal responses to levodopa. Other experiments suggest that Helicobacter pylori is influencing some people’s response to L-dopa (click here for more on that).

Some concluding thoughts

While we congratulate the authors of the microbiome study published in the journal Cell for an impressive piece of work, we are cautious in approaching the conclusions of the study.

All really good research will open the door to lots of new questions, and the Cell paper published last week has certainly done this. But as we have suggested above, the results need to be independently replicated before we can get to excited about them. So while the media may be making a big fuss about this study, we’ll wait for (and report here) the follow-up, replication studies by independent labs before calling this REALLY ‘important stuff’.

Stay tuned.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from the Huffington Post