Recently the results of a small clinical study looking at Resveratrol in Alzheimer’s disease were published. Resveratrol has long been touted as a miracle ingredient in red wine, and has shown potential in animal models of Parkinson’s disease, but it has never been clinically tested.

Is it time for a clinical trial?

In today’s post we will review the new clinical results and discuss what they could mean for Parkinson’s disease.

From chemical to wine – Resveratrol. Source: Youtube

In 2006, there was a research article published in the prestigious journal Nature about a chemical called resveratrol that improved the health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet (Click here for the press release).

Title: Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet.

Authors: Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA.

Journal: Nature. 2006 Nov 16;444(7117):337-42.

PMID: 17086191 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators placed middle-aged (one-year-old) mice on either a standard diet or a high-calorie diet (with 60% of calories coming from fat). The mice were maintained on this diet for the remainder of their lives. Some of the high-calorie diet mice were also placed on resveratrol (20mg/kg per day).

After 6 months of this treatment, the researchers found that resveratrol increased survival of the mice and insulin sensitivity. Resveratrol treatment also improved mitochondria activity and motor performance in the mice. They saw a clear trend towards increased survival and insulin sensitivity.

The report caused a quite a bit of excitement – suddenly there was the possibility that we could eat anything we wanted and this amazing chemical would safe us from any negative consequences.

Source: Nature

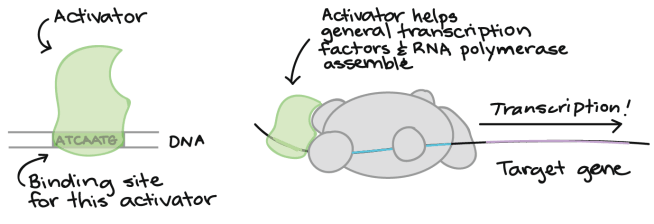

That report was proceeded by numerous studies demonstrating that resveratrol could extend the life-span of various micro-organisms, and it was achieving this by activating a family of genes called sirtuins (specifically Sir1 and Sir2) (Click here, here and here for more on this).

Subsequent to these reports, there have been numerous scientific publications suggesting that resveratrol is capable of all manner of biological miracles.

Wow! So what is resveratrol?

Do you prefer your wine in pill form? Source: Patagonia

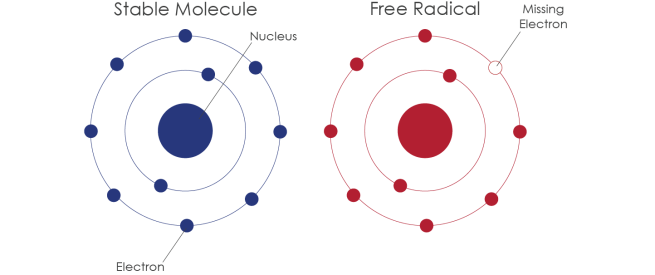

Resveratrol is a chemical that belongs to a group of compounds called polyphenols. They are believed to act like antioxidants. Numerous plants produce polyphenols in response to injury or when the plant is under attack by pathogens (microbial infections).

Fruit are a particularly good source of resveratrol, particularly the skins of grapes, blueberries, raspberries, mulberries and lingonberries. One issue with fruit as a source of resveratrol, however, is that tests in rodents have shown that less than 5% of the oral dose was observed as free resveratrol in blood plasma (Source). This has lead to the extremely popular idea of taking resveratrol in the form of wine, in the hope that it could have higher bioavailability compared to resveratrol in pill form. Red wines have the highest levels of Resveratrol in their skins (particularly Mabec, Petite Sirah, St. Laurent, and pinot noir). This is because red wine is fermented with grape skins longer than is white wine, thus red wine contains more resveratrol.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Sorry to rain on the parade, but it is important to note here that red wine actually contains only small amounts of resveratrol – less than 3-6 mg per bottle of red wine (750ml). Thus, one would need to drink a great deal of red wine per day to get enough resveratrol (the beneficial effects observed in the mouse study described above required 20mg/kg of resveratrol per day. For a person weighting 80kg, this would equate to 1.6g per day or approximately 250 750ml bottles).

We would like to suggest that consuming red wine would NOT be the most efficient way of absorbing resveratrol. And obviously we DO NOT recommend any readers attempt to drink 250 bottles per day (if that is even possible).

The recommended daily dose of resveratrol should not exceed 250 mg per day over the long term (Source). Resveratrol might increase the risk of bleeding in people with bleeding disorders. And we recommend discussing any change in treatment regimes with your doctor before starting.

So what did they find in the Alzheimer’s clinical study?

Well, the report we will look at today is actually a follow-on to published results from a phase 2/safety clinical trial that were reported in 2015:

Title: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease.

Authors: Turner RS, Thomas RG, Craft S, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Reynolds BA, Brewer JB, Rissman RA, Raman R, Aisen PS; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study.

Title: Neurology. 2015 Oct 20;85(16):1383-91.

PMID: 26362286 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers behind the study are associated with the Georgetown research group that conducted the initial Nilotinib clinical study in Parkinson’s disease (Click here for our post on this).

The investigators conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-center phase 2 trial of resveratrol in individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. The study lasted 52 weeks and involved 119 individuals who were randomly assigned to either placebo or resveratrol 500 mg orally daily treatment.

EDITOR’S NOTE: We appreciate that is daily dose exceeds the recommended daily dose mentioned above, but it is important to remember that the participants involved in this study were being closely monitored by the study investigators.

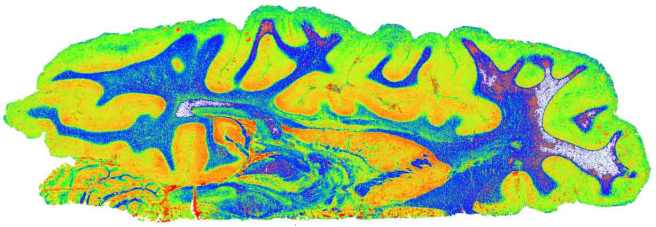

Brain imaging and samples of cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid within which the brain sits) were collected at the start of the study and after completion of treatment.

The most important result of the study was that resveratrol was safe and well-tolerated. The most common side effect was feeling nausea and diarrhea in approximately 42% of individuals taking resveratrol (curiously 33% of the participants blindly taking the placebo reported the same thing). There was also a weight loss effect between the groups, with the placebo group gaining 0.5kg on average, while the resveratrol treated group lost 1kg on average.

The second important take home message is that resveratrol crossed the blood–brain barrier in humans. The blood brain barrier prevents many compounds from having any effect in the brain, but it does not stop resveratrol.

The investigators initially found no effects of resveratrol treatment in various Alzheimer’s markers in the cerebrospinal fluid. Not did they see any effect in brain scans, cognitive testing, or glucose/insulin metabolism. The authors were cautious about their conclusions based on these results, however, as the study was statistically underpowered (that is to say, there were not enough participants in the various groups) to detect clinical benefits. They recommended a larger study to determine whether resveratrol is actually beneficial.

While exploring the idea of a larger study, the researchers have re-analysed some of the data, and that brings us to the report we want to review today:

Title: Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease.

Authors: Moussa C, Hebron M, Huang X, Ahn J, Rissman RA, Aisen PS, Turner RS.

Journal: J Neuroinflammation. 2017 Jan 3;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0779-0.

PMID: 28086917 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this report, the investigators conducted a retrospective study re-examining the cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma samples from a subset of subjects involved in the clinical study described above. In this study, they only looked at the subjects who started with very low levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of a protein called Aβ42.

Amyloid beta (or Aβ) is the bad boy/trouble maker of Alzheimer’s disease; considered to be critically involved in the disease. A fragment of this protein (called Aβ42) begin clustering in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and as a result, low levels of Aβ42 in cerebrospinal fluid have been associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and considered a possible biomarker of the condition (Click here to read more on this).

The resveratrol study investigators collected all of the data from subjects with cerebrospinal fluid levels of Aβ42 less than 600 ng/ml at the start of the study. This selection criteria gave them 19 resveratrol-treated and 19 placebo-treated subjects.

In this subset re-analysis study, resveratrol treatment appears to have slowed the decline in cognitive test scores (the mini-mental status examination), as well as benefiting activities of daily living scores and cerebrospinal fluid levels of Aβ42.

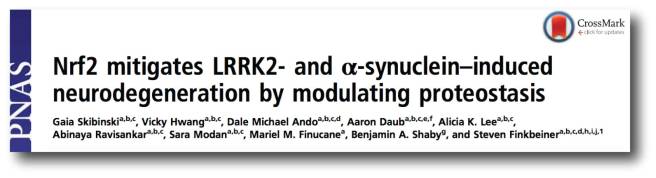

One of the most striking results from this study is the significant decrease observed in the cerebrospinal fluid levels of a protein called Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (or MMP9) after resveratrol treatment. MMP9 is slowly emerged as an important player in several neurodegenerative conditions, including Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more on this). Thus the decline observed is very interesting.

This re-analysis indicates beneficial effects in some cases of Alzheimer’s as a result of taking resveratrol over 52 weeks. The researchers concluded that the findings of this re-analysis support the idea of a larger follow-up study of resveratrol in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Ok, but what research has been done on resveratrol in Parkinson’s disease?

Yes, good question.

One of the earliest studies looking at resveratrol in Parkinson’s disease was this one:

Title: Neuroprotective effect of resveratrol on 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson’s disease in rats.

Authors: Jin F, Wu Q, Lu YF, Gong QH, Shi JS.

Journal: Eur J Pharmacol. 2008 Dec 14;600(1-3):78-82.

PMID: 18940189

In this study, the researchers used a classical rodent model of Parkinson’s disease (using the neurotoxin 6-OHDA). One week after inducing Parkinson’s disease, the investigators gave the animals either a placebo or resveratrol (at doses of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg). This treatment regime was given daily for 10 weeks and the animals were examined behaviourally during that time.

The researchers found that resveratrol improved motor performance in the treated animals, with them demonstrating significant results as early as 2 weeks after starting treatment. Resveratrol also reduced signs of cell death in the brain. The investigators concluded that resveratrol exerts a neuroprotective effect in this model of Parkinson’s disease.

Similar results have been seen in other rodent models of Parkinson’s disease (Click here and here to read more).

Subsequent studies have also looked at what effect resveratrol could be having on the Parkinson’s disease associated protein alpha synuclein, such as this report:

Title: Effect of resveratrol on mitochondrial function: implications in parkin-associated familiarParkinson’s disease.

Authors: Ferretta A, Gaballo A, Tanzarella P, Piccoli C, Capitanio N, Nico B, Annese T, Di Paola M, Dell’aquila C, De Mari M, Ferranini E, Bonifati V, Pacelli C, Cocco T.

Journal: Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Jul;1842(7):902-15.

PMID: 24582596 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators collected skin cells from people with PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease.

What is PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease?

There are about 20 genes that have been associated with Parkinson’s disease, and they are referred to as the PARK genes. Approximately 10-20% of people with Parkinson’s disease have a genetic variation in one or more of these PARK genes (we have discussed these before – click here to read that post).

PARK2 is a gene called Parkin. Mutations in Parkin can result in an early-onset form of Parkinson’s disease. The Parkin gene produces a protein which plays an important role in removing old or sick mitochondria.

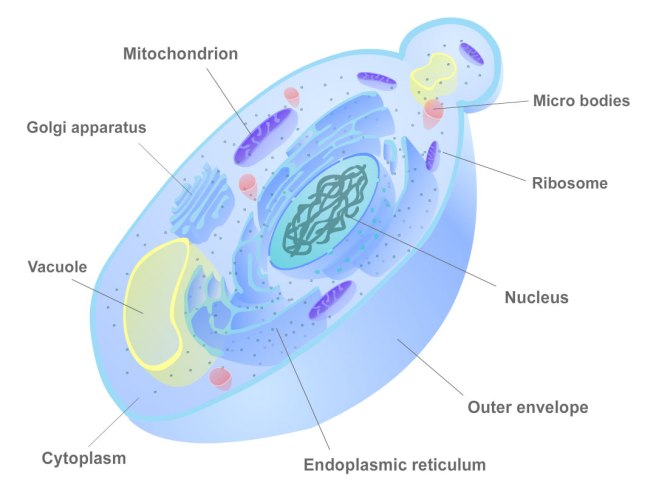

Hang on a second. Remind me again: what are mitochondria?

We have previously written about mitochondria (click here to read that post). Mitochondria are the power house of each cell. They keep the lights on. Without them, the lights go out and the cell dies.

Mitochondria and their location in the cell. Source: NCBI

You may remember from high school biology class that mitochondria are bean-shaped objects within the cell. They convert energy from food into Adenosine Triphosphate (or ATP). ATP is the fuel which cells run on. Given their critical role in energy supply, mitochondria are plentiful and highly organised within the cell, being moved around to wherever they are needed.

Another Parkinson’s associated protein, Pink1 (which we have discussed before – click here to read that post), binds to dysfunctional mitochondria and then grabs Parkin protein which signals for the mitochondria to be disposed of. This process is an essential part of the cell’s garbage disposal system.

Park2 mutations associated with early onset Parkinson disease cause the old/sick mitochondria are not disposed of correctly and they simply pile up making the cell sick. The researchers that collected the skin cells from people with PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease found that resveratrol treatment partially rescued the mitochondrial defects in the cells. The results obtained from these skin cells derived from people with early-onset Parkinson’s disease suggest that resveratrol may have potential clinical application.

Thus it would be interesting (and perhaps time) to design a clinical study to test resveratrol in people with PARK2 associated Parkinson’s disease.

So why don’t we have a clinical trial?

Resveratrol is a chemical that falls into the basket of un-patentable drugs. This means that big drug companies are not interested in testing it in an expensive series of clinical trials because they can not guarantee that they will make any money on their investment.

There was, however, a company set up in 2004 by the researchers behind the original resveratrol Nature journal report (discussed at the top of this post). That company was called “Sirtris Pharmaceuticals”.

Source: Crunchbase

Sirtris identified compounds that could activate the sirtuins family of genes, and they began testing them. They eventually found a compound called SRT501 which they proposed was more stable and 4 times more potent than resveratrol. The company went public in 2007, and was subsequently bought by the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline in 2008 for $720 million.

Source: Xconomy

From there, however, the story for SRT501… goes a little off track.

In 2010, GlaxoSmithKline stopped any further development of SRT501, and it is believed that this decision was due to renal problems. Earlier that year the company had suspended a Phase 2 trial of SRT501 in a type of cancer (multiple myeloma) because some participants in the trial developed kidney failure (Click here to read more).

Then in 2013, GlaxoSmithKline shut down Sirtris Pharmaceuticals completely, but indicated that they would be following up on many of Sirtris’s other sirtuins-activating compounds (Click here to read more on this).

Whether any of those compounds are going to be tested on Parkinson’s disease is yet to be determined.

What we do know is that the Michael J Fox foundation funded a study in this area in 2008 (Click here to read more on this), but we are yet to see the results of that research.

We’ll let you know when we hear of anything.

So what does it all mean?

Summing up: Resveratrol is a chemical found in the skin of grapes and berries, which has been shown to display positive properties in models of neurodegeneration. A recent double blind phase II efficacy trial suggests that resveratrol may be having positive benefits in Alzheimer’s disease.

Preclinical research suggests that resveratrol treatment could also have beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease. It would be interesting to see what effect resveratrol would have on Parkinson’s disease in a clinical study.

Perhaps we should have a chat to the good folks at ‘CliniCrowd‘ who are investigating Mannitol for Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more about this). Maybe they would be interested in resveratrol for Parkinson’s disease.

ONE LAST EDITOR’S NOTE: Under absolutely no circumstances should anyone reading this material consider it medical advice. The material provided here is for educational purposes only. Before considering or attempting any change in your treatment regime, PLEASE consult with your doctor or neurologist. SoPD can not be held responsible for actions taken based on the information provided here.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from VisitCalifornia