In October, 40,000 neuroscientists from all over the world gathered in Chicago for the annual Society for Neuroscience conference. It is one of the premier events on the ‘brain science’ calendar each year and only a few cities in the USA have the facilities to handle such a huge event.

Science conference. Source: JPL

During the five day neuroscience marathon, hundreds of lecture presentations were made and thousands of research poster were exhibited. Many new and exciting findings were presented to the world for the first time, including the results of an interesting pilot study that has left everyone in the Parkinson’s research community very excited, but also scratching their heads.

The study (see the abstract here) was a small clinical trial (12 subjects; 6 month study) that was aiming to determine the safety and efficacy of a cancer drug, Nilotinib (Tasigna® by Novartis), in advanced Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy body dementia patients. In addition to checking the safety of the drug, the researchers also tested cognition, motor skills and non-motor function in these patients and found 10 of the 12 patients reported meaningful clinical improvements.

The study investigators reported that one individual who had been confined to a wheelchair was able to walk again; while three others who could not talk before the study began were able to hold conversations. They suggested that participants who were still in the early stages of the disease responded best, as did those who had been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

So what is Nilotinib?

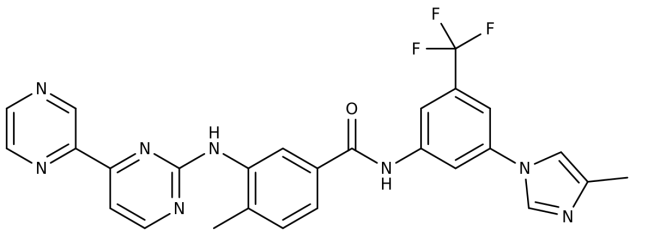

Nilotinib (pronounced ‘nil-ot-in-ib’ and also known by its brand name Tasigna) is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor, that has been approved for the treatment of imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). That is to say, it is a drug that can be used to treat a type of leukemia when the other drugs have failed. It was approved for this treating cancer by the FDA in 2007.

The researchers behind the study suggest that Nilotinib works by turning on autophagy – the “garbage disposal machinery” inside each neuron. Autophagy is a process that clears waste and toxic proteins from inside cells, preventing them from accumulating and possibly causing the death of the cell.

The process of autophagy – Source: Wormbook

Waste material inside a cell is collected in membranes that form sacs (called vesicles). These vesicles then bind to another sac (called a lysosome) which contains enzymes that will breakdown and degrade the waste material.

Some details about the study:

- The study was run at the Georgetown University Medical Center

- The patients were given increasing doses of Nilotinib (150mg to 300mg/day) that were are significantly lower than the doses of Nilotinib used for CML treatment (800-1200mg/day).

- The researchers took cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; the liquid surrounding the brain) and blood samples at the start of the study, 2 and 6 months into the study.

- Nilotinib was detected in the CSF, indicating that it had no problem crossing the protective blood-brain-barrier – the membrane covering the brain that blocks many drugs from entering.

- Participants exhibited positive changes in various cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers with statistically significant changes in an important protein called, Tau, which have been shown to increase with the onset of dementia.

- The researchers found a significant reduction (>60%) in levels of α-Synuclein detected in the blood, but no change in CSF levels of α-Synuclein.

- The investigators report that one individual confined to a wheelchair was able to walk again; three others who could not talk were able to hold conversations.

If the outcomes of this study are reproducible, then we here at the Science of Parkinson’s are assuming that Nilotinib is working by turning on the garbage disposal system of the remaining cells in the brain and allowing them to function better. This would suggest that there is a certain level of dysfunction in those remaining cells, which would be expected as this is a progressive disease. The study researchers reported that the small, daily dose of nilotinib turns on autophagy for about four to eight hours, and if that is enough to have such remarkable effects, then this treatment deserves more research.

The results of the study are intriguing and the participants of the study will continue to be treated and followed to see if the improvements continue.

BUT before we go getting too excited:

While these results sound extremely positive, there are several issues with this study that need to be considered before we celebrate the end of Parkinson’s disease.

Firstly, this study was an open-label trial – that means that everyone involved in the study (both researchers and subjects) knew what drug they were taking. There was also no control group or control treatment for comparative analysis in the study. Given these conditions there is always the possibility that what some of the subjects were experiencing was simply a placebo effect. Indeed the lead scientist on the project, Dr Fernando Pagan, pointed out that “It is critical to conduct larger and more comprehensive studies before determining the drug’s true impact.”

In addition, according to Novartis (the producer of the drug), the current cost of Nilotinib is about $10,360 (£6,900) per month for the daily 800mg dose used for cancer treatment. Even if the dose used in this study was only 150 to 300 mg/daily, it would still make this treatment extremely expensive.

Thirdly, Nilotinib has a number of adverse side-effects when used as an anti-cancer drug (at 800mg/day). These include headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, muscle/joint pain, skin issues, flu-like symptoms, and reduced blood cell count. It may not be the nicest of treatments to tolerate.

There are important reasons for optimism, however, with the results of this study:

In 2010, a group of researchers published a paper demonstrating the neuroprotective effects of another cancer drug very similar to Nilotinib. That drug was ‘Gleevec’

Title: Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin’s ubiquitination and protective function.

Authors: Ko HS, Lee Y, Shin JH, Karuppagounder SS, Gadad BS, Koleske AJ, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC,Dawson VL, Dawson TM.

Journal: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Sep 21;107(38):16691-6.

PMID: 20823226

And that Gleevec publication was followed up a couple of years ago with a second study demonstrating the neuroprotective effects of another Abl-inhibitor: Nilotinib!

Title: The c-Abl inhibitor, nilotinib, protects dopaminergic neurons in a preclinical animal model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Karuppagounder SS, Brahmachari S, Lee Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ko HS

Journal: Sci Rep. 2014 May 2;4:4874.

PMID: 24786396

These studies provided a strong rationale for testing brain permeable c-Abl inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of PD. The phase 2 trial at Georgetown will be starting in early 2016 and we will be watching this trial very closely.