We have previously discussed news briefings regarding a cancer drug that displayed interesting results in a pilot clinical study of Parkinson’s disease (click here to read that post). Today we will delve more deeply into the results of that particular study and consider what they mean.

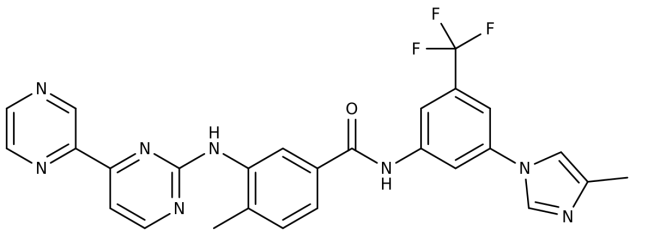

Nilotinib (Tasigna) from Novartis. Source: William-Jon

In October of last year, at the Society for Neuroscience meeting in Chicago, a presentation of data from a clinical trial got the Parkinson’s community really excited. The study was investigating the effects of a cancer drug called ‘Nilotinib’ (also known as Tasigna) on Parkinson’s disease and the initial results were rather interesting.

The results of the pilot clinical study for Nilotinib were published today in the Journal of Parkinson’s disease:

Title: Nilotinib Effects in Parkinson’s disease and Dementia with Lewy bodies

Authors: Pagan F, Hebron M, Valadez E, Tores-Yaghi Y,Huang X, Mills R, Wilmarth B, Howard H, Dunn C, Carlson A, Lawler A, Rogers S, Falconer R, Ahn J, Li Z, & Moussa C.

Journal: Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, vol. Preprint

PMID: Yet to be allocated (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it).

The study was setup to determine safety of using Nilotinib in Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies.

What is Nilotinib?

Nilotinib is a drug that can be used to treat a type of leukemia when the other cancer drugs have failed. It was approved for this treating cancer by the FDA in 2007.

The researchers behind the current study believe that Nilotinib works by turning on autophagy – the “garbage disposal machinery” inside brain cells. Autophagy is a process that clears waste and toxic proteins from inside cells, preventing them from accumulating and possibly causing the death of the cell.

The process of autophagy – Source: Wormbook

Waste material inside a cell is collected in membranes that form sacs (called vesicles). These vesicles then bind to another sac (called a lysosome) which contains enzymes that will breakdown and degrade the waste material.

The researchers suggest that Nilotinib may be working in Parkinson’s disease by helping affected cells to better clear away the build up of unnecessary proteins, which helps cells to function more efficiently.

What happened in the clinical study?

Twelve people with either Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies were randomized given either 150 mg (n = 5) or 300 mg (n = 7) daily doses of Nilotinib for 24 weeks. After the treatment period the subjects were followed up for 12 weeks. All of the subjects were considered to have mid to late stage Parkinson’s features (Hoehn and Yahr stage 3–5). One subject was withdrawn from the study at week 4 due to a heart attack and another discontinued at 5 months due to unrelated circumstances.

An important question in the study was whether Nilotinib could actually enter the brain. Various tests conducted on the subjects suggesting that the drug had no problem crossing the ‘blood brain barrier‘ and having an effect in the brain. The levels of Nilotinib in the brain peaked at 2 hrs after taking the drug and the levels of the target protein (called p-Abl) were reduced by 30% at 1 hr. This level of activity remained stable for several hours.

The motor features of Parkinson’s disease were assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and the investigators observed an average decrease of 3.4 points and 3.6 points at six months (week 24) compared to the baseline measures (scores from the start of the study) with 150 mg and 300 mg Nilotinib, respectively. A decrease in motor scores represent a reduction in Parkinson’s motor features.

The really remarkable result, however, comes from the testing of cognitive performance, which was monitored with Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE). The researchers report an average increase of 3.85 and 3.5 points in MMSE at six months (24-week) compared to baseline, for 150 mg and 300 mg of Nilotinib, respectively. This means that the mental processing of the subjects improved across the study.

The motor and cognitive results were complemented by measures of proteins in blood and cerebrospinal fluid samples taken from the subjects. The researchers saw increases in dopamine related proteins (suggesting that more dopamine was present in the brain) and stabilization of alpha synuclein levels.

The researchers concluded that these observations warrant a larger randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to truly evaluate the safety and efficacy of Nilotinib.

Here at the SoPD, we are inclined to agree.

So what does all this mean?

The results of the study are very interesting, and the researchers should be congratulated on the outcome (and presentation of all the data in the report). As they themselves acknowledge, the study was open labelled – meaning that everyone in the study knew that they were getting the treatment – so the placebo effect could be at play here.

One intriguing note in the report was that most of the participants in the study ‘experienced increased psychotic symptoms (hallucination, paranoia, agitation) and some dyskinesia whilst on Nilotinib’ suggesting an increase in dopamine levels in the brain.

Obviously a larger, double-blind study is required to determine whether the effect of the drug in Parkinson’s disease is real. The Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Van Andel Research Institute (Michigan, USA) and the Cure Parkinson’s Trust are collaborating on the development program for a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of nilotinib, which it is hoped will begin in 2017.

The banner for today’s banner was sourced from Wikimedia

Archimedes. Source: Lecturesbureau

Archimedes. Source: Lecturesbureau Source: Actioncoach

Source: Actioncoach