|

In 2017, a research report suggested that people taking the asthma treatment Salbutamol had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s. In addition, that same study suggested that another medication called Propranolol – which is used for hypertension/high blood pressure – increased ones risk of developing Parkinson’s. Both drugs work via a molecule called the Beta2 adrenoreceptor. The study caused a lot of excitement, and clinical studies were even proposed. Now, however, new research suggests that these associations may not actually exist and those clinical trial plans will be need to be put on standby. In today’s post we will discuss what the Beta2 adrenoreceptor is, how these two drugs (Salbutamol and Propranolol) affect it, and look at what the new results suggest.

|

Saul Goodman. Source: Amc

There is a popular show on Netflix called ‘Better call Saul’ (the title of this post is a play on the name).

It chronicles the life of a lawyer – named Saul Goodman – who struggles to make his way in the grey world of the law profession. He fights to survive by taking the information he has, and using it to plead his cases. But sometimes the original pieces of information he is dealing with are not always what they appear to be.

A similar situation faces researchers the world over.

Every day new information is reported. And this process is unrelenting. It simply never stops.

For Parkinson’s research alone, every day there is about 20 new research reports (approximately 120 per week).

But determining what is ‘usable’ information relies on independent replication. And sometimes efforts to validate a new finding fail to reproduce the initially reported results.

An example of this has occurred recently in the world of Parkinson’s research, with some rather large implications.

What happened?

Last year (2017), this research report was published:

Title: β2-Adrenoreceptor is a regulator of the α-synuclein gene driving risk of Parkinson’s disease

Title: β2-Adrenoreceptor is a regulator of the α-synuclein gene driving risk of Parkinson’s disease

Authors: Mittal S, Bjørnevik K, Im DS, Flierl A, Dong X, Locascio JJ, Abo KM, Long E, Jin M, Xu B, Xiang YK, Rochet JC, Engeland A, Rizzu P, Heutink P, Bartels T, Selkoe DJ, Caldarone BJ, Glicksman MA, Khurana V, Schüle B, Park DS, Riise T, Scherzer CR.

Journal: Science. 2017 Sep 1;357(6354):891-898.

PMID: 28860381

The researchers who conducted this study began by conducting a massive screening experiment. They wanted to identify drugs that could reduce the production of a protein called Alpha Synuclein (regular readers will be aware that that protein is intimately associated with Parkinson’s). So the investigators grew cells that stably produce the human version of Alpha Synuclein and they screened 1126 compounds (including drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (or FDA) as well as wide range of natural products, vitamins, health supplements, and alkaloids.

From this screen they identified 35 compounds that lowered Alpha Synuclein levels by more than 35%. Amongst these 35 compounds was the selective Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist metaproterenol. Because metaproterenol is not brain penetrant – meaning that it can not pass through the protective blood-brain-barrier membrane surrounding the brain – the investigators added six related drugs, including the two selective Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists, clenbuterol and salbutamol (which are both brain penetrant).

Hang on a second, what are Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist?

An agonist is a drug that binds to and activates a particular receptor.

What is a receptor?

On the surface of a cell, there are lots of small molecules (called receptors) which act as switches for certain biological processes to be initiated. Receptors will wait for a protein to come along and bind to them, either activating them or alternatively blocking them (not allowing the biological process to be initiated).

The activators are called agonists, while the blockers are antagonists.

Agonist vs antagonist. Source: Psychonautwiki

Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist are drugs that bind to and activate the Beta2-Adrenergic receptor. These receptors sit in the wall of cells (the membrane), with part of themselves exposed to the world outside the cells (the extracellular space) and another region of themselves exposed to the interior of the cell (the intracellular space).

The Beta2-Adrenergic receptor. Source: Wikipedia

Beta2-Adrenergic receptor interacts with a chemical called epinephrine, which is a neurotransmitter like dopamine. Epinephrine will come floating along, bind to the Beta2-Adrenergic receptor, and activate it.

Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists are very similar to epinephrine.

And what medical conditions are treated with Beta2-adrenoreceptor agonists?

They are primarily used to treat pulmonary disorders – that is, conditions of the lungs such as asthma (a common long-term inflammatory condition of the lungs) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (or COPD, which is a progressive obstructive lung disease).

Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists cause smooth muscle fibres to relax.

Ok, so these researchers found Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists reduce the production of Alpha Synuclein in their screening experiment?

Yes, exactly. The cells treated with Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists generated less of the Parkinson’s associated protein alpha synuclein.

One other interesting compound that the screen also highlighted was a drug called Riluzole. This is an FDA-approved drug for modification of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), but it has also been shown to reduce dopaminergic neurodegeneration and provide neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more).

The researchers next injected some mice with Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists and then looked at the dopamine neurons in the brain, and they found that those cells also produced less Alpha Synuclein. Interestingly, they also noted that in genetically engineered mice which did not produce any Beta2-Adrenergic receptors, the levels of Alpha Synuclein in the brain were twice as high as normal.

Interesting. But is all of this relevant to humans?

Well, having established that Beta2-Adrenergic receptor activation reduces Alpha Synuclein levels, the researchers next wanted to turn their attention to what is happening in people that have been treated with Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists. To do this, the researchers used the Norwegian Prescription Database which contains the complete records of all prescribed drugs dispensed at pharmacies to every individual in Norway since 2004 (population: 5 million!).

Norway. Source: Go-today

They decided to look for prescriptions of the Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist, Salbutamol to see whether use of this drug could reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Amazingly, they found that Salbutamol was associated with decreased risk of developing Parkinson’s – literally, a 1/3 reduction in risk (in a dose dependent fashion).

And after noting this, the researchers asked the reverse question: does blocking Beta2-Adrenergic receptor (with an antagonist drug) increase one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s?

And guess what they found?

Drum roll please!

Propranolol is often called a ‘beta-blocker’ because it blocks the Beta2-Adrenergic receptor.

This Beta2-Adrenoreceptor antagonist is commonly used to treat high blood pressure and essential tremor (please note this second condition – it will be important in our discussion further below).

In their analysis, the researchers found that Propranolol was associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of developing Parkinson’s! This result suggested that Beta2-Adrenergic receptor antagonists could be increasing the risk of Parkinson’s.

Source: Science

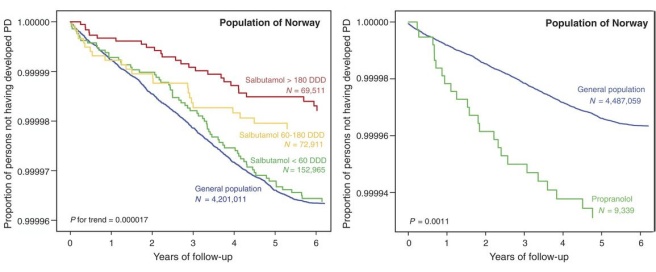

As you can see from the image above, those individuals who took a high defined daily doses (DDD) of Salbutamol (the red line on the left graph) had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s than those who were administered low levels of Salbutamol (the green line – which does not differ from the general population level of risk (blue line)). And on the graph on the right the 9,339 individuals treated with Propranolol (green line) had a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s than the general population.

Wow! This is amazing.

Indeed. And the Parkinson’s research community got very excited – so much so, that neuroprotective clinical trials with Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists (like Salbutamol) are now being considered. But those clinical efforts have been waiting for confirmation of the results before proceeding.

And, um…

Well,…

Have we seen confirmation results?

An attempt at confirming the association between Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists/antagonists and Parkinson’s has recently been reported… but those clinical trials may have to be put on hold as a result.

Huh? What you talkin’ about?

Recently this report was published:

Title: ß2-adrenoreceptor medications and risk of Parkinson disease

Authors: Searles Nielsen S, Gross A, Camacho-Soto A, Willis AW, Racette BA.

Journal: Ann Neurol. 2018 Sep 17. [Epub ahead of print]

PMID: 30225948

In this study, the researchers conducted a case-control study using Medicare data from the United States.

The medical data used was from U.S. residents (aged 66–90 years of age) who used Medicare for health insurance between 2004-2009.

The investigators assessed the Parkinson’s status of each individual using a comprehensive criteria of medicare claims (specifically: inpatient, skilled nursing facility, outpatient, physician/carrier, durable medical equipment, and

home health care) and at least one International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-

9) diagnosis code for Parkinson’s (332 or 332.0) in 2009 (with no previous codes for Parkinson’s, atypical parkinsonism (ICD-9 333.0), or dementia with Lewy bodies (ICD-9 331.82).

This criteria gave the researchers 48,295 cases of Parkinson’s (average age 78.6 years at diagnosis).

They matched these cases with a random sample of 52,324 beneficiaries who met the same criteria, but without any of the ICD-9 codes mentioned above (332, 332.0, 333.0 & 331.82).

What did they do next?

They examined all of these medical records for the use of selected Beta2-Adrenoreceptor antagonists (propranolol, carvedilol, metoprolol) and the Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist salbutamol.

And what did they find?

Well, initially the investigators found that Propranolol did indeed increase the risk of Parkinson’s (odds ratio = 3.62 (95%=3.31-3.96)).

BUT (and it’s a BIG ‘but’) when the researchers adjusted the data to take account the treatment of tremor (during 18 months prior to diagnosis), they found no association between Propranolol use and Parkinson’s (odds ratio = 0.94 (95%=0.80–1.11)).

What does that mean?

Above, I mentioned that Propranolol is used for the treatment of essential tremor. It is used for many kinds of tremor.

And in their analysis, the researchers conducting the new study were wondering if the treatment of tremor may be biasing their analysis. Perhaps, the onset of tremor during the Parkinson’s ‘prodromal’ phase (the period of time immediately before diagnosis) may have lead to doctors prescribing propranolol to treat it. This use of the drug could have led to a false-positive association with Parkinson’s.

So the researchers adjusted their dataset to account for anyone who was prescribed propranolol 18 months prior to their diagnosis of Parkinson’s. When these individuals were removed from the data, the investigators found no association between propranolol use and Parkinson’s.

Interestingly, there was no evidence of an increase in Parkinson’s risk among users of the other common Beta-Adrenoreceptor antagonists (such as carvedilol and metoprolol). And this was true with or without adjusting for tremor, which suggests that the only Beta2-Adrenoreceptor antagonist possibly associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s, was also the one most frequently used to treat tremor (and this association was lost when the data was adjusted for tremor).

This data brings into question the whole idea that Beta2-Adrenoreceptor antagonists are associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s.

Interesting. What about salbutamol?

In this new study, the researchers found that use of salbutamol and other inhaled corticosteroids were associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s.

But (and again, it’s a BIG ‘but’) the researchers were curious about the impact smoking may have on this association.

Smoking is associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s (Click here to read a very old SoPD post on this), and smoking-related pulmonary conditions are often treated with salbutamol. Thus, the researchers were wondering if salbutamol may be being connected with the protective effect of smoking, rather than salbutamol actually having any protective effect itself.

So the investigators separated ‘smokers’ from ‘non-smokers’, and found that salbutamol use in non-smokers had no association with Parkinson’s (it did not increase or decrease risk).

Bummer.

Yeah.

The results of the new study do not deal with the alpha synuclein findings of the previous study. The new study simply failed to find an association between Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists and antagonists with Parkinson’s. The effect of Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists/antagonists on alpha synuclein still need to be replicated.

So what does it all mean?

This is one of those situations where the replication of a really interesting finding has failed to occur.

And this one is particularly disappointing as there were big plans to test salbutamol in clinical trials for its ability to slow the progression of Parkinson’s. Failure to replicate the initial association will lead to a delay of those clinical efforts (at least until someone can replication the original findings).

Unfortunately, this is how science works: first you have a discovery, followed by independent replication, which leads to progress. It is a slow system. Slowed even further when the analysis of data leads to potential false positives.

It will be interesting to see which way future replication studies go with regards to the possible associations between Beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonists/antagonists (and the alpha synuclein effect). But this story should also serve as a warning to folks not to rush in when a new finding is reported. While there is a desperate need for novel therapeutic approaches, it is best to be cautious until data is replicated/validated and thoroughly analysed.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Bookmartialarts

Thanks Simon. Interesting (and mildly disappointing) post. I was hoping for progress on the salbutamol (albuterol here in the US) front. But, as you say, that’s how science works.

I’ve missed your posts lately, but I figured you’d been packing up for a move. Are you at the CPT site yet? Best of luck on your first day.@

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

It is disappointing, but there are a lot of other balls in play at the moment. And some of those other balls are more exciting. This bad news does not slow us down at all. Plus it is good to see such a rapid testing of the previous data.

I have been extremely busy doing things for others recently and the website has been neglected (particularly responding to comments/correspondence). I start tomorrow (1st October) with CPT. Really looking forward to it.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

interesting and cautionary tale. What about Exanetide, does this suffer from the same bias?

Keith

LikeLike

Hi Keith,

I hope all is well. It is a cautionary tale, and it is a good lesson for all – researchers and affected community alike. There is enough independent preclinical research supporting Exenatide that it probably does not fall into the same kind of basket as Salbutamol. But we won’t know for sure until Exenatide III is finished (hopefully starting early 2019). Before then, we will hear about the other GLP-1 agonist (other drugs like Exenatide) clinical trials in Parkinson’s which should give us a flavour of where we stand.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Shoot… thanks as always Simon.

Whatever happened to NIC-PD (nicotine patch) ?

Maybe there is a silver lining.

LikeLike

Hi Double,

Yeah, sorry to be the bearer of bad news.

As for NIC-PD, there has been no updates on the clinicaltrials.gov website since 2015 for this study (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01560754) so I am not sure what is happening with it. I will do some investigating.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi,

What about this article?

Gronich et al. β2-Adrenoceptor Agonists and Antagonists and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. Movement disorders, vol 33, no. 9; Sep 2018.

Also, the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties of b2-AR are ignored.

LikeLike

Hi Monika,

Thanks for your comment. Yes, I am aware of the Gronich et al (2018) report (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30311974) which also finds an association between beta agonists and reduce risk of Parkinson’s – thus supporting the original Mittal study involving the Norwegian data. I am awaiting some further data that is in the peer-review process at the moment before writing another post on this topic.

And yes, there is some data regarding the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties of beta agonists.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike