|

Trehalose is a small molecule – nutritionally equivalent to glucose – that helps to prevent protein from aggregating (that is, clustering together in a bad way).

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition that is characterised by protein aggregating, or clustering together in a bad way.

Is anyone else thinking what I’m thinking?

In today’s post we will look at what trelahose is, review some of the research has been done in the context of Parkinson’s disease, and discuss how we should be thinking about assessing this molecule clinically.

|

Neuropathologists examining a section of brain tissue. Source: Imperial

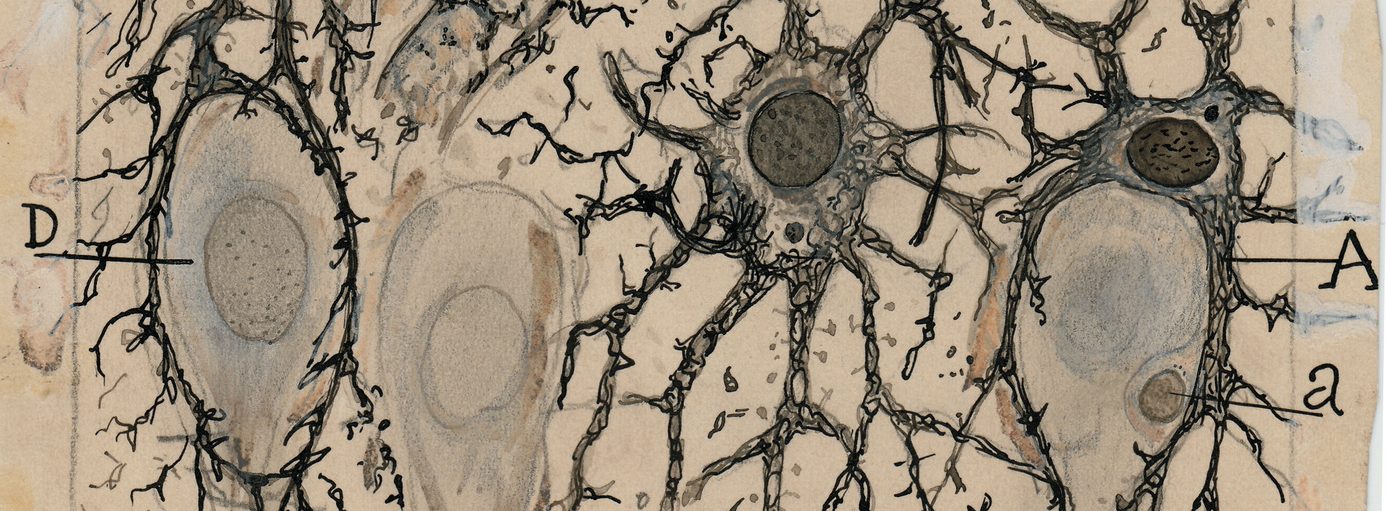

When a neuropathologist makes an examination of the brain of a person who passed away with Parkinson’s, there are two characteristic hallmarks that they will be looking for in order to provide a definitively postmortem diagnosis of the condition:

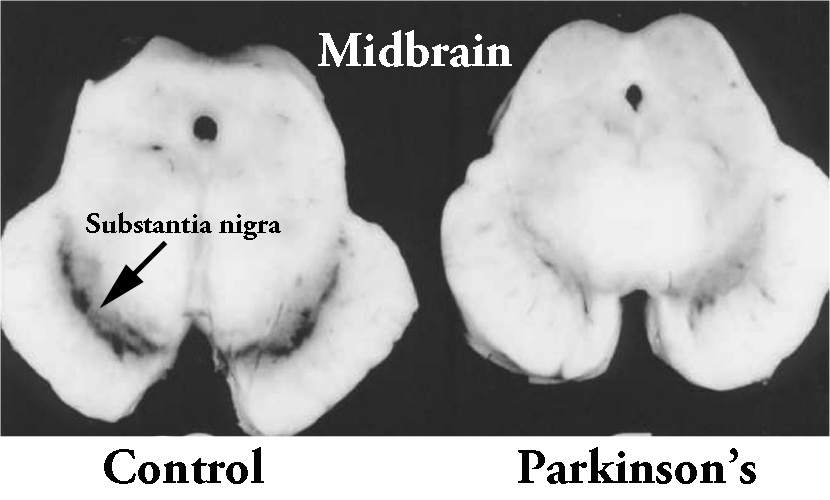

1. The loss of dopamine producing neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra.

The dark pigmented dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source:Memorangapp

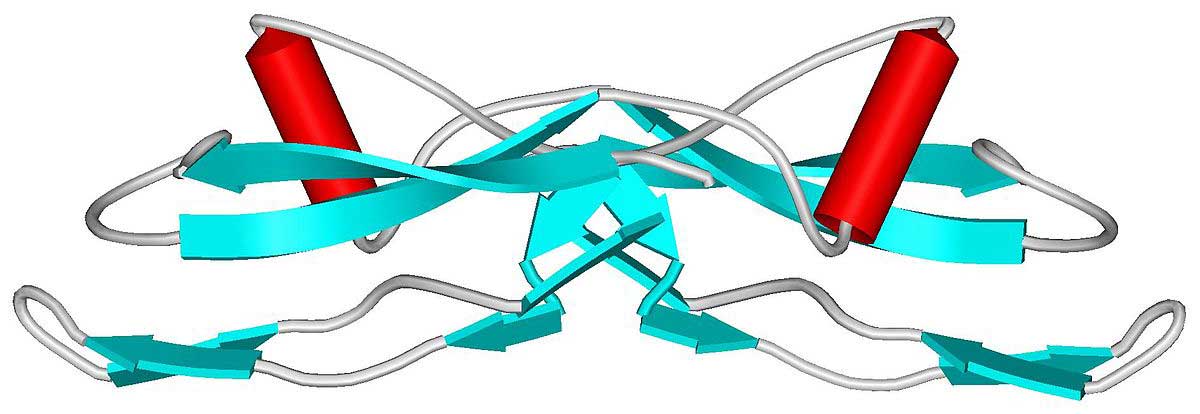

2. The clustering (or ‘aggregation’) of a protein called alpha synuclein. Specifically, they will be looking for dense circular aggregates of the protein within cells, which are referred to as Lewy bodies.

A Lewy body inside of a neuron. Source: Neuropathology-web

Alpha-synuclein is actually a very common protein in the brain – it makes up about 1% of the material in neurons (and understand that there are thousands of different proteins in a cell, thus 1% is a huge portion). For some reason, however, in Parkinson’s disease this protein starts to aggregate and ultimately forms into Lewy bodies:

A cartoon of a neuron, with the Lewy body indicated within the cell body. Source: Alzheimer’s news

In addition to Lewy bodies, the neuropathologist may also see alpha synuclein clustering in other parts of affected cells. For example, aggregated alpha synuclein can be seen in the branches of cells (these clusterings are called ‘Lewy neurites‘ – see the image below where alpha synuclein has been stained brown on a section of brain from a person with Parkinson’s disease.

Examples of Lewy neurites (indicated by arrows). Source: Wikimedia

Given these two distinctive features of the Parkinsonian brain (the loss of dopamine neurons and the aggregation of alpha synuclein), a great deal of research has focused on A.) neuroprotective agents to protect the remaining dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, and B.) compounds that stop the aggregation of alpha synuclein.

In today’s post, we will look at the research that has been conducted on one particular compounds that appears to stop the aggregation of alpha synuclein.

It is call Trehalose (pronounces ‘tray-hellos’).

Continue reading ““Three hellos” for Parkinson’s” →

Wadlow (back row on the left). Source: Telegraph

Wadlow (back row on the left). Source: Telegraph Source: Businessinsider

Source: Businessinsider