|

The contents of today’s post may not be appropriate for all readers. An illegal and potentially damaging drug is discussed. Please proceed with caution. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (or MDMA) is more commonly known as Ecstasy, ‘Molly’ or simply ‘E’. It is a controlled Class A, synthetic, psychoactive drug that was very popular with the New York and London club scene of the 1980-90s. It is chemically similar to both stimulants and hallucinogens, producing a feeling of increased energy, pleasure, emotional warmth, but also distorted sensory perception. Another curious effect of the drug: it has the ability to reduce dyskinesias – the involuntary movements associated with long-term Levodopa treatment. In today’s post, we will (try not to get ourselves into trouble by) discussing the biology of MDMA, the research that has been done on it with regards to Parkinson’s disease, and what that may tell us about dyskinesias. |

Good times. Source: Carwash

You may have heard this story before.

It is about a stuntman.

His name is Tim Lawrence, and in 1994 – at 34 years of age – he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Tim Lawrence. Source: BBC

Following the diagnosis, Tim was placed on the standard treatment for Parkinson’s disease: Levodopa. But after just a few years of taking this treatment, he began to develop dyskinesias.

Dyskinesias are involuntary movements that can develop after regular long-term use of Levodopa. There are currently few clinically approved medications for treating this debilitating side effect of Levodopa treatment. I have previously discussed dyskinesias (Click here and here for more of an explanation about them).

As his dyskinesias progressively got worse, Tim was offered and turned down deep brain stimulation as a treatment option. But by 1997, Tim says that he spent most of his waking hours with “twitching, spasmodic, involuntary, sometimes violent movements of the body’s muscles, over which the brain has absolutely no control“.

And the dyskinesias continued to get worse…

…until one night while he was out at a night club, something amazing happened:

“Standing in the club with thumping music claiming the air, I was suddenly aware that I was totally still. I felt and looked completely normal. No big deal for you, perhaps, but, for me, it was a revelation” he said.

His dyskinesias had stopped.

“I was just suddenly aware that everything was completely smooth, as though I never had the disease in the first place” he continued.

What had happened?

Tim had popped a pill of Ecstasy – about 90 minutes before his dyskinesias settled.

Ecstasy. Source: Guardian

“It didn’t occur to me that Ecstasy was involved in this novel situation. I simply enjoyed the experience and blended in with the others; dancing and feeling the music like a long-lost friend”

It didn’t take Tim long, however, to realise the connection. And not long afterwards, he spoke of his Ecstasy experience with a friend who was an ex-journalist. Probably sensing an interesting story, she suggested that they film the effect. So Tim popped a pill and they went down to a local gym where an hour later Tim started doing somersaults and back flips in front of the camera. He had changed back to being the stuntman – from being unable to move properly, to super man all in the space of an hour or so.

Tim leaping around on the gym. Source: BBC

The footage was really stunning and they decided to share it with others. The ‘others’ included some neurologists and research scientists at Hammersmith hospital in London.

Hammersmith hospital. Source: EducationfreeUSA

The scientists/clinicians who viewed the footage were probably rather sceptical about what they were watching. But who can blame them: they had never seen or heard of any drug that could make dyskinesias just disappear. Naturally their first thought was that the footage was an incredible example of the placebo effect in action. But rather than simply dismiss it as such, to their credit they decided to do two things:

- Conduct a double blind test of Tim with Ecstasy

- Have a good look at Tim’s brain while on Ecstasy

The double blind test was conducted over two days. Both sessions involved exactly the same conditions except that on one of the days Tim was given Ecstasy, and on the other he was given an identical pill that had no pharmacological effect. The researchers filmed both days and the footage was scored by independent assessors. No one involved in the test had any clue which drug Tim was taking each day. Everyone was blind.

Double blind testing of Tim. Source: BBC

The results were unambiguous though.

On day 1, Tim took the blind treatment pill and his Levodopa, and soon afterwards became dyskinetic. On day 2, Tim took the blind treatment pill and his Levodopa, and afterwards he looked perfectly normal. It was very apparent that Ecstasy was having a very strong effect on Tim and his Parkinson’s.

Next, the researchers wanted to look at Tim’s brain while he was on and off Ecstasy. They had assumed that the drug was somehow increasing the levels of dopamine in his brain…

…and this is where the whole story gets really interesting:

The Ecstasy had NO effect on dopamine levels.

The researchers found no increase in dopamine production in Tim’s brain while he was on Ecstasy. As the image below illustrates there was very little difference in the colouration of the two sides of Tim’s brain before taking Ecstasy (top row of three images) and after taking Ecstasy (bottom row of three) – indicating that the Ecstasy was having no effect on dopamine levels. If dopamine was being produced by Ecstasy treatment, the bottom row of images should all be bright red, and as you can see: they are not.

Brain scan images of dopamine in the striatum. Source: BBC

As you can probably imagine, at this point the researchers and clinicians scratching their heads, and probably wondering over their cup of tea and biscuits:

How on Earth is this man with Parkinson’s disease and severe Levodopa-induced dyskinesias suddenly able to perform acrobatic feats after taking a party drug which had no impact on dopamine production in his brain?

Enter stage left: two additional scientists. They were Professor Alan Crossman of Manchester University:

Prof Alan Crossman. Source: Linkedin

And Dr Jonathan Brotchie (now at the Krembil Research Institute, University of Toronto, Canada):

Dr Jonathan Brotchie. Source: UHN

Prof Crossman was interested in a condition called ‘Hemiballism‘, which looks very similar to dyskinesias but it is not caused by anything to do with dopamine. Rather it involves damage (usually stroke) to part of the brain called the subthalamic nucleus.

Here is a video of Hemiballism:

The subthalamic nucleus is a tiny structure in the brain that plays an important role in normal movement. It does this by regulating the activity of another structure in the brain called the globus pallidus (I have recently discussed these regions in another post about deep brain stimulation – click here to read more about this structure).

The subthalamic nucleus (in pink). Source: Neurology

Prof Crossman and colleagues had discovered the activity in the subthalamic nucleus is hyperactive (Click here for more on this). This hyperactivity increases the level of inhibitory activity in the movement parts of the brain (collectively called the basal ganglia), which leaves people with Parkinson’s disease having trouble initiating movements.

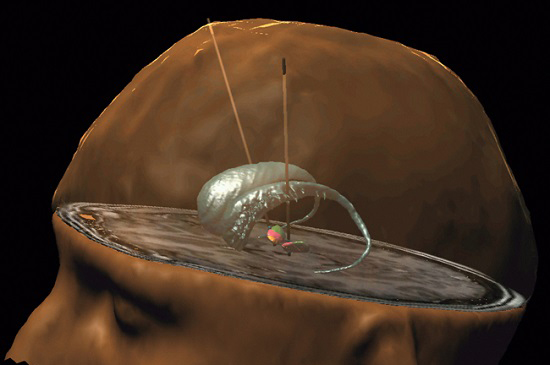

They also found that by lesioning the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinsonian primates, they could correct the motor features associated with Parkinson’s disease (Click here to read more on this). These discoveries were a major achievement, ultimately leading to the development of deep brain stimulation therapy that targeted this tiny little structure. By regulating the activity of the subthalamic nucleus, neurologists could better control the motor features of Parkinson’s disease.

Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. Source: Health-innovations

Prof Crossman, Dr Brotchie and other researchers at Hammersmith hospital in London suspected that the subthalamic nucleus was possibly the structure in the brain that was causing the amazing effect in Tim when he took Ecstasy. But if dopamine isn’t controlling the effect of Ecstasy on the subthalamic nucleus, then what is?

This is where we will leave Tim Lawrence’s story and go into the science and research of this Ecstasy phenomenon in a little more depth. For those interested, however, Tim has written about his Ecstasy experience and the journey that it has taken him on, and the quotes on this blog have been copied from that post – click here to read it.

And for those of you reading this story in utter disbelief, there is a really good BBC Horizon documentary about Tim and his amazing story. The quality of the video can be a bit poor at times, but it rolls out the whole story and also provides an intimate look at young-onset Parkinson’s (it also includes a very brief cameo from a very young Tom Issacs at 12:33 and again 13:40 minutes in):

(The video is 49 minutes long and if you do not have time to watch all of it, I recommend you skip ahead and watch for a few minutes from about 15 minutes in)

Right, let’s start getting into the science with the obvious first question:

What is Ecstasy?

For the sake of keeping everything legally above board here, I shall henceforth continue to refer to the drug in question by its research-related title MDMA.

Ok, so what is MDMA?

MDMA (or 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is a controlled Class A, synthetic, psychoactive drug. First synthesised in 1912, it was initially used to help improve psychotherapy during the 1970s, before it became popular as a street/party drug in the 1980s.

The chemical structure of MDMA. Source: Wikipedia

Approximately 30 to 60 minutes of consumption, individuals will experience euphoria, increased empathy or feelings of closeness with others, increased emotionality, mild hallucination, and enhanced or distorted sensation/perception. These effects last between 3–6 hours (varying from person to person).

MDMA is illegal in most countries and currently MDMA is not used for any medical purposes. There is, however, a phase III clinical trial for MDMA in treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder that has been agreed to by the US FDA based on the positive results of a phase II trial (Click here and here to read more on this).

How does MDMA work?

Basically, MDMA acts as a presynaptic blocking and releasing agent.

What does that mean?

At the tip of each branch stemming from a neuron there are places where the neuron will make contacts with other neurons. These spots are called synapses. When a signal is being passed between two neurons, the one sending the signal is called the presynaptic cell and the one receiving the signal is referred to as the postsynaptic cell. The signal is usually communicated between the two cells at the synapses, by the releasing of chemicals called neurotransmitters by the presynaptic cell. These neurotransmitters act on the postsynaptic cell.

The location of synapes. Source: Thatsbasicscience

Once a neurotransmitter has done its job the presynaptic cell will reabsorb the chemical so it can be re-used or recycled. This process is facilitated via specific channels called transporters. The neurotransmitter dopamine has its own transporter called the dopamine transporter.

MDMA acts in two ways:

- It blocks certain transporters (so neurotransmitters are left floating around in the synaptic space)

- It puts the transporters into reverse (that is to say, rather than helping the cell to reabsorb the neurotransmitter, MDMA encourages the transporters to release more neurotransmitters into the synapse).

As the image below illustrates, this results in more neurotransmitter (in pink) to be present in the synapse and acting on the postsynaptic cell.

Activity at the synapse. Source: NIH

MDMA affects three chemicals in the brain:

- Serotonin – which affects mood, appetite, sleep, and other functions. The release of large amounts of serotonin triggers hormones to be released that cause the emotional closeness, elevated mood, and empathy felt by those who use MDMA.

- Dopamine – causes a surge in euphoria and increased energy/activity

- Norepinephrine – increases heart rate and blood pressure, which are particularly risky for people with heart and blood vessel problems

Note: MDMA causes the release of dopamine, not an increase in the production of dopamine, which is why Tim’s brain scans did not show any increase in dopamine. This is in contrast to Levodopa which produces an actual increase in dopamine production.

What research has been done with MDMA in Parkinson’s disease?

Some time after the Tim Lawrence brought MDMA to the attention of the research community, research was begun on the effect of the drug in rodents. That work gave rise to research reports such as this one:

Title: MDMA and fenfluramine reduce L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia via indirect 5-HT1A receptor stimulation.

Authors: Bishop C, Taylor JL, Kuhn DM, Eskow KL, Park JY, Walker PD.

Journal: Eur J Neurosci. 2006 May;23(10):2669-76.

PMID: 16817869

In this study, the investigators induced Parkinson’s disease in rodents using a neurotoxin and gave them high levels of Levodopa treatment, which eventually resulted in the appearance of Levodopa-induced dyskinesias. MDMA and the serotonin releasing drug ‘Fenfluramine’ both individually reduced the levels of dyskinetic behaviour in the rats. These results suggested that MDMA was having its affect of dyskinesias via activity in the serotonin system.

What about the subthalamic nuclei? Is serotonin present in that region?

Yes it is.

Postmortem analysis of the human brain, investigating where serotonin cells project their branches to, indicates that serotonin is being released in the subthalamic nucleus. And MDMA treatment had been shown to modulate the activity of cells in the subthalamic nucleus (Click here to read more on this).

A schematic of serotonin branches in and around the human Subthalamic nucleus (STN). Source: Researchgate

After the rodent results (and similar results from other groups – click here to read more them) were published, the research community shifted its attention to see if the effect of MDMA on dyskinesias could be replicated in primates, and that effort resulted in this research report:

Title: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) inhibits dyskinesia expression and normalizes motor activity in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated primates.

Authors: Iravani MM, Jackson MJ, Kuoppamäki M, Smith LA, Jenner P.

Journal: J Neurosci. 2003 Oct 8;23(27):9107-15.

PMID: 14534244 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

This study was a follow on from the rodent research, as the researchers were seeking to determine whether the same effects would be seen in primates. First they assessed what effect MDMA would have on normal, drug-naive primates (marmosets). They found that the drug reduced motor activity, exploratory behaviour, and vocalisations.

The researchers next gave the drug to primates that had been firstly given a neurotoxin that induced Parkinson’s-like cell loss and movement problems, followed by a long-term treatment regime of Levodopa which had gradually caused dyskinesias. MDMA transiently relieved these motor problems, but the effect was short lived: after 60 minutes the movement problems returned.

Next the researchers administered MDMA and Levodopa together and they observed a marked decrease in the dyskinesias and the locomotor activity of the monkeys returned to that observed in normal animals (interestingly, they saw the same effect of MDMA in primates that had been treated with the dopamine agonist ‘pramipexole’ instead of Levodopa).

The researchers also determined that the mechanism by which MDMA appeared to be having its affect was mediated by serotonin because the effect of MDMA were completely blocked by the use of a drug called ‘Fluvoxamine’ which is a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor. This class of drug, which is used in the treatment of depression, temporally stops neurons from re-absorbing the serotonin that they have released.

How serotonin re-uptake inhibitors work. Source: Hubpages

Further supporting the role of serotonin, the investigators found that they could reduce the effectiveness of MDMA by giving the monkeys serotonin antagonists (drugs that act like serotonin). The researchers concluded that the receptors of serotonin appear to play an important role in Levodopa-induced dyskinesia, and their results may provide a framework for the use of serotonin-like drugs in the treatment of Levodopa-induced dyskinesia.

In addition, all of this research also validated Tim’s original finding and suggested that yes, MDMA was having a beneficial effect in reducing dyskinesias.

Wow! This is fantastic – MDMA stops dyskinesias! I’m going to rush out, break the law, and get me some ‘Molly’!

Mmmm yeah, before you do that, you may want to read on.

There are very good reasons why MDMA is illegal. Regular MDMA use is known to have dangerous consequences for the user, particularly those with Parkinson’s.

The damage that a user can do to themselves includes convulsions, psychosis, haemorrhaging, kidney failure, anxiety, depression, degenerated nerve branches, and cardiovascular collapse. Long-term use of MDMA can lead to:

- anxiety issues

- confusion

- depression

- disturbed sleep

- disturbing emotional reactions

- impaired memory and trouble learning

- low mood and irritability

- paranoid/delusional thoughts

- scoring significantly higher on measures of obsessive traits

But regardless all of this, use of MDMA as a treatment strategy for Levodopa-induced dyskinesias is simply not an option for one basic reason:

The drug damages the very cells that provide the beneficial effect against dyskinesias.

Long term use of MDMA results in long-lasting serotonergic dysfunction and severe (50 to 80%) reductions in levels of serotonin in the brain – Click here, here, here and here to read more about this). In the image below, you can see the branches of serotonin neurons (white lines) in the cortex of primates – the one on the left (A) in normal, the one on the right (B) has been repeated treated with MDMA for 4 days just 2 weeks previously.

Source: Thedea

Thus by using this drug to reduce dyskinesias, one would be damaging the serotonin system which would result in the drug having less and less impact on the dyskinesias over time. This is not a winning strategy.

But more importantly for people with Parkinson’s disease, MDMA also causes dysfunction in the dopamine system of the brain, potentially making a bad situation worse for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Persistent nigrostriatal dopaminergic abnormalities in ex-users of MDMA (‘Ecstasy’): an 18F-dopa PET study.

Authors: Tai YF, Hoshi R, Brignell CM, Cohen L, Brooks DJ, Curran HV, Piccini P.

Journal: Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011 Mar;36(4):735-43.

PMID: 21160467 (This is an OPEN ACCESS article if you would like to read it)

In this study, the investigators conducted brain imaging analysis on 14 ex-MDMA users and 12 drug naive control subjects. The researchers were particularly interested in the functioning of the dopamine system in these subjects. They used a special tracing element (called 18Flurodopa) that is injected into subjects and used to visualise the dopamine system. What they found in the ex-MDMA users was a hyperdopaminergic state. Dopamine turn-over was 10% higher in the ex-MDMA users when compated to normal controls and this effect was found to persist for 3 year after the individual stopped using ecstasy. Such increases have been reported in neuropsychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and psychosis.

EDITORIAL NOTE HERE: There are topics in the field of Parkinson’s research that are tough to tackle.

They involve issues concerning legality, morality and ethics. This can often give those topics an air of unassailability or of being off limits. There is, however (as Mary Baker of the Parkinson’s Disease Society rightly pointed out in the Horizon video above), a moral obligation to discuss some of these topics, especially if benefits can be attained from a better understanding of them. Thus it is important to bring them into the open for scrutiny – as the BBC Horizon show did.

There will be some readers who will think that posting all of this information regarding an illegal and damaging drug is irresponsible. They are fully entitled to that opinion. But they should know that this post has been a long time in production and the topic of many discussions around several different dinner tables, and the general sense of those discussions was that the information should be provided in a responsible manner, which I have endeavoured to do here.

I am responsible for all the information on this website, and I am sharing the backstory and research behind this topic knowing full well that some readers may foolishly consider the use of an illegal and potentially damaging drug. In my defence, I would simply say that all of the information presented in this post is already available online. I have simply tried to provide a concise version of it that makes readers aware not only of the research being carried out, but also of the terrible dangers of using the drug in question. I would also beg anyone considering the use of the drug in question not to please act on those thoughts.

Hang on a second. Why are you telling me about the dyskinesia-stopping properties of MDMA if you are only going to tell me not to use it?

Because there are some interesting developments coming down the pipe as a result of all of the MDMA-based Parkinson’s research.

Dr Jonathan Brotchie (who I mentioned above regarding his work with Prof Crossman) has been spearheading the chemical re-engineering of MDMA from a dangerous party drug to something that could be used as a medical treatment. And that work is bearing fruit:

Title:A novel MDMA analogue, UWA-101, that lacks psychoactivity and cytotoxicity, enhances L-DOPA benefit in parkinsonian primates.

Authors: Johnston TH, Millar Z, Huot P, Wagg K, Thiele S, Salomonczyk D, Yong-Kee CJ, Gandy MN, McIldowie M, Lewis KD, Gomez-Ramirez J, Lee J, Fox SH, Martin-Iverson M, Nash JE, Piggott MJ, Brotchie JM.

Journal: FASEB J. 2012 May;26(5):2154-63.

PMID: 22345403

UWA-101 (also known as α-cyclopropyl-MDMA) was a chemically engineered version of MDMA that dramatically reduced any interaction with the noradrenaline system, while retaining high affinity for the serotonin and dopamine activity of MDMA. Critically, UWA-101 lacks the toxicity of MDMA and does not cause the same MDMA behavioural effects in animals, while retaining the positive anti-Parkinsonian effects. All the good stuff, none of the bad. In fact, the researchers found that the actions of UWA-101 were even better than MDMA with regards to anti-dyskninetic effects in primate models of Parkinson’s disease, and certainly superior to any drugs currently available.

Unfortunately, at a conference in Cairns (Australia) in 2004, data from studies of UWA-101 was accidentally disclosed to the public domain, eliminating an chance of UWA-101 ever being patented. So the team went back to the lab bench and came up with a better alternative, called UWA-121.

The chemical structure of UWA-101 and UWA-121. Source: Hindawi

The researchers have subsequently published research investigating UWA-121:

Title: UWA-121, a mixed dopamine and serotonin re-uptake inhibitor, enhances L-DOPA anti-parkinsonian action without worsening dyskinesia or psychosis-like behaviours in the MPTP-lesioned common marmoset.

Authors: Huot P, Johnston TH, Lewis KD, Koprich JB, Reyes MG, Fox SH, Piggott MJ, Brotchie JM.

Journal: Neuropharmacology. 2014 Jul;82:76-87.

PMID: 24447715

By tweaking UWA-101, the researchers identified UWA-121 as a powerful alternative to the old drug. Prof Matthew Piggott (University of Western Australia) suggests that UWA-121 “improves the quality of Levodopa therapy – makes it last longer and reduces the dyskinesia (involuntary movement) that is a problem with long-term levodopa therapy” (Source). I have reached out to the researchers conducting this work, but I have had no luck in determining whether UWA-121 is heading to the clinic. The Cure Parkinson’s Trust funded some of the development of this drug, so hopefully they will be looking to take it forward for testing in the clinic. I will let you know when I hear something.

So what does it all mean?

So much of our current stock of medical drugs have an interesting backstory (take for example the case of a drug called UK92480 – a treatment for angina – that eventually became ‘viagra’ – Click here for that amusing story). In this post I have outlined the story of a chance encounter – a night out on a party drug by a man with young-onset Parkinson’s disease – that has led to an interesting tale of discovery. It is certainly my hope that some of the experimental drugs discussed in this post will eventually lead to new treatment options for people suffering from Levodopa-induced dyskinesias.

While I have asked the readers not to do anything foolish based on the information provided in this post (see editorial note above), I think that it would be equally foolish for the Parkinson’s community not to follow up this story, especially if there is the opportunity to help people deal with one of the more debilitating features of this condition. I would be interested to know what others think.

EDITORIAL NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. Please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Toghyani

well written and hopeful. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dangerous story to send out to those of us who are almost desperate for relief from Parkinsons. If you want to completely ruin your life – and whats left of your health –

quickly, go down this path.

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

Thanks for your comment. Do you think I should remove this post?

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

I find it interesting that someone.would call scientific inquiry ‘dangerous’.

LikeLike

Calling scientific inquiry ‘dangerous’ is dangerous.

LikeLike

Very interesting story and the follow-on attempt to make something that can be useful out of a ruinous ‘recreational’ drug ( I always think the term recreational gives the kids who use these things a false sense that these drugs are somehow benign so long as you do not go overboard using them). It is of particular interest when Simon explains what is happening in the brain to produce apparent outcomes that on the surface seem the same but are in fact very different – MDMA seeming to switch up Dopamine production when it does not and furthermore leading on to the ruin of neurotransmitter function. BE ADVISED: Using this substance is a shortcut to psychiatric hell and for the unluckiest death the first time they use it.

Is Simon irresponsible for giving us all this information about a banned drug? Not at all – what I learned from this article scared me more than before and for the record I am 100% against messing with the mind by using drugs. Besides, learning the way of the Buddist mind or things such as the Sedona Method can make major mood adjustments drug-free.

LikeLike

Hi Lionel,

Thanks for the comment – glad you found it interesting. A lot of soul searching was done before putting this post up (and I’m still not entirely sure it should be here). There is a lot to be said for the Buddhist approach to life.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Maybe a disclaimer or warning at the start of the post would be good. Might ruin the drama but might alert people that don’t read the whole thing? I’m not sure.

LikeLike

Hi Don – I have added a small line at the top, but I fear that it may only arouse curiosity.

Simon

LikeLike

In reply to lionelljp and Michael Barker, I personally don’t think this is posted by Simon without a very real and fearful respect, but I also don’t see he’s advocating popping ecstasy. This is important and has great potential; think of MPTP. This had been found originally in 1978; a single case post-mortem of a 23 year old student from Maryland who was the only one to try his new designer-drug. He’d intended to make MPPP, but ended up with MPTP, and that spelling mistake cost him plenty, but benefited Parkinson’s hugely as a research model that wouldn’t have to wait for cadavers.

To be honest, after being a carer for my husband for his 18 years of PD and also a writer/researcher about PD, this disease is tortuous enough without a vast life-expectancy if you started say, in your 20s. There’s no nobility in life-long, degenerative suffering.

But that’s just me bleating. I applaud Simon for this article – it expands the search towards new and less dangerous drugs…maybe a cure.

LikeLike

Hi Lisa,

Thanks for the comment. Glad you liked the post. As controversial as it is, I am pleased with the general reception of it and appreciate the positive angle everyone is taking towards it. I would very much like to see the new drugs that have evolved from the MDMA research to be tested in clinical trials. This seemed like one way of bringing them to everyone’s attention.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Simon for your informative posting. I saw the Tim Lawrence BBC Video 14+ years ago and could never understand

why I never heard much of a follow up on the ingredients of the parts of Ecstasy that brought Tim Lawrence relief all those years ago. I also cannot understand Michael Barkers Comment “If you want to completely ruin your life –” Why and how is it so????

I do not have Parkinson’s am 73 and still healthy and have never taken Ecstasy so I just can’t understand why such strong criticism on your presentation. I would like to place this on my Facebook page to let everyone know what you have studied!!!!

What am I missing here and am I still a naive 73 year old living in Dodo land??????

LikeLike

Hi Bruno,

Thanks for your comment – glad you liked the post. It is a really interesting story, one that I am still following up.

I suspect that there is a general and understandable concern that people who are desperate to ride themselves of dyskinesias will try just about anything, even if it is an illegal, potentially damaging drug. But my reasons for posting the story were more focused on bringing attention to the research that has stemmed from Tim’s initial finding. I am disappointed that the new drugs that have been developed from this story are not being taken to the clinic.

Please feel free to share or do whatever you like with anything you find on the website. It is all licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, so you can do whatever you like with it.

Oh, and I’m 22 forever!

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon have you had a chance to look at Medical Cannabis and Parkinson???? Good anecdotal evidence that something is happening there also. ????

LikeLike

Hi Bruno,

I had a post on Cannabis and Parkinson’s last year (https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2016/09/25/cannabis/) – curiously one of the more popular posts! Anecdotally there is a lot of material, but in clinical studies the picture is a lot more vague. Parkinson’s UK recently posted about it as well and they came to a similar conclusion (https://medium.com/parkinsons-uk/the-case-for-and-against-cannabis-6c6dbd232ac5).

Fair to say that the jury is out. It would appear to have an effect for a subset of the PD community (I’m guessing maybe 20-30% of folks), but this is just me guess-timating based on the anecdotal stuff.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

“I am disappointed that the new drugs that have been developed from this story are not being taken to the clinic.”

Simon any reason for this. I find it hard to believe that treatments that show great promise are not tested in the market place or clinic as you say ??? Again curious because that Video I saw all those years ago is still firmly stuck in my mind of what a great break through this could be for those people having to suffer this tragic disease !!!!

LikeLike

Hi Bruno,

UWA-121 has been publicly disclosed which mean it can’t be patented. Without a patent, very few drug companies will touch it. I have a hard time with this idea, because while everyone is hell-bent on finding ‘a cure’ I think there is still an urgent need for the continued development of symptomatic treatments for PD (particularly in the case of dyskinesias). I am following up this story, hoping for a happier ending. Thanks for your comment.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Does anyone know how Tim Lawrence is doing today? Is he involved in the Parkinson’s community. I would like to reach out to him.

LikeLike

Honestly getting relief even if it leads to long term detrimental effects could still be worth it for some people. Everybody’s got something that we probably shouldn’t do so much, be it alcohol, smoking, overeating, extreme sports… The reason? We’ll die one day anyway. Parkinson’s sucks, so why not find relief once in a while?

LikeLike