|

One of the cardinal features of the Parkinsonian brain are dense, circular clusters of protein that we call ‘Lewy bodies’. But what exactly are these Lewy bodies? How do they form? And what function do they serve? More importantly: Are they part of the problem – helping to cause of Parkinson’s? Or are they a desperate attempt by a sick cell to save itself? In today’s post, we will have a look at new research that makes a very close inspection of Lewy bodies and finds some interesting new details that might tell us something about Parkinson’s. |

Neuropathologists conducting a gross examination of a brain. Source: NBC

A definitive diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease can only be made at the postmortem stage with an examination of the brain. Until that moment, all cases of Parkinson’s disease are ‘suspected’.

When a neuropathologist makes an examination of the brain of a person who passed away with the clinical features of Parkinson’s, there are two characteristic hallmarks that they will be looking for in order to provide a final diagnosis of the condition:

1. The loss of specific populations of cells in the brain, such as the dopamine producing neurons in a region called the substantia nigra, which lies in an area called the midbrain (at the base of the brain/top of the brain stem).

The dark pigmented dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra are reduced in the Parkinson’s disease brain (right). Source:Memorangapp

2. Dense, circular clusters (or aggregates) of protein within cells, which are called Lewy bodies.

A cartoon of a neuron, with the Lewy body indicated within the cell body. Source: Alzheimer’s news

What is a Lewy body?

A Lewy body is referred to as a cellular inclusion (that is, ‘a thing that is included within a whole’), as they are almost always found inside the cell body. They generally measure between 5–25 microns in diameter (5 microns is 0.005 mm) thus they are tiny, but when compared to the neuron within which they reside they are rather large (neurons usually measures 40-100 microns in diameter).

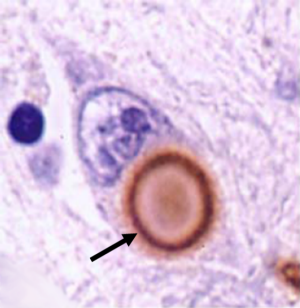

A photo of a Lewy body inside of a neuron. Source: Neuropathology-web

How do Lewy bodies form? And what is their function?

The short answer to these questions is:

Source: Wellbeing365

The longer answer is: Our understanding of how Lewy bodies are formed – and their actual role in neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s – is extremely limited. No one has ever observed one forming. Lewy bodies are very difficult to generate in the lab under experimental conditions. And as for their function, this is the source of much guess work and serious debate (we’ll come back to this topic later in this post).

Ok, but what are Lewy bodies actually made of?

Most websites describing with Parkinson’s disease will tell you that Lewy bodies are made up of a protein called alpha synuclein, and this is partly true.

Over the years quite a few researcher have had a close look at the contents of Lewy bodies, including the man after whom they are named.

In 1912, just two years out of medical school and in his first year as Director of the Neuropsychiatric Laboratory at the University of Breslau Medical School, neuropathologist Friedrich Lewy published his findings from analysing postmortem sections of brain from people who passed away with Parkinson’s.

Friedrich Lewy. Source: Lewy Body Society

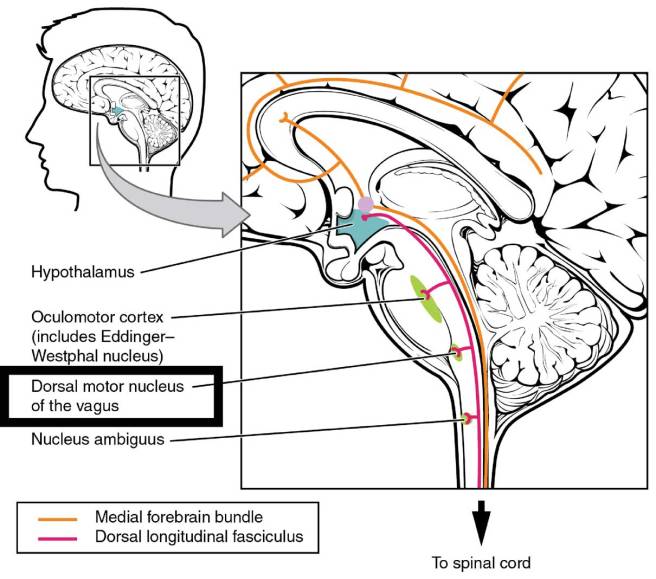

Based on the examination of 25 patients with Parkinson’s, Lewy had observed disease-specific features in a region of the brain called the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve (he didn’t look at the substantia nigra). The dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve is a collection of cells that resides in the brain stem (at the base of the brain) and it receives signals from the heart, lungs and stomach.

Source: oerpub.github

Lewy reported that a ‘large number‘ of the samples from patients with Parkinson’s who showed ‘tremor and tension of their vocal cords‘, displayed small, dense circular objects inside the cells of the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve. He had not found any of these same features in six cases of ‘severely senile or arteriosclerotic‘ patients.

These objects were later called “Lewy bodies” (named by Konstantin Tretiakoff in 1919 – Source).

A lewy body (stained brown, indicated with a black arrow) inside a cell. Source: Cure Dementia

As I have previously mentioned (Click here to read that post), in 1931, Friedrich Lewy presented his research at the International Congress of Neurology in Bern. During that talk he noted the similarities between the circular inclusions (called ‘Negri bodies’) in the brains of people who suffered from rabies and his own Lewy bodies.

A Negri body in a cell affected by rabies (arrow). Source: Nethealthbook

Given the similarities, Lewy proposed a viral cause for Parkinson’s disease. Whether viruses play a role in the development of Parkinson’s is yet to be determined, but Lewy’s initial conclusion was based on the microscopy technology that he had available to him at the time of his research.

Since then there has been a wee bit of progress in our ability to look at the microscopic world. For example, back in 2009 the technology company IBM took these images of pentacene molecules:

Source: Singularityhub

The minute scale of this image is STUNNING. Understand that the scale bar in the bottom left-hand corner of both images is provided in Angstroms. An angstroms is 10−10 m (that is one ten-billionth of a metre or 0.1 nanometre).

How wide is a nanometre?

Not very. A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick. So the molecules in the images above are very, very, very,….(insert lots of verys here)….very small.

And using these advances in microscopy technology, we have been able to have a closer look at Lewy bodies. The first indepth analyses came in the 1960’s when electron microscopes were first pointed at sections of brain tissue from Parkinsonian brains. This resulted in research reports such as:

Title: Phase and Electron Microscopic Observations of Lewy Bodies and Melanin Granules in the Substantia Nigra and Locus Caeruleus in Parkinson’s Disease

Authors: Duffy PE & Tennyson VM

Journal: Journal of Neuropathology Experimental Neurology, 24 (3) 1 July 1965, 398–414

PMID: N/A

In this first high magnification study, the researchers described Lewy bodies as a circular bodies with densely packed centre (or core), surrounded by radiating fibres (or filaments). There was no obvious confining membrane. This first description has been confirmed by numerous follow up studies, and has long remained the primary description of the structure of Lewy bodies.

In the image below, you can see the densely packed core of a Lewy body (labelled with a small white ‘C’) and the radiating filaments in the ‘helo’ around the periphry (labelled with a hard to see white ‘H’ on the left of centre of the image):

A very high magnification image of a Lewy body. Source: Lancet

And these initial observations were quickly replicated and extended by other research groups at the time:

Title: Ultrastructural observations in Parkinsonism.

Authors: Roy S, Wolman L.

Journal: J Pathol. 1969 Sep;99(1):39-44.

PMID: 5359222

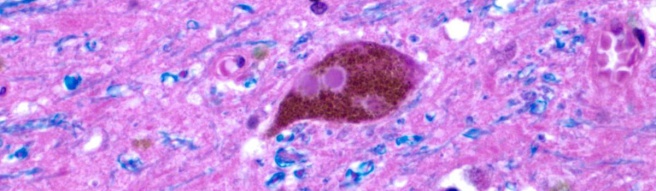

In this study, when the researchers had a close look at Lewy bodies in sections of brain from people with Parkinson’s, they proposed two different types of Lewy body:

- A more common variety (similar to what Duffy & Tennyson had previously described), composed of granular material in the core of the Lewy body, while thread-like fibers (called fibrils) radiate around the periphery. This is considered a ‘classical’ type of Lewy body.

- The second type of Lewy body was composed almost entirely of circular fibrils. This feature gave this kind of Lewy body the appearance of a uniform density. This is considered a ‘cortical’ type of Lewy body, as these are mainly found in cortical regions of the brain.

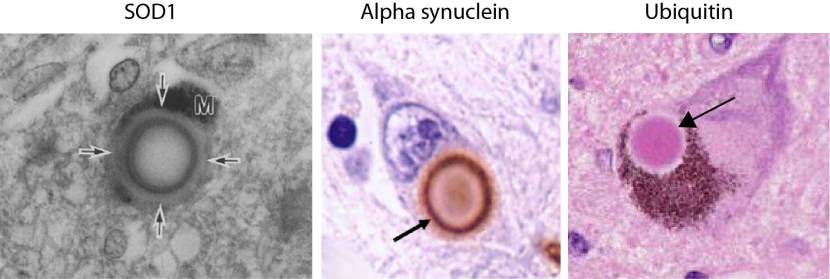

More recently, researchers have been able to stain Lewy bodies using reagents for particular proteins and this have provided evidence of specific localisation of those proteins. For example, Parkinson’s associated proteins like alpha synuclein and SOD1 appear to be present in the periphery of the Lewy body, as opposed to another Parkinson’s associated protein, Ubiquitin, which is mainly present in the core of Lewy bodies (see image below).

And using different staining techniques at least 90 different molecules have been found in Lewy bodies, so it is wrong to think of them as simply aggregates of alpha synuclein (Source).

Until recently, however, a combination of all of the various microscopic techniques had not been conducted, and this brings us to the research report that this post is going to review.

EDITOR’S NOTE: I AM BREAKING ALL THE RULES TODAY BY REVIEWING THE RESULTS OF A RESEARCH MANUSCRIPT THAT HAS NOT YET BEEN THROUGH THE PEER-REVIEW PROCESS. THE RESEARCH REPORT IN QUESTION HAS BEEN SITTING ON THE PRE-PRINT WEBSITE BIORXIV (WHICH WE DISCUSSED IN A PREVIOUS POST – CLICK HERE TO READ THAT POST) SINCE JULY AND I AM TOO IMPATIENT TO WAIT FOR THE PEER-REVIEW PROCESS TO RUN ITS COURSE. THIS IS BREAKING THE RULES SLIGHTLY, BUT WHEN THE FINAL VERSION OF THIS REPORT IS PUBLISHED I WILL ADAPT THIS POST ACCORDING TO ANY CHANGES THAT MAY HAVE OCCURRED.

Recently this research report was posted on the preprint website BioRxiv:

Title: Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of a crowded organellar membranous medley

Authors: Shahmoradian SH, Genoud C, Graff-Meyer A, Hench J, Moors T, Schweighauser G, Wang J, Goldie KN, Sütterlin R, Castaño-Díez D, Pérez-Navarro P, Huisman E, Ipsen S, Ingrassia A, de Gier Y, Rozemuller AJM, De Paepe A, Erny J, Staempfli A, Hoernschemeyer J, Großerüschkamp F, Niedieker D, El-Mashtoly SF, Quadri M, van IJcken WFJ, Bonifati V, Gerwert K, Bohrmann B, Frank S, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, van de Berg WDJ, Lauer ME

Journal: bioRxiv preprint first posted online May. 16, 2017

PMID: N/A (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers took sections of postmortem substantia nigra (the region of the brain where the dopamine neurons reside (see the top of this post) and hippocampus – a region of the brain involved in memory formation – and examined them using a range of complementary methods in order to study Lewy bodies at the nanometer scale. Before beginning, the investigators checked to see if the individuals – from whom the samples had been collected – had any known Parkinson’s-associated genetic variants. They found none and so these specimens were coming from what can be considered spontaneous (or idiopathic) Parkinson’s.

What they found was fascinating.

Using multiple microscopic imaging techniques, the investigators discovered that the interior of Lewy bodies is actually a crowded mess of membranes from vesicles (the bags in which proteins are transported around cells – the aqua blue arrows in the image below), old & deformed mitochondria (the power stations of the cells – the orange arrows in the image below) and disrupted structural elements of the cells (various proteins). This was in complete contrast to the expected filaments.

High magnification image of a Lewy body. Source: Biorxiv

The deformed mitochondria were found to be present around the periphery of the Lewy body, while the vesicles were largely present in the middle of the inclusions. And this finding was also in opposition to previous research which found vesicles crowded around the edge of Lewy bodies:

Title: Dense core vesicles around the Lewy body in incidental Parkinson’s disease: an electron microscopic study

Authors: Watanabe I, Vachal E, Tomita T.

Journal: Acta Neuropathol. 1977 Aug 16;39(2):173-5.

PMID: 197775

In this study, the researchers described an individual postmortem case of Lewy body disease in which numerous dense circular bags (called vesicles) were found to be particularly numerous in the vicinity of the Lewy bodies in cells in the locus coeruleus – an area of the brain stem that is affected by Parkinson’s. They actually speculated on whether this phenomenon could be occurring at the early stage of Lewy body production – which may explain the differences observed between studies (NOTE: these studies are based on a small number of brains being analysed, and these brains could be at different stage of their respective conditions).

But the results of this new ‘un-published’ bioRxiv research report point towards possible origins of Lewy bodies. And given the results of their study, the researchers have proposed a five step model of how Lewy bodies may be forming (see the image below):

Step A: Organelles within a cell are performing their normal functions and all is well. An organelle is any tiny cellular structure that performs specific functions within a cell, including mitochondria.

Step B: Somehow there is the introduction of aggregated or toxic alpha synuclein, along with other proteins that have a tendency to cluster and aggregate. And these introduced proteins start to mingle with all of the organelles.

Step C: These introduced, trouble making proteins next begin to disrupt the membranes of some of the organelles, causing them to spill open and debris start to pile up in the immediate vicinity.

Step D: The debris from the disrupted and fragmented membranes of organelles accelerates the aggregation.

Step E: Larger clumps of these membrane fragments, aggregated proteins, and vesicles begin to compact over time in the extremely restricted space of the cell, and this gives rise to the basic structure of Lewy bodies.

A model of Lewy body formation. Source: Biorxiv

The investigators concluded that their findings point toward impaired trafficking of organelles as a key driver of the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Ok. So that’s Parkinson’s all sorted out then?

Yeeeeah, no.

Unfortunately not.

While the results of this new study are extremely interesting, there is still something critical missing from the picture. You see, when we inject cells with high levels of toxic alpha synuclein and other ‘sticky’ proteins, they don’t form Lewy bodies. And when we replicate those experiments in mice, they don’t form Lewy bodies.

So what mystery component is missing that we can’t experimentally produce a Lewy body? (Answer that question and I’ll give you a Nobel prize).

It’s an interesting study, but why has it not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal?

Who knows.

Welcome to the world of academic research. Publication of data can easily take 6-12 months of back-and-forth between researchers and anonymous reviewers. It is unfortunately a slow process.

Source: PhDcomics

And to give you an idea of how slow the current process of publishing research is: this unpublished manuscript that we have discussed here today, has already been cited by two recently published articles.

How crazy is that?!?

But are Lewy bodies dangerous?

This is the big unanswered question.

Initially there were a number of research reports that looked at the number of Lewy bodies in postmortem brains of people who passed away with Parkinson’s. Those studies indicated that the number of Lewy bodies in patients with mild to moderate cell loss in the substantia nigra was higher than in patients with severe neuronal depletion. This observation has led to the assumption that Lewy body-containing neurons are dying cells, and that Lewy bodies were obviously dangerous.

But this idea has subsequently been challenged.

And that challenge probably started with this report:

Title: Contribution of somal Lewy bodies to neuronal death

Authors: Tompkins MM, Hill WD

Journal: Brain Res. 1997 Nov 14;775(1-2):24-9

PMID: 9439824

In this study, the researchers wanted to determine if signs of cell death were more common in dopamine neurons that contained Lewy bodies than dopamine neurons without Lewy bodies. They had previously perfected a staining protocol that allowed them to identify cells in the early stages of apoptosis (or programmed cell death), and they now wanted to use that protocol to assess the role of Lewy bodies.

They stained sections of brain from four postmortem cases (2 cases of Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s and 2 cases of Dementia with Lewy bodies). Over 1200 neurons were assessed per brain, and what the investigators found was that the total number of neurons that were displaying signs of apoptosis was much greater in the dopamine neurons without Lewy bodies.

That is to say, the majority of dopamine neurons undergoing apoptotic cell death did not appear to contain Lewy bodies (in fact, one of the cases had NO Lewy body-containing dopamine neurons undergoing apoptotic cell death – Lewy bodies were present in the specimen, but there was no sign of cell death in those Lewy bodies-containing cells). This finding led the researchers to conclude that some dopamine cells may be dying before Lewy bodies have a chance to form, which would suggest that the presence of a Lewy bodies does not predispose a neuron to cell death.

And this result was replicated by another independent research group:

Title: Lewy pathology is not the first sign of degeneration in vulnerable neurons in Parkinson disease.

Authors: Milber JM, Noorigian JV, Morley JF, Petrovitch H, White L, Ross GW, Duda JE.

Journal: Neurology. 2012 Dec 11;79(24):2307-14.

PMID: 23152586 (This article is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

The researchers who conducted this study examined the extent of dopamine neuron dysfunction and degeneration among postmortem sections of brain from 17 healthy controls, 33 with incidental Lewy body disease (ILBD), and 13 cases of Parkinson’s (with a mean disease duration of 8.3 years). While the density of dopamine neurons (as measured by their total number) was observed to decrease as the Lewy body burden became more severe, a significantly high percentage of dopamine cells were found to be dysfunctional or dying without any Lewy bodies present inside those cells. These results suggest that significant neurodegeneration and cellular dysfunction precede the appearance of Lewy bodies in dopamine neurons,… which basically challenges the idea that Lewy bodies are playing a pathogenic role of Parkinson’s.

And this phenomenon of cell death occurring before protein aggregation does not appear to be specific to Parkinson’s – similar results have been observed in Huntington’s disease (Click here to read more about this).

For a good OPEN ACCESS review of Lewy bodies – click here.

So Lewy bodies aren’t involved with Parkinson’s?

I’m not saying that.

But it is strange that some people with “Parkinson’s” don’t have Lewy bodies in their brains (Click here to read more about this), and then there are the 20% to 50% of cases of pathologically proven Alzheimer’s disease that also have Lewy bodies (Click here to read more about this).

On top of that, there was the study which involved the analysis of 273 brains from people who died from conditions other than Parkinson’s disease. The research found that the presence of Lewy bodies in the brain increased from 3.8% to 12.8% between the sixth and ninth decades – and remember these brains were not clinically associated with Parkinson’s (Click here to read about that research).

Another study found that 33 of 139 brains from ‘clinically normal’ individuals contained Lewy bodies in various regions (Click here to read that study).

But maybe those people were going to develop Parkinson’s later in life?

Perhaps. But something smells a bit fishy to me.

And based on the evidence presented here today, your honour, I am officially asking if Lewy bodies are fake news.

What does it all mean?

A research scientist’s job is to basically question everything.

Particularly anything that is considered ‘dogma’. You are given a spade as you enter the world of scientific research and encouraged to dig until you find something (and to keep up all of the digging until you are put out to pasture). Now, if you are luck enough to actually find something interesting during your dig, others will swarm to your hole and help you dig (whether you like it or not). And the bigger the find, the bigger the ultimate hole.

Sometimes during that digging process, however, certain discoveries will be made that may question whether the initial finding, forcing the diggers to ask was the finding as big as initially thought. The collective consensus of all the diggers now in your hole will determine whether you keep on digging or not. But in many situations the decision to keep digging will simply come down to the fact that this particular hole is the best lead we have to understanding a particular topic or medical condition. And so let’s just keep digging.

For over 100 years now, researchers have been fascinated with cellular inclusions called Lewy bodies. And during that period of time, Lewy bodies have become what is considered one of the cardinal features of the Parkinsonian brain, and implicated as a potentially instrumental agent in the course of the condition… despite the occasional bit of research that has questioned their true relevance to Parkinson’s.

New evidence from a yet-to-be peer-reviewed research article provides not only an intimate view of the composition of Lewy bodies – suggesting that these cellular inclusions are the result of accumulating piles of cellular debris – but also proposes a model of how Lewy bodies may be developing and drive the neurodegenerative condition. Whether these aggregates are actually involved in the course of Parkinson’s – or simply caught in the wrong place at the wrong time – is yet to be fully determined.

I may have presented a slightly biased view of Lewy bodies in this post, one that has gone against the general consensus.

But then again I like to think of myself as a research scientist. And while I’m digging, I’ll question everything.

Poor little Mr “Lewy body” got the blame simply due to his presence. Source: Youtube

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Washington.edu

… the plot thickens.

Vewy interesting!

LikeLike

Again a very interesting way of explaining hard science.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Keep on questioning everything, Simon. Ignoring the */received wisdom /*is the right way to proceed [as long as it does not slow down the research for a cure too much]. Keith

LikeLike

1. I like how you put “Parkinson” in quotation marks. Indeed we might be dealing with the multitude of various cellular malfunctions that lead to clinical manifestations we call Parkinson disease.

2. So if I understood it right Lewy bodies are not observed in ANY animal models, not even primates? That in itself is very interesting and puzzling.

3. I wonder if similar microscopic research was done on the rabies infected brain cell structures originally observed by Mr. Lewy himself.

LikeLike

Hi Felix,

Thanks for the interesting list of comments/questions.

1. One only needs to go along to a Parkinson’s support group meeting to see that there is tremendous variability between individual sufferers. The curious aspect of the multitude combinations of cellular malfunctions leading to similar clinical manifestations is that they are actually rather similar. Why don’t they results in completely different manifestations. Perhaps our measures are not sharp enough to pick up the wider differences. And then there may also be some weird common features between individuals with PD (such as their change in bodily smell – https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2015/10/23/the-smell-of-parkinsons-disease/).

2. So I have been contacted by a few researchers questioning my statement that “Lewy bodies are very difficult to generate in the lab under experimental conditions”

There have been research reports suggesting eosine-stained cellular inclusions in mice and aged Parkinsonian squirrel monkey (chronically treated with the neurotoxin MPTP – see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15716361 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3024555 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8380528).

There have also been reports of increased levels of alpha synuclein protein in the substantia nigra of primates treated with MPTP for long periods (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10683860).

And when you introduce high levels of alpha-synuclein fibrils to cell in culture or in vivo, we can also see intracellular inclusions that very closely resemble Lewy bodies

(see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4263445/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4640952/). The big question is, however, are they actually Lewy bodies? I’m not really convinced, but that’s just me.

3. Negri bodies (from cases of rabies) are viral factories. Using high magnification imaging has confirmed this. They look very different to Lewy bodies when you get up close and personal. Here is an interesting link about negri bodies – http://www.virology.ws/2009/04/01/negri-bodies-and-rabies/

Thanks again for the questions.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon, Could you please comment on the reported significant reduction in incidents of Parkinson disease in those who had vagotomy (removal of the vagus nerve mentioned in this post)? Thanks, Felix

LikeLike

Hi Felix,

Thanks for the interesting question. We have looked at the gut connection several times. In fact, this research was the very first topic discussed here on the SoPD (https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2015/09/09/september-7-13th-2015/).

I have subsequently added other posts (such as https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2016/07/06/a-gut-feeling-about-gut-feelings/ – and most recently – https://scienceofparkinsons.com/2017/05/03/trying-to-digest-gut-research/) as reports have come to hand. While there was initially a lot of excitement about this gut-brain connection, I think it is fair to say that that excitement has been subsequently tempered and a lot of folks are waiting for new data to provide more convincing evidence (that is just my opinion). It will be interesting to see what research comes next on this topic.

Kind regards,

Simon

LikeLike

Simon, I find this riveting though I wish I understood the implications better. In what way might this lewy body challenge be related to newly discovered species of ASN called “P-alpha-syn-star” or Pα-syn?

LikeLike

Awesome commentary!!! Perhaps Lewy bodies are a result and not a cause. Do they eventually completely take over the cell that they reside in?

LikeLike