|

# # # # This week the outcome of an ongoing Parkinson’s clinical trial was announced. Data collected during Part 1 of the ongoing Phase 2 PASADENA alpha synuclein immunotherapy study for Parkinson’s apparently suggests that the treatment – called prasinezumab – has not achieved it’s primary endpoint (the pre-determined measure of whether the agent has an effect in slowing Parkinson’s progression – in this case the UPDRS clinical rating scale). But, intriguingly, the announcement did suggest ‘signals of efficacy‘ in secondary and exploratory measures. In today’s post, we will discuss what immunotherapy is, what we know about the PASADENA study, and why no one should be over reacting to this announcement. # # # # |

At 7am on Wednesday, April 22nd, 2020, the pharmaceutical company Roche published its sales results for the 1st Quarter. This was just prior to the opening of the Swiss Stock Exchange. The financial report looked very good, particularly considering the current COVID-19 economic climate.

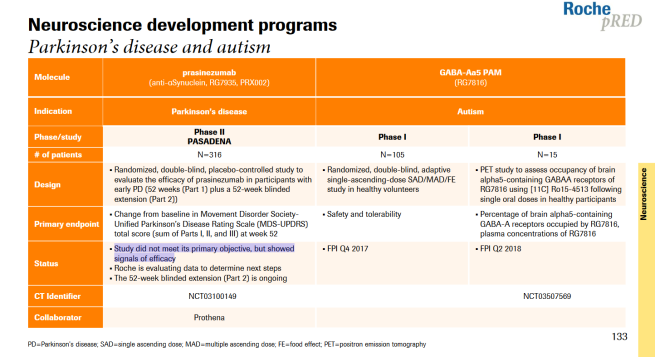

There was, however, one sentence on page 133 of the results that grabbed some attention:

Source: Roche

Source: Roche

For those of you (like myself) who struggle with fine print, the sentence reads:

“Study did not meet its primary objective, but showed signals of efficacy“

This was how the pharmaceutical giant announced the top line result of the ongoing Phase II PASADENA study evaluating the immunotherapy treatment prasinezumab in recently diagnosed individuals with Parkinson’s (listed on the Clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03100149).

At the time of publishing this SoPD post, Roche are yet to provide any further information (press release, announcement, memo, tweet, etc) regarding the results of the study.

Thankfully, a smaller biotech firm called Prothena – which is also involved in the development of the agent being tested in the Pasadena study – has kindly provided a few more details regarding these results.

I usually don’t like discussing clinical trial results on the SoPD until the final report is published, but in this circumstance I will make an exception.

I usually don’t like discussing clinical trial results on the SoPD until the final report is published, but in this circumstance I will make an exception.

In today’s post we will discuss what details have been shared in the Prothena press release regarding the Prasinezumab clinical trial in Parkinson’s (Click here to read the press release).

What is Prasinezumab?

Prasinezumab is an experimental immunotherapy approach for Parkinson’s.

What is immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy is a method of boosting the body’s immune system to better fight a particular disease.

It involves utilising the immune system of your body, and artificially altering it to target a particular protein/disease-causing agent that is not usually recognised as a pathogen (a disease causing agent).

Immune cells attacking a cancer cell. Source: Lindau-nobel

Immune cells attacking a cancer cell. Source: Lindau-nobel

It is potentially a very powerful method of treating a wide range of medical conditions, and the research on immunotherapy is particularly robust in the field of oncology (‘cancer’). Numerous methods of immunotherapy have been developed for cancer and are currently being tested in the clinic (Click here to read about the many clinical trials now under way).

Many approaches to immunotherapy against cancer. Source: Bloomberg

Many approaches to immunotherapy against cancer. Source: Bloomberg

One of the most promising of these cancer-based immunotherapy approaches is called CART immunotherapy (or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy).

This video explains how CART immunotherapy works:

CART cell technology is being developed for Parkinson’s, but that is a topic for another SoPD post. Stay tuned.

Interesting, but how is immunotherapy being used against Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s is a slow and progressive disease.

And one of the mysteries about the condition is why this is the case? Why is there a slow, gradual progression to the neurodegeneration associated with Parkinson’s?

For example, when an individual suffers a stroke, there is an initial insult which causes damage and affects well being. Over time, the situation stablises, and (depending of circumstances) some individuals can regain certain aspects of the lost function as their brain adapts to the new reality – there can be some evidence of neuroregenerative processes.

The time course of a stroke. Source: Smw

The time course of a stroke. Source: Smw

But in the case of neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s, the damage and loss of function is slow and progressive.

And this raises the obvious question: Why?

Why does the loss of cells continue?

And why at such a slow pace?

Do we know?

We do not.

But one of the big theories about how Parkinson’s progresses involves the idea that a toxic form of the Parkinson’s-associated protein, alpha synuclein. The idea is that this toxic form of the protein could be being passed from cell to cell.

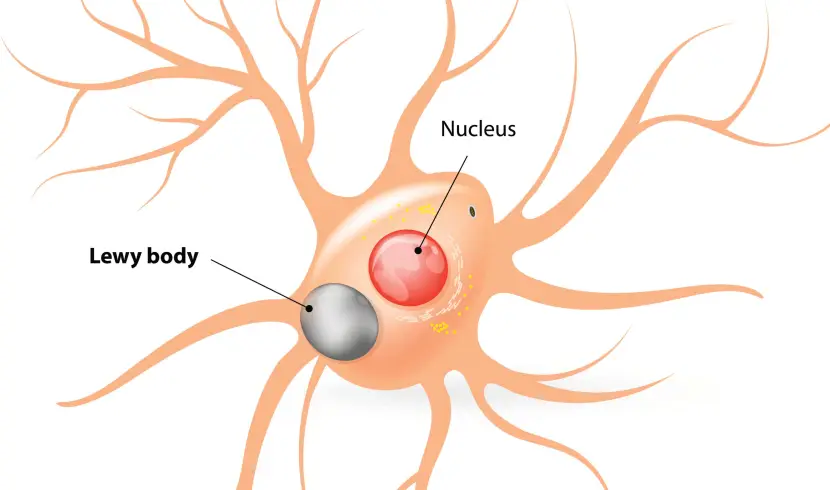

And as this toxic version of alpha synuclein is absorbed by each naive, healthy cell, it starts causing trouble in that cell and this results in the clustering (or aggregation) of protein, which is believed to lead to the appearance of Lewy bodies in those previously healthy cells.

Lewy bodies are dense circular clusters of alpha synuclein protein (and other proteins) that are found in specific regions of the brain in people with Parkinson’s (Click here for more on Lewy bodies).

A cartoon of a neuron, with the Lewy body indicated within the cell body. Source: Alzheimer’s news

A cartoon of a neuron, with the Lewy body indicated within the cell body. Source: Alzheimer’s news

The aggregated alpha synuclein protein, however, is not limited to just the Lewy bodies. In the affected areas of the Parkinsonian brain, aggregated alpha synuclein can be seen in the branches (or neurites; see black arrow in the image below) of cells – see the image below where alpha synuclein has been stained brown on a section of brain from a person with Parkinson’s.

Examples of Lewy neurites (stained in brown; indicated by arrows). Source: Wikimedia

How does alpha synuclein protein become toxic?

When alpha synuclein protein is produced by a cell, it normally referred as a ‘natively unfolded protein’, in that is does not really have a defined structure. Alone, it will look like this:

Alpha synuclein. Source: Wikipedia

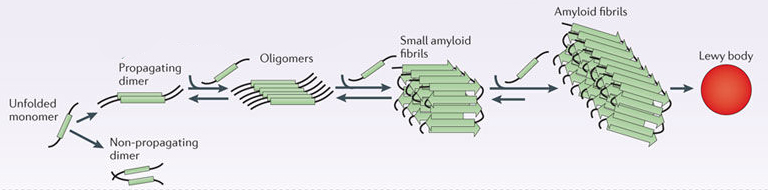

By itself, alpha synuclein is considered a monomer, or a single molecule that can bind to other molecules. When it does bind to other alpha synuclein proteins, they form an oligomer (a collection of a certain number of monomers in a specific structure). In Parkinson’s, alpha synuclein also binds (or aggregates) to form what are called ‘fibrils’.

Microscopic images of Monomers, oligomers and fibrils. Source: Brain

And it is believed that the oligomer and fibril forms of alpha synuclein protein give rise to the aggregations of protein that we refer to as Lewy bodies:

Parkinson’s associated alpha synuclein. Source: Nature

And it also believed that the oligomer and fibril forms of alpha synuclein protein may be being passed from cell to cell, and ‘seeding’ protein aggregation in new cells. And this is how the condition may be slowly progressing.

Is there any evidence of this transfer of the alpha synuclein protein?

So back in the 1990s, there were a series of clinical trials of cell transplantation conducted on people with Parkinson’s. The idea was to replace the cells that have been lost to the condition (Click here to read a previous post about cell transplantation). Many of the individuals who were transplanted in that study have now passed away (by natural causes) and their brains have been examined post-mortem.

One very interesting finding from the analysis of those brains is that some of the cells in the transplants have Lewy bodies in them (up to 10% of transplanted cells in one case – Click here to read the research report on that case).

Above are photos of neurons from the post-mortem brains of people with Parkinson’s that received transplants. White arrows in the images above indicate lewy bodies inside transplanted cells. Source: The Lancet

Above are photos of neurons from the post-mortem brains of people with Parkinson’s that received transplants. White arrows in the images above indicate lewy bodies inside transplanted cells. Source: The Lancet

This finding suggested to researchers that somehow this neurodegenerative condition is being passed from the Parkinson’s affected brain to the healthy, young transplanted cells.

And researchers have proposed that the toxic form of the Parkinson’s-associated protein alpha synuclein may be the guilty party in this process (Click here to read more on this idea).

|

# RECAP #1: Parkinson’s is a slow, progressive condition. Researchers have long questioned why there is progression. Several theories propose that a toxic form of the protein alpha synuclein may be passed from cell to cell and this is how the condition is progressing in the brain, which gradually results in the neurodegeneration and clinical symptoms that are observed. # |

So how is immunotherapy being applied to Parkinson’s?

One way of dealing with this problem of cell-to-cell transfer of the toxic form of alpha synuclein is to grab the protein as it is being passed between the cells, and then remove it from the body.

This idea has given rise to a series of ongoing clinical trials that are using antibodies which target the toxic form of the alpha synuclein protein.

What are antibodies?

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that the immune system naturally and continuously produces to identify anything in the body that is ‘not self’ (that is, not a normally occurring part of you – think of viruses, bacteria, etc).

Monoclonal antibodies. Source: Astrazeneca

Antibodies act like alert flags for the immune system. When antibodies bind to something, they alert the immune system to investigate and potentially remove. Each antibody targets a very specific structure, while ignoring everything else.

In this fashion, antibodies are a very powerful method of removing items from the body that are causing trouble or not wanted.

And researchers have adapted this natural system for Parkinson’s using immunotherapy approaches. Currently, immunotherapy is being tested in Parkinson’s in two ways:

- Active immunisation – this approach involves the body’s immune system being encouraged to target the toxic form of alpha synuclein. The best example of this is a vaccine – a tiny fragment of the troublesome pathogen is injected into the body before the body is attacked, which helps to build up the immune systems resistance to the pathogen (thus preventing the disease from occurring).

- Passive immunisation – this approach involves researchers designing antibodies themselves that specifically target a pathogen (such as the toxic form of alpha synuclein, while leaving the normal version of the protein alone). These artificially generated antibodies can then be injected into the body.

Immunotherapy. Source: Acimmune

Several biotech companies are currently clinically testing immunotherapy approaches for Parkinson’s. An Austrian company called AFFiRiS is trialing an active immunisation method with their “Parkinson’s vaccine” called ‘AFFITOPE® PD01A’ (Click here to read a previous post on this topic). They are planning to start Phase II clinical trials later this year (Click here to read more about this).

The big pharmaceutical company Biogen is also testing an immunotherapy treatment for Parkinson’s, but unlike the AFFiRiS active immunisation method, the Biogen treatment involves a passive immunisation technique. Their drug, called BIIB054 is currently in Phase II clinical trials for Parkinson’s (Click here to read a previous post on this topic and click here to learn more about the Phase II ‘SPARK study’ trial).

Which of these approaches is prasinezumab?

Like the Biogen treatment mentioned above, Prasinezumab is a passive immunisation approach.

Also known as PRX002, prasinezumab is an antibody that has been designed specifically to target the aggregated (toxic) form of alpha synuclein, and this treatment is intravenously injected into individuals with Parkinson’s (who have chosen to take part in the clinical trials).

What research has been previously conducted on prasinezumab?

Prasinezumab is derived from a mouse antibody called 9E4 which was originally developed by Elan Pharmaceuticals (now called Perrigo Company PLC). 9E4 was designed to bind to a specific region of human alpha synuclein protein (amino acids 118–126).

Preclinical research testing this antibody in models of Parkinson’s has been published:

Title: Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

Title: Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

Authors: Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M, Seubert P, Lee M, Goldstein J, Chilcote T, Games D, Schenk D.

Journal: Neuron. 2005 Jun 16;46(6):857-68.

PMID: 15953415

In this study, the researchers vaccinated genetically engineered mice (that generate high levels of human alpha synuclein protein) with human alpha synuclein protein. This caused an immune reaction in the mice and they began to generate antibodies targetting the protein. As a result of this, the researchers observed decrease in the accumulation of aggregated alpha synuclein in the brain.

They next injected antibodies targetting the human alpha synuclein protein into the genetically engineered mice, and they observed the same results. These findings suggested to the investigators that vaccination could be an effective method for reducing the accumulation of alpha synuclein aggregates.

In December 2012, the biotech firm Prothena spun out of Elan to further develop the alpha synuclein immunotherapy work (Source).

And the new company continued to develop their immunotherapy approach. That work included this research report:

Title: Reducing C-terminal-truncated alpha-synuclein by immunotherapy attenuates neurodegeneration and propagation in Parkinson’s disease-like models.

Title: Reducing C-terminal-truncated alpha-synuclein by immunotherapy attenuates neurodegeneration and propagation in Parkinson’s disease-like models.

Authors: Games D, Valera E, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Adame A, Patrick C, Ubhi K, Nuber S, Sacayon P, Zago W, Seubert P, Barbour R, Schenk D, Masliah E.

Journal: J Neurosci. 2014 Jul 9;34(28):9441-54.

PMID: 25009275 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers compared the efficiency of multiple antibodies targetting alpha synuclein. They reported that antibodies binding to one particular region (the C-terminus) reduced levels of the protein and its aggregation – which led to a rescuing of motor functions and Parkinson’s-like pathology in a mouse model of the condition.

With all of these preclinical results supporting the idea that immunotherapy could reduce the levels of alpha synuclein aggregation in models of Parkinson’s, Prothena felt confident about taking this treatment forward to clinical testing.

|

# # RECAP #2: Immunotherapy is a method of boosting the body’s immune system, to help it target potentially disease causing proteins. It has been used successfully in the treatment of cancer, and it is now being applied to Parkinson’s. Preclinical research suggests that carefully characterised antibodies – tiny proteins that target specific proteins – can be used to remove a toxic form of the alpha synuclein protein. # # |

In December 2013, Prothena and the Swiss Pharmaceutical company Roche signed a deal to co-develop and co-promote the development of immunotherapies for Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this). And based on the preclinical research described above, a Phase 1 clinical trial assessing the safety of PRX002 (also known as RO7046015; and later renamed prasinezumab) was initiated.

The results of that pilot work have been published:

Title: First-in-human assessment of PRX002, an anti-α-synuclein monoclonal antibody, in healthy volunteers.

Title: First-in-human assessment of PRX002, an anti-α-synuclein monoclonal antibody, in healthy volunteers.

Authors: Schenk DB, Koller M, Ness DK, Griffith SG, Grundman M, Zago W, Soto J, Atiee G, Ostrowitzki S, Kinney GG.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2017 Feb;32(2):211-218.

PMID: 27886407 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this first clinical study, the researchers recruited 40 healthy participants who were randomly assigned to one of 5 groups (n = 8 per group). Each participant in each of these groups was randomly given a single intravenous injection of the study drug PRX002. The doses were ascending (from 0.3mg/kg to 1, 3, 10, or 30). 6 participants in each group were given one of these doses and the last 2 were treated with a placebo treatment (Click here to read more about the details of this trial).

The results of the study were very encouraging as PRX002 was very well tolerated and there were no adverse events associated with it. In addition, there was a significant reduction in alpha synuclein levels in blood samples collected from the participants, suggesting that the treatment was doing what it was supposed to.

On the back of this safety study, a second Phase I trial of PRX002 was started. The results of that study were published in 2018:

Title: Safety and Tolerability of Multiple Ascending Doses of PRX002/RG7935, an Anti-α-Synuclein Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Title: Safety and Tolerability of Multiple Ascending Doses of PRX002/RG7935, an Anti-α-Synuclein Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Authors: Jankovic J, Goodman I, Safirstein B, Marmon TK, Schenk DB, Koller M, Zago W, Ness DK, Griffith SG, Grundman M, Soto J, Ostrowitzki S, Boess FG, Martin-Facklam M, Quinn JF, Isaacson SH, Omidvar O, Ellenbogen A, Kinney GG.

Journal: JAMA Neurol. 2018 Jun 18. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.

PMID: 29913017 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this Phase Ib study, the researchers recruited 80 mild to moderate idiopathic Parkinson’s (Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3; average age was 58 years) from July 2014 to September 2016 (Click here to read more about this trial). These participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or PRX002 (25 people received placebo and 55 were administered PRX002). Most of the participants used dopaminergic medications before starting the study (96.0% placebo vs 80.0% PRX002), did not have any family history of Parkinson’s (84.0% placebo vs 78.2% PRX002), and did not have a personal history of rapid eye movement sleep behavioural disorder (88.0% placebo vs 72.7% PRX002).

The study found that multiple intravenous injections of PRX002 every 4 weeks for 52 weeks was safe and well tolerated. There were no serious or severe treatment associated events reported. The ‘elimination half-life’ (the period when blood concentrations of the drug have halved) of the treatment was approximately 10.2 days. Infusions of PRX002 resulted in significant dose- and time-dependent reductions of free alpha synuclein in the blood (in some cases up to 97%).

The average levels of PRX002 getting across the blood-brain barrier – the protective membrane that surrounds our central nervous system – was measured at 9 weeks. The levels of PRX002 in cerebrospinal fluid was found to increase with dose, and was found to be approximately 0.3% of the levels found in the blood. While this is only a small fraction of the total amount of PRX002 in the body, the researchers at Prothena Therapeutics are confident (based on computer modelling from the preclinical models and Phase 1 studies) that levels of PRX002 in the brain meet what is needed for target engagement of the aggregated forms of alpha synuclein.

Unfortunately, there is no validated assessment available today for determining levels of aggregated alpha synuclein so it was not possible for Prothena to determine if there was any reduction of this form of alpha synuclein in the blood or brain fluid. They did note, however, that there was no statistically significant change in spinal fluid levels of free alpha synuclein was observed in the PRX002 treated groups, suggesting that in the brain at least the normal, un-aggregated form of alpha synuclein was not being tartgeted by PRX002.

The report concluded that results suggest that PRX002 is well tolerated and safe in people with Parkinson’s. And all of the data collected has provided useful information for designing and conducting a larger Phase II trial to assess whether PRX002 demonstrates any benefit in people with Parkinson’s during a period of 52 weeks.

|

# # # RECAP #3: Immunotherapy for the Parkinson’s associated protein alpha synuclein (using PRX002) has been reported to be safe and well tolerated in humans (with and without Parkinson’s). The collected data from two Phase I trials provided the information to conduct a larger Phase II trial which would offer the first chance to assess the efficiacy of PRX002. # # # |

So what do we know about the Phase II trial?

The Phase II trial of prasinezumab is called the PASADENA study (listed on the Clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03100149).

The study involves two parts:

Part 1 is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving approximately 300 people with Parkinson’s (all less than 2 years since diagnosis) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PRX002 in people with Parkinson’s over 52 weeks. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (1500 mg or 4500 mg of PRX002, or placebo treatment). The treatments was administered (via intravenous infusion) once every 4 weeks.

Part 1 of the study is completed and the announcement made this week is associated with this part of the trial.

Part 2 of the PASADENA study is a 52-week blinded extension phase in which participants from the placebo group of the study will be re-randomly assigned into one of two active doses on a 1:1 basis. This means that all participants will be on active treatment. Participants who were originally assigned to an active dose will continue at that same dose level for the additional 52 weeks.

Part 2 of the study is still ongoing.

Ok, so what do we know from the announcement?

So Roche has provided very little information beyond the note in their financial accounts (“Study did not meet its primary objective, but showed signals of efficacy“). One could speculate that someone in accounting accidentally inserted this sentence in the report without checking with the PR team (it has happened before with other companies). Alternatively, the company may simply be waiting for the end of Part 2 of the trial before commenting further.

Either way the disclosure has resulted in more questions than answers.

Prothena has kindly offered a few more details in their press release. But it is a rather complicated situation given that the PASADENA study is still ongoing (one is left wondering if the participants themselves were told about the results before they were announced).

According to the release, the results of Part 1 of the PASADENA study suggest that 52 weeks of prasinezumab treatment in Parkinson’s did not meet the primary objective (the pre-determined measure of whether the agent has an effect in slowing Parkinson’s progression), “but showed signals of efficacy. These signals were observed on multiple prespecified secondary and exploratory clinical endpoints“.

The PASADENA study was statistically designed (with 80% power and a one-sided alpha of 0.10) to detect a 35% reduction difference between the treatment and placebo groups (when comparing clinical assessments at baseline – before treatment – to week 52 of treatment).

What does any of that last sentence actually mean?

The statistical ‘Power’ of a clinical trial refers to the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis – that is to say, gaining a clear answer to the question being investigated. Guidelines suggest power should never be less that 80%.

A one-sided alpha of 0.10 refers to the possibility of a type I error – or the chance that you will reject the null hypothesis when it is actually true. In this case, it is only 10% – the conventional range for clinical trials alpha should be between 0.01 and 0.10. The lower, the better.

And what about detecting “a 35% difference”?

The primary endpoint used in this study was the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) total score (parts I, II and III). It is a widely used and most well characterised clinical rating system for PD. It is not an ideal tool, but it is the best we currently have.

The “35% difference” refers to the study being designed to confidently detect a 35% difference between the treatment and placebo groups.

At present, all we know is that the primary endpoint of the study was not met. Whether the prasinezumab-treated groups fared better or worse than the placebo-treated group is yet to be announced. We should not speculate beyond “primary endpoint of the study was not met”.

But what did they mean by “showed signals of efficacy”?

This is utterly not clear.

And given that there are 15 secondary outcomes listed on the clinicaltrials.gov website page for the PASADENA study (Click here to read more about this), it could literally mean anything.

The secondary endpoints include brain imaging (DaT-SPECT), date of starting of dopaminergic treatment, and a wide range of neurocognitive assessments. In addition, the study has several exploratory measures, which include a smartphone app that Roche has been developing.

Smartphone app?

Yes, in an effort to improve the monitoring and assessment of Parkinson’s (not just in clinical trials, but in general), Roche has put considerable effort into developing a smart phone app that allows for more frequent measures of Parkinson’s symptoms. And the company should be commended for undertaking this project – the tool generated and the data collected thus far will be an invaluable resource for researchers.

The results of a Phase I clinical assessment of this smartphone app has been published:

Title: Evaluation of smartphone‐based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson’s disease clinical trial

Title: Evaluation of smartphone‐based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson’s disease clinical trial

Authors: Lipsmeier F, Taylor KI, Kilchenmann T, Wolf D, Scotland A, Schjodt-Eriksen J, Cheng WY, Fernandez-Garcia I, Siebourg-Polster J, Jin L, Soto J, Verselis L, Boess F, Koller M, Grundman M, Monsch AU, Postuma RB, Ghosh A, Kremer T, Czech C, Gossens C, Lindemann M.

Journal: Mov Disord. 2018 Aug;33(8):1287-1297.

PMID: 29701258 (This report is OPEN ACCESS if you would like to read it)

In this study, the researchers at Roche conducted a 6‐month, phase Ib clinical trial involving 44 people with Parkinson’s completing 6 daily motor-associated tests using their smartphone. Their results were compared to an independent, 45‐day study conducted on 35 age‐matched healthy controls who also completed the 6 daily motor active tests.

Source: PMC

Source: PMC

The daily motor assessment tests included:

-

Sustained phonation – making a continuous “ahh” sound for as long as possible.

-

Balance task – standing still while having the smartphone in the trouser pocket.

-

Gait analysis task – with the smartphone in the trouser pocket, walking 20 yards, turning around, and returning to the starting point.

- Finger‐tapping – with the smartphone on a flat surface alternately tapping two touchscreen buttons as regularly as possible.

-

Resting tremor – seated, holding the phone in the palm of the hand resting on the lap.

-

Postural tremor – seated, holding the phone in their outstretched hand.

Watch this video for an explanation of these tests:

It will be interesting to see if some of the ‘signals of efficacy’ were being recorded by this novel research tool, but until the companies provide more information we certainly should not speculate about what they are referring to – especially as that PASADENA study is still ongoing – it is not expected to complete until February 2021 (and that date may be affected by the current COVID-19 situation).

We will have to wait and see.

So what does it all mean?

If current theories about how Parkinson’s is progressing are correct, then boosting the immune system to target proteins potentially associated with the neurodegenerative processes could represent a powerful approach for tackling the disease. An announcement this week regarding a clinical trial exploring one such technology (immunotherapy) has, however, provided very little clarity on how well this experimental treatment has fared or whether the theory is correct.

It would, however, be easy for the ‘I told you so’ objectors to the alpha synuclein theory to read too much into the press release and start suggesting that it is proof that our ideas on Parkinson’s progression are wrong (I just hope that they have some sensible alternative ideas rather than simply bringing negativity). It would also be easy for folks in the Parkinson’s community with high expectations for immunotherapy to think this treatment approach has “failed”. But given the scant pieces of information provided by the companies involved (while the trial is still ongoing), it would foolish and irresponsible of us to read too much into the offered statements and make too many assumptions. There are multiple immunotherapy clinical trials ongoing, those efforts should not be biased or paced in jeopardy based on a confused message from one particular trial.

I look forward to the final results of the PASADENA trial as there are a lot of important questions that needs to be explored in the wider data of the study (for example, I am very curious to hear if inflammatory markers are reduced in individuals treated with prasinezumab, or if they have improvement in their levels of constipation. Also I would like to know if there were any ‘super responders’ to the treatment and what is different about their Parkinson’s). Obviously, I am disappointed with the way this announcement of the top line results has been made, but I eagerly await some deeper analysis of the wider results and the outcome of Part 2 of the study.

But until they become available, it is wrong for anyone to over interpret (or over react) to what we currently have been told – which in truth is very little.

All of the material on this website is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

You can do whatever you like with it!

EDITOR’S NOTE: The information provided by the SoPD website is for information and educational purposes only. Under no circumstances should it ever be considered medical or actionable advice. It is provided by research scientists, not medical practitioners. Any actions taken – based on what has been read on the website – are the sole responsibility of the reader. Any actions being contemplated by readers should firstly be discussed with a qualified healthcare professional who is aware of your medical history. While some of the information discussed in this post may cause concern, please speak with your medical physician before attempting any change in an existing treatment regime.

Some of the companies mentioned in this post are publicly traded companies. That said, the material presented on this page should under no circumstances be considered financial advice. Any actions taken by the reader based on reading this material is the sole responsibility of the reader. None of the companies have requested that this material be produced, nor has the author had any contact with the companies beyond speaking with researcher employees about study data. This post has been produced for educational purposes only.

The banner for today’s post was sourced from Roche

Simon, some comments:

1) As always thank you for your prompt post and dissection of the data. I’ve been scouring the net since this release and over the last week the headlines read “failed” “flopped” and “misses”. You are one of the only sources to look at what’s out there and think about it. Again thank you.

2) As a participant in this study, I too am disappointed in how this information was shared. To take it a step further, it was outright stupid in my opinion. Part 2 is still ongoing, participants and evaluators are still venturing into COVID ridden hospitals to get infusions and take data. So again I think it’s pretty stupid to assume that the participant performance and evaluators score which contributes to the PRIMARY ENDPOINT will be the same after reading that the study drug already FAILED TO REACH THE PRIMARY ENDPOINT . Yes it’s open label, but come on… why take data if you’re going to randomly communicate like this given the strong placebo effect and potential evaluator bias?

3) I listened to most of the conference call. It was all COVID related, Roche products, responses etc. lots of talk about the brave Roche folks fighting COVID (nothing about brave participants btw). But the key point is they are in crisis mode much like the rest of the world and these comments may have been inserted months ago, passed through multiple inboxes and suddenly filtered through investor relations to get potential bad news out of the way while nobody is looking at page 133. My real point is that this was not targeted towards scientists, participants and patients, this was a message to investors not to get their hopes up too high or too low, and to wait for more data. It was not for us.

4) Finally, if any other participants are reading, I’d say keep the faith, carry on, and finish strong. Let’s get the scientists the best data we can and forgive the corporate communications folks who are working from home during this crisis thinking about their own problems. Simon is absolutely right not to overthink this. We may just need another year of data or 50% of us are super responders, or it cures constipation better than ex lax! Who knows?

Again thanks Simon. Your insights are spot on here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Participants were promised some early results last December, but finally heard (very little) when the study was presented at a virtual conference in late April. We finally received a small amount of direct information the next week through the clinics administering the trial. The good news out of that was that they would be carrying on a trial extension for several years after the current IIa study, AND that current participants would be eligible for inclusion. I think the inclusion of current participants is heavily due to the efforts of Parkinson’s organizations uniting to speak up for consideration and responsibility in their relationship with those who volunteer for trials. We can be grateful the trial was not ended because of the pandemic; that we have permission to skip/delay an appointment if there are pandemic safety concerns (in my trial, staff has been reduced to only 2-3 members who are able to isolate at home and leave only for office duties); and the good news for the Parkinson’s community that enough positive signs are showing to give cause for continuing to fund the trials. I, personally, am going to be most interested in the DATscan data showing changes in neuron loss. We have no word on that or on the blood markers they are/are not finding in all the “bloodletting.” The data monitors are a great idea, but the battery life of the watches is crummy. Mine now lasts about 5 hours between charges. Simon’s description of the tests used is better than what trial participants received.

Thank you again, Simon, for the excellent, thoughtful posts.

LikeLike