|

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable” This quote has been attributed to General Dwight D. Eisenhower (Click here for the full story of this quote), and while the sentence does not immediately make a whole lot of sense, it does apply to our discussion here regarding research in Parkinson’s. At the start of each year, it is a useful practise to layout what we are expecting and hoping to see in the world of Parkinson’s research over the next 12 months. This can help us better anticipate where ‘the battle’ may go, and allow us to prepare for things further ahead. Where it actually finishes is unpredictable, but where we currently stand will hopefully provide us with a useful measure. In this post, I will lay out what we believe the next 12 months holds for us with regards to the Parkinson’s-related research. And be warned: This is usually the longest post of the year.

|

Source: Protradeunited

Source: Protradeunited

In the introduction to last year’s outlook I wrote of the dangers of having expectations (Click here to read that post). A wise man (the great Charlie Munger) once said: If you want to lead a happy life, lower your expectations.

It is good advice, and as a rule, I try to follow it in life – I am a cup is completely empty kind of guy. I have no expectations, and so when anything happens – it is magic. I do have ambitions, but no expectations.

And others wrote about managing expectations in 2018 (Click here for a great example).

To put it plainly: Expectations are the primary cause of all disappointment.

Sage wisdom. Source: Unitystone

Sage wisdom. Source: Unitystone

And it is important, as we look ahead at the next 12 months of Parkinson’s research, we need to be very careful not to have too many (or to build up too many) expectations.

Right, now, with all of that said, it may now befuddle some readers that the theme of the 2019 SoPD outlook is ‘great expectations‘.

Let me explain:

Source: Fineartamerica

Source: Fineartamerica

Great expectations is a 19th century novel written by one Charles Dickens – it was the second to last novel he ever wrote.

In literary circles, Great Expectations is considered a Bildungsroman (from German, meaning: ‘Bildung’ – education, and ‘roman’ – story, novel). A bildungsroman is a story that focuses on the psychological growth of a character over time. It is a ‘coming of age‘ tale, in which the actual change in character is the centre of the story.

When I look at the big picture, I can’t help but think that 2018 was a ‘Bildungsroman’ year for Parkinson’s research.

There was an evolution. A growth spurt. A shifting away from many old ways, and an embracing of new and experimental ideas. It was a coming of age year for Parkinson’s research. And this shift showed itself in numerous ways.

For example:

- Recognition of patient advocacy – 2018 feels like the year that the research community finally started taking seriously the idea of involving people with Parkinson’s in the research process. Patient advocacy was always there (a la Tom Isaacs), but in 2018 something changed. Rather than simply being a ‘box-ticking exercise’ of asking a person with PD to read a grant funding application (for example), there was a very real recognition of the expertise within the affected community as well as the ‘lived experience’. This change showed itself in the dynamic and constructive discussions that developed at the Cure Parkinson’s Trust ‘Linked Clinical Trials’ meeting where the Parkinson’s researchers in the room actively sought the opinions of the PD advocates – some of whom had experience in the pharmaceutical industry or running clinical trials – useful knowledge (Click here to read more about this). It was also apparent in the efforts by advocates to push the research agenda, not only on social media but also at scientific research meetings (Click here to read an example of this). Social media has definitely helped (as in the case the Parkinson’s Research Interest Group or the Leicester Early Onset Parkinson’s Network – these guys are amazing!), but patient advocates are more involved in the research process now than ever.

- How cells die – in 2018 there was a great deal of research looking at the different forms of cell death involved with Parkinson’s. No longer was it acceptable to simply test a compound using neurotoxic agents with little disease relevance or to focus on ‘apoptosis‘ (programmed cell death). Now there are at least 14 different types of cell death, and several of them became the focus of Parkinson’s research in 2018 (these include: Parthanatos – Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic; or Pyroptosis (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic), with credible treatment candidates now being readied for clinical testing – more on this below.

- A shift from “too many patients, not enough clinical trials” – we are very quickly approaching a dilemma of too many experimental treatments entering clinical trials and not enough participants being available for recruitment. Volunteering to take part in a clinical trial is a personal choice, but as we have more clinical trials being initiated a lack of participants will slow down the process of bringing novel therapies to the clinic (as trial recruitment takes longer periods of time). But here again we have patient advocates stepping up to help solve the problem – individuals like Gary Rafaloff and Sue Buff – who maintain the Parkinson’s Trial Tracker, and also Kevin McFarthing who maintains a ‘therapies in development‘ database (it would be tremendous to see their efforts grow and blossom in this new year – their work has certainly been a major help in putting this outlook together).

These are just a couple of the shifts I noted in the coming of age year for Parkinson’s research. And I am saying this from the stand point of having been in the Parkinson’s research field for 15+ years now.

2018 actually felt different.

Putting the ‘bildungsroman’ year of 2018 in context

This change started, I’m guessing, with the Exenatide clinical trial news in late 2017.

In a Phase II placebo controlled, double blind clinical trial, this diabetes treatment demonstrated beneficial effects on motor scores in a cohort of people with Parkinson’s (Click here and here to read previous SoPD posts about this).

Very suddenly, this news shifted the needle within the Parkinson’s community – from ‘IF we find something that works’ closer to ‘WHEN we find something that works’.

And then came news of a clinical trial suggesting that high intensity exercise in Parkinson’s had a ‘nonfutile’ benefit for Parkinson’s (on motor features at least – click here to read a SoPD post about this research).

Source: Youtube

Source: Youtube

So as we entered 2018 with a great deal of optimism and excitement (and dare I say ‘expectations‘) in the field of Parkinson’s research. While research efforts in other neurodegenerative conditions were still struggling, Parkinson’s had managed to score a couple of goals. This situation natually had everyone in the Parkinson’s research community entering 2018 on a bit of a high.

And a lot was achieved in Parkinson’s research in 2018 – Click here for the SoPD 2018 highlights (Click here and here for other fantastic reviews from Parkinson’s News Today and Parkinson’s UK).

For example, we started 2018 with 41 genetic risk factors associated with Parkinson’s and we finished the year with 92 genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s (Click here to read a recent SoPD post on this topic). In addition, we started 2018 with the old fashioned ‘pill form’ L-dopa and we finished the year with inhalable L-dopa (Click here to read more about this). And of course a whole host of new clinical trials were initiated (more on this below).

Yes, we had our setbacks (for example the early closure of the Phase III clinical study of Inosine in Parkinson’s – Click here to read the press release about this).

But we plowed through them and discovered numerous novel experimental (potentially disease modifying) treatments that are now heading for the clinic.

But we plowed through them and discovered numerous novel experimental (potentially disease modifying) treatments that are now heading for the clinic.

For example:

- PARP inhibition – researchers demonstrated that Parkinson’s-associated alpha synuclein aggregates activate poly(adenosine 5′-diphosphate–ribose) (PAR) polymerase–1 (PARP-1), which leads to parthanatos cell death. In addition, they found that treating with clinically available PARP inhibitors significantly reduced levels of PAR in models of PD, which in turn resulted in less alpha synuclein aggregation. Investigations are now being made into the potential re-purposing of PARP inhibitors for clinical testing in Parkinson’s (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic).

- Stearoyl-CoA desaturase inhibition – researchers found that by reducing levels of unsaturated membrane lipids – via the inhibition of the oleic acid-generating enzyme ‘stearoyl-CoA-desaturase’ – in human neurons, they could protect the cells from alpha synuclein toxicity & enhance their survival. A biotech firm Yumanity is now seeking to start clinical testing of this approach in late 2019 (Click here for a SoPD post on this topic).

- HDAC4-modulating compounds – Researchers identified histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) as a regulator of disease progression in Parkinson’s models. Treating dopamine neurons in culture with HDAC4-modulating compounds like Tasquinimod – an allosteric inhibitor of HDAC4 – corrected Parkinson’s-related cellular phenotypes. Another potential drug for repurposing – Tasquinimod is being developed by Active Biotech for use in prostate cancer (Click here to read more about this).

- Inflammasome inhibition – Researchers found that alpha synuclein protein aggregates promote the activation of inflammatory processes (called the inflammasome) in the immune cells of the brain: the microglia. The researchers also reported that an orally administered NLRP3 inhibitor, called MCC950 improved motor performance and reduced neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and alpha synuclein accumulation in mouse models of Parkinson’s. MCC950 is being developed by a biotech firm called Inflazome who are seeking to start a Phase I clinical trial in early 2019 (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic).

In addition, new (and possibly better) versions of approaches already being clinically tested were proposed. For example, Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) receptor agonists (such as NLY01 – Click here to read an SoPD post on this topic) and c-Abl inhibitors (such as Radotinib – Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). More on these below.

And all of this has the ball rolling for a very busy year in Parkinson’s research in 2019.

Which brings us to the end of this rant/nonsensical preamble and to the business end of this post.

Let’s get into it:

Parkinson’s research in 2019

Ok, below is a non-exhaustive outline of what we should see in the next 12 months.

I am going to focus primarily on clinical trials of potentially disease modifying experimental therapies in this post, as this is what most readers are interested in (and a broader discussion of ‘all Parkinson’s research in 2019’ is too greater task).

And in keeping with last year’s outlook, I am going to frame this discussion around the statement that:

Any ‘cure for Parkinson’s’ is going to require three core components:

- A disease halting mechanism

- A neuroprotective agent

- Some form of cell replacement therapy

We will now explore each of these components individually and discuss what is happening with regards to clinical trials in 2019.

Let’s have a look at the first component of any “Cure for Parkinson’s”:

1. A disease halting mechanism

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative condition. Thus, the first and most critical component of any ‘cure’ for Parkinson’s involves a treatment that will slow down/halt the progression of the condition.

This can be done either directly or indirectly.

The direct approach

The direct approach involves treatments that target the underlying biology of the condition.

A direct approach in halting Parkinson’s, however, requires a fundamental understanding of how the condition is actually progressing. And if we are honest, we are not there yet – we still do not have a solid grasp of how Parkinson’s progresses over time.

We do, however, have some very good educated guesses as to what is happening, and there are also numerous clinical trials focused on direct approaches to halting Parkinson’s.

Most of the direct approach clinical trials involve a method called immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy involves boosting the body’s immune system to target specific toxic agents in the body. In the case of Parkinson’s, this approach is primarily being focused on different forms of the Parkinson’s associated protein, alpha synuclein.

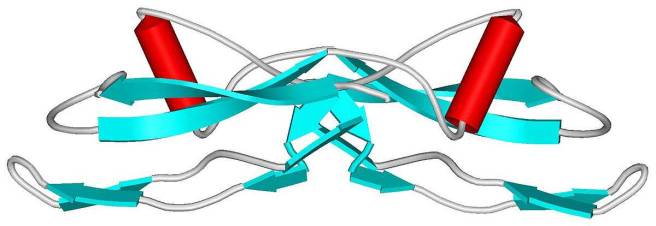

Antibodies. Source: Astrazeneca

This immunotherapy approach uses antibodies, which are Y-shaped proteins that act like alert flags for the immune system. Once enough antibodies bind to a particular object, the immune system will dispose of it. Antibodies target very specific structures, while ignoring everything else.

In Parkinson’s, the immunotherapy approaches are primarily involving antibodies that target the alpha synuclein protein.

Immunotherapy can be conducted in two ways:

- The body’s immune system can be encouraged to develop its own antibodies that target the toxic form of alpha synuclein (using active immunisation in the form of a vaccine); or

- Researchers can design antibodies themselves that specifically target the toxic form of alpha synuclein (while leaving the normal version of the protein alone), and then inject those antibodies into the body (passive immunisation)

Immunotherapy. Source: Acimmune

Immunotherapy. Source: Acimmune

There are now numerous biotech firms testing passive immunotherapy approaches in the clinic for Parkinson’s.

We are unlikely however to hear much major news in 2019 regarding this field of research – beyond the initiation of new Phase I & II studies and the completion of some Phase I safety trials, such as the Astrazeneca Phase I clinical study investigating single ascending doses of their immunotherapy MEDI1341 treatment in healthy volunteers, which finishes in November (Click here to read more about that study).

There are numerous other biotech firms with alpha synuclein targetting immunotherapy approaches – such as AC Immune (ACI-870), Proclara (NPT088), United Neuroscience (UB-312), Lundbeck (Lu AF82422; in collaboration with Genmab), and BioArctic Neuroscience (BAN0805, PD1601 & PD1602; in collaboration with AbbVie).

There are numerous other biotech firms with alpha synuclein targetting immunotherapy approaches – such as AC Immune (ACI-870), Proclara (NPT088), United Neuroscience (UB-312), Lundbeck (Lu AF82422; in collaboration with Genmab), and BioArctic Neuroscience (BAN0805, PD1601 & PD1602; in collaboration with AbbVie).

But in reality there are two main studies in the immunotherapy for Parkinson’s area that everyone has their eyes on.

The first is the SPARK study being conducted by the Pharmaceutical company Biogen.

This is a 2-year Phase II clinical trial that will test BIIB054 in an estimated group of 311 people with Parkinson’s. It will compare monthly infusions of 3 different doses of BIIB054 (250mg, 1250mg, or 3500mg) and these will be blindly compared to a placebo treated group (Click here to read more about this study and click here to read a SoPD post about the Phase I Biogen study results).

This is a 2-year Phase II clinical trial that will test BIIB054 in an estimated group of 311 people with Parkinson’s. It will compare monthly infusions of 3 different doses of BIIB054 (250mg, 1250mg, or 3500mg) and these will be blindly compared to a placebo treated group (Click here to read more about this study and click here to read a SoPD post about the Phase I Biogen study results).

The second main immunotherapy study is the PASADENA study – a Phase II clinical trial of RO7046015 (formerly called PRX002) being conducted by the pharmaceutical company Roche and biotech firm Prothena Biosciences.

This study involves two parts.

This study involves two parts.

Part 1 is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-arm study which will enrol approximately 300 people with Parkinson’s (all less than 2 years since diagnosis) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of RO7046015 in people with Parkinson’s over 52 weeks. Participants will be randomly assigned to one of three groups (1500 mg or 4500 mg of RO7046015 , or placebo treatment). The treatments will be administered via intravenous infusion once every 4 weeks.

Part 2 of this Phase II clinical trial is a 52-week blinded extension phase in which participants from the placebo group of the study will be re-randomly assigned into one of two active doses on a 1:1 basis (Click here to read more about this study).

Both of these studies are leading the pack of immunotherapy programmes for Parkinson’s, but they not expected to report their results before 2020, so we are unlikely to hear any news in 2019 (beyond an announcement of full recruitment to the study).

In addition to these passive immunotherapy treatments, there is one other company which is testing an active immunotherapy treatment in Parkinson’s. This is a vaccine for Parkinson’s, which targets the toxic form of alpha synuclein.

The company is called AFFiRiS.

And they are clinically trialing a vaccine treatment called ‘AFFITOPE® PD01A’ (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic).

We have not had any updates from AFFiRiS since May 2018. Thus, in 2019, we here at the SoPD HQ are hoping to get some news/updates regarding ongoing follow-ups of participants in their Phase I clinical studies, AND hear word of the initation of a larger Phase II clinical trial – particularly because their last press release had some ambigous sentences regarding study outcomes which still need to be clarified – see the bottom of this post to read about this).

Beyond the immunotherapy approaches, there are other experimental treatment methods that I am going to refer to as ‘direct’ because they go after the toxic form of alpha synuclein.

For example, there is an experimental drug called ENT-01 which prevent alpha synuclein from clustering and forming the toxic form of the protein.

ENT-01 is currently being clinically tested a company called Enterin Inc.

In 2017-2018, the company conducted the RASMET study, which was a Phase I safety clinical trial of ENT-01. ENT-01 is a derivative of a compound called squalamine (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). The issue with ENT-01 is that it does not cross the blood brain barrier – the membrane that surrounds the brain, protecting it from the nasty outside world. Thus, Enterin are focusing their clinical trial on Parkinson’s-associated constipation – can this drug reduce alpha synuclein aggregation in the gut and alleviate complaints like constipation.

In 2017-2018, the company conducted the RASMET study, which was a Phase I safety clinical trial of ENT-01. ENT-01 is a derivative of a compound called squalamine (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). The issue with ENT-01 is that it does not cross the blood brain barrier – the membrane that surrounds the brain, protecting it from the nasty outside world. Thus, Enterin are focusing their clinical trial on Parkinson’s-associated constipation – can this drug reduce alpha synuclein aggregation in the gut and alleviate complaints like constipation.

We are still waiting to hear the results of the Phase I RASMET study (Click here for the details), but the company announced the completion of enrollment in a Phase IIa ‘KARMET’ clinical study of ENT-01 in March of last year (Click here to read the press release), and just this week the company announced the initiation of a Phase IIb ‘KARMET’ clinical study of ENT-01 (Click here to read the press release about this). This progress suggests that the safety profile of the drug was acceptable for continuing on with the project. The Phase IIa study is scheduled to finish in late 2019 (Click here to read more about the trial). Hopefully we should get some news in 2019 regarding this set of clinical trials.

In addition, while ENT-01 does not cross the blood brain barrier, the company has another compound Trodusquemine which does get into the brain. So it would be very pleasing to hear news regarding the development of trodusquemine and perhaps the initiation of a Phase I clinical trial.

There is also NeuroPore (who are working in collaboration with UCB) to clinically test a small molecule inhibitor of alpha synuclein called NPT200-11.

In 2019, we are hoping to learn the results of their Phase I clinical trial (Click here to read more about that trial)

In 2019, we are hoping to learn the results of their Phase I clinical trial (Click here to read more about that trial)

That is where activities currently lie with the direct approach to slowing Parkinson’s.

We will now shift our attention to the:

The indirect approach

The indirect approach does not necessarily target the underlying mechanism of the condition, but rather attempts to slow progression by improving the ability of cells to clear toxic proteins. This generally involves boosting the waste disposal systems of the cell – in this manner, the cells can break down and dispose of excess alpha synuclein protein in the cell before it builds up and becomes toxic.

As you shall see below, there are numerous clinical trials testing different therapies of this nature.

And the one which we are looking forward to hearing the results of in 2019 involves a clinically available drug called Ambroxol:

Ambroxol. Source: Skinflint

In 2019, we will see the publication of the AIM-PD clinical trial, which has been supported by the Cure Parkinson’s Trust, the Van Andel Research Institute (USA) and the John Black Charitable Foundation (Click here to read more about the details of this study).

This study has investigated the tolerability of Ambroxol in people with Parkinson’s. Ambroxol is a commonly used treatment for respiratory diseases. Ambroxol promotes the clearance of mucus and eases coughing. It also has anti-inflammatory properties, reducing redness in a sore throat. But there is evidence that this drug can help in Parkinson’s.

This study has investigated the tolerability of Ambroxol in people with Parkinson’s. Ambroxol is a commonly used treatment for respiratory diseases. Ambroxol promotes the clearance of mucus and eases coughing. It also has anti-inflammatory properties, reducing redness in a sore throat. But there is evidence that this drug can help in Parkinson’s.

Researchers believe that Ambroxol could be useful with Parkinson’s in two ways:

1. Ambroxol is believed to triggers exocytosis of lysosomes (Source). Exocytosis is the process by which waste is exported out of the cell. Lysosomes are the bags of digestive that rubbish and waste is put into inside a cell for recycling. by encouraging lysosomes to undergo exocytosis and spit their contents out of the cell – digested or not – Ambroxol allows the cell to remove waste effectively and therefore function in a more normal fashion.

Exocytosis. Source: Socratic

2. Ambroxol has been shown to increase levels of an enzyme called glucocerebrosidase (or GCase) in the brain (Source). GCase is involved with the breaking down of proteins in the lysosome. GCase is generated from instructions provided by a gene called GBA1. Mutations in this gene are one of the most common genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s.

So by administering Ambroxol to people with Parkinson’s, researchers are hoping to raise levels of GCase to help digest proteins and increase the excretion of this waste from cells. This would ideally keep cells healthier for longer and slow down the progression of Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this).

We are also expecting to hear the results of a second Ambroxol study, which is being conducted by the Lawson Health Research Institute (and the Weston Foundation) in Canada. This is a phase II, 52 week trial of Ambroxol in 75 people with Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (Click here to read more about this trial). In this randomised, double blind study, two doses of Ambroxol were tested – a high dose (1050 mg) and a low dose (525 mg) – as well as a placebo treated group.

We are awaiting results/news regarding both of these Ambroxol studies in 2019.

And on the GBA1 front, we will be hoping to hear some news from the clinical trial of Venglustat (formerly known as GZ/SAR402671 & Ibiglustat) which is being conducted by the biotech company Sanofi Genzyme.

As I mentioned above, genetic variations in the GBA1 gene are one of the most common genetic risk factors associated with Parkinson’s, and it results in a reduction in the activity of the waste disposal system of cells. This trial, called “MOVES-PD” (Click here to read more about the trial) is a phase II clinical study that will be involve in two parts:

As I mentioned above, genetic variations in the GBA1 gene are one of the most common genetic risk factors associated with Parkinson’s, and it results in a reduction in the activity of the waste disposal system of cells. This trial, called “MOVES-PD” (Click here to read more about the trial) is a phase II clinical study that will be involve in two parts:

- A dose escalation study to determine safety in early-stage GBA-associated Parkinson’s.

- A randomised, double blind study of efficacy of Venglustat, as compared to placebo in early-stage GBA-associated Parkinson’s

Venglustat is a glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor, which would block the production of the proteins that GBA helps to break down thus reducing the work required for this enzyme. Preclinical results look very promising (Click here to read some of the research on this), and while this study is not expected to report until after 2022, we are expecting news regarding the tolerability of this new drug to be released around the time of the Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s 2019 meeting in March.

Another ‘indirect’ approach to slowing Parkinson’s involves a re-purposed cancer drug called Nilotinib.

Nilotinib. Source: William-Jon

Nilotinib. Source: William-Jon

Nilotinib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor, that has been approved for the treatment of imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Previous research suggests that Nilotinib has beneficial effects in models of Parkinson’s and a Phase I study provided interesting results (Click here to read more about this). But exactly how Nilotinib is having this positive effect is still not clear. It is believed to be increasing the levels of waste recycling inside cells.

There are currently two Phase II double blind clinical trials of Nilotinib being conducted:

- PD Nilotinib, which is being conducted at Georgetown University in Washington DC (Click here for the more details about this study). This study involves 75 participants and will involve two parts:In the first part of the study, one third of the participants receiving a low dose (150mg) of Nilotinib, another third receiving a higher dose (300mg) of Nilotinib and the final third will receive a placebo drug (a drug that has no bioactive effect to act as a control against the other two groups). The outcomes will be assessed clinically at six and 12 months by investigators who are blind to the treatment of each subject. These results will be compared to clinical assessments made at the start of the trial.In the second part of the study, there will be a one-year open-label extension trial, in which all participants will be randomised given either the low dose (150mg) or high dose (300mg) of Nilotinib. This extension is planned to start upon the completion of the first part (the placebo-controlled trial) to evaluate Nilotinib’s long-term effects.

- NILO-PD, which is being conducted at the Feinburg School of Medicine at Northwestern University (Click here for the more details about this study). This study will involve two groups (or cohorts) of participants.The treatment will firstly be given to a first cohort of 75 people everyday for six months, during which the participants will be closely monitored. Following the treatment phase there will be an 8 week follow up period (during which all treatments are stopped), in order to determine Nilotinib’s safety and tolerability. Trial participants will be tested on their motor and cognitive abilities, and they will give sampled (i.e., blood and spinal fluid) for biological testing. All of these tests will provide the investigators with data with which to evaluate the potential impact of Nilotinib on Parkinson’s symptoms and the disease progression.If the drug is shown to be safe in this first cohort, a second trial is planned to be immediate initiated which would test Nilotinib in a second cohort of 60 people with early Parkinson’s disease. These subjects would be given the highest tolerated daily dose of Niltotinib (based on the results of the first study) or a placebo for 12 months. The same measurements (eg. biological samples) would be applied to this study as well. This study is supported by the Michael J Fox Foundation and the Cure Parkinson’s Trust.

Both of these studies are not expected to provide results until 2020.

But in 2019, we are expecting to hear news of the commencement of additional clinical trials investigating small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are very similar to Nilotinib. Chief among these is K0706 which is being developed by Sun Pharma Advanced Research Company (or SPARC).

SPARC has very recently initiated an international Phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of K0706 in 500+ people with early Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this study). This study is expected to finish in 2021.

SPARC has very recently initiated an international Phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of K0706 in 500+ people with early Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this study). This study is expected to finish in 2021.

In 2019, we will also hopefully learn about the initiation of a clinical trial of a Nilotinib-like drug called Radotinib which is being developed by South Korean firm Ilyang Pharmaceutical.

![]() Radotinib is currently in phase III testing for chronic myeloid leukemia (Click here to learn more about that trial). Thus, we already have a lot of information about use of this drug in humans, which could make the clinical testing of it quicker in the case of Parkinson’s. Plus, and this is the important detail – Radotinib appears to access the brain better than Nilotinib which could mean that lower doses of the drug can be used in people with Parkinson’s (reducing the chances of side effects). We will be waiting for news from Ilyang Pharmaceutical, not holding our breath, but waiting.

Radotinib is currently in phase III testing for chronic myeloid leukemia (Click here to learn more about that trial). Thus, we already have a lot of information about use of this drug in humans, which could make the clinical testing of it quicker in the case of Parkinson’s. Plus, and this is the important detail – Radotinib appears to access the brain better than Nilotinib which could mean that lower doses of the drug can be used in people with Parkinson’s (reducing the chances of side effects). We will be waiting for news from Ilyang Pharmaceutical, not holding our breath, but waiting.

Another biotech company, Inhibikase Therapeutic, is hoping to start clinical testing of their Nilotinib-like drug, called IkT-148009 in 2019 (Click here to read more about this). And we will also be waiting for news from 1ST Biotherapeutics regarding the start of clinical testing for their small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor called 1ST-102.

The take-home-message here:

A great deal of activity expected in the ‘Nilotinib’ realm in 2019.

This post is very quickly starting to feel like a shopping list of clinical trials.

Still with me?

Is it still interesting? I hope so – we have a loooong way to go!

We continue:

Another clinical trial of a waste disposal boosting therapy that I will be very interested to read any announcements about in 2019 is being conducted by a biotech firm called Lysosomal Therapeutics.

This company has just completed the Phase Ia clinical studies of their experimental drug LTI-291, which is an activator of the Glucocerebrosidase enzyme (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic). LTI-291 is targeted at GBA-associated Parkinson’s, but the first clinical study involved healthy volunteers (Click here to read more about this study – some knowledge of Dutch may help with regards to the details here).

This company has just completed the Phase Ia clinical studies of their experimental drug LTI-291, which is an activator of the Glucocerebrosidase enzyme (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic). LTI-291 is targeted at GBA-associated Parkinson’s, but the first clinical study involved healthy volunteers (Click here to read more about this study – some knowledge of Dutch may help with regards to the details here).

The results have not been published yet, but the company’s website suggests that the “study established an excellent safety and tolerability profile in normal human volunteers” (Click here to read more). They have now begun the Phase Ib clinical trial to test safety and tolerability of LTI-291 in 15 people with Parkinson’s who carry a heterozygous mutation in the GBA1 gene (Click here to read more about this trial). I am hoping that we will hear the results of this trial as well in 2019.

The Lysosomal Therapeutics clinical trial is being supported by the Silverstein Foundation – which is focused on finding curative treatments for GBA-associated Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about the Foundation).

Another company supported by the Silverstein foundation that I am keen to hear news from in 2019 is Arvinas.

Another company supported by the Silverstein foundation that I am keen to hear news from in 2019 is Arvinas.

This is a Connecticut-based biotech firm whose technology focuses on developing compounds that degrade toxic intracellular protein using proteolysis targeting chimera (or PROTAC) technology. This system can help reduce levels of toxic alpha synuclein within a cell in the Parkinsonian brain for example. This video explains how PROTAC works:

This is a Connecticut-based biotech firm whose technology focuses on developing compounds that degrade toxic intracellular protein using proteolysis targeting chimera (or PROTAC) technology. This system can help reduce levels of toxic alpha synuclein within a cell in the Parkinsonian brain for example. This video explains how PROTAC works:

In March 2018, the company entered into a research agreement with The Silverstein Foundation, focused on efforts to develop a blood brain barrier-penetrant, alpha synuclein-targeting PROTAC.

On the 4th January (2019), Arvinas announced that the US FDA had given the company permission to begin clinically testing their first PROTAC protein degrader in humans – ARV-110 is an oral androgen receptor protein degrader for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Arvinas expects to begin a Phase I clinical trial for ARV-110 in the first quarter of this year (Click here to read the press release). Hopefully, clinical testing of an alpha synuclein-targeting PROTAC will not be too far behind.

And Arvinas is not the only company testing this approach. Another PROTAC-like approach for neurodegenerative conditions is being attempted by a company called C4 Therapeutics.

This biotech firm uses a degradation tag (dTAG) for targeting pathogenic proteins that need to be disposed of (Click here to read recent research about this). Just a couple of days into 2019, C4 Therapeutics and the pharmaceuticals company Biogen announced a strategic collaboration.

This biotech firm uses a degradation tag (dTAG) for targeting pathogenic proteins that need to be disposed of (Click here to read recent research about this). Just a couple of days into 2019, C4 Therapeutics and the pharmaceuticals company Biogen announced a strategic collaboration.

The two companies want to investigate the use of C4T’s novel protein degradation technology to discover and develop new treatments for neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s (Click here to read the press release). It will be interesting to see if this collaboration bears some fruit before years end.

The two companies want to investigate the use of C4T’s novel protein degradation technology to discover and develop new treatments for neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s (Click here to read the press release). It will be interesting to see if this collaboration bears some fruit before years end.

And C4 Therapeutics was not the only Parkinson’s-related business deal that Biogen has done recently. The same day that Biogen announced the C4 deal, they also put out a press release about a strategic hook up with a company called Skyhawk (Click here to read the press release).

It is not clear whether this second deal for Biogen has anyhing to do with Parkinson’s (the press release only states “multiple sclerosis, spinal muscular atrophy and additional neurological disorders”) and the company’s lead oncology treatment is not yet in clinical testing, but I’ll be watching them in 2019 for any news – a very interesting company (using small molecule therapeutics to selectively target and correct RNA expression).

It is not clear whether this second deal for Biogen has anyhing to do with Parkinson’s (the press release only states “multiple sclerosis, spinal muscular atrophy and additional neurological disorders”) and the company’s lead oncology treatment is not yet in clinical testing, but I’ll be watching them in 2019 for any news – a very interesting company (using small molecule therapeutics to selectively target and correct RNA expression).

A third Silverstein foundation project that I will be hoping to hear some news about this year is a biotech firm called Prevail Therapeutics.

In March 2018, the company announced a $75 million Series A financing to advance gene therapy-based treatments in Parkinson’s. But in 2017, the company entered into an exclusive worldwide license agreement with REGENXBIO to develop and commercialise gene therapy products using REGENXBIO’s NAV AAV9 vector for the treatment of Parkinson’s and other related neurodegenerative conditions. These viruses are remarkably more robust and selective compared to previous generations.

In March 2018, the company announced a $75 million Series A financing to advance gene therapy-based treatments in Parkinson’s. But in 2017, the company entered into an exclusive worldwide license agreement with REGENXBIO to develop and commercialise gene therapy products using REGENXBIO’s NAV AAV9 vector for the treatment of Parkinson’s and other related neurodegenerative conditions. These viruses are remarkably more robust and selective compared to previous generations.

In June 2018, the U.S. FDA granted Fast Track designation to REGENXBIO for RGX-111, which is a novel, one-time investigational treatment for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I (MPS 1). MPS 1 is a rare lysosomal storage disease caused by deficiency of an enzyme called iduronidase (IDUA). RGX-111 is a NAV AAV9 vector that is designed to deliver the human iduronidase (IDUA) gene directly to cells in the brain (Click here to read the press release and learn more about this study). One can assume that Prevail Therapeutics is planning something similar for GBA-associated Parkinson’s – by using a virus to insert a good copy of the GBA gene into brain cells, will this company be able to slow down GBA-associated Parkinson’s? I guess this really belongs in the ‘direct approach’ basket, but we’re not going back now (I’ll correct this next year!). Back on message: I will be very interested to hear anything related to Prevail Therapeutics in 2019.

Now, if one of these ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’ approaches is able to slow or halt Parkinson’s, the next requirement in a ‘cure’ for Parkinson’s is:

2. A neuroprotective agent

Once a drug or a treatment has been determined to slow down the progression of Parkinson’s, it will be necessary to protect the remaining cells and provide a nurturing environment for the third part of the ‘cure’ (Cell replacement therapy – more on that below).

This is where the second component of any curative approach for Parkinson’s comes into effect.

Neuroprotection is the area of research that has had the most attention over the years. Drug companies have employed vast resources in this area in the hope of discovering a treatment which works across conditions (think Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, etc).

In the ‘neuroprotection’ section, top of the list of news that we will be looking for in 2019 is the initition of a Phase III clinical trial for Bydureon/Exenatide.

Glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a major area of research in Parkinson’s. With the interesting results of the Phase II Exenatide trial reported in 2017 (Click here and here to read previous SoPD posts about this), there will be serious expectations that will need to be carefully managed with the start of the Phase III study.

In addition to Exenatide, there are ongoing clinical trials for other GLP-1 agonists, for example the Lixisenatide trial in France (Click here and here for more information on this study), and the Liraglutide trial in California (Click here and here to read more about this study). Neither of these two ongoing GLP-1 agonist studies will not be reporting their results in 2019.

There is also a recently initiated clinical trial of a new formulation of Exenatide called Semaglutide in Parkinson’s. This study is being conducted in Norway by the Danish company biotechfirm Novo Nordisk.

This Phase II study will involve 120 participants, who will take either Semaglutide or placebo for 24 months in a double blind stage, before a further 24 months of open label assessments. The study is not expected to report results before 2024 (Click here to read more about this study).

This Phase II study will involve 120 participants, who will take either Semaglutide or placebo for 24 months in a double blind stage, before a further 24 months of open label assessments. The study is not expected to report results before 2024 (Click here to read more about this study).

In 2019, we will hopefully also see some news regarding a clinical trial starting for a new GLP-1 receptor agonist called NLY01, which is being developed by Neuraly Inc.

NLY01 has been tested in preclinical models of Parkinson’s and been found to have beneficial neuroprotective properties, via the microglial cells (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). Most impressive is the half-life of 38 hours in mice and 88 hours in primates. This is impressive compared to Exenatide (Byetta) which has a half-life of just 2.5 hours in primates. The half-life of a drug is the time required for the concentration of the drug to decrease by half in the body.

NLY01 has been tested in preclinical models of Parkinson’s and been found to have beneficial neuroprotective properties, via the microglial cells (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). Most impressive is the half-life of 38 hours in mice and 88 hours in primates. This is impressive compared to Exenatide (Byetta) which has a half-life of just 2.5 hours in primates. The half-life of a drug is the time required for the concentration of the drug to decrease by half in the body.

We will be looking for news of clinical trial initiation of NLY01 in 2019.

As with the ‘Nilotinib’ realm, there will be a lot of activity in the GLP-1 receptor agonist realm as well.

Still with me?

We’re not even half way yet. So pace yourself.

Another item on the list of ‘neuroprotective’ news that we will be looking for in 2019 is the publication of the Phase II GDNF clinical trial results. The results have been expected for some time (Click here to read more about this), and there is likely to be a lot of discussion about them when they are released.

Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (or GDNF) is a neurotrophic factor – that is a supportive/nurturing chemical for the brain – which has had a long roller coaster-like history with Parkinson’s. The Phase II clinical trial supported by Parkinson’s UK and The Cure Parkinson’s Trust failed to achieve its primary end point, but it will be interesting to see what other results were found by the investigators.

GDNF. Source: Wikipedia

GDNF. Source: Wikipedia

Despite the set back with this GDNF trial, there is a gene therapy clinical trial of GDNF that may be initiated in California in 2019. This study was originally supposed to be conducted on the east coast, but it has been shifted to the west coast, and it will hopefully be starting in the next 12 months. This Phase I study will involve an AAV virus being injected into the brain, which will infect cells with the DNA required for the production of GDNF – causing cells in a particular region of the brain to start producing GDNF (Click here to learn more about this trial). We will be keeping an ear to the ground for information relating to this study.

And there is also another ongoing neurotrophic factor study that we will be watching very closely in 2019. The cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor (CDNF) clinical trial being conducted in Finland and Sweden is scheduled to finish this year, and we will hopfully get some news about that study. This study is being run by the biotech firm, Herantis.

The Phase I/II study is evaluating the safety and tolerability of CDNF in people with Parkinson’s. Similar to the Phase II GDNF study, the drug is injected directly into the brain using an implanted canular system. One-third of the participants have received monthly infusions of placebo and two-third of the participants have received monthly infusions of either mid- or high-doses of CDNF for 6 months (Click here to read more about this trial). An extension study of this trial has recently been initiated (Click here to read more about that study).

The Phase I/II study is evaluating the safety and tolerability of CDNF in people with Parkinson’s. Similar to the Phase II GDNF study, the drug is injected directly into the brain using an implanted canular system. One-third of the participants have received monthly infusions of placebo and two-third of the participants have received monthly infusions of either mid- or high-doses of CDNF for 6 months (Click here to read more about this trial). An extension study of this trial has recently been initiated (Click here to read more about that study).

While we will have to wait until next year to learn the topline results from this study, the safety/tolerability data from this trial are going to be presented the Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s 2019 meeting in March.

In addition to these results, we will also hopefully hear more news from the company Herantis about their efforts to develop a non-invasive form of CDNF. This would be some sort of pill form of the treatment, which does not require tubes to be implanted in the brain (Click here to read more about this).

Ok, what follows is going to be a “shopping list” of neuroprotective clinical trials.

There is simply no way of avoiding it.

We have a long list of therapies currently being clinically tested and this SoPD post will never end if we go into too much detail.

So here they are (in no particular order of preference and I’ll number them to aid in not getting lost):

1. This year the results of the STEADY-PD III study (which is being conducted by the Parkinson Study Group) will be announced. This Phase III clinical trial involves 300+ participants and is testing the calcium channel blocker ‘Isradipine’ in Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this).

Here at the SoPD website, we are very keen to see the results of this trial.

2. One neuroprotective clinical trial I was curious to hear more about actually had its results published as I was finishing up this post. South Korean firm Kainos Medicine has been conducting a clinical study evaluating KM-819 – a small molecule inhibitor for FAF1. FAF1 is a protein involved with cell death, so by inhibiting/blocking it the researchers are investigating whether this could be beneficial in Parkinson’s.

This was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-escalation study in healthy volunteers, that found that the drug was safe/tolerable with no drug-related SAEs (Click here to read more about this). It will be interesting to see if a Phase II clinical trial is initiated in 2019.

3. Another experimental compound I am looking forward to learning more about in 2019 is EPI-589.

BioElectron (formerly Edison Pharmaceuticals) is a biotech firm that is working on mitochondrial functioning and they have conducted a Phase II open label, safety trial for the evaluation of EPI-589 in people with early onset genetic forms of Parkinson’s and also idiopathic Parkinson’s (Click here to learn more about this trial). We should learn the results of this clinical trial in 2019.

And this trial is particularly interesting given the announcement in September 2018 of positive results for an open label Phase II clinical trial of EPI-589 in motor neurone disease/ALS. This study was assessing safety, tolerability, and disease biomarker effect, and the results “provide a strong rationale for the continued development of EPI-589” in ALS (Click here and here to read more about this and click here for the details of the study).

4. In March of 2019, the Korean pharmaceutical company Dong-A ST Co. is scheduled to complete a Phase II clinical trial of DA-9805 in people with Parkinson’s.

DA-9805 is a combination of compounds extracted from three dried plant materials (Moutan cortex, Angelica Dahurica root, and Bupleurum root) in a 1:1:1 mixture, which has demonstrated neuroprotective properties in models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about that). Dong-A ST Co. has conducted a Phase IIa, randomised, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate not only the safety & tolerability of DA-9805, but also the efficacy of the drug in people with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this trial).

DA-9805 is a combination of compounds extracted from three dried plant materials (Moutan cortex, Angelica Dahurica root, and Bupleurum root) in a 1:1:1 mixture, which has demonstrated neuroprotective properties in models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about that). Dong-A ST Co. has conducted a Phase IIa, randomised, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate not only the safety & tolerability of DA-9805, but also the efficacy of the drug in people with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this trial).

I am quietly very intrigued by this study and look forward to seeing the results.

5. A clinical trial evaluating a compound called CuATSM in Parkinson’s will be finishing in early 2019, and we may have news of the outcomes before the end of the year. This multicenter, open-label, phase I study was run by Collaborative Medicinal Development Pty.

The study was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, participants received escalating daily doses of CuATSM to establish a recommended dose for the phase II part of the study. In the second part of the study, an expansion cohort of 20 people with Parkinson’s were treated to confirm tolerability and assess preliminary evidence of efficacy over 28 days of treatment (Click here to read more about this study).

CuATSM is a drug that is currently under clinical investigation as a brain imaging agent for detecting hypoxia (damage caused by lack of oxygen – Click here to read more about this). CuATSM is also a highly effective scavenger of a chemical called ONOO, which can be very toxic and it also blocks the aggregation of alpha synuclein. And there is evidence of beneficial effects of CuATSM in models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read an example), so this trial is of interest.

And this trial is also particularly interesting given the very recent announcement of positive results (again) in an open label Phase I/II clinical trial of CuATSM in motor neurone disease/ALS (Click here to read more about this).

6. In 2019, we will also be awaiting the results of the next step in the clinical testing of the LRRK2 inhibitor, DNL-201 by the biotech firm Denali Therapeutics.

This is an entirely new class of treatment for Parkinson’s (Click here to learn more about this), and a lot of eyes are watching this study.

It is a 28-day, randomised, placebo controlled Phase 1b clinical trial in people with mild to moderate Parkinson’s, with and without genetic LRRK2 mutations (Click here to read more about the details of the study). The purpose of the study is to evaluate safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (the effect of body on the drug) and pharmacodynamics (the effect of drug on the body) of DNL-201. In addition, the researchers will be evaluating target and pathway engagement – using different biomarkers – following multiple oral doses of DNL201 (or placebo). There will also be an assessment of certain clinical endpoints.

The 30 participants enrolled in the study will be randomly assigned to receive either a low dose of DNL201, a high dose of DNL201, or placebo. Both the participants and investigators will be blind to who is receiving which treatment, and the results of the study should be available by the end of 2019.

I am also just a little bit curious to learn more about the recently reported collaboration between Denali Therapeutics and SIRION Biotech, which is a viral vector gene therapy company. (Click here to read the press release). Very curious.

We are also keen to learn more in 2019 about the efforts of the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and their LRRK2 inhibitor programme.

We are also keen to learn more in 2019 about the efforts of the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and their LRRK2 inhibitor programme.

The company signed a 4 years partnership with the DNA analysis company 23andMe in 2018. As part of that deal, GSK is contributing its LRRK2 inhibitor program, and they maybe hoping to use 23andMe’s database of people who know their LRRK2 genetic status. Such access may help their Parkinson’s clinical program enroll participants quicker in their planned clinical trial of their LRRK2 inhibitor (Click here to read more about this).

In addition, GSK has initiated a LRRK2 observation clinical study at King’s College in London. This study will involve 75 participants (25 with LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s, 25 with non-LRRK2 Parkinson’s, and 25 healthy control subjects), and the researchers will be assessing a wide range of biomarkers over 12 months (Click here to read more about this). It will be interesting to see how things develop there.

And still on the LRRK2 front, I will be looking out for new entrants in the area of LRRK2 inhibitors, for example Cerevel Therapeutics.

This is a new biotech firm that was started last year by Bain Capital and the Pharmaceutical company Pfizer (Click here to read more about this). Cerevel has taken on many of the neuroscience treatments that Pfizer was clinically testing until it shut down their neuroscience division in early 2018 (Click here to read more about this). In addition to those clinically tested assets, Cerevel have also quietly added ‘LRRK2 inhibitor’ to their preclinical ‘lead development’ area of research. So we will be looking for news regarding this in 2019.

This is a new biotech firm that was started last year by Bain Capital and the Pharmaceutical company Pfizer (Click here to read more about this). Cerevel has taken on many of the neuroscience treatments that Pfizer was clinically testing until it shut down their neuroscience division in early 2018 (Click here to read more about this). In addition to those clinically tested assets, Cerevel have also quietly added ‘LRRK2 inhibitor’ to their preclinical ‘lead development’ area of research. So we will be looking for news regarding this in 2019.

7. A clinical trial in Taiwan investigating Lovastatin as a neuroprotective treatment for early stage Parkinson’s will be finishing in late 2019, so we might (if we are lucky) hear news from this (Click here to read more about this study).

Lovastatin is a statin drug – a cholesterol lowering drug – that has demonstrated neuroprotective properties in preclinical models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). It will be interesting to see the results of this Phase II single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial, as it may give us some insights into the potential results of a much larger clinical study (300+ people) of statins in Parkinson’s – the PD-STAT study – being conducted here in the UK (Click here to learn more about this study). PD-STAT is scheduled to finish in late 2020.

8. At the end of 2019, the Deferiprone study will be finishing and while the results will not be available until 2020, we may get some news if we are lucky. This international trial is being conducted by ApoPharma.

Deferiprone is a treatment that is clinically used to remove excess iron in people who have particular blood conditions. In this large Phase II study of 140 people with Parkinson’s, the investigators have been assessing whether twice-daily treatment for 9 months can have beneficial effects on the condition (Click here to read more about the details of this study).

Deferiprone is a treatment that is clinically used to remove excess iron in people who have particular blood conditions. In this large Phase II study of 140 people with Parkinson’s, the investigators have been assessing whether twice-daily treatment for 9 months can have beneficial effects on the condition (Click here to read more about the details of this study).

This study is supported by a previous clinical study whose results suggested a large analysis was required (Click here to read that study).

9. In 2019, we will see the completion of a clinical trial of Ursodeoxycholic acid (or UDCA) which has been conducted at the University of Minnesota.

This Phase I open label study was designed to assess the safety/tolerability of increasing doses of UDCA, and whether the treatment will result in increased levels of ATP in the brains of individuals with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this). ATP (or Adenosine Triphosphate) is the fuel which cells run on, and previous preclinical research has suggested that this compound is neuroprotective in models of Parkinson’s. A poster of this study was presented at the Grand Rapids meeting in September, and the safety/tolerability data looked very encouraging.

And as this clinical trial reports their results, another clinical trial of UDCA is kicking off in Sheffield (UK).

The Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience (SITraN) has conducted a lot of interesting Parkinson’s research (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this), including some of the preclinical UDCA research in Parkinson’s models. The researchers there will be initating a large clinical trial of UDCA in 2019 – we will have more details on this in a future post.

The Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience (SITraN) has conducted a lot of interesting Parkinson’s research (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this), including some of the preclinical UDCA research in Parkinson’s models. The researchers there will be initating a large clinical trial of UDCA in 2019 – we will have more details on this in a future post.

In addition to the UDCA study in Sheffield, we will be looking for other Parkinson’s research-related news from this city in 2019. That news will hopefully be coming from the Parkinson’s UK’s virtual biotech firm called Keapstone Therapeutics.

Keapstone was set up in late 2017 to develop neuroprotective therapies for Parkinson’s that are focused on compounds that trigger a cellular defence system that helps protect brain cells from oxidative stress (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this). Will we see research news from Keapstone in 2019?

Keapstone was set up in late 2017 to develop neuroprotective therapies for Parkinson’s that are focused on compounds that trigger a cellular defence system that helps protect brain cells from oxidative stress (Click here to read a previous SoPD post about this). Will we see research news from Keapstone in 2019?

10. In June last year, Australian-based Prana Biotechnology initiated a clinical trial of their drug PBT434 in healthy individuals.

This was a Phase I study evaluating the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of this treatment, after single and multiple oral dose administration. It would be good to hear about a clean set of results this year and the commencement of a Phase I/II clinical trial in people with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this and click here for a previous SoPD post on this topic).

This was a Phase I study evaluating the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of this treatment, after single and multiple oral dose administration. It would be good to hear about a clean set of results this year and the commencement of a Phase I/II clinical trial in people with Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about this and click here for a previous SoPD post on this topic).

In addition to these clinical trials which are finishing in 2018/19, there are a large number of ‘neuroprotective’ study that are hopefully being initiated during this time, which are of great interest to the hacks here at the SoPD HQ.

A clinical trial of Nicotinamide Riboside (a form of Vitamin B3) is just starting in Norway – the ‘NOPARK’ Study. We have previously discussed the biology of Nicotinamide Riboside (Click here to read that SoPD post), and this trial will be an interesting test of this compound in Parkinson’s. It is a randomised, double-blind trial involving 200 participants with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s, who will be randomly assigned in an 1:1 ratio to either nicotinamide riboside or placebo treatment for 52 weeks. The results will hopefully be available in 2021 (click here to read more about this study).

The different forms of Vitamin B3. Source: Longecity

The different forms of Vitamin B3. Source: Longecity

Another Silverstein Foundation supported company that may give us interesting news this year is resTORbio.

This is a biotech company developing selective inhibitors for TORC1.

This is a biotech company developing selective inhibitors for TORC1.

mTOR is a protein that forms two protein complexes (combination of proteins bound together) to perform its function. These two complexes are known as TORC1 and TORC2.

TORC1 and TORC2. Source: dev.biologists

TORC1 and TORC2. Source: dev.biologists

Importantly, TORC1 inhibition is associated with lots of good things, such as prolonging lifespan, enhance immune function, enhancing memory, and delaying the onset of age-related conditions in multiple animal models (Click here for a review of this topic). Meanwhile, TORC2 inhibition has been associated with lots of bad stuff (eg. decreased lifespan, worsening memory, etc – Click here for more on this). Thus, the biotech firm resTORbio is trying to inhibit TORC1, without inhibiting TORC2. And their lead drug candidate, RTB101 – a selective, orally-administered TORC1 inhibitor – is currently being tested in a Phase IIb clinical trial for reducing the incidence of respiratory tract infections (Click here to find out more about that trial). We will be looking for news from this company regarding Parkinson’s research/trial in 2019.

We will also be hoping for news from a biotech company called Intra-Cellular Therapies.

After presenting interesting results of a Phase I/II clinical trial of their phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitor ITI-214 (Click here to read more about this), we will be looking to see the initiation of a much larger study in 2019. Researchers are scheduled to present data at the Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s 2019 meeting in March, perhaps we will learn more at that time.

After presenting interesting results of a Phase I/II clinical trial of their phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitor ITI-214 (Click here to read more about this), we will be looking to see the initiation of a much larger study in 2019. Researchers are scheduled to present data at the Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s 2019 meeting in March, perhaps we will learn more at that time.

And finally, there are studies that are not expected to report until 2020, but we may also hear some news from them before then if we are lucky.

For example, a clinical trial of a product derived from young blood plasma (called GRF6021) has recently been initiated by a biotech firm named Alkahest. At the end of 2018, the company announced that they have dosed the first participant in a Phase II clinical trial of their product GRF6021 in people with Parkinson’s and cognitive impairments (Click here for the press release and click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). This study is being supported by the Michael J Fox Foundation.

At the end of 2018, the company announced that they have dosed the first participant in a Phase II clinical trial of their product GRF6021 in people with Parkinson’s and cognitive impairments (Click here for the press release and click here to read a SoPD post on this topic). This study is being supported by the Michael J Fox Foundation.

GRF6021 is a ‘plasma fraction’ (evidently made up of approximately 400 proteins derived from young blood – source).

The study is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II study in 90 people with Parkinson’s and cognitive impairment. It will be assessing the safety and tolerability of GRF6021 over a period of 7 months. The treatment (or placebo) will be administered by intravenous infusion for 5 consecutive days at Week 1 and Week 13 of the study (Click here to read more about the details of this clinical study). This trial will hopefully be finished in November 2019, so maybe we’ll hear something, but more likely we can expect to see the results in early 2020.

Whew!

Still reading? This is like a test of madness.

And it is honestly starting to feel like the post that will never end!

Onwards:

Above are just some of the neuroprotective clinical trials that are currently being initiated/conducted. I apologise for the ones that I have left out, but I am focusing on those starting or completing in 2019. If you are conducting a neuroprotective clinical trial in Parkinson’s and you would like a mention, by all means contact me.

And now, we move on to 2019 clinical trials involving:

3. Some form of cell replacement therapy

Once the condition has been slowed/halted (#1) and a neuroprotective/nurturing environment is in place to protect the remaining cells (#2), a curative treatment for Parkinson’s will require replacing some of the cells that have been lost.

By the time a person is presenting the motor features characteristic of Parkinson’s, and being referred to a neurologist for diagnosis, they have already lost approximately 50% of the dopamine producing neurons in an area of the brain called the midbrain. These cells are critical for normal motor function – without them, movement becomes very inhibited.

And until we have developed methods that can identify Parkinson’s long before the motor features appear (which would require only a disease halting treatment), some form of cell replacement therapy is required to introduce new cells to take up lost function.

Cell transplantation represents the most straight forward method of cell replacement therapy.

Traditionally, the cell transplantation procedure for Parkinson’s has involved multiple injections of developing dopamine neurons being made into an area of the brain called the putamen (which is where much of the dopamine naturally produced in the brain is actually released). These multiple sites allow for the transplanted cells to produce dopamine in the entire extent of the putamen. And ideally, the cells should remain localised to the putamen, so that they are not producing dopamine in areas of the brain where it is not desired (possibly leading to side effects).

Targeting transplants into the putamen. Source: Intechopen

Postmortem analysis – of the brains of individuals who have previously received transplants of dopamine neurons and then subsequently died from natural causes – has revealed that the transplanted cells can survive the surgical procedure and integrate into the host brain. In the image below, you can see rich brown areas of the putamen in panel A. These brown areas are the dopamine producing cells (stained in brown). A magnified image of individual dopamine producing neurons can be seen in panel B:

Transplanted dopamine neurons. Source: Sciencedirect

The transplanted cells take several years to develop into mature neurons after the transplantation surgery. This means that the actually benefits of the transplantation technique will not be apparent for some time (2-3 years on average). Once mature, however, it has also been demonstrated (using brain imaging techniques) that these transplanted cells can produce dopamine. As you can see in the images below, there is less dopamine being processed (indicated in red) in the putamen of the Parkinsonian brain on the left than the brain on the right (several years after bi-lateral – both sides of the brain – transplants):

Brain imaging of dopamine processing before and after transplantation. Source: NIH

The old fashioned approach to cell transplantation involved dissecting out the region of the developing dopamine neurons from multiple donor embryos, breaking up the tissue into small pieces that could be passed through a tiny syringe, and then injecting those cells into the brain of a person with Parkinson’s.

The people receiving this sort of transplant would require ‘immunosuppression treatment’ for long periods of time after the surgery. This additional treatment involves taking drugs that suppress the immune system’s ability to defend the body from foreign agents. This step is necessary, however, in order to stop the body’s immune system from attacking the transplanted cells (which would not be considered ‘self’ by the immune system), allowing those cells to have time to mature, integrate into the brain and produce dopamine.

There is currently a European clinical trial currently ongoing called Transeuro that is using this procedure to test this approach.

The Transeuro trial. Source: Transeuro

The Transeuro trial. Source: Transeuro

This trial is an open label study, involving 13 subjects, transplanted in different sites across Europe.

In addition to the Transeuro study, there are currently 3 ongoing stem cell-based clinical trials for Parkinson’s.

The first of those clinical trials is being conducted in Melbourne (Australia), by an American company called International Stem Cell Corporation (ISCO).

This study is taking the new approach to cell transplantation, and the company is using a different type of stem cell to produce dopamine neurons for transplantion in the Parkinsonian brain.

Specifically, the researchers will be transplanting human parthenogenetic stem cells-derived neural stem cells (hpNSC). These hpNSCs come from an unfertilized egg – that is to say, no sperm cell is involved. The female egg cell is chemically encouraged to start dividing and then it becoming a collection of cells that is called a blastocyst, which ultimately go on to contain embryonic stem cell-like cells.

The process of attaining embryonic stem cells. Source: Howstuffworks

This process is called ‘Parthenogenesis’, and it’s not actually as crazy as it sounds as it occurs naturally in some plants and animals (Click here to read more about this). Proponents of the parthenogenic approach suggest that this is a more ethical way of generating embryonic cells as it does not result in the destruction of a viable organism. The stem cells derived from this process can be grown into neuronal cells before being transplanted into brain.

Long time readers of this blog will be aware that I am extremely concerned about this particular trial (Click here and here to read previous posts about this). I will hold my tongue here, but we are expecting the results of the ISCO Phase I clinical trial in early 2019 – expect an SoPD post on this topic when those results are released.

In 2018, a second stem cell-based cell transplantation clinical trial was initiated by a research group from China led by Professor Qi Zhou, a stem-cell specialist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Zoology.

The clinical trial (Titled: A Phase I/II, Open-Label Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of Striatum Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells-derived Neural Precursor Cells in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease) will take place at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University in Henan province.

The researchers are planning to inject neuronal-precursor cells derived from embryonic stem cell into the brains of individuals with Parkinson’s. They have 10 subjects that they have found to be well matched to the cells that they will be injecting, which will help to limit the chance of the cells being rejected by the body.

This trial will be a single group, non-randomized analysis of the safety and efficacy of the cells. We have had very little information about this study, but the estimated date of completion is December 2020 (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic).

And the third on-going stem cell-based cell transplantation clinical trial is the ‘induced pluripotent stem’ (or IPS) cell study being conducted in Kyoto, Japan.

This ongoing cell transplantation trial is being conducted by researchers at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (or CiRA).

This ongoing cell transplantation trial is being conducted by researchers at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (or CiRA).

Prof Jun Takahashi is leading a team that is using IPS cells for a clinical cell transplantation trial for Parkinson’s. In 2017, they published very impressive data using these cells in primate models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about that research report).

Prof Jun Takahashi is leading a team that is using IPS cells for a clinical cell transplantation trial for Parkinson’s. In 2017, they published very impressive data using these cells in primate models of Parkinson’s (Click here to read more about that research report).

Prof Jun Takahashi (speaking) and colleagues. Source: Japantimes

Prof Jun Takahashi (speaking) and colleagues. Source: Japantimes

Information provided by Kyoto University (Click here for the study website) and the Japanese media has indicated that this Phase I/II clinical trial aims to investigate the safety and efficacy of transplanting human IPS cell-derived dopaminergic progenitors into the brains of people with Parkinson’s (what stage of PD has not been disclosed). The study will involve just 7 participants, who are all Japanese individuals with Parkinson’s. The participants in the study will be followed and assessed for 2 years post transplantation (Click here to read a previous SoPD post on this topic). I am not entirely sure when we will be learning the results of this study (anybody else know?).

In addition to these 4 ongoing cell transplantation clinical trials, in 2019 – in fact in the first couple of months of this year – we are hoping to see a press release announcing the commencement of a US-based clinical study for stem cell-based cell transplantation in Parkinson’s being conducted by a biotech company called BlueRock Therapeutics.

In December 2016, pharmaceutical company Bayer and healthcare investment firm Versant Ventures joined forces to invest $225 million in stem-cell therapy company BlueRock Therapeutics. This venture will be focused on induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived therapeutics for cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Parkinson’s (co-founders Lorenz Studer and Viviane Tabar are world renowned experts in the field of cell transplantation for Parkinson’s).

Prof Lorenz Studer. Source: Tmrwedition

Prof Lorenz Studer. Source: Tmrwedition

They submitting an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA in 2018, and have been waiting for approval to start clinical trials in late 2018 for the transplantation of dopamine neurons derived from embryonic stem cells (when I spoke with Prof Studer at the Parkinson’s UK research meeting in York in November, the company was still waiting for the green light).

The trial (called STEM-PD) will be an open label (meaning everyone will be aware of the treatment being administered) Phase I/IIa safety and tolerability study involving 10 individuals with moderate to severe Parkinson’s (5-10 years since diagnosis). Secondary aims of the study will be focused on the survival of the transplanted cells (as measured by brain imaging) and signs of efficacy (UPDRS part III motor score).

The surgery will be a single session, with 3 injections of cells being made on each side of the brain. Each of the 3 injections of cells will involve 3 deposits at different sites along the injection track in the putamen. Two doses of cells will be evaluated in the study – a low dose (0.9 million cells per side of the brain, which should result in 100,000 surviving cells) and a high dose (2.7 million cells per side of the brain, which should result in 300,000 surviving cells).

And all of the participants will be on immunosuppression medication for 12 months to insure that the cells have the best chance of survival (without immunosuppression there is the chance that the immune system will view the transplanted cells as foreign and kill them). Fingers crossed that the study be allowed to begin soon.